- Another solid job gain was recorded…

- ...and looked mostly decent under the hood

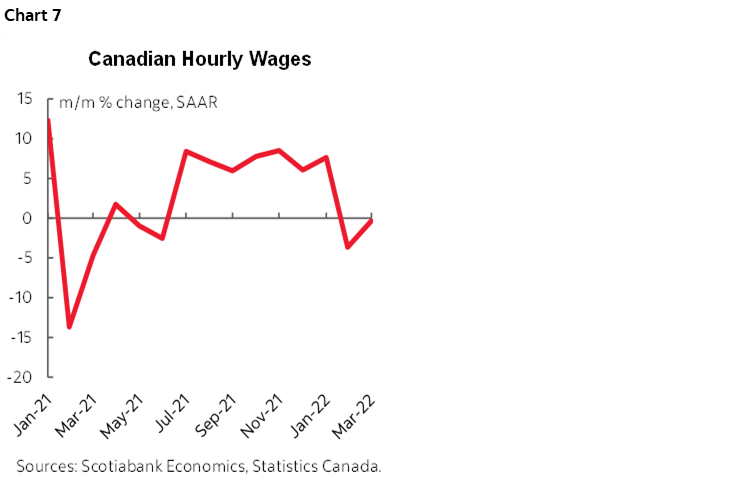

- Wage growth stumbled again

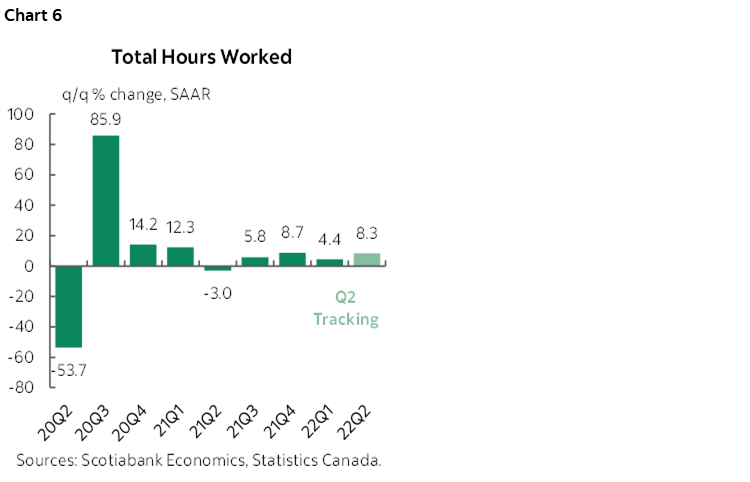

- Soaring hours worked point to a strong 2022H1 economy…

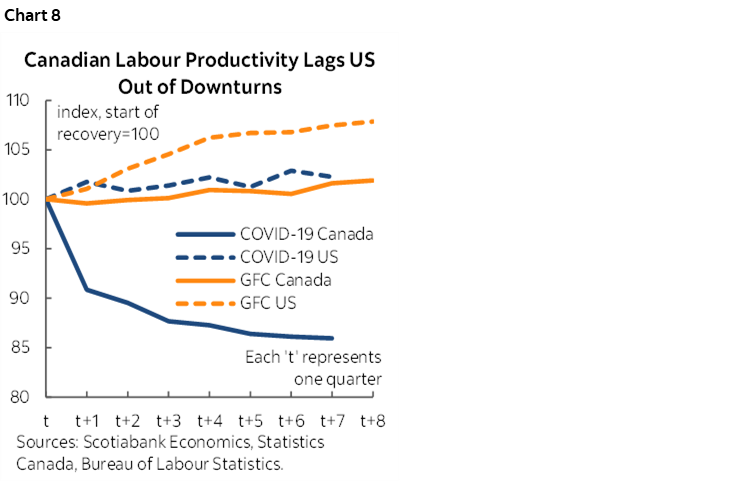

- ...but productivity is worsening….

