- Colombia: Exports and employment edged back in April

- Mexico: Better than expected fiscal outturn to April; credit crunch intensified

- Peru: April business loan growth slowed; Fujimori pledge to uphold constitution

COLOMBIA: EXPORTS AND EMPLOYMENT EDGED BACK IN APRIL

I. April exports pulled back despite better commodity prices; nationwide strike likely to hit May numbers

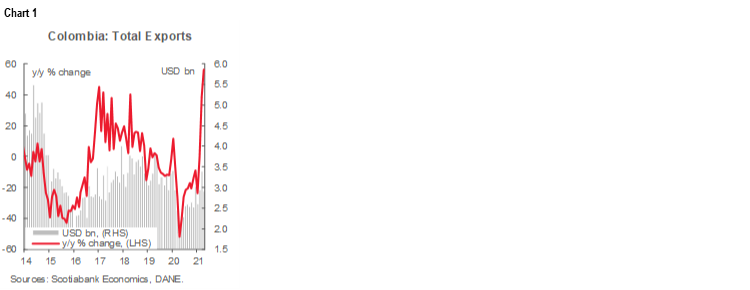

According to DANE’s release on Monday, May 31, April’s monthly exports stood at USD 2.91 bn (chart 1), up 56.3% y/y, but this growth rate was obviously skewed by the comparison with the early months of lockdown in 2020. Compared with the March figures, April’s exports were down by -14% m/m. Manufacturing exports were up by 58.1% y/y, while agricultural exports expanded by 24.5% y/y; oil & mining-related exports rebounded by 63.4% y/y, led by better oil prices rather than by volumes. Overall, export values still remain below pre-pandemic levels.

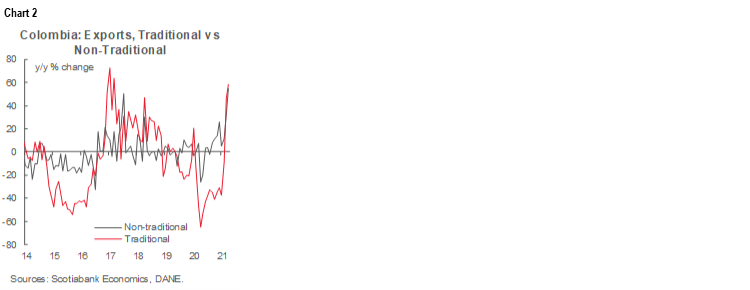

Traditional exports as a whole were up 58.3% y/y in April (chart 2) on the back of higher commodity prices. Oil-related items represented 27% of April’s total exports, below the 40% average in 2019. Despite 2021’s rebound in oil prices, lower production remained a challenge since it drove the sector’s export volumes down by -27.2% y/y; however, positive price effects took the overall value of exports up by 108.4% y/y. The value of coal exports also expanded by 7.4% y/y owing to higher prices: production contracted by -3.5% y/y even though the comparison was with the worst month of 2020’s lockdowns. The monthly value of coffee exports increased by a robust 59.96% y/y in April due to both higher prices and greater volumes (up 37.8% y/y).

In May, we expect international trade to have deteriorated owing to the nationwide strike that started on April 28. The coffee industry reported logistical issues amid the road blockades; additionally, some oil fields reduced their production and this is likely to have hit export volumes in the month.

The value of non-traditional exports amounted to USD 1.51 bn in April, an increase of 54.6% y/y compared with a year ago (chart 2, again), but down from March’s USD 1.69 bn, which was the best level since November 2007. Significantly, expanded exports of gold (up 104.8% y/y), manufactured products (up 64.5% y/y), chemical items (a 33.3% y/y rise), and flowers (a gain of 37.3% y/y) drove the overall recovery in non-traditional goods exports.

All in all, April’s exports values again reflected the benefits of higher international commodity prices and better demand for some manufactured products, but supply issues in the traditional export sector provided a weak hand-off to strike-affected May. The extent of further export recovery shall depend on the resolution of the current political situation. Nevertheless, we still see room for additional improvement as the world gets the pandemic under control, solidifies its recovery path, and keeps raising demand for Colombian goods. That said, although exports should keep rising in 2021, imports could see even greater gains as domestic demand expands. As a result, we’ve revised our forecast for the current account balance in 2021 from -3.8% of GDP to -4.0% with a risk that it could be wider, compared with the -3.3% of GDP deficit observed in 2020.

