- Job growth exceeded expectations with strong details

- The gain in labour force participation is back to pre-pandemic levels

- Wage growth decelerated...

- ...but trend gains continue to outpace poor productivity

- The BoC is forecast to hike 25bps next week with a hawkish bias

- Canada jobs m/m 000s // UR %, June:

- Actual: 60 / 5.4

- Scotia: 40 / 5.3

- Consensus: 20 / 5.3

- Prior: -17.3 / 5.2

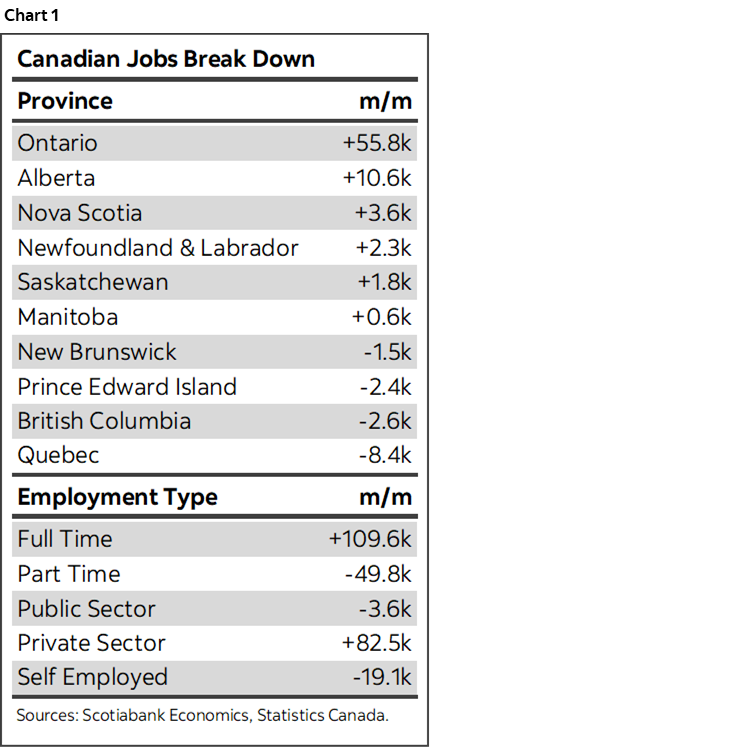

Canada’s jobs report offered enough to support my pre-existing call for a further Bank of Canada hike next week in the context of the full suite of evidence to date and a fuller preview will be offered in the Global Week Ahead later today. The details behind the impressive 60k gain in employment were robust and mildly dented by cooler wage growth following a strong prior month. Job growth exceeded consensus and my estimate that was nevertheless the second highest out there. Chart 1 provides several highlights.

The market reaction was somewhat dented by the softer than expected US payrolls figure albeit with stronger US wage growth, but Canada’s shorter term yields rose a touch in absolute terms and more so in relation to a mild rally in US 2s. The C$ strengthened by nearly three-quarters of a cent so far. Market pricing for next week’s BoC decision edged up by 2–3bps to make it considerably better than even odds being priced for a hike.

My fear into these numbers had been that the only driver of a rebound in job growth after losing 17k jobs in May would be a reversal of temporary distortions while the rest of the report would be weak. Instead, there was much more underlying strength to the hiring activity that continues to signal that the labour market remains very strong and very tight.

Youth employment rebounded with a gain of 30k that reverses the 77k drop the prior month such that perhaps it’s not as bad of a summer job market as it appeared to be in May. But it’s not just youths that benefited here, as the 25+ age bracket also gained 30k jobs and this time entirely men.

Self-employed jobs fell another 19k to add to the 40k drop the prior month and so there was no stabilization effect here, but it was offset by a 79k surge in payroll jobs. Better yet, the torrent of public sector hiring since the start of the pandemic wasn’t the prime factor for once, as private sector payrolls led the gains with a jump of 83k albeit with another 7k public administration jobs. The wealth creating part of the economy generally stepped up to the plate as the core driver.

All of the 60k additional jobs in June were in full-time positions (+110k) as part-time jobs fell by 50k and this adds to the quality of the readings.

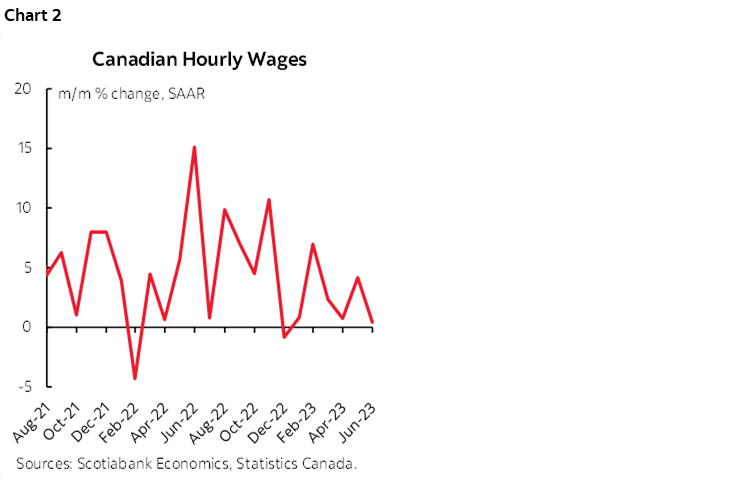

Wages were up by just 0.4% m/m at a seasonally adjusted and annualized pace in June which was disappointing but recognize that this came on the heels of the strong 4.2% m/m SAAR gain the prior month. A high jumping-off effect made another strong gain difficult to achieve. Instead, focus upon the smoothed trend in chart 2. Gains have been trending in the roughly 2–3% range this year with some lumpy jumps along the way like May’s 4.2% and February’s 7%. The effects of big unionized wage gains upon average wage growth still lie ahead. Furthermore, any wage gains with poor productivity since the start of the pandemic are contributing to inflationary pressures at the margin.

