- Job gains remain strong

- Canada may well be moving past full employment

- Wage growth continues to accelerate across multiple sectors

- Wage-driven cost-push inflation is bigger than the BoC admits

CDN jobs m/m 000s // unemployment rate %, SA, November:

Actual: 153.7 / 6.0

Scotia: 0.0 / 6.8

Consensus: 37.5 / 6.6

Prior: 31.2 / 6.7

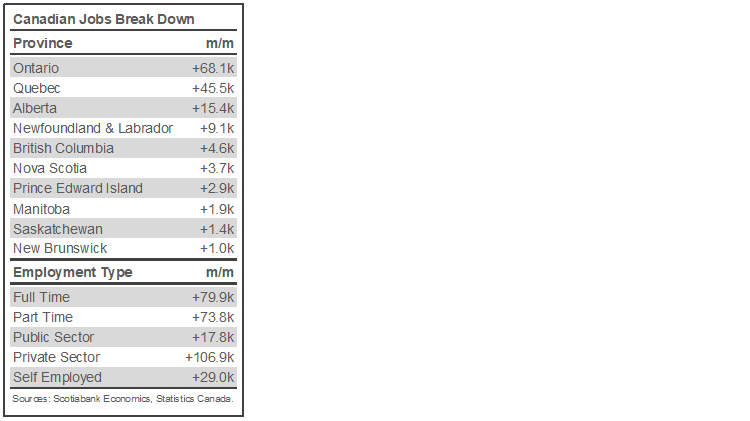

For all intents and purposes, Canada appears to be at full employment and may be moving beyond. Jobs crushed everyone's guesses again, growth in new entrants to the labour force has petered out and so wages are sharply accelerating. See a partial breakdown of the details behind the latest jobs blow-out in the accompanying table. CAD initially rallied by about three-quarters of a cent but is now little changed as the USD regained strength following US payrolls. Short-term Canadian yields spiked by ~10bs on BoC hike bets and have since held on to most of that initial reaction.

WAGES ARE SOARING...

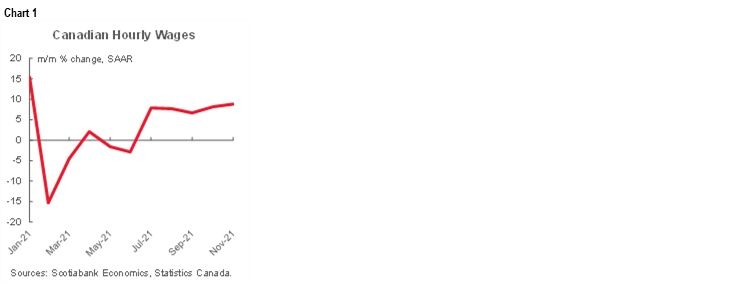

Let’s start with wages. Month-over-month annualized wage gains are off the chart (chart 1). Canada has been registering about 7–9% gains in average hourly wages of permanent workers every month since July. That’s five months of data showing a massive acceleration in wage pressures in what used to be the BoC’s preferred measure of wage growth. I’ve been referencing this figure for a long time now because it’s a better way to capture turns.

The year-over-year wage growth rate will do so much more slowly such that the memo on rising wages wouldn’t land in in-boxes until well into 2022 according to that measure. Worse is that it’s downright laughable to read StatCan explaining away wage growth by referencing it in two-year intervals (today’s versus the same period in 2019) in order to smooth out pandemic influences; by the time that measure changes, the BoC will get the memo in 2023!! Ottawa appears to have horse-blinders on toward basic wage data.

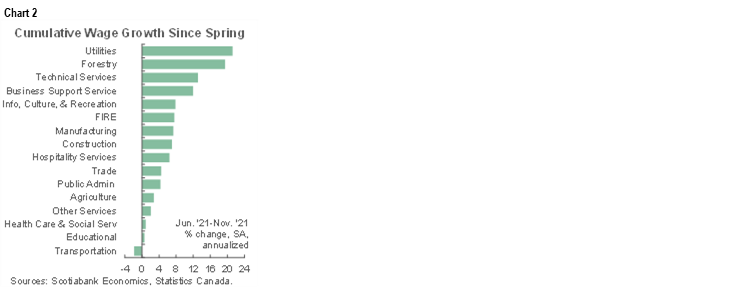

Worse is that some folks in Ottawa think all of this manna from heaven is going to a select few. Chart 2 shows that multiple sectors have been forced into paying considerably higher wages. The chart takes seasonally adjusted wages in each sector compared to June and annualizes the percentage gain since then in order to show what they’ve been faced with for almost half a year now. Wage pressures are widespread across sectors which itself is a further sign that broad economy-wide wage pressures are not just a compositional effect. Not realizing this can lead to fundamentally misguided monetary and broader public policies.