- ...and that’s not good for living standards, the economy and future fiscal balances

- The BoC will stay on track with a bigger hike and ending reinvestment next week

CDN jobs / UR, m/m 000s // %, SA, March:

Actual: 72.5 / 5.3

Scotia: 125 / 5.2

Consensus: 79.9 / 5.4

Prior: 336.6 / 5.5

Canada posted another healthy job gain as the economy at least temporarily distanced itself from omicron into the March reference week. Highlights are shown in chart 1. CAD and Canada yields were little affected by the release.

The broad details were generally constructive as noted below. Flies in the ointment include another month of weak wages, worsening labour productivity and the forward-looking question mark over resilience in the face of the country’s sixth wave of COVID-19 cases. The pairing of the first two observations together is inflationary on net as the labour market is getting tighter and tighter.

On balance that means that the overall report is unlikely to sway the Bank of Canada’s decisions next Wednesday as it stays on track toward what we expect to be a half percentage point hike in the overnight rate and full quantitative tightening via 100% roll-off limits.

A VERY TIGHT LABOUR MARKET

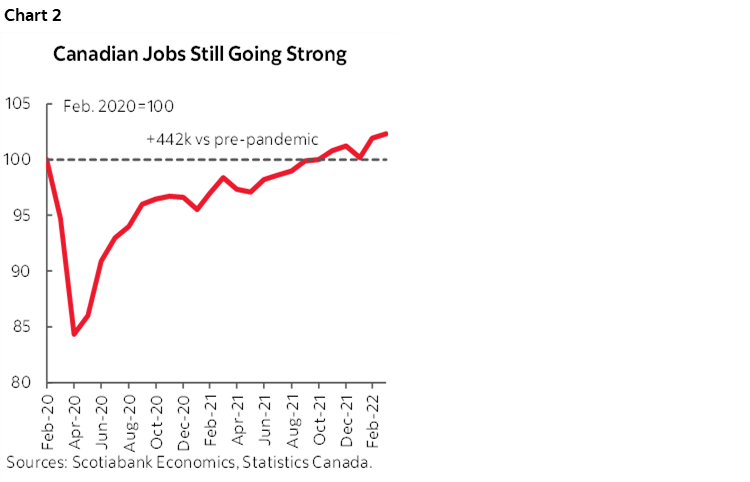

Canada is now 209k above pre-omicron employment levels back at the end of December. Canadian employment is now 442k higher than pre-pandemic levels (chart 2) while the US household and nonfarm measures are still net down by a fair margin. The US has had some retirements whereas evidence of such is lacking in Canada, but I still think that Canada's labour market is materially tighter than the US. That has come at the expense of relative productivity growth which means higher inflation risk all else equal north of the border than south.

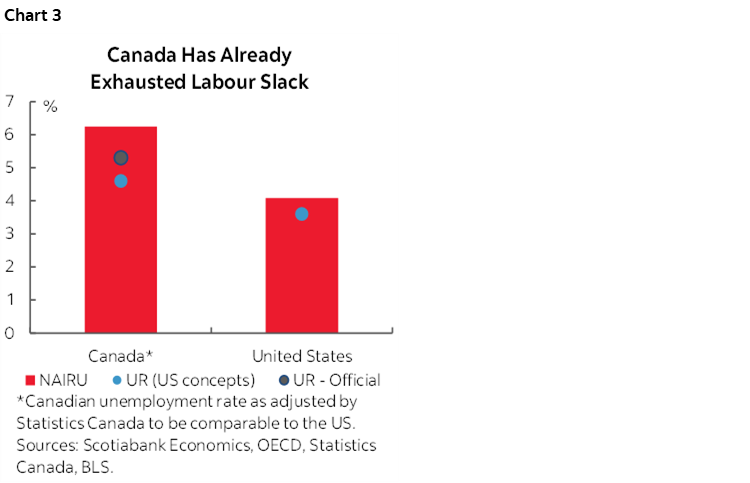

How is Canada’s job market tighter? For starters, if Canada measured the UR like the US does then its 4.6% adjusted rate is only 1.0 ppt above the US at 3.6%. Canada uses a more liberal and relaxed definition of what constitutes searching for work and for some reason starts counting folks at 15 versus 16 years of age, among other methodological differences.

