- BoC hiked 50bps as expected…

- ...and sure sounded like it’s on a predetermined path toward much higher rates

- An upward revision to the neutral policy rate implies a greater need to tighten

- Quantitative tightening is here…

- ...as the BoC will cease buying in both the secondary and primary markets…

- ...but it should also consider outright asset sales

- BoC fears unmoored inflation expectations

- BoC stands by the existing rate corridor…

- ...and sounds as uncertain as the Fed toward optimal settlement balances

- A more circumspect central bank in 2021 could have avoided such a hasty retreat

The Bank of Canada largely met our long-held expectations for policy moves and the broad tone of its forecasts. Markets mostly shook it off which probably pleases the central bank. CAD appreciated, but that was more USD-driven against a variety of crosses including the euro. Two-year and five-year GoC bond yields were minimally affected and are underperforming bigger declines in the US. There are nevertheless important nuances to the overall suite of communications that could affect market interpretations.

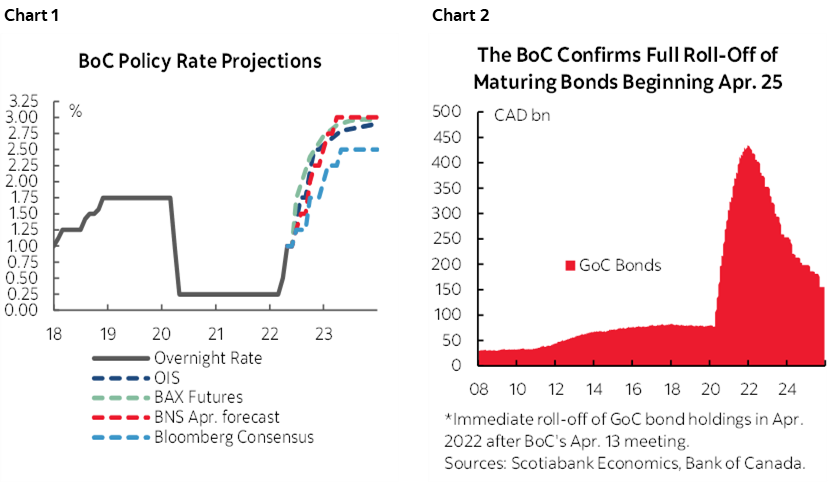

Please see the original communications in the statement (here), Governor Macklem’s opening press conference remarks (here) plus the market notice (here). Also see charts 1 and 2 that show our projections for the policy rate compared to consensus and markets along with our projection for the BoC’s holdings of Government of Canada bonds.

Here is what they did combined with my views throughout.

POLICY RATE HIKED 50BPS

The overnight lending rate was increased by 50bps to 1%. That matched broad expectations among economists and traders. Scotiabank Economics was a first mover in formulating such expectations before the BoC’s speech on March 25th that dropped “forcefully” on markets. Lending rates linked to the overnight rate like Prime will be going up by an identical amount. Because the five-year Government of Canada bond yield has mostly priced the expected future rate path in the move from about a ¾% yield until last September to 2½% now, there may only be modest further impact upon best-offer five-year mortgage rates.

FORWARD RATE GUIDANCE—SORT OF, MAYBE, KINDA PRE-SET

The BoC does not formally sketch out a path for policy rates like some other central banks (e.g. the RBNZ) and instead uses verbiage and forecasts to more generally guide its intentions. I found that the indirect forward rate guidance that was offered today was somewhat at odds with itself and confusing to market participants which may explain part of why markets did not really know what to do with it by way of incremental information.

On the proverbial one hand, the statement itself continued to sound conditional:

"The timing and pace of further increases in the policy rate will be guided by the Bank’s ongoing assessment of the economy and its commitment to achieving the 2% inflation target."

And so did the references to how policy is not on a pre-determined path. So far, this all sounds very conditional upon the further evolution of data and particularly as it translates into tracking inflation and inflation risk.

Yet Macklem dropped a bomb in the press conference that indicated policy may very well be on a pre-set path. He did so by saying three things.

- First was that a 50bps hike today reflected a need to normalize monetary policy relatively quickly. That doesn’t sound very conditional and does sound like policy is on at least somewhat of a pre-set path.

- Second is guidance offered by Macklem in the press conference that the BoC will get up to neutral before they face uncertainty over whether to then pause or perhaps go higher than the neutral policy rate. In other words, a pause isn’t likely to be forthcoming until they achieve a neutral policy rate.