II. April’s lockdowns interrupted the employment recovery in major cities

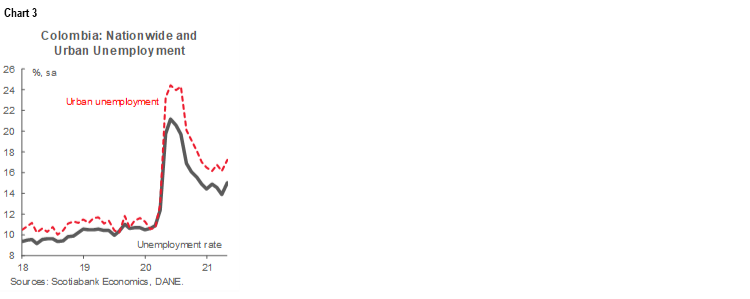

On Monday, May 31, DANE also reported that the April nationwide unemployment rate came in at 15.1%, below April 2020’s 19.8%, but still well above pre-pandemic levels (April 2019 saw 10.3%). At the same time, the urban unemployment rate (i.e., for 13 major cities) was 17.4%, higher than the 16.4% expected by market consensus. Still, it was lower than the 23.5% recorded in March 2020, but higher than April 2019’s pre-pandemic 11.1%. In the seasonally adjusted series, the national unemployment rate deteriorated to 15.0% in April versus 13.9% in March 2021, while the urban unemployment rate increased from 16.1% in March 2021 to 17.2% in April (chart 3).

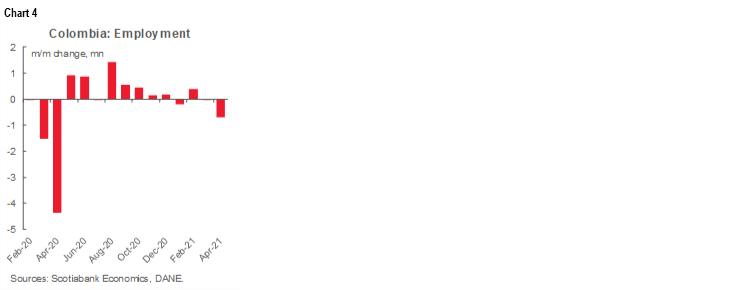

In April, cities on the north coast—including Bogota, Antioquia, and Valle—restricted service-related activities due to the third wave of COVID-19, which heavily impacted labour-market dynamics. In particular, total active jobs fell by -699k, the worst contraction since April 2020 (chart 4), just before the re-opening started. In the same vein, the ranks of the unemployed surged by 211k versus March, which reversed two months of reductions. The number of economically inactive Colombians also increased by 514k in April. The inactive population remains large at 1.5 mn—which implies that only about 66% of people who became inactive due to the pandemic have come back into the labour market.

April’s total active jobs numbers were still down by 1.43 mn positions relative to the pre-pandemic period (April 2019), but compared with April 2020 employment was up by 3.94 mn. Employment reductions remained concentrated in Colombia’s principal cities, which together accounted for 61% of the total contraction in employment compared with the pre-pandemic era.

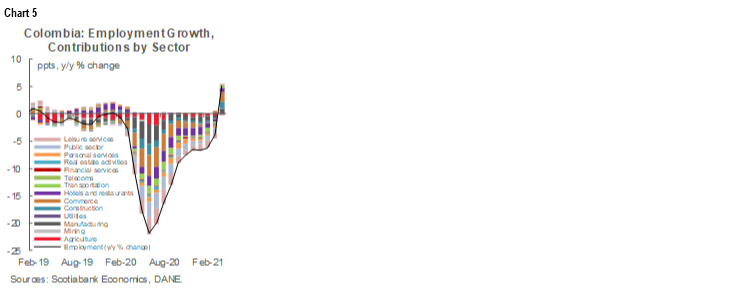

From a sectoral perspective, 80% of employment losses as of April 2021 versus pre-pandemic levels (April 2019) remained concentrated in the manufacturing sector (-519k), leisure (-440k), and the public administration, education, and health sectors (-180k). The 3.94 mn y/y rise in employment in April was mainly driven by commerce (up 859k), construction (up 595k), and manufacturing (up 499k, chart 5). The gap between the female unemployment rate (19.1% versus 23.5% one year ago) and the male rate (12.1% versus 17.3% in April 2020) continued to be a source of concern.

