Chile: BCCh Economic Expectations Survey’s 2021 real GDP forecast adjusted up; we maintain our 7.5% y/y projection

Mexico: Soft pace for job creation in March

Peru: Everything you wanted to know about the elections…except the final outcome

CHILE: BCCh ECONOMIC EXPECTATIONS SURVEY’S 2021 REAL GDP FORECAST ADJUSTED UP; WE MAINTAIN OUR 7.5% Y/Y PROJECTION

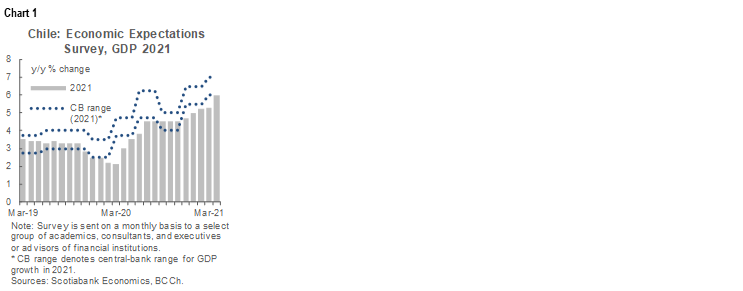

The BCCh published on Monday, April 12, its Economic Expectations Survey for April, which showed an improvement in the consensus forecast for 2021 real GDP growth from the March Survey’s 5.3% y/y to 6% y/y. This is in line with the adjustments made by the central bank in its March Monetary Policy Report where it raised its range of expected GDP growth from 5.5–6.5% y/y to 6–7% y/y, with an implicit projection of 6.8% for this year (chart 1).

We expect to see further upward adjustments in GDP expectations by economists surveyed by the central bank in the coming months. The Survey’s consensus forecast now sits at the same rate that we projected one month ago. In March, we updated our economic outlook to feature forecasts of 7.5% y/y growth for 2021 and 3.5% y/y for 2022.

Despite the recent increase in COVID-19 cases and the new lockdown measures that are affecting about 90% of GDP in some way or another, our baseline forecast of a 7.5% y/y expansion in Chile’s real GDP in 2021 remains solid. It takes account of an estimated -4% m/m sa contraction in March owing to new public-health measures, which would still leave activity up between 2% y/y and 4% y/y in the month. Note that this forecast is dependent on the duration of the confinement measures. For now, we expect that mobility restrictions will start to be gradually lifted in May.

—Carlos Muñoz & Waldo Riveras

MEXICO: SOFT PACE FOR JOB CREATION IN MARCH

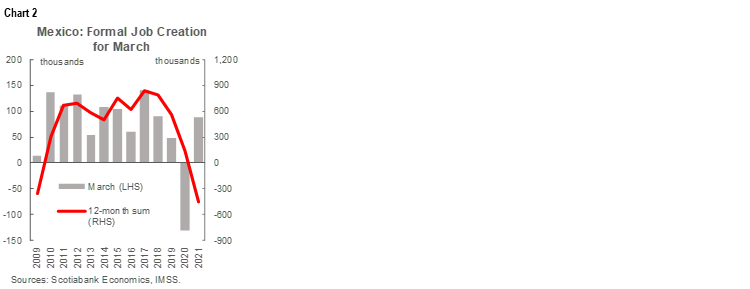

According to data released by the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) on the afternoon of April 12, formal job creation moderated from 115.3k in February to 88.8k in March (chart 2). This was equivalent to 0.4% monthly growth. Formal jobs totaled 20.025 mn, of which 85.6% were permanent jobs and the remaining 14.4% were temporary positions. Thus, during Q1-2021, some 252k jobs were created, of which only 54.5% represented new permanent posts. Gains were focused in three out of nine sectors: processing (1.3% m/m), electricity (0.02% m/m), and social and community services (0.02% m/m). However, on an annual basis, the gap in total formal jobs compared with the pre-pandemic period improved from -3.3% y/y to -2.2% y/y, but was still in negative territory.

The number of formal employers affiliated to the Institute (1,002,537) increased by 1,627 businesses. The rise in the number of employers participating in the social-security system could have benefited from softer COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the state-level epidemiological traffic-light framework, allowing the re-opening of some businesses. However, in an annual comparison, the number of IMSS-affiliated employers edged back for a sixth consecutive month, going from -0.4% y/y to -0.5% y/y.

Lastly, the average salary of formal workers rose in nominal terms by 7.1% y/y in March, down from the previous 8.1% y/y. This was equivalent to MXN 427 per day (approx. USD 21). Nominal salaries have gone up persistently by more than 6.0% y/y since January 2019.

Going forward, as we approach the summer it will be relevant to track what, if any, change the national government’s expected restrictions on the use of outsourcing will have on formal job creation. Today, about 20% of employment operates under the current outsourcing regime, which is set to be severely restricted to non-core activities.

—Miguel Saldaña

PERU: EVERYTHING YOU WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT THE ELECTIONS…EXCEPT THE FINAL OUTCOME

At the time of writing (night of Monday, April 12), about 85% of votes had been counted, and the first-round outcome had been all but determined. The most likely scenario is that Pedro Castillo (Perú Libre) and Keiko Fujimori (Fuerza Popular) will be facing each other in a second-round runoff in June. Castillo has secured 18.8% of valid votes counted at this point. Fujimori is running second with 13.2%. She has a lead of only 1.2 ppts over Hernando de Soto (Avanza País, 12.0%), but the trend is in her favour. Rafael López Aliaga (Renovación Popular) is in fourth with 11.9% of votes counted and Yonhy Lescano (Acción Popular) is in a rather distant fifth at 9.1%.