- Third is that Macklem repeated guidance that the central bank will act “forcefully if needed” which as we saw with today’s decision is code language for moving in greater than 25bps increments.

What does this mean in terms of pace by individual meeting? The BoC is saying well, policy is not on a pre-set path except that it is but it won’t be if something skids in the ditch and so we’ve decided to cover ourselves by confusing everyone. Huh?! If Q2 really does look like it's accelerating over a much better Q1 than they had thought and coming inflation reports including next week's continue to rise, then it may be that getting to neutral quickly before pausing means they could well hike 50bps at a time in each of June, July and September. That would land you in the middle of the 2–3% neutral rate range inside of six months before a pause. It may prove to be more extended than that, but the point is to leave the door open to a series of larger than normal hikes. Like opening a bag of potato chips, one goes for the biggest ones first and then leaves the busted bits for later.

NEUTRAL RATE REVISED HIGHER—IMPLIES GREATER NEED FOR POLICY TIGHTENING

So what is ‘neutral’? By definition, the nominal neutral rate is the estimate of the policy rate that should exist when the economy is in a full state of equilibrium with balanced supply and demand conditions and inflation on the 2% target.

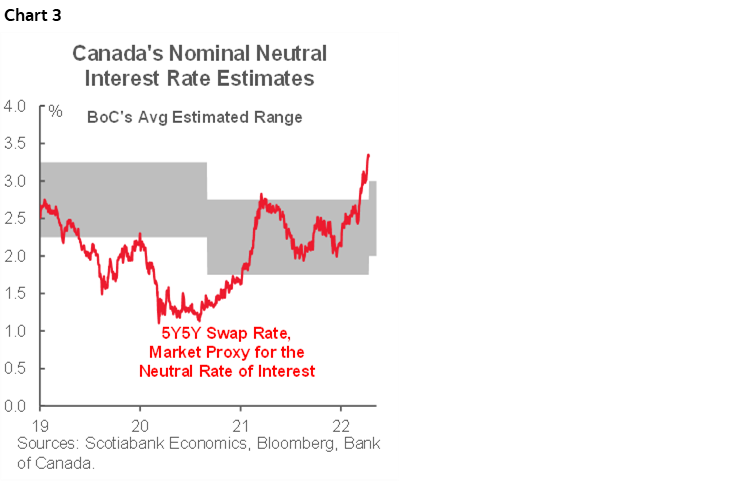

In practice, nobody really knows what this number is, but the BoC raised its estimate of this magic bullet number by 25bps to 2–3% from 1.75–2.75% which is where they had lowered it back in October 2020 and through last April’s update. Basically, the BoC is saying that the pandemic-driven reason for lowering the neutral rate range has expired and they’ve now reverted to the prior estimated range.

The rationale that was offered for adjusting the neutral rate range higher to 2–3% is basically that they revised their US neutral rate range higher as an input and it now matches the FOMC’s 2.5% midpoint of a range. Right, so one country’s made-up estimate justifies the other country’s made-up estimate! That seems a tad arbitrary to me. Other drivers of changing the neutral policy rate estimate are mixed. Labour force growth is not scarred to the degree once thought by the BoC as the job market has more than fully recovered in aggregate and Canada has raised immigration targets which could imply reason to raise neutral rate ranges, yet productivity growth is downright awful and falling outright during the pandemic which it that lasts would merit a lowered neutral rate range.

Still, if the BoC thinks the neutral nominal policy rate is now a bit higher, then that implies that it thinks present policy is more stimulative than it had previously judged. That’s because of the greater distance to a now higher estimated neutral policy rate. In turn, that slightly intensifies the pressure to tighten even more excessively stimulative monetary policy than the BoC had previously thought itself to have delivered.

Also note that a market proxy for the neutral policy rate is higher than the BoC’s revised range (chart 3). Then again, everyone from economists to the central bank and traders are guessing at the neutral rate.

QUANTITATIVE TIGHTENING—AND NO BUYING IN THE PRIMARY MARKET

As expected, the BoC will stop buying any Government of Canada bonds effective on April 25th with the final operation on April 21st in the 10-year sector. That means two things. For one, the BoC had been buying at an approximate gross pace of $4–5B/mth in order to roughly keep the net portfolio of bonds roughly constant over time as lumpy maturities countered such buying with maturing bonds falling off the balance sheet. That will stop on the 25th. Then on May 1st the BoC’s C$12.6 billion holding of a GoC bond will mature and drop off the balance sheet without replacement.