Further, Canada's R8 all-in measure of underemployment that includes discouraged workers, folks working part-time who'd prefer full-time etc sits at 8.3% versus the US U6 measure at 6.9%. This measure, however, is not adjusted for methodological differences. StatCan only does that for the traditional URs.

But unemployment rates only capture part of the slack argument. They have to be expressed relative to highly uncertain estimates of how low they can go before wage pressures are ignited. Each country has different trip points. So where does Canada stand in terms of labour slack? If the unemployment rate measured similarly to the US is only slightly higher, but most estimates of Canada's NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) are above the US as a guide to the trip point beneath which labour market conditions become inflationary, then you'd have to portray Canada's labour market as tighter than the US. This is shown in chart 3. Canada's NAIRU is usually judged to be higher than the US due to various drivers of structural unemployment.

Therefore, if the only thing that mattered was the labour market tightness angle, then the BoC should be hiking faster than the Fed. That has been among the underpinning points of why we had the BoC's terminal rate at 3%, above the Fed's 2.5% although we are likely to raise the latter in our upcoming forecast round.

This makes me skeptical toward real bond pricing of inflation breakevens that show the US higher than Canada. Canada underestimates CPI inflation by 1–2% in y/y terms and has tighter labour markets with worse productivity while it is importing a positive terms of trade shock that the US is not getting, yet the market judges inflation risk to be higher stateside (albeit with highly impure gauges).

GENERALLY SOLID DETAILS

Most of the details around the job tallies were pretty good.

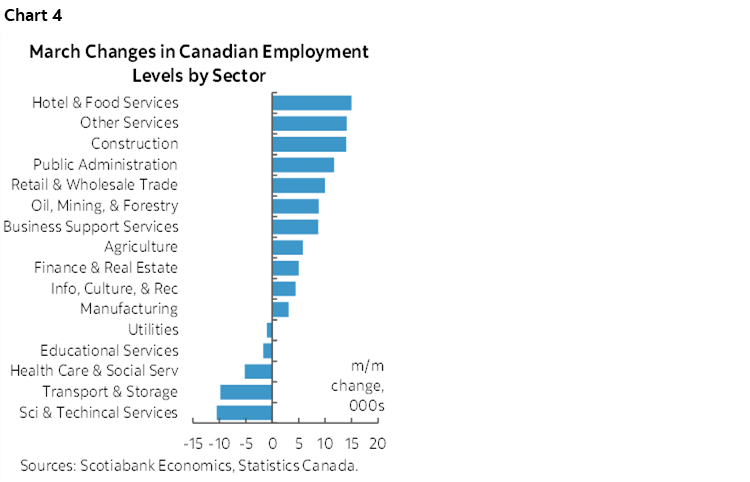

- breadth was led by construction (+14k), resources (+8.8k), accommodation and food services (+15k) and 'other" services (+14k) with retail/wholesale up 10k. That’s ok breadth, not spectacular breadth, and it indicates that it wasn’t just a job gain fed by the most distanced sectors like restaurants and hotels. See chart 4.

