A BEST-BEFORE DATE ON FISCAL WINDFALLS

- Canadians will get a peek at how federal finances are holding up against mounting economic headwinds this Thursday when the Fall Economic and Fiscal Update is tabled.

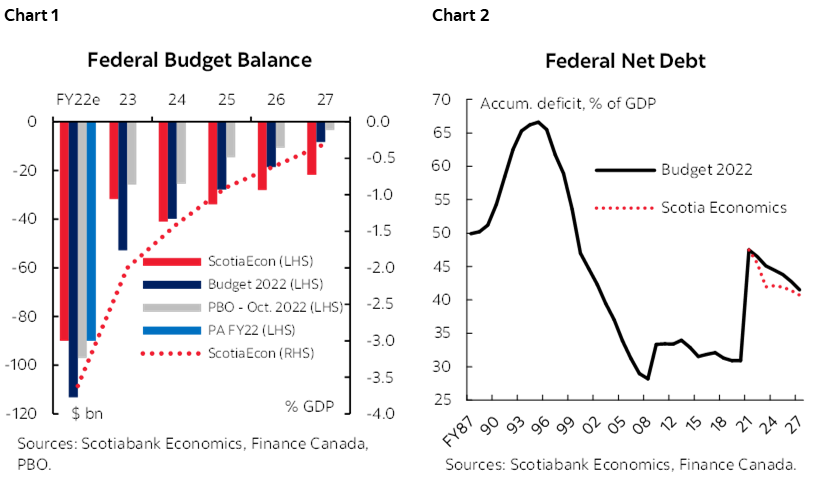

- In the near-term, large government revenue windfalls should drive materially tighter deficits relative to earlier expectations at budget time—in the order of $45 bn between FY22–FY23 alone. But these drivers are likely to wane over the horizon as the economy slows (chart 1).

- Recent fiscal and economic developments should drive a step-change improvement in federal debt (to around 42% of GDP in FY23), but improvements thereafter will likely be hard-won (chart 2).

- Elevated recession risk—potentially compounded by policy missteps—is likely top-of-mind for the Finance Minister as she crafts this Update. We expect a cautious tone that largely holds the line on major new spending as the Canadian economy braces for landing, while laying the groundwork for a growth agenda in Budget 2023.

- The Minister already modestly loosened the purse strings earlier this Fall with $4.5 bn in targeted affordability measures. Together with provinces, Canadian households should see about 1% of GDP flowing over the coming quarters.

- The federal government will still be able to claim favourable debt levels and trajectories relative to most peers, but it should have less confidence around how much headroom this imparts. Elevated inflation and uncertain interest rate paths have markets on edge.

- The Update is wedged between Wednesday’s US Federal Reserve FOMC rate decision and Friday’s job report here in Canada. Absent any spending surprises on Thursday, its impacts should be more or less obscured by positioning against these other potential market-movers.

- The Minister would be right to hold the line.

WHAT TO EXPECT (AND WHAT NOT TO EXPECT)

The federal Fall Economic and Fiscal Update should deliver a largely stay-the-course policy plan. Mini-stimulus was tabled earlier this Fall to the tune of $4.5 bn, while the Finance Minister has signaled restraint. The bottom line should look substantially better in the near-term owing to incredibly strong revenue performance in recent quarters, but a slowing economy is likely to put upward pressure on the balance over the medium term. Near-term revenue lifts should also drive a material step-change improvement in federal net debt in FY23, then resume its gradual descent thereafter. Here are a few things we will be watching for on Thursday.

Just how much better does the bottom line look? Probably substantially better in the near term. Public Accounts, tabled on October 27th showed last year’s deficit (FY22 ending March 31, 2022) came in well-under April’s forecasts at $90 bn (3.7% of GDP) for a $24 bn improvement relative to expectations in Budget 2022. (It looks even better at $80 bn once actuarial charges that have no bearing on the fiscal stance in economic terms are netted out.) Tax revenue windfalls drove these gains with personal and corporate income taxes contributing hefty shares, while expenditures more or less came in on the mark.

This revenue momentum should continue through the current fiscal year. The balance, in fact, stood modestly in surplus at the end of August with very strong revenue growth (19% y/y) and a commensurate contraction in expenditures (-19% y/y). Most of this reflects rebound and program roll-off effects, along with a lift from elevated commodity prices, so do not expect that pace to continue. Government expenditure disbursements also tend to be skewed to the fiscal year-end. Nevertheless, decent revenue momentum should continue over the course of this fiscal year, at least, despite economic output that is likely to move sideways for a couple of quarters. With assumptions of softening labour markets (i.e., not cratering), strengthening wages, and a lag to cooling corporate profitability, the deficit could land in the order of $32 bn (2.0% of GDP) in FY23 (versus the $53 bn shortfall envisioned in Budget 2022).