In addition, the BoC will no longer buy in either the secondary or primary market at auction. That’s a new twist as explained in the market notice (here). That’s material because as recently as the March 3rd speech, Governor Macklem had said “We’ll consider whether for technical reasons we’ll still have primary purchases but there will be no secondary market purchases.” Macklem did not offer any explanation for the decision which would seem to be a rather glaring oversight.

Macklem also said “We don't see the need to actively sell bonds.” The BoC is therefore fully relying upon no buying in the primary and secondary markets coupled with the maturity profile of its holdings to shrink its Government of Canada bond portfolio going forward.

Chart 2 again shows the pace at which this is likely to occur and how it will remain big and gloated for quite a while at levels well above the pre-pandemic starting point. In my view, the fact that markets shook off the primary market rejection with no material effect on yields and term premia indicates further support for my view that they should shrink the balance sheet more aggressively. They have a window in which to do that with very limited effect on Canadian rates relative to the influences of the Fed’s actions going forward and should exploit it. At a minimum, the BoC should emulate the RBNZ’s managed sale approach if not announce a more deliberate plan.

The BoC did not venture to guess at the rate equivalence to shrinking its balance sheet. That’s probably because of some combination of not having been asked and not really knowing. My view remains that there is little if any equivalence. BoC research has tended to estimate the announcement effect of the Government of Canada bond buying program to have been a paltry -10bps and the flow effect at individual operations to be “modest” and transitory such that it disappears within about four trading days on average. Chart 4 shows that there was no readily apparent impact of withdrawing the BoC’s purchase program between October 2020 and October 2021 while the Fed kept buying by the truckload. I think the Fed’s QT plans matter, but the incremental effect of the BoC’s QT plans over and above the imported effects of the Fed’s actions and other drivers has been de minimis. The fact that markets shook off the news that the BoC wouldn’t buy in the primary market adds to this argument about minimal rate equivalence.

FORECASTS—STRONGER GROWTH AND INFLATION

On inflation, they pushed out guidance to hitting the 2% target into 2024 as expected. They now say that "CPI inflation is now expected to average almost 6% in the first half of 2022 and remain well above the control range throughout this year. It is then expected to ease to about 2½% in the second half of 2023 and return to the 2% target in 2024." Chart 5 shows their updated forecasts and how they have evolved to today’s mea culpa. The BoC is forecasting currently official CPI inflation figures but bear in mind inflation will be ratcheted materially higher hopefully soon when StatCan adds used vehicles to the CPI basket.

The cautions about inflation expectations also met expectations: “There is an increasing risk that expectations of elevated inflation could become entrenched." I think they already have. This is on the back of movements in market break-evens and the BoC’s surveys that increasingly show consumers and businesses do not believe in the BoC’s 2% target.

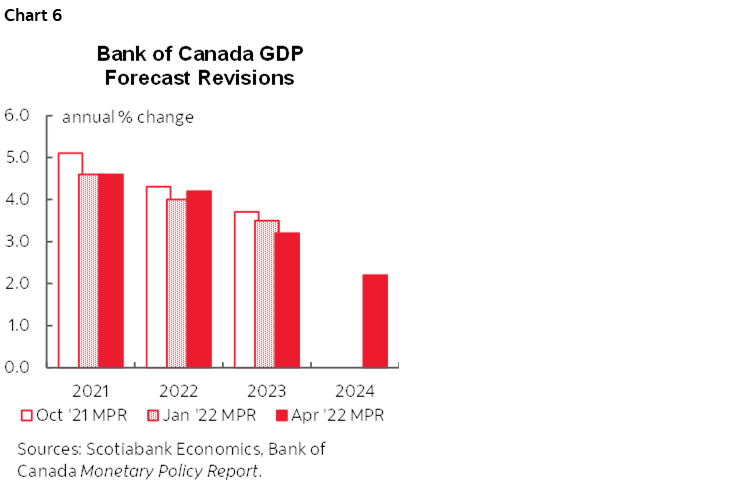

On growth, the BoC flagged stronger than expected Q1 growth and said growth "is likely to pick up in the second quarter" so they are adding to the Q1 momentum. They are a bit higher than us on growth in Canada at 4 ¼% this year and 3 ¼% next year (we have 4.2% and 3.0% respectively). See chart 6.

