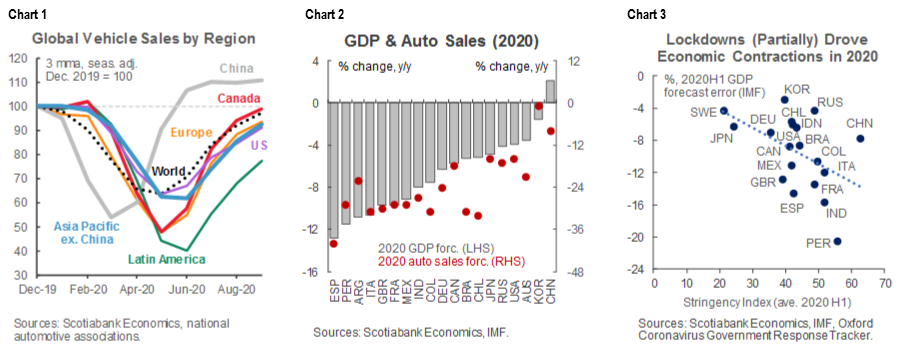

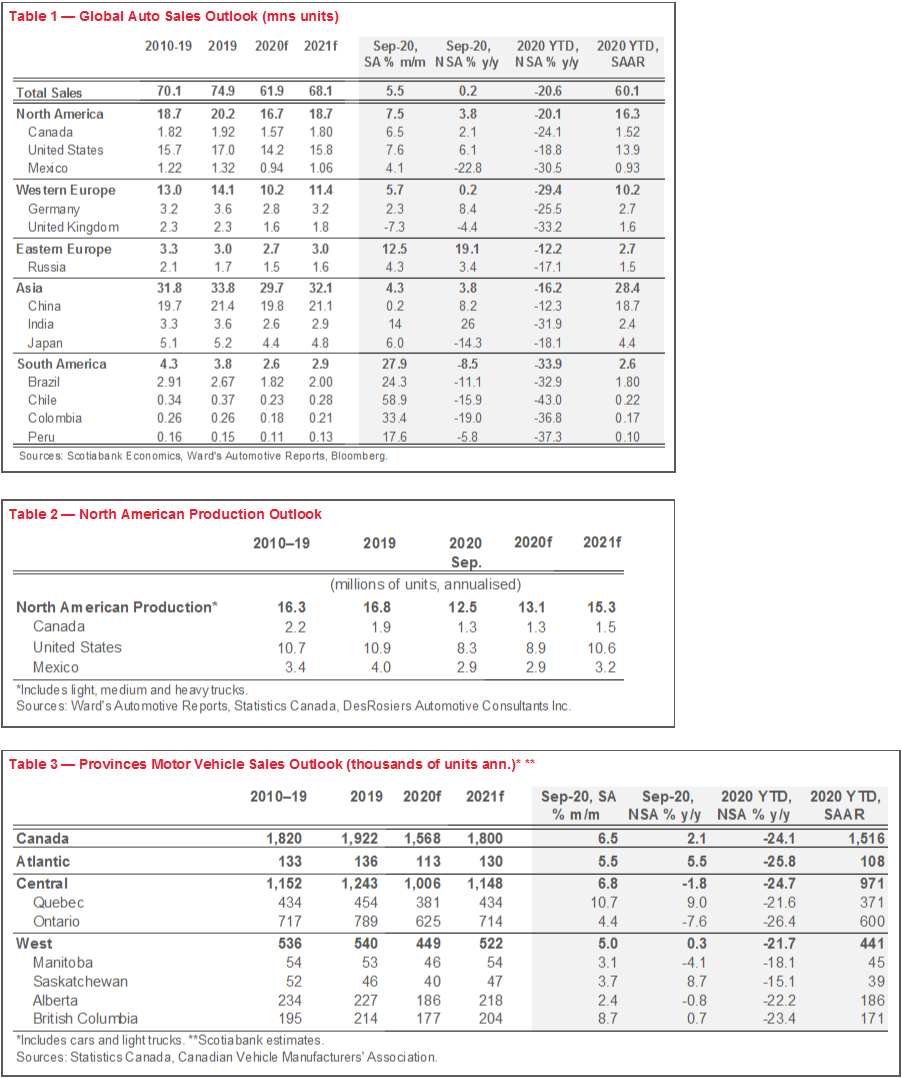

September numbers confirmed an anticipated normalization in global auto sales following robust rebounds in late spring and early summer around the world. Global sales picked up by 5% m/m (sa) in September following a slight deceleration in August.