Beyond that, it is a bit of a mug’s game. We expect more pressure on the bottom line in FY24 as the effects of a cooling economy catch up. A combination of weaker revenues and higher automatic stabilizers is likely to add to the deficit. However, the very strong handoff from FY23 (and FY22) should drive base effects that mostly offset renewed fiscal pressures. Consequently, our best guess is that the deficit profile in outer years looks similar to the one presented in Budget 2022 despite very large deviations across a host of economic assumptions (table 1 & 2).

The deficit trajectory should continue to contract modestly to near-balance over the horizon. This would reflect a period of flat economic growth (or even a technical recession) against an aggressive rate tightening cycle, and—importantly, no further shocks (policy, economic, geopolitical) in the global economy that could tilt the world into a deeper recession and drag Canada with it. It would also reflect no major new discretionary spending by the federal government (or provinces) which could drive rates higher, growth lower, and balances larger. Obviously, these assumptions underpinning our baseline embed enormous uncertainties.

What would this do to debt levels? Debt levels should look better, but not back to pre-pandemic levels. Near-term improvements to the fiscal balance along with stronger nominal GDP should drive a sharp drop in federal debt as a share of GDP. Public Accounts puts federal net debt (accumulated deficit) closer to 45.5% (versus 46.5% at budget time), while that hand-off along with continued improvements to the bottom line could bring it down to around 42% in FY23 (3 ppts lower relative to the Budget 2022 outlook). It should then trend modestly downward, contingent on the same wide-ranging assumptions around the deficit profile.

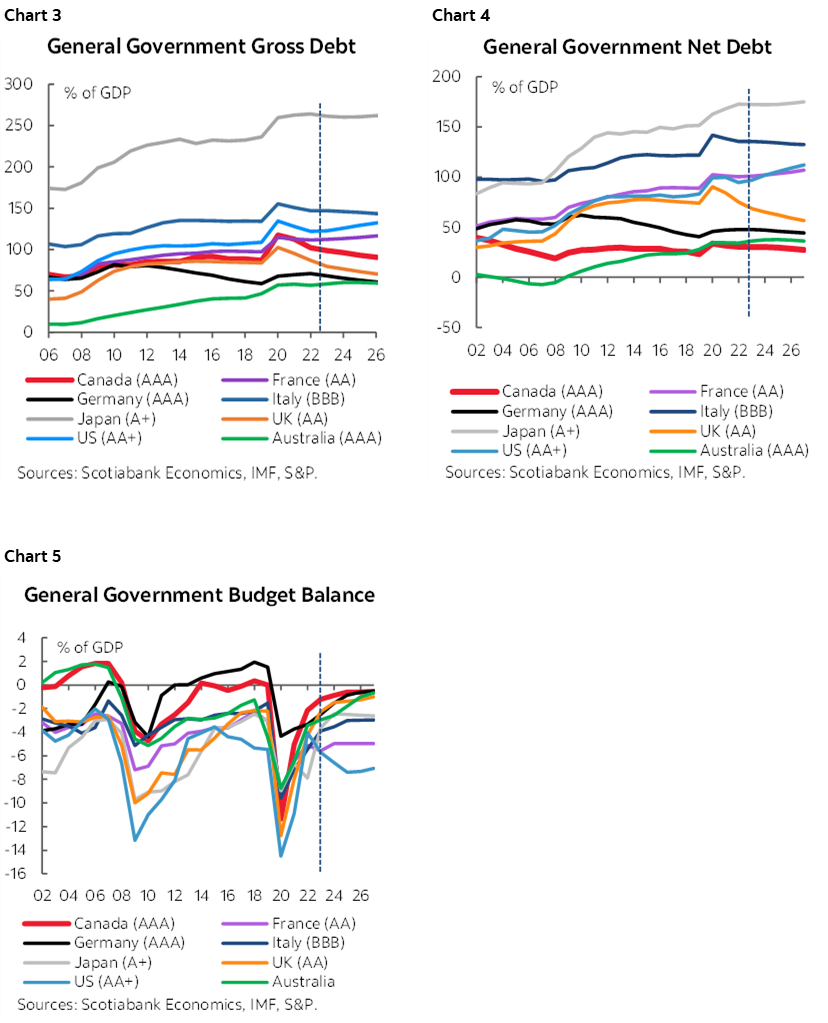

This would still be above pre-pandemic levels when federal net debt stood just above 30% of GDP, but it should still trend in the right direction. Canada’s general government (federal and provincial) debt advantage is widening slightly, particularly as weaker growth in other parts of the world drives fiscal deterioration (charts 3–5). Nevertheless, Canada’s lack of reserve currency status puts a lower tolerance on debt levels that limits the usefulness of such comparisons, while gross debt arguably matters more in times of market (and potential liquidity) stress.