...AND SUCH WAGE PRESSURES COULD PERSIST...

It is still early in the debate with just five months of accelerating wage pressures to go by. With each passing month of evidence that wage growth is still strong, however, the argument that it’s just a reopening spurt gets weaker. Canada’s economy shut for a couple of months back in the Spring and here we have five months of pressures.

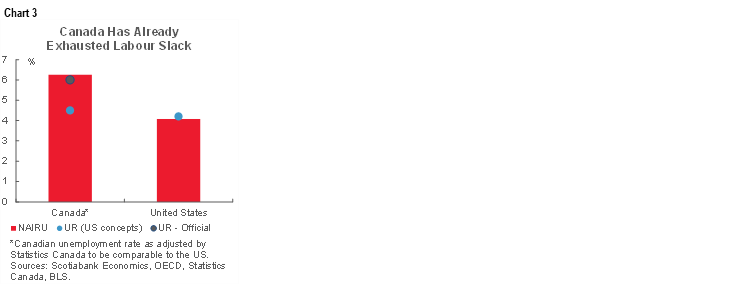

But could such pressures have legs? We’ll see, but it partly depends upon where maximum employment sits which is always highly uncertain. But the possibility that we are breaching the dyke on labour costs cannot be dismissed. Chart 3 compares Canada’s official unemployment rate and also Canada’s unemployment rate adjusted to US measurement concepts to the OECD’s guesstimate for NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment). NAIRU can proxy the point at which full employment is thought to exist. It’s a highly uncertain estimate, but if it’s in the right ballpark then Canada could be at or beyond maximum employment by this yardstick. Ultimately, it may be that perhaps prices are the best signal of what’s going on in a marketplace and in this case wage figures may be the most dispassionate arbiter of the debate over labour slack.

...AND THIS HAS ARGUABLY BEEN GOING ON FOR QUITE A WHILE

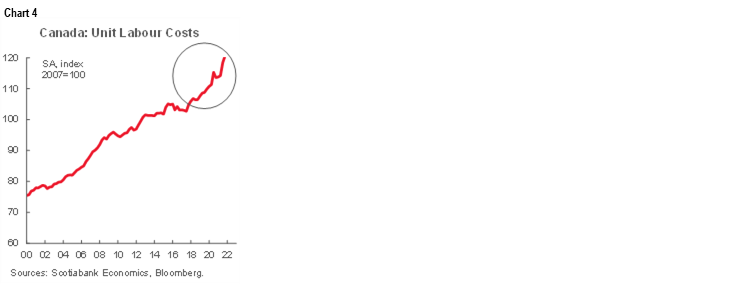

We also got an update on productivity-adjusted labour costs when StatCan updated unit labour costs to Q3 (chart 4). I had to adjust the scale to accommodate the acceleration! ULCs were up 7.7% q/q SAAR in Q3. Unit labour costs were relatively tame for many years coming out of the Global Financial Crisis. That started to change around 2017–18 when this yardstick began to rise more rapidly. It is now going vertical. When employment costs are far outstripping productivity growth it can tend to fan inflationary pressure.

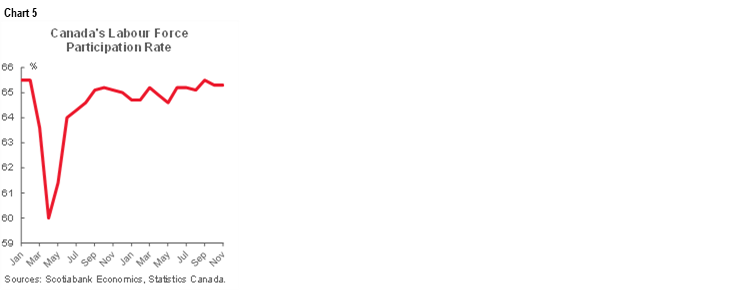

The fact that job growth is strong while wages are accelerating should also be coupled with the fact that growth in the labour force is comparatively mild. The labour force—defined as those seeking work who are both successful and unsuccessful at doing so—is only 1.4% y/y larger now while jobs are up by 4.2% or three times as fast over the past year. The labour force participation rate has for all practical purposes fully recovered (chart 5). Employers are finding it tougher to find new workers and being put into a position whereby they are increasingly having to pay ransom wages.

Immigration can help if it accelerates beyond converting folks who are already here into citizens and is targeted to the areas of skills shortages. So can improved confidence of potential workers to enter high contact jobs that are most vulnerable to the pandemic, but at a minimum that may be further delayed by Omicron. That leaves wages as the enticement, such that actual wages rise toward reservation wages in order to pull in more people from the sidelines. In the process, measures of job turnover, more job shifting and more mobility will continue to rise. These are positive signals for the labour market and economy, but present very tough circumstances for employers to navigate through in terms of whether to spend more on wages or more for job searches, training and disruptions to their businesses. With much of the emphasis during the pandemic having been placed upon helping workers, the policy pivot toward recognizing the pressures facing employers across multiple industries is long overdue.