Chinese auto sales continue to lead the recovery with a healthy 8% y/y increase in sales in September (but flat on a month-over-month basis), while the US and Canada both saw September sales surge into positive territory for the first time on a year-over-year basis (accelerating by around 7% m/m in both markets).

Meanwhile, Western European auto sales are narrowing the gap substantially with steady improvement in sales after more serious retrenchments in the spring (0% y/y, 6% m/m in September), while Latin American auto sales have finally started picking up in September after a challenging summer amidst ongoing COVID-19 outbreaks (-8.5% y/y, 30% m/m).

Global sales sit at -21% year-to-date with final quarter sales expected to face headwinds as COVID-19 second waves surge in many parts of the world.

Sales were already expected to slow heading into the fourth quarter as pent-up demand has largely been exhausted. Persistent supply challenges have also contributed to a more challenging sales environment.

We do not anticipate massive retrenchments in auto sales under second waves as restrictions are expected to be more targeted. However, consumer confidence may modestly dampen sales activity in the near term, possibly pushing out some purchases into the new year.

In this issue, we provide forecasts for global auto sales in 2021. With an expectation that the worst of second waves will be behind us by early next year, we forecast a rebound in the order of 10% next year that would bring sales to within 9% of pre-pandemic levels.

BUSINESS AS (UN)USUAL

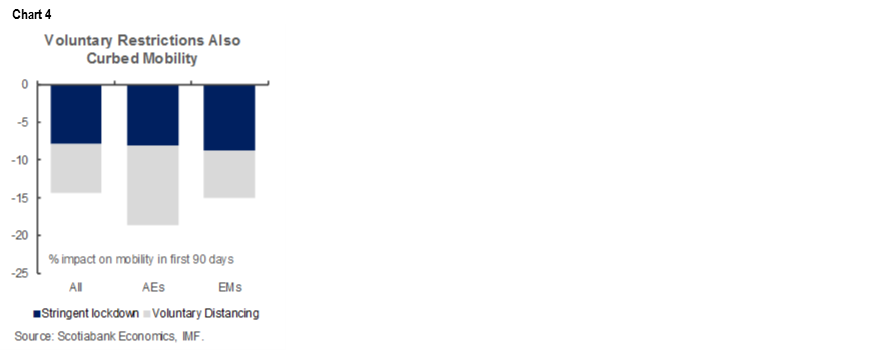

Global auto sales so far this year have challenged traditional forecasting capacities with exceptionally strong rebounds (chart 1). On the one hand, GDP performance has been a good (but lagging) indicator of the general depth and direction of auto sales (chart 2). But GDP in turn has been heavily influenced by the stringency and duration of government-imposed lockdowns as opposed to pure economic fundamentals (chart 3). Furthermore, severe shutdowns were often coupled with substantial government transfers that otherwise offset the contractionary impacts of traditional indicators such as unemployment that would normally curb purchases such as automobiles. Supportive financial conditions and loan and tax deferrals also played a role in this regard.

Auto sales are typically discretionary purchases that can be timed to economic circumstances and confidence levels. Following the Global Financial Crisis, the auto sales recovery was multi-year in most advanced economies. Canada returned to pre-crisis sales levels only 5 years later and 7 years in the US. Monthly sales activity only turned modestly positive on a year-over-year basis after the first anniversary of the crisis when base effects came into play. Today, auto sales in both of these markets turned positive on a year-over-year basis in September only five short months after the peak of shutdowns. This speaks to both the non-economic nature of the downturn and the fact that governments have taken the brunt of the impacts so far on their own balance sheets.

As markets grapple with second waves, experience from the spring can inform activity over the next few months. Notably, sales will likely face headwinds as confidence wanes in light of rising health risks even if governments do not mandate shutdowns. In a cross-country analysis, the IMF recently concluded that almost half of reduced mobility trends stemmed from voluntary behaviours as opposed to imposed constraints, and this effect was even more pronounced in countries where there was a higher virus prevalence (chart 4). This is consistent with auto sales performance in countries such as Sweden where sales are down -21% year-to-date even though dealerships were never closed.

