Central banks & macro data: Minutes and Monetary Policy Report from Colombia’s BanRep; January inflation in Peru and Colombia, Chile’s December GDP proxy

Chile: Employment recovery slows down as labour-market participation still depressed

Colombia: BanRep held at 1.75% as new macro forecasts arrive; seventy-five percent of pandemic-related job losses reversed by end-2020

Mexico: Preliminary estimates for Q4-2020 GDP; financing to the private sector registered a record annual contraction in December

Peru: The meaning of the new containment measures

CENTRAL BANKS & MACRO DATA: MINUTES AND MONETARY POLICY REPORT FROM COLOMBIA’S BANREP; JANUARY INFLATION IN PERU AND COLOMBIA, CHILE’S DECEMBER GDP PROXY

I. Central banks

Colombia’s BanRep publishes at 17:00 EST today the minutes of its Friday, January 29, monetary-policy meeting. It also publishes today its first Monetary Policy Report under the direction of new Governor Leonardo Villar. The usual presentation and press conference on the report are planned for Wednesday, February 3.

II. Macro data

- Chile. December’s IMACEC monthly GDP proxy grew by 3.5% m/m sa, up from 1.1% m/m in November. Owing to level effects following the October 2019 social unrest, this still pulled down annual growth from 0.3% y/y in November to -0.4% y/y in December—yet well above the -2.3% y/y Bloomberg consensus. The print bested our estimate of 1% m/m sa which reflected December’s enhanced restrictions on mobility.

- Colombia. January inflation numbers are due at 19:00 EST on Friday, February 5. Our team in Bogota expects inflation to soften from 0.4% m/m in December to 0.3% m/m, while consensus expects 0.4% m/m. Our estimate implies annual inflation of 1.5% y/y, down from 1.6% y/y, while consensus expects 1.6% y/y. Annual adjustments and food prices would have led the month’s inflationary pressures.

- Mexico.

- December remittances inflows, scheduled for publication at 07:00 EST on Tuesday, February 2, should notch up another record month around USD 3.4 bn.

- November gross fixed investment numbers are due to be published at 07:00 EST on Friday, February 5. With October investment numbers down -14.7% y/y, the annual gap likely narrowed further in November owing to some easing in public-health restrictions and favourable financial conditions.

- Peru. January’s Lima inflation reading, released at 10:00 EST this morning, came in at 0.74% m/m sa, up from 0.05% m/m sa in December and well above the Bloomberg consensus of 0.11% m/m sa. We had been tracking a print of around 0.4% m/m sa based on data available by last week. This took annual inflation up from 1.97% y/y in December to 2.68% y/y in January, and implies upside risk to our 2% y/y forecast for all of 2021.

—Brett House

CHILE: EMPLOYMENT RECOVERY SLOWS DOWN AS LABOUR-MARKET PARTICIPATION STILL DEPRESSED

I. Sectoral figures: Heterogeneity continues, with a boom in private consumption triggered by pension withdrawals

On Friday, January 29, sectoral and employment data for December were released by the INE.

Retail trade disappointed us: although it recorded a notable annual expansion at 10.4% y/y in December this was lower than our forecast of 18% y/y. The product lines that contributed the most to rise in retail activity were electronic products, food, and construction materials. Car sales have shown a relevant recovery thanks to the greater liquidity available to households as a result of pension asset withdrawals: the INE reported only a moderate drop of -6% y/y in car sales for the last month of 2020. In any case, rather than the surveys employed by the INE, the central bank uses information more similar to ours (i.e., data on effective purchases). Consequently, we expect the BCCh to incorporate in its modelling stronger commercial activity for December than indicated by the INE’s numbers.

Manufacturing production showed a weak advance in December, expanding 0.4% y/y, slightly below our projection of 2.0% y/y. The re-imposition of quarantines in the face of increased COVID-19 infections likely weighted on the sector’s performance. By division, the production of food products showed the highest annual growth owing to greater production of dairy products in response to increased national demand. On the other hand, the manufacture of chemical products showed the weakest results, which reflected lower external demand.