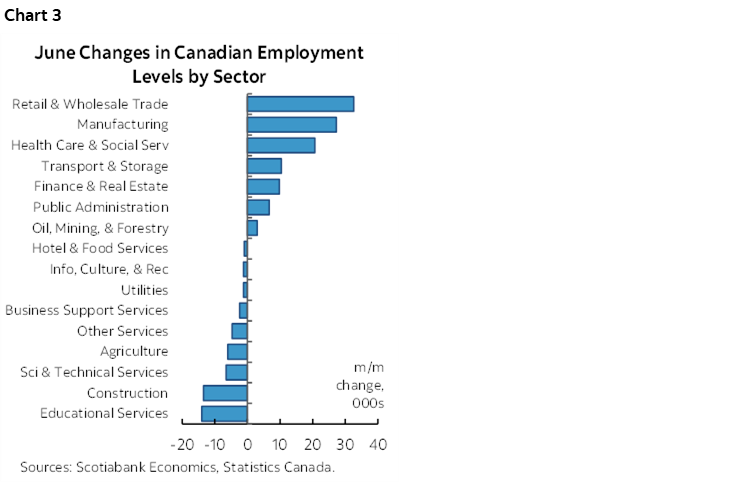

By sector (chart 3), services led the way with a 50k gain followed by a 10k gain in goods producing sectors’ employment. Within goods, the gain was in manufacturing (+27k) as construction fell 14k while resources, utilities and agriculture were all little changed.

Within services, the gain was driven by a few sectors led by wholesale and retail trade (+33k), followed by health care and social assistance (+21k), and then 10k gains in each of the transportation/warehousing and FIRE sectors.

By province, most of the gain was in Ontario (+56k) followed by Alberta (11k) as other provinces were mostly flat and only Quebec posted a modest 8k drop.

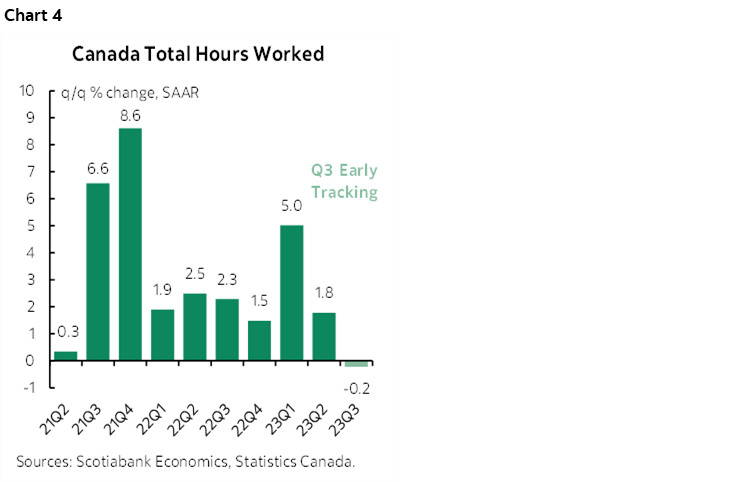

Hours worked were a plus for GDP growth given that GDP is an identity defined as hours worked times labour productivity (itself defined as inflation-adjusted output per hour worked). Hours were up by 0.1% m/m in June and were up by 1.8% q/q SAAR in Q2 (chart 4). While we don’t have any Q3 data, there is no growth in hours baked into Q3 based solely upon the way the quarter exited and the Q2 average. To get growth in Q3 will rest entirely upon monthly updates from July through September absent any momentum effect.

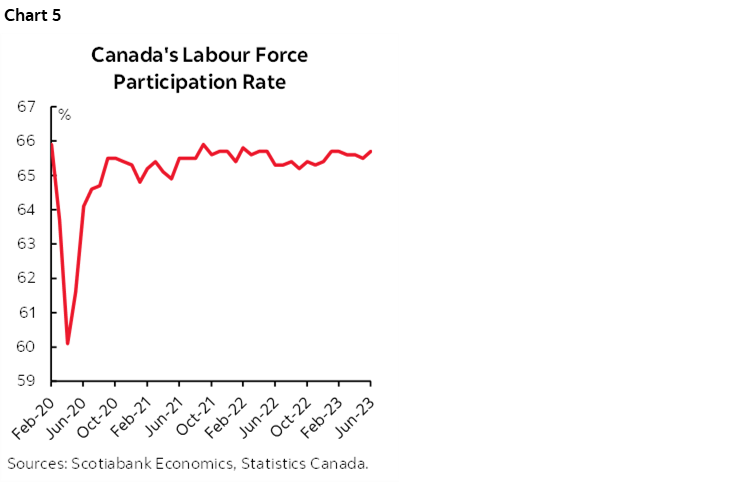

The unemployment rate edged up two-tenths to 5.4% despite the solid gain in jobs because more people entered the workforce in search of jobs than got them. The labour force expanded by 114k last month and not just due to population growth because the labour force participation rate moved up two-tenths to 65.7% (chart 5) which somewhat leans against interpreting the expansion of the pool of available labour as having been driven by immigration as opposed to expanded labour force entry by the existing population. That signals a labour market that is still able to take in new entrants and the participation rate is almost dead even with where it was before the pandemic struck. Perhaps the labour pool is expanding out of necessity as households adjust to various pressures. Most of the rise of the labour force was in Ontario (+69k) with smaller gains in BC, Alberta and Quebec. By age category, there were 62k more youths 15–24 searching for work and 52k more folks aged 25+ looking for work.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.