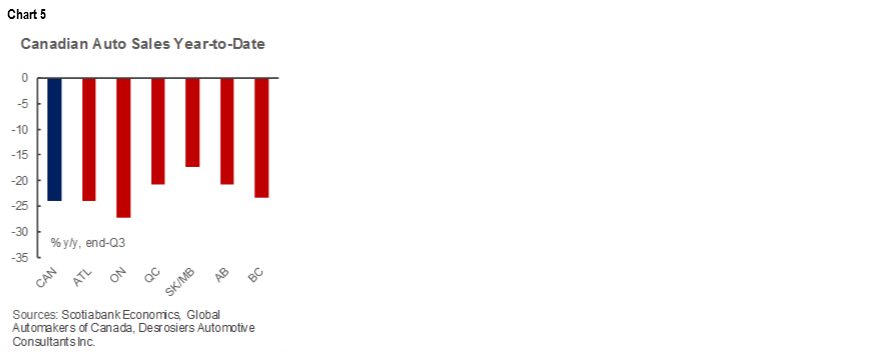

Within Canada, preliminary September sales data suggests auto sales dipped in Ontario despite a positive national print in auto sales as COVID-19 cases had started to pick up in that province. Otherwise, Ontario posted a healthy uptick in jobs that month. Clearly, one data point does not establish a trend but it signals something to watch. Overall, across provinces, Ontario auto sales are posting the sharpest declines at the end of the third quarter (chart 5) that are more a reflection of the more stringent and longer lockdowns, particularly for its largest cities, whereas declines in oil-producing provinces have been more muted so far despite a more serious economic impact from oil shocks. Stalled immigration inflows may also be weighing on Ontario sales—as by far the largest recipient of new Canadians.

On the positive, consumer concerns emanating from health risks versus economic uncertainty are more likely to shift out demand as opposed to destroying it. The continuation of fiscal supports may play an important role in ensuring that the former holds under second waves. This will also likely be a differentiating factor in sales across countries as some have exhausted fiscal space or have reached political impasses to providing additional supports. As discussed in last month’s issue, the pandemic may have also created new demand out of fears related to public transit and ride-sharing which could still linger at least through the early part of 2021.

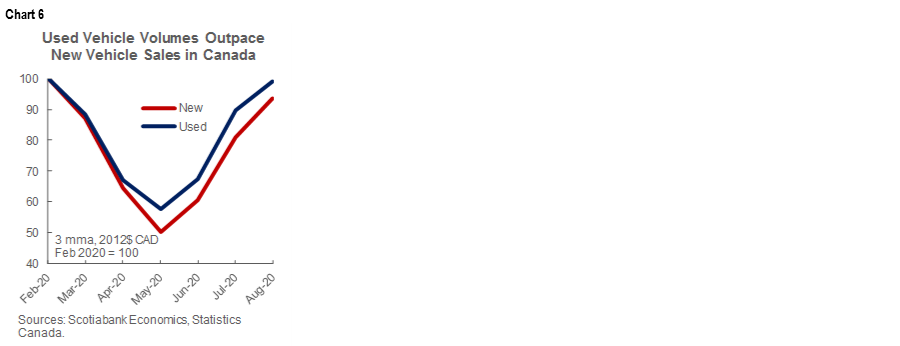

There could also be more upside next year from used auto sales which tend to operate counter-cyclically. In addition to affordability concerns in a downturn, price drops typically fuel this pattern. Exceptionally in this downturn, used vehicle prices in Canada (and other markets) have rebounded substantially after an initial drop in the spring, likely owing to supply constraints given lease extensions and loan deferrals, as well as a weak Canadian dollar that has diverted limited supply to the US. Government policy supports have also likely underpinned strong demand for both new and used vehicles, which has supported stronger prices. Consequently, retail sales volumes (in dollar terms) of used vehicle sales modestly outpaced those for new vehicle sales through August (chart 6). With used vehicle prices anticipated to soften over the next few quarters as supply increases, unit sales of used vehicles should accelerate at a faster pace through the recovery.

Broadly speaking, the global policy environment is expected to be highly supportive over the next couple of years. While 2021 should herald solid economic rebounds for most markets, spare capacity will likely still persist in all major economies through 2021 and into 2022—including elevated unemployment—that would warrant continued accommodation through monetary and fiscal policy. Auto sales should continue to strengthen as economies advance through this recovery, benefiting from low financing costs and an improving employment outlook. As travel slowly resumes in the latter part of 2021, a pick-up in fleet demand should also underpin a stronger auto sales environment. A more balanced supply environment should also alleviate some sales constraints.