Mining production showed a marked decline of -9.3% y/y after two months of year-on-year advances. All of mining’s sub-sectors recorded annual declines in December. Metallic mining was down owing to reduced extraction and processing of copper, which partially reflected lower mineral grades in the raw material handled by key companies in the sector. The sector’s weakness in December also resulted from some transitory factors linked to stoppages in relevant tasks.

II. Labour market: job recovery continues, but at a clearly slower pace

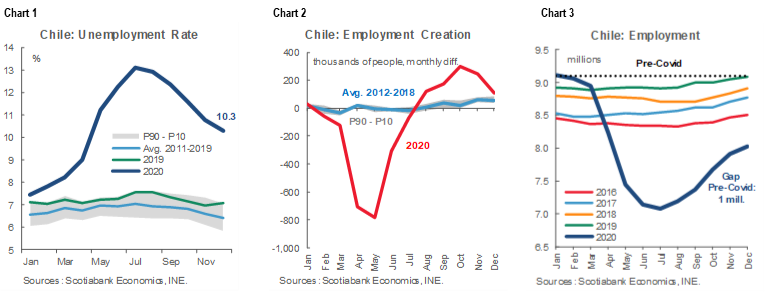

Chile’s national unemployment rate decreased again from 10.8% in the moving quarter September–November to 10.3% in October–December 2020 (chart 1). The reduction reflected greater dynamism in employment growth compared with labour-force participation despite December’s retreat toward tighter mobility restrictions. This should reverse in the coming months as job search increases, which should keep the unemployment rate at high levels for much of 2021. Despite the fact that employment continues to recover (chart 2), its pace slowed in the last months of 2020 and about 1 mn jobs lost due to the pandemic still need to be recovered (chart 3). According to INE estimates, the potential unemployment rate (i.e., which includes potentially active workers) is currently at 21.6%.

Job creation continued to slow in December with a gain of only 109.5 thousand jobs compared to the previous moving quarter. At this rate of recovery, Chile won’t return to pre-pandemic employment levels until 2022. The sectors that continue to lead job creation include commerce, construction, and some seasonal sectors. In other sectors, especially services, the recovery in employment remains very slow.

—Jorge Selaive, Carlos Muñoz, & Waldo Riveras

COLOMBIA: BANREP HELD AT 1.75% AS NEW MACRO FORECASTS ARRIVE; SEVENTY-FIVE PERCENT OF PANDEMIC-RELATED JOB LOSSES REVERSED BY END-2020

I. BanRep Board held its benchmark monetary policy rate at 1.75% again in a split vote as the new Governor underscored that the current stance is expansionary

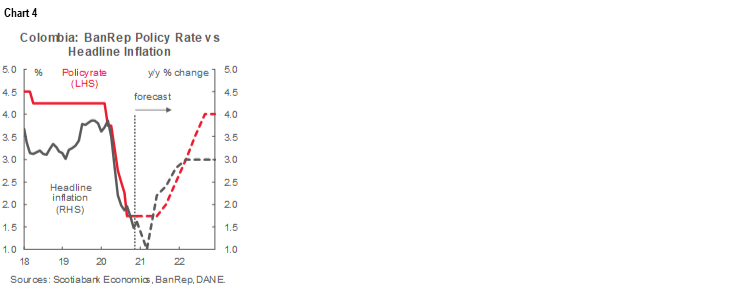

On Friday, January 29, the BanRep Board left the monetary policy rate (MPR) at 1.75% as expected by both ourselves and market consensus—again in a split vote, five versus two (chart 4). New Governor Leonardo Villar underscored in the press conference following the meeting that the Bank’s monetary-policy stance remains expansive and continues to support the economic recovery.

In the communiqué, the Board emphasized that Colombia’s economic recovery is expected to continue in 2021. The Board additionally noted that the financial system remains in favourable condition and that loan dynamics have reacted in a positive way to previous cuts in the monetary-policy rate.