The BoC also played with potential GDP growth estimates. They now think that potential GDP growth excluding temporary factors will be 1.7% this year (from 1.3% previously) and 2% next year (unchanged) and followed by 2.3% (from 2.2%) in 2024. Slightly higher potential GDP growth this year when weighed against strong growth in actual GDP means that the economy would not be moving into as material excess aggregate demand than had they left the potential GDP estimate of the economy’s noninflationary speed limit unchanged. Frankly I wish they’d quit fiddling with decimal points on numbers that are so highly uncertain.

In any event, the implication is that the economy has pushed into greater excess demand to this point than the BoC had anticipated and will continue pushing into excess demand conditions going forward. The debate over what’s driving inflation is long behind us. A combination of supply-side factors and net excess aggregate demand is driving inflation while markets, businesses and consumers are not fussing over what’s causing it while they extrapolate such expectations. The result is that the BoC is on the defence in terms of convincing everyone it is serious enough about its inflation target.

MAINTAINING THE RATE FLOOR SYSTEM, UNCERTAIN TOWARD SETTLEMENT BALANCES

The same market notice that outlined the QT plans also referenced how the BoC would maintain the current rate corridor. Instead of reverting back to the pre-pandemic system that set the deposit rate a quarter-point below the overnight lending rate, the BoC will continue to maintain a rate corridor system that sets the overnight deposit facility rate equal to the overnight rate target. It guided that this system will remain in place “even after quantitative tightening has run its course and the balance sheet has diminished in size to the point where the Bank needs to start acquiring assets again for normal balance sheet management purposes.”

The BoC remains uncertain toward the longer-run level of settlement balances but guides that “it is far lower than the current level” which should shock no one. It said it will determine this level based on a range of monetary market indicators as well as external input. This is somewhat akin to the challenge facing the Fed that does not know when QT will end and what the level of optimal reserves is within the US system. Both central banks will likely find out these thresholds once they’ve hit them!

FEDERAL BUDGET IMPACT MUTED

Macklem was asked if the Federal Budget prompted any additional tightening and replied that the new measures in the budget are about $30B over the next five years which is a positive impulse but “would not materially affect our projections.” He’s probably right in that sense, but there are at least two cautions here. I believe the cumulative effects of heavy government spending throughout the pandemic that has not been reduced is supporting elevated inflation. I also think that going forward there are likely to be additional spending increases by the left wing Liberal-NDP pact as major goals like pharmacare are waiting in the wings and probably for delivery closer to a future election.

I would have liked to hear Macklem broach the topic of real policy rates. Even by the end of 2023 they are just getting toward a real policy rate of around zero given his 2–3% neutral rate guidance objective and their 2.4% y/y inflation forecast for the end of 2024. We will still have extreme monetary stimulus in real terms throughout then which I still think a lot of folks don't get.

CONCLUSION: A SLOW FOOTED BOC HAS RAISED ECONOMIC ANXIETY

Overall, we’re now getting more expedited withdrawal of excessive monetary policy stimulus because I think the BoC waited far too long to pivot on inflation. It’s a ruse to hide behind the Ukraine war as new information to merit a policy pivot. The BoC spent almost all of 2021 until December thoroughly dismissing any talk of longer-lived inflation. I had been warning of inflation risk since late 2020 only to hear the BoC routinely slap that down. Rubbish. Had it been more humble, circumspect and hence open to two tailed arguments rather than so wedded to its view that inflation would fade very quickly and was distorted and narrowly based, then they could have begun tightening earlier and even earlier than had they not blown off a market gift in January. Instead, Canadians are paying the price with runaway inflation and in terms of the economic anxiety caused by the need to tighten more rapidly and perhaps to a greater cumulative peak than would have otherwise been the case. Recognizing that emergency conditions had passed much earlier could have meant a more gradual adjustment to borrowing costs and less uncertainty over the impact of a series of aggressive moves on the broader economy. Not all central banks were as guilty of this; the RBNZ, for instance, was considerably ahead of the BoC in its shift to a tightening stance. By contrast, both fiscal and monetary policy circles in Canada maintained excessively stimulative conditions for far too long and the two main instruments of public policy will be at loggerheads going forward.

Please see the accompanying statement comparison.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.