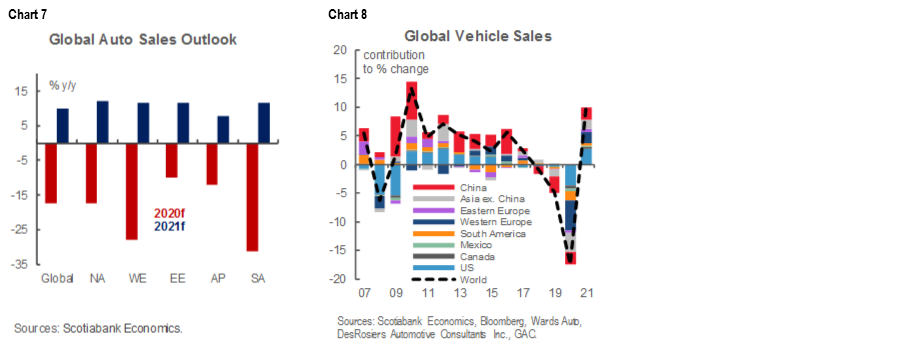

We expect global auto sales could rebound by around 10% in 2021 though sales would still sit 9% below 2019 pre-pandemic levels (charts 7 & 8). Differentiators across countries and regions include the depth of the sales decline in 2020, as well as the expected path of economic recovery in 2021. For example, we anticipate a rebound in Chinese auto sales of about 7% in 2021 in light of a shallower retrenchment in 2020 (currently estimated at -8% y/y). This will bring sales just 2% shy of pre-pandemic levels. Japan is similarly expected to post a relatively smaller sales decline in 2020 (-15%), with an anticipated rebound of about 9% in 2021, but would leave sales still down by 8% relative to 2019 given its more mature market and fewer targeted supports for auto purchases.

Western European countries are expected to suffer far worse declines in 2020 (-28% y/y). This should support a mathematically stronger rebound in 2021 in the order of 12%, however, given a slower economic recovery path (as well as regulatory headwinds), auto sales will still likely be about 20% below 2019 levels. Differences are expected within the region; for example, Germany’s auto sales recovery in 2021 should bring it to about 88% of pre-pandemic levels, whereas UK sales are expected to recover to only about 78% as a weaker economic outlook is expected to dampen its auto sales rebound.

South America broadly faces dynamics similar to those in Europe, namely, steep declines in 2020 auto sales (-31%) that should support technical rebounds in 2021 (12%). However, Brazil as the largest auto market dominates these headline numbers. Its more mature market and protracted recovery suggests a slower auto sales rebound in 2021 (9%) to about 75% of pre-pandemic levels, where smaller markets including Chile, Colombia, and Peru could see rebounds in the range of 15–20% in 2021 after facing declines well-above 30% in 2020 for the most part.

North American headline forecasts mask differences within the region. Canada faces a potentially stronger auto sales rebound in 2021 (15%) versus the US rebound forecast (12%) owing to steeper declines in 2020. Relatively similar economic recovery paths would bring auto sales to within 7% of pre-pandemic levels in 2021 in both countries. Mexican auto sales, on the other hand, expect to see far steeper declines in 2020 (-29%), but a longer recovery in auto sales mirroring its economic recovery. A forecasted 13% rebound in 2021 auto sales would only bring sales to within 80% of pre-pandemic purchases.

Needless to say, the confidence levels around these forecasts are unusually wide given the unprecedented nature of the crisis, the uncertainty around the course of the virus, and importantly, the policy responses and consumer behaviours. Stronger policy supports—for example, substantial new stimulus spending in the US or targeted tax breaks for auto purchases in China—could drive stronger recoveries. On the other hand, persistent pandemic effects that linger beyond early-year could erode sales activity if governments are unable to bridge broad-based and prolonged slowdowns.

Details on forecasts for 2020 and 2021 are included in Table 1 (back).

*All numbers reported are not seasonally adjusted (nsa), unless otherwise indicated (sa).

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including, Scotiabanc Inc.; Citadel Hill Advisors L.L.C.; The Bank of Nova Scotia Trust Company of New York; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Limited; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa S.A. de C.V., Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., and Scotia Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.