The press conference’s tone was broadly neutral and featured three key messages: (1) the Board views the current MPR level as expansionary and that it should continue supporting the economic recovery; (2) despite the fact that inflation is currently low, it will be even lower in Q1, but after that it is expected to start progressing along a convergence path to the 3% target; and (3) the Bank’s estimate of the real neutral rate in 2021—calculated by the BanRep staff to be 1.5%—hasn’t changed. That said, Gov. Villar recalled the neutral language former Governor J. Uribe used by emphasizing that the Board will continue to evaluate incoming information in future decisions, especially data on the evolution of the pandemic, as it adjusts monetary policy to support Colombia’s economy.

Regarding the staff’s new macro scenario:

- Gov. Villar didn’t anticipate much about the new economic projections, but he did indicate that the recovery will continue and that the labour market remains a concern. Additionally, he reiterated that the Bank’s estimate of the neutral real policy rate hasn’t changed as he underscored that current rates are very expansionary; and

- The central bank staff will release the Monetary Policy Report today, February 1, and a press conference is scheduled for Wednesday, February 3. This publication will be essential to anticipate potential scenarios that could trigger future rate hikes, as well as their possible timing.

All in all, the BanRep’s decision met market expectations, and despite the split vote, the guidance was conservative, highlighting that the economic recovery is expected to continue, but the Board remains vigilant with respect to risks. We believe the Board’s inflation guidance is positive since it anticipates that a potential near-term reduction in price readings wouldn’t lead to further rate cuts. The maintenance of the existing estimate of the neutral real rate is essential to the Board’s review that its current stance is expansionary.

We maintain our call that the BanRep will remain on hold over the coming months with the possibility of a first rate hike in Q3-2021 (chart 4 again; see the January 25 Latam Weekly). The lift-off in policy rates we anticipate later in 2021 would be predicated on further consolidation of the economic recovery with inflation rising closer to the 3% inflation target.

II. Seventy-five percent of pandemic-related job losses reversed by end-2020

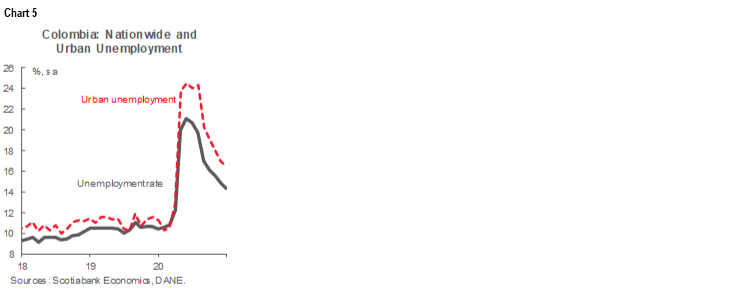

On Friday, January 29, DANE reported that in December, the nationwide unemployment rate came in at 13.4%, still well above December 2019’s 9.5% while the urban unemployment rate (i.e., for 13 major cities) came in at 15.6% versus 10.5% in December 2019. The seasonally adjusted series showed that the national unemployment rate improved to 14.3% versus 14.8% in November 2020, while the urban unemployment rate came down from 16.9% in November to 16.4% in December (chart 5). In all, the 2020 nationwide average unemployment rate was 15.9%, while the average urban rate was 18.2%—both significant deteriorations from 2019’s 10.5% and 11.2%, respectively.

By the end of 2020, the economy broadly consolidated activity under the “new normal” re-opening scheme with only a few activities restricted despite the recent surge in COVID-19 cases. In fact, we estimate that 96% of the economy was open by the end of last year and that in December around 75% of people, in net terms, who lost their job in the early stages of the pandemic were working again. Monthly job gains have recently been more moderate than in the initial stages of the re-opening. This could pose challenges for additional recovery in jobs since some sectors, such as manufacturing, are already operating at levels similar to those of the pre-pandemic era, but with less employment.