OTHER DETAILS

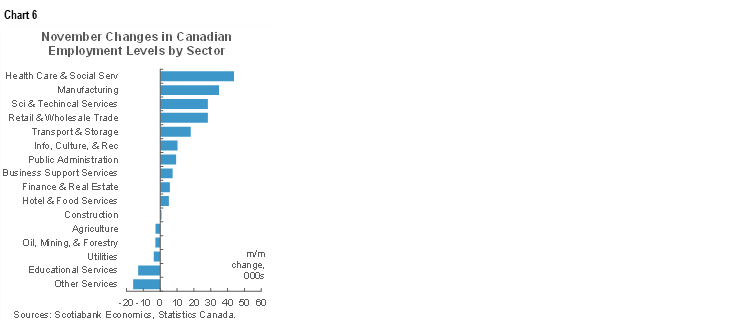

There was high breadth to the growth in employment. Services were up 127k with jobs in the goods sector up 26k. Within goods it was all manufacturing (+35k) with the rest little changed. Within services it was health & social assistance (+44k), followed by wholesale/retail (+28k) and prof/sci/tech (+28k), while transportation/warehousing jobs were up 18k. There were smaller gains elsewhere as summed up in chart 6. The main downsides were education (-13k) and 'other' services (-16k).

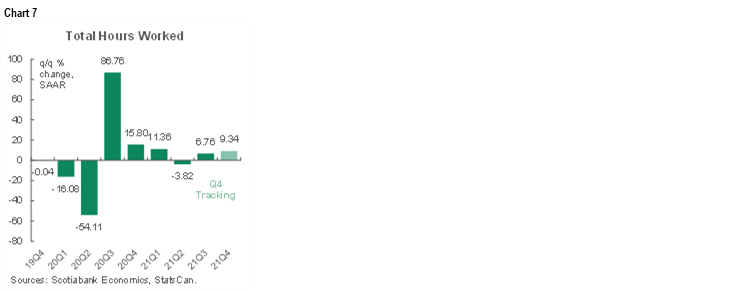

Hours worked were up 0.7% m/m SA in November. Canada has been registering powerful monthly gains during four of the past five months. Hours worked were up 6.8% q/q SAAR in Q3 and are now tracking an explosive 9.3% q/q rise in Q4 (chart 7). Since GDP is an identity defined as hours worked times labour productivity, the 9.3% Q4 rise points to very strong GDP growth. The caveat is again the fact that the reference week did not capture BC’s flooding that hit the following week but that’s unlikely to put a sizable dent in the nationwide tallies.

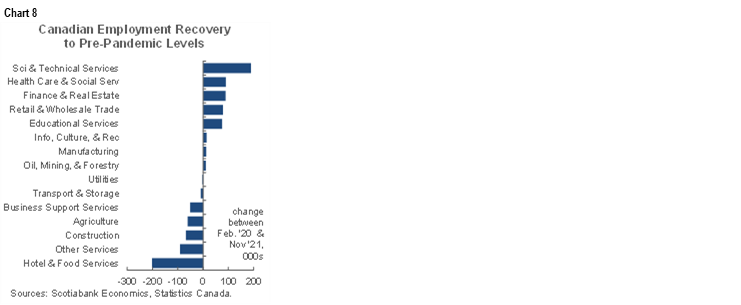

Chart 8 shows that the job full recovery is still uneven across sectors. In my opinion, that’s not something that should fuss monetary policy as a blunt instrument that targets broad outcomes overwhelmingly above modest feedback effects stemming from unequal outcomes. Training and support programs lie within the realm of fiscal policy makers. To blur the lines—say by adjusting the Bank of Canada’s inflation mandate toward job market targets—risks backfiring at the worst moment given evidence of full employment.

Statcan flipped the survey reference week this time. It's usually the week within the month that includes the 15th day. This time it was the week of the 7th–13th which was before BC's flooding and there is no explanation for why. BC’s flooding hit the following week. BC only accounted for +5k jobs last month in this report. Pretty much all of the gain was in Ontario and Quebec. Hours worked are more likely to have suffered in BC, but is it possible the flood effect will never surface in the data? If the December reference week goes back to being the week including the 15th and they base m/m changes off of the earlier than usual reference week for November, then maybe BC’s hours worked and any jobs hit may have significantly recovered by that time. Presto, never happened—according to the statisticians anyway….

In any event, BC’s flooding shouldn’t influence the BoC’s thinking. The standard playbook is to knock back the current impact on Q4 and punt the recovery into the next period. Monetary policy would look through that and we don’t know the longer-term damage to the capital stock.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.