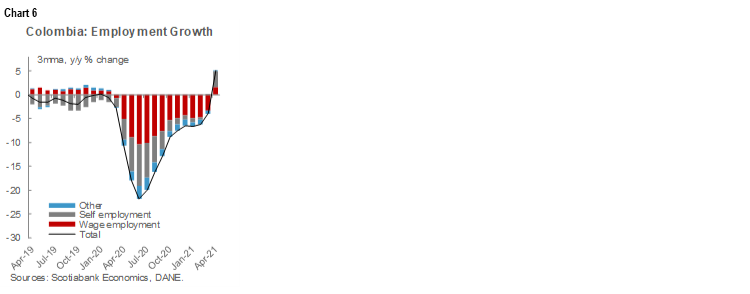

The evolving quality of jobs also remains a worry. Growth in informal jobs continued to lead the overall employment recovery up to April (chart 6). We attribute these dynamics to the relative flexibility of the informal economy. It is worth noting that informal employment increased from a 46.0% share of total jobs in April 2020 to 48.7% in April 2021. The DANE data revealed that the youth unemployment rate stood at 23.1% in April, while 26.6% of the youth population neither studied nor worked—which is a factor in the current round of protests.

Summing up, April labour market data showed a significant impact from the public-health lockdowns implemented during the month, especially in services-related sectors. We expect employment to continue to be impaired in May since the nationwide strike hit a range of economic activities. In Bogota, we could see some green shoots of growth in June: Mayor Claudia López intends to lift major COVID-19-related restrictions during the month. Additionally, other cities could re-open further as the national government works to speed up its vaccination roll-out. At this point, around 6.5% of Colombia’s eligible population has been fully vaccinated.

—Sergio Olarte & Jackeline Piraján

MEXICO: BETTER THAN EXPECTED FISCAL OUTTURN TO APRIL; CREDIT CRUNCH INTENSIFIED

I. Ministry of Finance reported public deficit during January–April

According to reports released on Friday, May 28, by the Finance Ministry, the public balance for the January–April period was a MXN -109.7 bn deficit. Year to date, public revenues rose by 2.4% y/y, but net expenditures were up 4.2% y/y. However, in brighter news, the primary balance came in at a MXN 52.9 bn surplus for the period, well above the MXN -16.4 bn deficit expected in the program.

Dissecting the details:

- Public revenues totaled MXN 2.0 tn (22.6% of GDP), where MXN 271.6 bn came from oil revenues, which rose 54.8% y/y YTD, and MXN 1.7 tn came from non-oil revenues, representing a drop of -3.4% y/y YTD. This compares with a real GDP contraction of -3.6% y/y in Q1-2021, which implies that tax revenues outperformed economic activity. Tax revenues amounted to MXN 1.3 tn YTD (i.e., 14.4% of GDP versus 23.1% in Jan.–Apr. 2020), a drop of -2.8% y/y despite efforts by the government since early-2020 to increase tax collection;

- On the expenditure side, total spending during the first four months of 2021 amounted to MXN 2.1 tn (25.5% of GDP), MXN 28.1 bn below the levels programmed by Congress; and

- April’s “Historic Balance of Public-Sector Borrowing Requirements” (SHRFSP in Spanish), the broad measure of public debt, hit MXN 12.3 tn, equivalent to 51.4% of GDP, down from 52.3% a year ago. Some MXN 7.9 tn represented domestic debt (64.3% of total), and the external component stood at USD 220.3 bn (35.7% of total). Net public-sector debt was MXN 12.3 tn (USD 615.7 bn): net domestic debt amounted to MXN 7.8 tn and net foreign debt rose to USD 224.9 bn.

II. Outstanding credit deteriorated further in April amid weakness in labour market and uncertainty

Bank lending data for April, released by Banxico on Monday, May 31, showed that financing to the private sector continued to contract at a worrying pace. Mexico’s deepening credit crunch reflected both demand- and supply-side factors. On the demand side, weakness in the labour market, soft consumer spending, still-recovering business activity, and a high degree of uncertainty all contributed to sliding demand for loans. On the supply side, tighter standards adopted by banks for new credits likely also helped to drive the decline. At the same time, financing to the federal public sector continued to grow at an unusually fast pace, which could imply some crowding out. In real terms, credit to the private-sector in April 2021 was only about 88% of its pre-pandemic level from March 2020. Similarly, total deposits in April, discounted for inflation, stood at only 96% of their pre-pandemic numbers from March of last year.

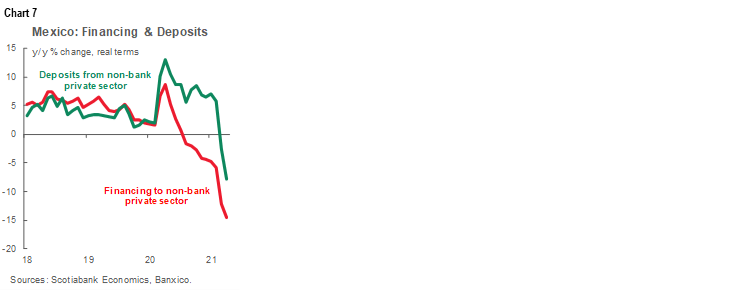

- Total commercial bank financing to the private sector deepened its annual contraction to a new all-time record of -14.4% y/y in real terms in April from -12.2% y/y in March (versus 8.6% y/y growth in April 2020, chart 7). This is the ninth consecutive month in which financing to the private sector contracted in year-on-year terms. Direct financing to businesses also deteriorated further in real annual terms, from -16.1% y/y in March to -19.5% y/y, while consumption financing slightly softened its contraction from -12.9% y/y in March to -12.2% y/y. Growth in mortgage financing moderated from 4.2% y/y in March to 3.0% y/y in April, a significantly slower pace in comparison to April 2020’s 7.8% y/y—despite the attractive levels of interest rates.