The quality of jobs remains an important issue of concern. Growth in formal jobs continued to lag the overall recovery (chart 6). We attribute these dynamics to the informal economy’s relative flexibility. Indeed, informality in urban areas increased by 1.5 ppts to 49.5% in 2020 compared with 2019. In 2021, improvements to both the quantity and quality of jobs will be needed to ensure a more sustainable recovery.

Additionally, the gender gap has raised the overall unemployment rate. For women, the rate of unemployment deteriorated from 13.1% at end-2019 to 17.9% in December 2020, while the unemployment rate for men increased by a much smaller delta from 6.9% at end-2019 to 10.1% at end-2020. This discrepancy is expected to persist over the near term since home-schooling during the remainder of the pandemic is likely to stymie women’s efforts to find new jobs. These trends pose considerable challenges for public policies related to tax collection, benefits provision, and economic development since they deepen longstanding structural problems.

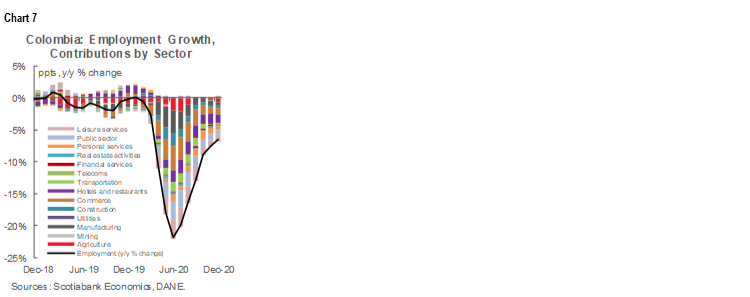

From a sectoral perspective, year-on-year employment losses as of December were concentrated in the leisure sector (-301k), hotels and restaurants (-277k), and commerce (-179k), which together accounted for 56% of the year-end’s total employment contraction (chart 7). However, a few sectors’ employment levels were similar to those observed one year ago, which pointed to some normalization in the economy. In 2020 the only sector which showed job gains were utilities (+33K), while telecoms (-24K), finance (-35K), and real estate (-47K) closed the year nearly unchanged.

All in all, the labour market ended 2020 on a marginally positive note despite the year’s considerable shocks from the pandemic as economic and job gains in December returned to pre-pandemic paces. This being said, hiring in January should slow down since regional anti-pandemic restrictions have raised uncertainty about the future. Going into February, we expect Colombia’s economic recovery to resume as the rate of contagion eases and governments could again begin withdrawing some restrictions. Boosting the recovery of formal employment is likely to remain the country’s biggest labour-market challenge.

—Sergio Olarte & Jackeline Piraján

MEXICO: PRELIMINARY ESTIMATES FOR Q4-2020 GDP; FINANCING TO THE PRIVATE SECTOR REGISTERED A RECORD ANNUAL CONTRACTION IN DECEMBER

I. Preliminary estimates for Q4-2020

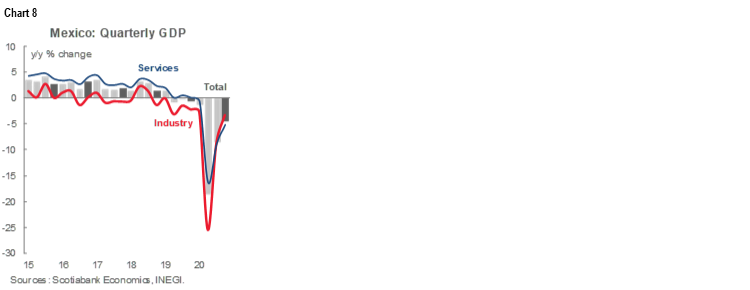

According to INEGI, the early estimate of Q4-2020 GDP, published on Friday, January 29, continued Mexico’s recovery at a better than expected, but softening pace. Growth slowed from 12.1% q/q sa in Q3 to 3.1% sa in Q4, versus a consensus expectation of 2.8% q/q. Sequential industrial growth slowed from 21.7% q/q in Q3 to 3.3% q/q in Q4; growth in services also ratcheted back from 8.8% q/q to 3.0% q/q.