Despite biannual calls for a fiscal anchor, we don’t expect to see any new ones in the Update. Modestly declining debt as a share of GDP with a crisis escape clause is likely to remain the soft tether. Debt service charges are starting to tick back up, but are still low on a historic basis (and in book-keeping terms are offset by lower actuarial valuations for government pension liabilities as a result of higher interest rates). Earlier efforts to term out debt provide some buffer to higher-than-anticipated interest rates.

What’s new? What’s not? We don’t expect there will be major new spending measures announced this week. Minister Freeland has signaled as much on the stimulus side in the lead-up. She’s cautioned in a recent speech that affordability pressures will continue to pinch many pocketbooks, but that the government can no longer “support every single Canadian in the way we did with the emergency measures” acknowledging the risk to inflation and interest rates. The Update is likely to play up the $4.5 bn ($3.1 bn new) in measures announced earlier this Fall under the Cost of Living Act (a time-limited doubling of the GST credit, a one-time payment for renters, and a dental benefit, all income tested), on top of a much longer list of relief measures announced in Budget 2022. She would also be cognisant that recent affordability measures, combined with provinces, likely impart a $20 bn+ impulse to Canadian households over the next several quarters.

Minister Freeland is clearly laying the ground for a (re-)new(ed) growth agenda, and this language will likely feature in the Update. Again in recent speeches, she has acknowledged the need for a more strategic approach—or for a “muscular industrial policy”—to tackle dismal productivity. She points to the US Inflation Reduction Act as a sign of a new world order involving “friend-shoring” and strategic alliances, while also cautioning against threats to Canada’s own competitiveness. This government has made a series of commitments to this end including electric vehicle investments, a critical minerals strategy, a Net Zero Accelerator, the Canada Growth Fund, as well as major investments in carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS). These are positive developments, but still fall short of a cohesive growth agenda (and execution is mostly still pending). We expect a new growth agenda will mostly be a Budget 2023 story (and potentially be backed with more dollars at that time).

With a bias toward modestly expansionary fiscal policy that pre-dates the pandemic, there is likely upside risk to additional spending. This is on our radar, but not in our baseline for this Update. Recent announcements on dental care likely buy some time with the NDP before confronting bigger pledges under the Supply Agreement towards pharmacare (costed at $11 bn/yr once fully operational by the PBO). Provincial Premiers are also not likely to see their demand for a $28 bn riser on the health transfer addressed anytime soon despite ramped-up public campaigns by the Council of the Federation. Parliament is also close to passing a new disability benefit that could be material when details are revealed. Specifics of an expanded Employment Insurance program are still pending, including how premiums would be financed. Last but not least, Canada still needs to massively scale-up net zero investments. Budget 2022 noted that annual investments by the public and private sectors combined would need to rise from $15–25 bn (in 2020) to $125–140 bn by 2050 with governments shouldering about a third of this. To be clear, we don’t expect major new spending in these areas to be unleashed this week, but we are keeping them on our radar.

How will markets react? A tighter budget balance projected for FY23 in the order of $20 bn would take out some supply at the margin—which in theory should drive lower yields— but in the current market context other drivers are likely to dominate (and there is still another budget before fiscal year-end).

The Bank of Canada’s dovish shift last week could heighten sensitivity to policy risk on the fiscal side. Namely, if Minister Freeland strays from our expectations of a slim update, this could lead to a (re-)pricing of higher rates ahead for the Bank. Market proxies are still pricing in higher rates for the US despite a host of potential arguments against this and it is feeding across the curve (charts 6 & 7). A convergence of relative central government fiscal positions (chart 8) could narrow gaps in the rate complex for the wrong (economic) reasons.

Against a backdrop of elevated interest rates and intertwined policy and recession risk clouding the outlook ahead, the Finance Minister may not want to test markets with an Update even perceived to tilt the boat. In that case, effects of this Update are likely short-lived at best, but more likely swamped by re– and/or pre-positioning with a US Fed rate decision on Wednesday and a Canadian jobs report on Friday.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.