- Headline job growth missed expectations…

- ...as education sector jobs fell

- There was job destruction excluding call backs of furloughed workers

- The number of permanently laid off continues to rise

US nonfarm payrolls m/m change 000s / UR (%) / wage growth y/y (%), SA, September:

Actual: 661 / 7.9 / 4.7

Scotia: 1000 / 8.0 / 4.8

Consensus: 859 / 8.2 / 4.8

Prior: 1489 / 8.4 / 4.6 (revised from 1371 / 8.4 / 4.7)

A gain of 661,000 jobs is nothing to shake a stick at, but there are two reasons why it’s generally disappointing. Market participants should be increasing the odds of resuming very weak or negative payroll numbers. This is not a certainty but it would require a rapid change in favour of organic job growth. The initial market reaction was muted as more of the focus remains on Trump’s diagnosis, US stimulus talks and Brexit headlines.

First, take callback effects out of the picture and there was net job destruction. As chart 1 demonstrates, the number of unemployed folks on temporary lay off and brought back on payroll fell by 1.52 million to 4.64 million. In one sense this is welcome because it takes the number of furloughed workers down from a peak of 18.1 million to 4.2 million which is encouraging. This figure could continue to decline to the pre-covid level of about 750k but the issue is whether they all get called back or just get converted to permanent layoffs and whether they give up searching for work.

In another sense, however, excluding this effect from the headline means jobs excluding call backs fell by 859k. That indicates net job destruction, or the inability of the US economy to generate organic job growth. This will become a more important factor going forward as the number of furloughed workers continues to decline if organic job growth does not pick up. It amplifies the risk of renewed net job losses.

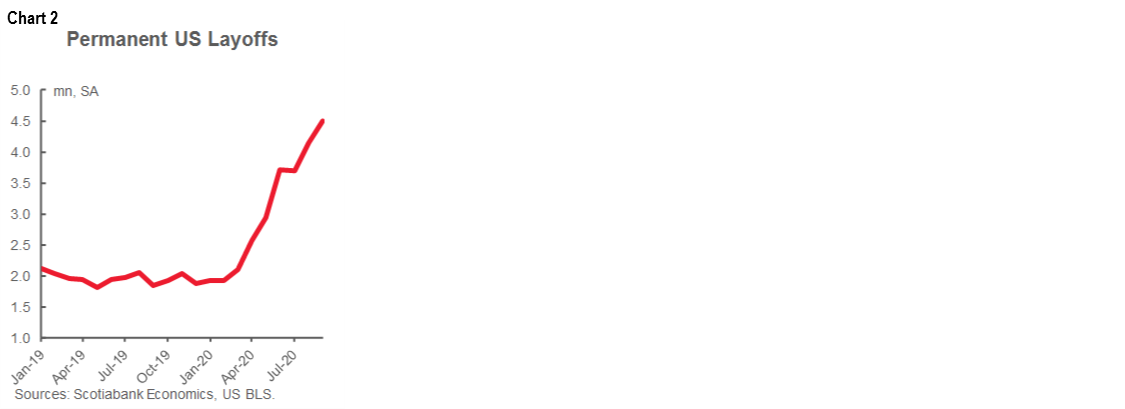

You can see this in terms of the rising number of outright job losses in the US. Permanently laid off workers not expected to be called back continues to rise (chart 2). That figure is now at its highest since November 2013. It’s not done climbing yet but remains well shy of the GFC peak of 8.3 million. As another indication of the issue at hand, note the growing wedge in chart 1 between what is happening to aggregate payrolls versus the temporarily laid off which confirms that ex-callback jobs are being lost.

The average duration of unemployment is climbing and is at 20.7 weeks now, but that restores it to where it was pre-covid. This is a distortion as people left the workforce initially. Now that this has stabilized, the real test begins in terms of duration of unemployment.

