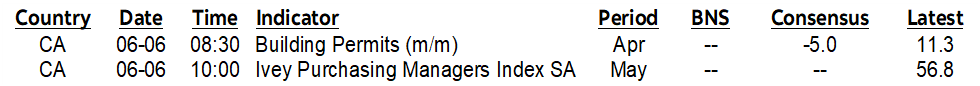

ON DECK FOR TUESDAY, JUNE 6

KEY POINTS:

- RBA surprises consensus and markets for a second time

- Similarities and differences between the RBA and BoC

- Why the BoC should act now

- China’s moral suasion reduces risk of PBoC easing

- Oil prices took one day to reverse the OPEC+ effects

- ECB consumer survey lowers still-high inflation expectations

- No material releases on tap in N.A.

That not all central banks are done hiking rates was made clear by another surprise hike by the RBA. A balanced comparison between their situation and the BoC’s is offered below.

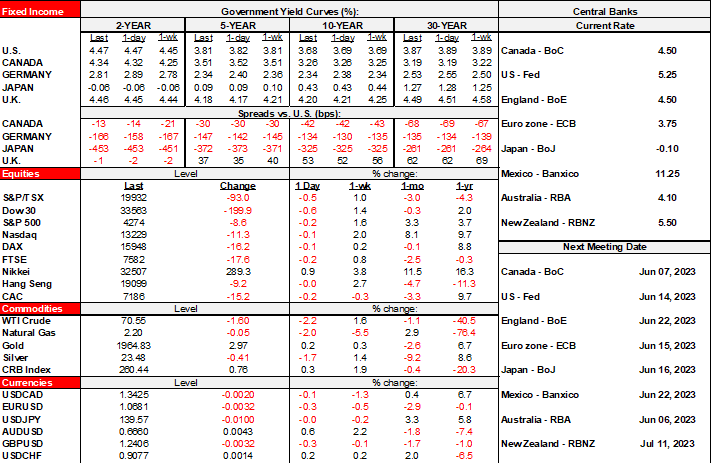

Global developments are otherwise relatively light. Chinese authorities are using moral suasion powers against state-owned banks to engineer deposit rate cuts that likely serve as a substitute for cutting the main policy rate next week. Oil prices have rapidly shaken off yesterday’s effects following OPEC+ decisions with benchmarks down by over 2% and with WTI lower than it was at Friday’s close. An ECB survey pointed toward lower consumers’ inflation expectations with the one-year ahead measure down to 4.1% from 5% and the 3-year measure down to 2.5% from 2.9%. Overall risk appetite across asset classes is a touch softer. NA equity futures are flat to a pinch lower and European cash markets are slightly lower. With the exception of Antipodean curves, sovereign debt yields are slightly lower across US Ts, gilts and somewhat more so across EGBs and these moves started before the ECB’s survey and were partially driven by the other cited influences. Canada’s rates curve is slightly underperforming US Ts with a full hike priced for July and about half of one priced for tomorrow. The A$, C$, and MXN are leading currency gainers to the USD.