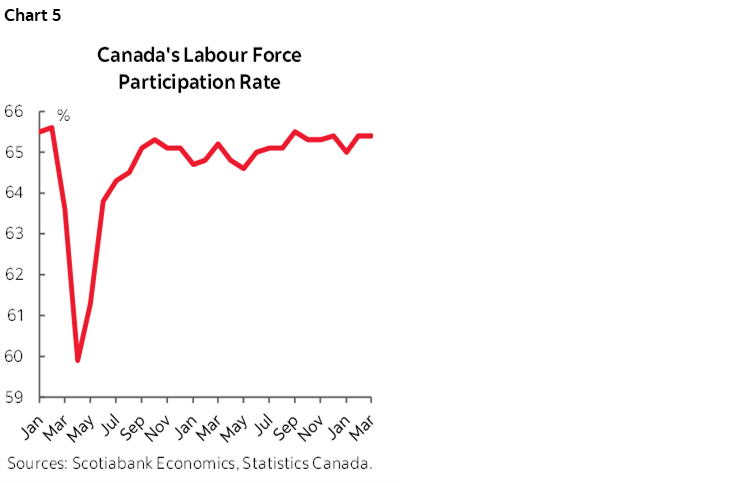

- The UR fell because job growth was about double the pace of increase in the size of the labour force (72.5k versus 37k). The labour force participation rate has fully recovered from the pandemic (chart 5).

- Hours worked were up by 1.3% m/m non-annualized after a 3.6% rise in February. Since GDP is an identity expressed as GDP times hours worked, the surge in hours worked is a very positive GDP signal. In fact, hours worked were up by 8.7% q/q SAAR in Q4, another 4.4% in Q1, and the hand-off effect from March suggests 8.3% q/q SAAR is baked into Q2 (chart 6). As a consequence, the BoC needs to update its Q1 GDP growth forecast from the January MPR that pegged it at about 2% to probably the 4–5% range and so growth is much stronger at the starting point for the year than their now stale forecasts anticipated. The baked-in momentum in hours worked going into Q2 may suggest that such growth momentum can continue.

- all of the job growth was in full-time employment (92.7k) as part-time jobs fell by 20.3k.

- Most of the job gain was in the 25+ age cohort (+56k) as youth jobs were up 17k.

- the gain was very lopsided toward adult men (50k) as adult women saw only +6k more jobs.

- private payrolls (+39k) and self-employed (+31k) drove the gain with public sector payroll jobs flat (+2k). Always treat the self-employed category skeptically given its softer data aspect versus payrolls.

- the regional breakdown basically says the job gain reflected a continued reopening effect. Ontario was up 35k, Quebec was up 27k and BC was up 10.5k. Ontario’s and Quebec’s gains were all in full-time jobs. BC was all in part-time jobs.

CAUTIONS — WAGES AND PRODUCTIVIITY

One negative took the form of another month of weak wages. Average hourly wages of permanent employees used to be the BoC’s preferred measure and it still benefits from being the most timely gauge of wage pressures. It was down 0.3% m/m at a seasonally adjusted and annualized rate. That’s tiny, but the month before saw a decline of -3.6% and so we’ve had a couple of months of softening after a string of about 6.0–8.5% m/m annualized gains since last July (chart 7). This is unlike the US that had a soft patch for wage growth in February and then rebounded in March.

It’s not clear to me why this is happening. One theory could be that jobs coming back may be lower paying high contact service jobs, but the composition of the job gains this month doesn’t lend much support to that average weighting argument. Further, we didn’t see this happen during the Delta closing and reopening periods, so why during Omicron?

THE JOB MARKET’S ACHILLEES HEEL

Even though it doesn't win popularity contests to speak about it, the cost to all of this is that productivity growth which is worsening. The GDP surge is still being driven by bodies and hours but unlike the US, Canada continues to face declining absolute levels of real GDP per hour worked (chart 8). It’s among the worst performances on this relative yardstick in history.

That’s important because most economists would argue that productivity is an important driver of longer run real wage growth. On average, wage gains above the cost of living pressures are more likely to be sustainable if workers are able to produce more output per hour worked than in the past. Poor productivity (falling!) is not a great harbinger of future living standards. That’s one reason why I didn’t like yesterday’s budget that—despite the political sloganeering—had nothing of substance to offer in terms of addressing the nation’s number one economic challenge which is the interplay between tanking productivity and soaring inflation. Failure to treat this seriously risks impairment of fiscal conditions in future.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.