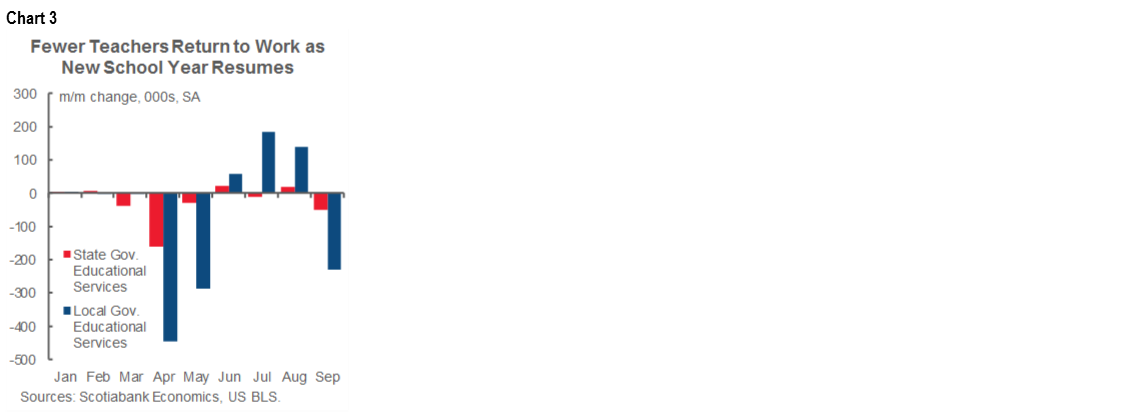

The second reason why the report is disappointing is that the main reason why the 661k figure fell shy of expectations had to do with job destruction in the education sector (chart 3). Education sector jobs at local governments fell by 231k while they fell by 49k at state governments for a combined hit of 280k. The case for removing this effect from the headline miss is that it is a narrow distortion that masks what is going on in the underlying private sector. The case for not removing this hit is that a job is a job and these are generally good jobs we’re talking about. I lean toward the latter interpretation in terms of not fading the headline miss as the lingering impact of covid-19 continues.

Why did this education sector hit occur? One possible argument is the hit to state and local government finances in the absence of further stimulus from Washington. Another possible reason is that teachers and other education sector workers were reticent to return to work in the midst of the pandemic. A third reason is that fewer of them were needed as schools shifted toward more on-line content.

The Federal government also shed 34k workers. Overall, the public sector dropped 216,000 jobs with the only offsetting bright spot being that local governments added 96k jobs outside of education. This, in turn, might suggest that the issue is less about local government finances than it is about the other factors influencing education sector jobs.

There was otherwise decent breadth across the sectors as shown in chart 4. Goods sector employment was up by 93k with services up 784k. Within goods, there was a 66k rise in manufacturing employment and a 26k rise in construction jobs. Within services, leisure/hospitality was up 318k, retail was up 142k, and other trade/transport up 95k.

Hours worked came in strong at 1.1% m/m on the callback effect.

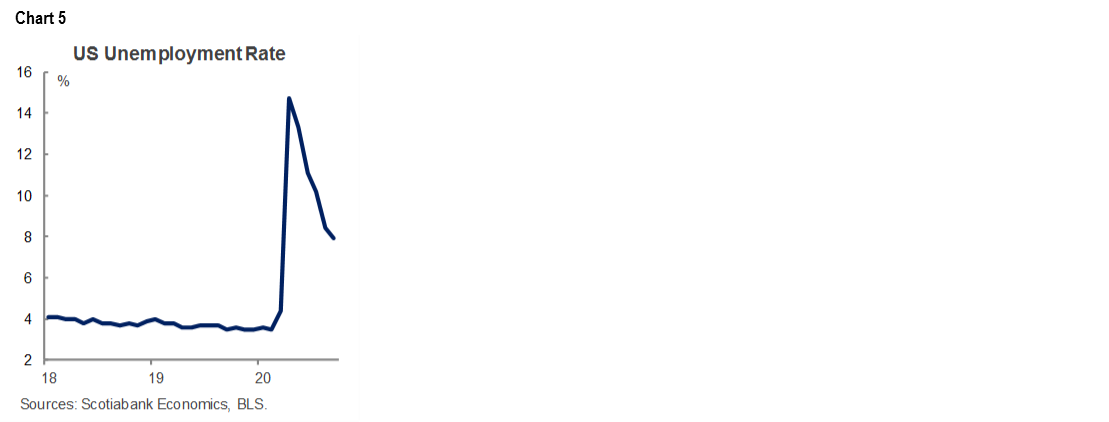

The unemployment rate declined to 7.9% from 8.4% mainly because people left the workforce (chart 5). It is derived from the companion household survey which showed job growth at 275k but a 695k shrinkage in the size of the labour force. The participation rate fell three tenths to 61.4%.

Wage growth was in line with expectations at 0.1% m/m and 4.7% y/y (chart 6). It remains high because of the ongoing pandemic distortion that resulted in a disproportionate hit to the jobs of lower than average wage workers. Thus, 5% wage growth is not to be treated as a good sign.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including, Scotiabanc Inc.; Citadel Hill Advisors L.L.C.; The Bank of Nova Scotia Trust Company of New York; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Limited; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa S.A. de C.V., Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., and Scotia Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.