This sequential slowdown narrowed the gap in economic activity compared with Q4-2019 from -8.6% y/y to -4.5% y/y (chart 8), which beat the market consensus of -5.6% y/y. Still, this marked a seventh consecutive month of declines compared with the same quarter a year prior. The Q4 preliminary numbers imply that the average real GDP growth rate during 2020 was -8.3% y/y, the largest calendar-year drop in real GDP since the current series began in 1994, but slightly below our prior estimate of -9.1% y/y (see the January 25 Latam Weekly). GDP has now contracted for two consecutive years for the first time since the 2001–02 period owing to the structural weaknesses the Mexican economy faced before the COVID-19 crises began.

The Q4-2020 annual decline in GDP reflected a seventh consecutive year-on-year pullback in industrial activity, though the sector’s annual gap narrowed from -8.8% y/y to -3.3% y/y (versus -2.2% y/y in Q4-2019, chart 8, again). Similarly, Q4-2020 marked the fourth consecutive annual decline in the services sector, where the gap likewise narrowed from -8.8% y/y in Q3-2020 to -5.1% y/y (versus 0.1% y/y a year earlier). The annual contractions in industrial and services activity were partially offset by gains in the agricultural sector, whose year-on-year growth rate also cooled, from 7.6% y/y to 4.8% y/y (versus -1.5% y/y in Q4-2019).

The early estimate of Q4-20202 GDP shows that, as production dynamics normalized in the second half of 2020, the economy observed a gradual improvement and moved through a slow recovery path. However, given the persistent weakness of gross fixed investment and private consumption, coupled with uncertainty regarding the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination efforts, we expect the recovery to moderate in 2021. The export sector is expected to lead further Mexican growth owing to the relatively stronger reactivation of the US economy.

—Miguel Saldaña

II. Financing to the private sector registered a record annual contraction in December

Bank lending data for December, released on Friday, January 29, by Banxico showed that financing to the private sector contracted to a record extent in annual terms. The year-on-year pullback stemmed from both marked weakness in consumer spending and sharp declines in business activity. At the same time, financing to the federal public sector continued to grow at unusually quick rates.

Looking at the details:

- Commercial bank financing to the private sector further accentuated its annual decline and went from -4.1% y/y in November to -4.4% y/y in December—its worst annual performance since records have been kept (chart 9). Direct financing also contracted from -4.2% y/y to -4.4% y/y. Within this segment, financing to companies recorded its largest-ever annual decline, from -4.0% y/y to -4.4% y/y, while consumer financing narrowed its annual gap from -11.3% y/y to -10.6% y/y. In the case of housing financing, it further retreated in real terms from -5.4% y/y in November to -5.8% y/y in December;

- On the other hand, financing to the federal public sector continued to grow significantly, with a 26.0% y/y real gain in December;

- Thus, total bank financing recorded a real annual increase of 2.5% y/y in 2020, up from 1.6% y/y a year earlier;

- On the other hand, annual growth in total commercial bank deposits from the non-bank public sector moderated its increase between November and December, going from 6.9% y/y to 6.6% y/y (chart 9, again), due to a slight moderation in growth in demand deposits, from 13.0% y/y to 12.5% y/y, while growth in fixed-term deposits contracted further, going from -2.5% y/y to -2.8% y/y;

- The scale of performing commercial bank credit to the private sector continued to contract in annual terms, going from -4.2% y/y in November to -4.6% y/y December, driven by a significant further contraction in credit to companies (from -4.1% y/y to -4.5% y/y) and to consumers (from -11.1% y/y to -11.5% y/y). This double-whammy is rare in December owing to all the seasonally spending that typically takes place in this month. In contrast, housing-oriented credit growth accelerated slightly from 4.9% y/y to 5.3% y/y, which may have reflected the benefit of relatively low interest rates; and

- Finally, the non-performing component of commercial bank loan portfolios kept expanding in the last quarter of the year. This was mainly driven by the consumer slice of these portfolios following the expiration of some financial institutions’ support programs that granted temporary relief to customers who had had difficulty paying their loans as a result of the pandemic.