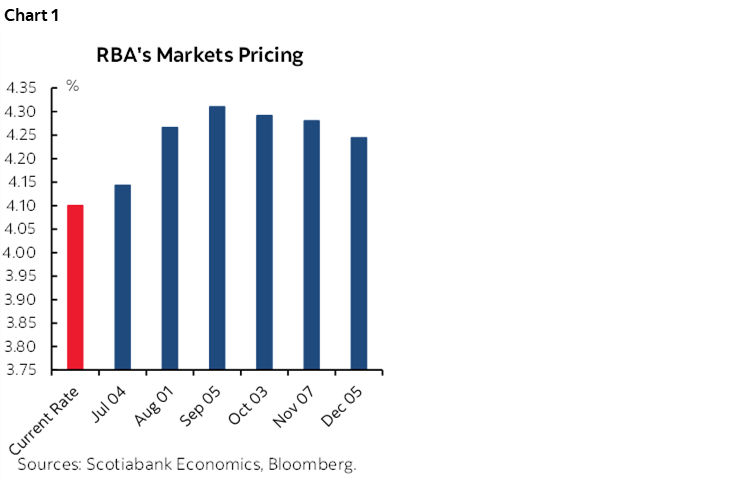

The RBA surprised consensus and markets for a second time in a row by hiking its cash rate target by 25bps to 4.1% overnight. Just as only 9 of 30 forecast a hike in May, only 10 of 30 did so today and markets were underpriced for the risk. This is a further demonstration of the fact that central banks don’t necessarily care one iota what consensus or markets expect and craft policy to their liking. The RBA also repeated guidance that “Some further tightening of monetary policy may be required to ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe, but that will depend upon how the economy and inflation evolve.” The A$ appreciated by just under half a cent to the USD. Australia’s curve bear flattened with the 2-year yield jumping by 9bps post-decision. Futures are pricing most of another quarter-point hike by September with smaller fractions of a hike priced for the July and August meetings (chart 1).

THE RBA VERSUS THE BoC—SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

There are significant differences alongside striking parallels to the BoC’s situation based upon drawing comparisons between the RBA’s reasoning for its tightening (statement here) and the Canadian situation. Here they are.

1. There is one argument for a relatively more hawkish RBA than the BoC. With an important caveat, the RBA faces higher inflation at a lower policy rate relative to its neutral rate than the BoC notwithstanding a higher RBA inflation target. Therefore, the RBA may have had more reason for back-to-back surprises in terms of magnitudes of the relative inflation challenge notwithstanding ongoing overshoots in both cases. Australian inflation ran at 6.8% y/y in April with core CPI matching the 6.8% headline rate and trimmed mean at 6.7%. Canadian inflation was 4.4% y/y in April with trimmed mean and weighted median CPI at 4.2% y/y and with both ‘core’ measures running at a four-handled m/m SAAR pace. The caveat is that some of this higher Australian inflation has to be weighed against the fact that the RBA has a higher inflation target of 3% versus the BoC’s 2% for a net overshoot of almost four percentage points in Australia right now versus around 2½% in Canada. The RBA’s policy rate of 4.1% is now getting closer to the BoC’s 4½ versus the RBA’s nominal neutral rate estimate of “at least” 2½% and the BoC’s 2½% estimate within a 2–3% band.

2. Both central banks are worried about being unable to get inflation down to target within their normal medium-term horizons. The BoC says the easy deceleration has been achieved but the next leg down to 2% will be harder and Macklem has signalled a determination toward doing so. The RBA said something similar as justification for pulling the trigger:

“This further increase in interest rates is to provide greater confidence that inflation will return to target within a reasonable timeframe.”

3. Both central banks are more worried about upside risks to inflation than downside risks. That’s clear in everything that BoC Governor Macklem has said for a while now and it was spelled out in the RBA’s statement here:

“Recent data indicate that the upside risks to the inflation outlook have increased and the Board has responded to this.”

4. Both countries have poor productivity growth and rising unit labour costs (productivity adjusted employment costs). Macklem has referenced this, and the RBA said it here:

“Unit labour costs are also rising briskly, with productivity growth remaining subdued.”

And

“At the aggregate level, wages growth is still consistent with the inflation target, provided that productivity growth picks up.”

5. Both countries are going through higher wage pressures in public sector collective bargaining agreements, and this could spill over into broader gains. The RBA said this:

“Growth in public sector wages is expected to pick up further and the annual increase in award wages was higher than it was last year.”

6. Both countries are seeing their housing markets come back to life and lift house prices. That’s apparent in another fresh round of Canadian data in the key Spring market. The RBA said this about the trade-off of effects on leverage households versus flagging overall housing market developments:

“Housing prices are rising again and some households have substantial savings buffers, although others are experiencing a painful squeeze on their finances.”