In these extraordinary elections, the first two candidates are garnering, between them, no more than a third of total votes cast and counted. This means that two-thirds of the population will not have voted for the two candidates that make it into the second round. In fact, one would need to add together the four leading candidates to surpass 50% of total votes. This won’t provide much of a mandate for whoever wins. And it also raises the question of how the other two-thirds of the population will vote in the second round of presidential elections on June 6 considering that it is composed of very different segments of society with varying mindsets.

The elections have reminded us just how divided the country is. There are, perhaps, four main camps. Depending on how one defines who is who among the 18 candidates, a back-of-the-envelope calculation might be: the left with about 25% of votes, the right with 20%, centre with 20%, and populists with 20%, with the rest scattered and fluid in their support. Another division in the electorate pits Lima versus the interior, and, within the interior, rural versus urban areas. Lima tended to vote more right of centre, rural areas more left of centre, and non-Lima urban areas more centre-populist.

Castillo is this election’s great outsider: it would appear that in Peru, every election needs one. Five weeks ago Castillo was treading water with only 4% of voting intentions. This may have worked in his favour. While everyone else was busy attacking their perceived rivals, he was ignored. In the end he took votes from both Lescano and Verónika Mendoza, especially in rural areas. But, note that his surge was actually a mild one when compared with past elections. His roughly 19% of valid votes should mean under 15% of total votes cast—which in turn would mean that 85% of the country did not vote for him. Also, luck favoured him in terms of timing. In an election with soft voting intentions across the board, the lead changed hands a number times in the past two months. The elections occurred when support for Castillo just happened to have been cresting.

The second round is likely to be polarized as both Castillo and Keiko are controversial figures. Both have negative voting biases playing against them, but they are the only choices left. The second round of elections tends to look nothing like the first, so it’s not easy to draw any conclusions before the first polls on the head-to-head contest are released. However, Keiko would probably have a better chance of winning against Castillo than Hernando de Soto or López Aliaga would, as the latter two are closely identified with Lima, whereas Keiko bridges the Lima-interior voting gap.

Keiko sent a very significant message on Sunday night: she suggested that she would endorse de Soto if he makes it to the second round and, in turn, asked de Soto to endorse her if she’s the lucky one to get through. She appears to be preparing a second-round platform based on the idea of a united front against radical change.

Pedro Castillo is a teacher and a union leader. He organized massive protests by the education labour union (Sutep) in 2017. The actual leader of the Perú Libre party, however, is Vladimir Cerrón, a doctor who studied medicine in Cuba. Castillo is more the activist, Cerrón is more the ideologue, in Perú Libre. Cerrón is the author of the party’s platform, for instance, but he was prevented from running because he had been sentenced for malfeasance when he was governor of Junín.

Peru Libre (PL) defines itself as a socialist organization that embraces Marxist-Leninist theory. It is calling for a new constitution. It is anti-establishment and is likely to challenge Peru’s institutional framework. Looking at its agenda, one wonders if PL has any sense of budgetary constraints. This is a party, and leadership, that appears distrustful of the private sector, of foreign companies, and of anything come out of Lima—and seems intent on reducing the frontiers for all three. PL believes in greater State activity in strategic economic activities, and could tinker with anything from mining to transportation infrastructure, from Peru’s free trade agreements to the pension fund system. A PL cabinet is likely to consist of a close circle of individuals that share the party’s mindset.

In principle, however, there would be severe limits on what a PL government could do. Castillo is being compared with Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales, but he does not have the military support that Chávez had, nor the popular support that either Chávez or Morales had when they came into office. A PL government will not have control of Congress, the army, the judicial system, or regional governments. The risk, however, is that there could be a continual environment of tension and conflict as the PL challenges the country’s institutions. On the other hand, Cerrón has been a governor, and he largely behaved within the country’s legal and institutional framework during his time in office. Also, note that the PL’s platform does make room for private enterprise as something to be fostered and “protected”, albeit within a nationalistic, closed-economy, perspective.

Keiko Fujimori is clearly better known and prepared for office. The key to success for a possible Fujimori government could reside in the extent to which Fuerza Popular (FP) tries, and succeeds, in broadening its base and appeal. Fujimori is very aware of the anti-Keiko sentiment that she will face and she has been trying to transmit a message of reconciliation for some time. She will need to prove her sincerity quickly. If she does, she could conceivably make alliances with parties on the right in Congress, at least to the extent of blocking, say, any initiative that might emerge to impeach her—something which, of course, has become very popular on Peru’s political scene of late. A Fujimori government would be likely, we believe, to seek good relations with the private sector, and it would also be able to attract talent to the cabinet. The FP’s platform is quite elaborate: it is not improvised, it is even footnoted, with cross references to publications

Finally, Congress: as many as eleven parties may have received enough votes to be awarded seats. The final tally will vary, but a rough estimate might have PL (Castillo) with just under 30 of the 132 congressional seats. The left as a whole could have maybe 35–40 seats, not enough for a majority. The right might have 30 seats, but could join with the centre, to reach perhaps 40 to 45 votes (including Keiko’s Fuerza Popular). Then there are the outright populists, with 20 seats, which may ally with the left on certain issues. On the face of it, the new Congress looks to be mildly less populist than the current edition. Two populist parties, UPP and Frepap, will no longer be in Congress. In their stead will be centre-right parties such as Avanza País, Victoria Nacional, and (possibly) Renovación Popular. Plus, some of the parties that had been leaning populist in the current Congress, such as Acción Popular and Fuerza Popular, appear to be geared to standing a bit straighter in the new assembly.

—Guillermo Arbe

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.