- Growth in financing to the federal public sector, almost one third of total new credit, moderated, but still showed solid gains. For April, financing to the federal public sector rose 12.2% y/y in real terms, compared with 20.0% y/y in March and 27.3% y/y a year earlier.

- To sum up, total commercial bank financing to both the private and public sectors registered a record real drop of -7.9% y/y in April compared with -4.5% y/y in March and a gain of 11.1% y/y a year earlier.

Bank deposits have also deteriorated with a record drop of -7.7% y/y in real terms in April, compared with -2.5% y/y in March and a gain of 13.1% y/y in April 2020 (chart 7, again). Base effects likely explained some of the big annual declines in March and April since precautionary savings surged at the onset of the pandemic last year.

—Miguel Saldaña

PERU: APRIL BUSINESS LOAN GROWTH SLOWED; FUJIMORI PLEDGE TO UPHOLD CONSTITUTION

I. Small-business loans led growth with Reactiva resources in April; corporate and consumer loan growth was weak

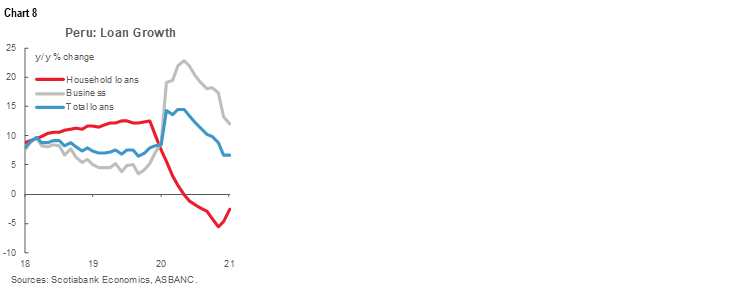

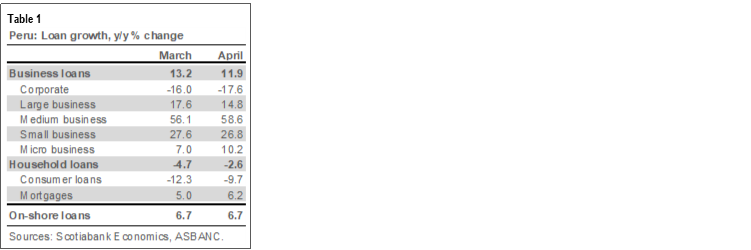

The banking association, ASBANC, released last week information on loan growth in the banking system during April, which we have processed (chart 8 and table 1). Loans in the financial system were up 6.7% y/y in April, the same as in March. Business loans rose by nearly 12% y/y, led by small-business lending that benefited from the Reactiva government-guaranteed loan program. Meanwhile, corporate loans, which are more linked to private investment and which accessed very little of the Reactiva financing, fell by -17.6% y/y. The Reactiva program was launched in April 2020, but most of the funds were distributed beginning in May 2020. As a result, starting in May, a relatively high base for comparison in 2020 is likely to lead to much lower year-on-year growth in business loans. Meanwhile, household loans fell -2.6% y/y in April, led by consumer lending, which was down –9.7% y/y. This reflected at least three factors: the impact of ongoing COVID-19 mobility restrictions on consumption; the reduction in household debt thanks to the additional resources provided by withdrawals from pension funds and worker-compensation funds; and the increasing digitalization of sales. On the other end of the spectrum, mortgage lending rose by 6.2% y/y, in line with the robust real estate sector.

II. Fujimori pledged to uphold democracy and the constitution

Keiko Fujimori made a public oath on Monday, May 31, to uphold Peru’s democracy, strengthen its institutions, defend the constitution, and fight corruption. Fujimori also stated that she was well aware of the doubts that exist surrounding her past and asked for forgiveness for the errors she has committed. The pledge was made with the support of Peru’s Nobel-Prize-winning novelist Mario Vargas Llosa and in the presence of Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo López. The gesture seemed timed for maximum impact before the elections, although it’s hard to say whether voters will be swayed by it.

—Guillermo Arbe

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.