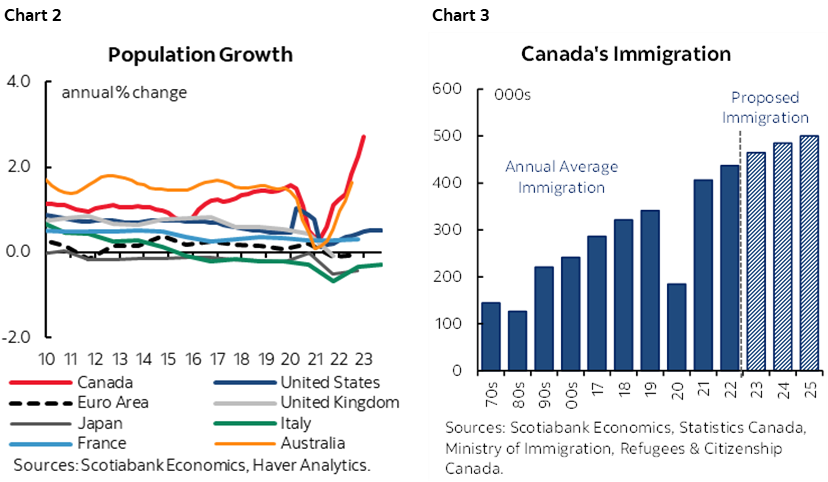

There are other differences between the two central banks that merit consideration. Australian immigration has recovered from the pandemic shocks but is marginally higher than pre-pandemic levels versus a lot higher in Canada with aggressive targets (charts 2, 3). This immigration surge in Canada affects demand for housing amid sticky housing supply that puts upward pressure upon house prices and related inflation and sorry folks but there’s no evidence that higher immigration depresses wage growth as some shops state rather divisively. Australia is more attached to China’s economic challenges and while the US faces challenges I’m more constructive on its consumers and the pull effect on Canadian exports with a depreciated currency than some others might be. On fiscal policy, Canadian provinces have more tax and spend powers and my oh my they are using them to spend more each year to reinforce ongoing federal fiscal stimulus.

Nevertheless, monetary policy is crafted not via international comparisons, but in accordance with domestic circumstances. For the BoC, why hike now instead of waiting? There is a rich case for doing so that has been elaborated upon in many notes and through client marketing that won’t be repeated here other than to make a few summary points on timing.

- They’ve already waited too long since prematurely pausing back in January which is the longest pause of any peer group central bank. Further delay would be undesirable since with each passing month’s persistence of inflationary pressures and housing imbalances the BoC risks losing control of extrapolative expectations on both counts including FOMO effects in housing. Multiple measures such as consumer and business inflation expectations and the resumption of rising house price expectations signal disbelief toward the BoC’s seriousness and it’s time to counter that.

- Macklem said they considered a hike in April. They were close then, and the case has since grown as GDP is materially beating the BoC’s expectations, core inflation m/m SAAR accelerated, job markets remain strong, the US debt ceiling issue is over with and US regional bank challenges have calmed down.

- Waiting until July will mean only one chance to hike 25bps until September and they are unlikely to go 50 imo. If they wanted more policy optionality around upside risks to inflation within a reasonable time horizon then going now would open it up for them. Otherwise, they’ll probably be boxed into one measly quarter point hike for June, July, August and into September.

- A whiff now could ease financial conditions through a rates rally and CAD depreciation when they don’t need to be eased. A whiff could effectively deliver a cut. I’m not sure that even being very explicit on the bias would offset this since markets may haircut possible hike guidance amid uncertainties between now and the July 12th decisions.

- Time is of the essence. They would completely miss the Spring/summer housing market and seasonal consumer purchases.

- It’s nonsense that they need an MPR. Macklem has given all the guidance they need to merit delivering a hike in multiple appearances and comments since the April presser through the IMF roundtable, two parliamentary committee testimonies and multiple media appearances.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.