—Paulina Villanueva

PERU: THE MEANING OF THE NEW CONTAINMENT MEASURES

The government provided, on Friday, January 29, more details on which economic activities will be allowed to operate between January 31 and February 14 under new COVID-19 containment measures. In a press release, the Office of the Cabinet stated that all agriculture, mining, fishing, energy, oil & gas, manufacturing and construction activities shall be allowed. These are in addition to services, including legal services, tourism, veterinarian services, medical services, accounting, architecture, and computer repair, among others, as well as those other services already defined as essential, such as market places, financial services, certain types of transportation, and even hospitality services (albeit under capacity restrictions). The full list can be found here.

Thus, the activities that are restricted are limited to those that imply a concentration of people where physical distancing is difficult, such as casinos, non-delivery restaurant services, education, sports clubs and gyms, and non-international travel.

Previously, the Head of the Cabinet, Violeta Bermúdez, had stated that the activities that would be allowed to operate would correspond to phase 2 of the 2020 de-locking of the economy, which accounted for 83% of the economy (chart 10). However, the current list goes beyond last year’s phase 2 and incorporates much of phase 3, under which 92% of the economy was allowed to operate. Given that the current restrictions apply only to the 10 regions under Extreme Alert, which account for 64% of the economy, while the remaining 36% of the economy in other areas will continue operating with 98% of activity open, we estimate that 95% of Peru’s total economic activities will be allowed to operate during the current new quarantine measures, versus 98% prior to the measures (chart 10, again).

What this all means is that major activities will continue to operate even in Extreme Alert regions. In particular, activities that have become drivers of growth, such as construction and public investment, will remain open for business.

We surmise from the mix of new measures that the government intends to restrict the mobility of people, but not the operations of businesses. Thus, the recent changes involve extending curfew hours, prohibiting the use of private vehicles, and closing or reducing capacity at places where people congregate, from casinos to churches.

Mobility restrictions will have an impact on growth, however, but it will mostly be through demand rather than supply. Some businesses may have issues with logistics and personnel, as transportation will be restricted and curfew hours extended. Private services by individuals and informal businesses may also have problems obtaining the travel passes they would need to continue operating smoothly.

On the up side, businesses have by now had time to adapt to circumstances that were even more stringent during the 2020 lockdown. There has been a structural change in favour of the digitalization of transactions that puts both companies and consumption more generally on different footings than they were a year ago.

The government has, so far, taken the following steps to support households and businesses. As we previously noted in the Thursday, January 28, Latam Daily, the government will provide a PEN 600 transfer to 4.2 mn households, for a total of PEN 2.5 bn in additional transfers. This sum will add to PEN 16.4 bn in flows linked to pension withdrawals that are already set to enter the economy in Q1-2021. In all, this amounts add up to the equivalent of nearly 2.7% of GDP. In addition, the government has indicated that it will provide a one-month deferment of income and sales tax payments for the Extreme Alert regions.

So, what will all this mean for GDP growth? It will depend on the duration of the measures, but the net impact should be less than we initially feared, given the limited effective nature of the “quarantine”. We are maintaining our forecast of 8.7% y/y GDP growth for 2021 for the time being (see the January 25 Latam Weekly). This means that we are foregoing the possibility we had been entertaining of revising our forecast upwards. If the new measures last only the 15 days currently envisioned, then we continue to see upside to our 8.7% y/y forecast. However, given the current COVID-19 trends, there is a real possibility that the measures will be extended in time. It seems prudent to wait and see if this comes about before revising our forecast.

—Guillermo Arbe

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.