SNOWBALL SPENDING HARD TO STOP

- Canadians will get a fresh look at the state of federal finances when Canadian Finance Minister Freeland tables the Fall Economic & Fiscal Update on November 21st.

- This should be a relatively slim update. Slowing economic activity foreshadows waning revenue windfalls ahead, in turn, curbing an important funding source for past spending sprees.

- We would guess another $20 bn (0.8% of GDP) could be folded into the 5-year fiscal outlook, mostly reflecting previously announced EV and battery chain investments, as well as the GST waiver for rental housing.

- The stronger fiscal hand-off from FY23 is likely offset by a sharper contraction in FY24 than envisioned at budget time last March. The update will likely table higher debt charges, but actuarial offsets would partially shield impacts on the bottom line.

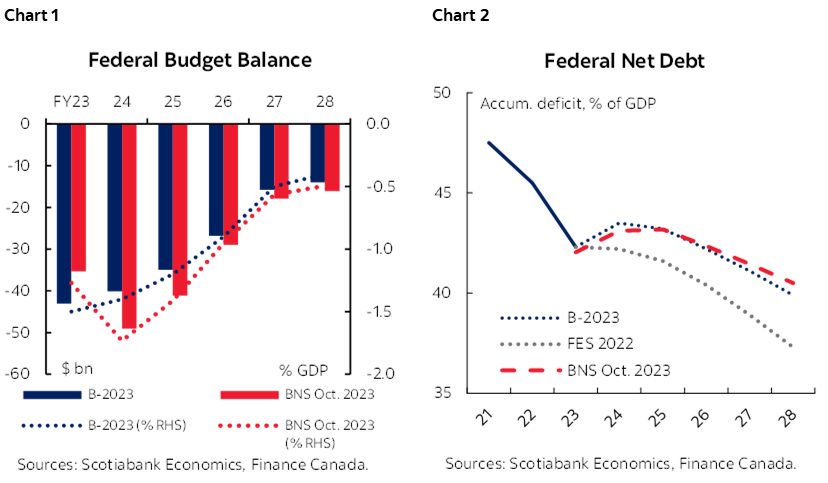

- The net effect of these anticipated developments would leave the fiscal trajectory—for deficits and debt—only marginally higher over the horizon (charts 1 & 2).

- The Minister is likely to continue preaching fiscal restraint. This has come to mean keeping debt as a share of the economy on a downward path over the medium term with an increasing emphasis on the ‘medium term’.

- It’s a toss-up if that debt peak gets pushed out another year in this update. While it would mostly be incrementally irrelevant (the horse has already left the barn), it would further erode credibility in this loose fiscal anchor.

- At this juncture, the least-worse option for the Minister would be to do nothing. Inflation persistence and uncertainty warrant such a pause.

- She’ll be delivering the update into the after-hours of the latest CPI print. Markets will be keenly focused on hard evidence that core inflation is slowing durably. Absent those comforts earlier in the day, she risks tilting markets towards pricing another hike on the horizon.

- Admittedly, market attention span can be short—exogenous developments are mostly carrying the day, while Canada’s fiscal activism is already baked into the system and its relative debt advantage is still largely intact—but Canadians would feel the pain of yet another rate hike.

IT’S THE ECONOMY, STUPID

Canada’s federal Finance Minister will deliver another fiscal update in an environment of persistent uncertainty, volatility, and ever-evolving developments. From tragic conflict in the Middle East to persistent inflation and elevated interest rates, the economic outlook remains fraught with risk. Nevertheless, nominal output is closely tracking private sector expectations at the time of Budget 2023 despite interest rates sitting markedly higher than forecast last March (table 1).

Resilience has so far beat out recession rhetoric. This holds not only on the economic front, but also fiscally. Job growth has slowed—but it’s still growing—and wage pressures have proven robust. This is padding government coffers with almost half of budgetary revenues coming from people’s paychecks. Recently-tabled Public Accounts posted an $8 bn improvement in the FY23 bottom line on the back of a $10 bn revenue windfall. (Notably, the government also recorded $26 bn related to Indigenous claims, absent which, the shortfall would have stood at just $9 bn versus the recorded $35 bn deficit.)

The economy is nevertheless slowing by design (and out of necessity) and, with it, fiscal tailwinds. Our latest outlook pencils in relatively flat economic activity for at least the remainder of this current fiscal year (FY24). With core inflation metrics still stubbornly elevated, the Bank of Canada is likely to maintain its overnight rate at its current 5% with the balance of risk titled to potentially more. Hence, the Governor’s understated plea last month that “it would be helpful if monetary and fiscal policy was rowing in the same direction.”

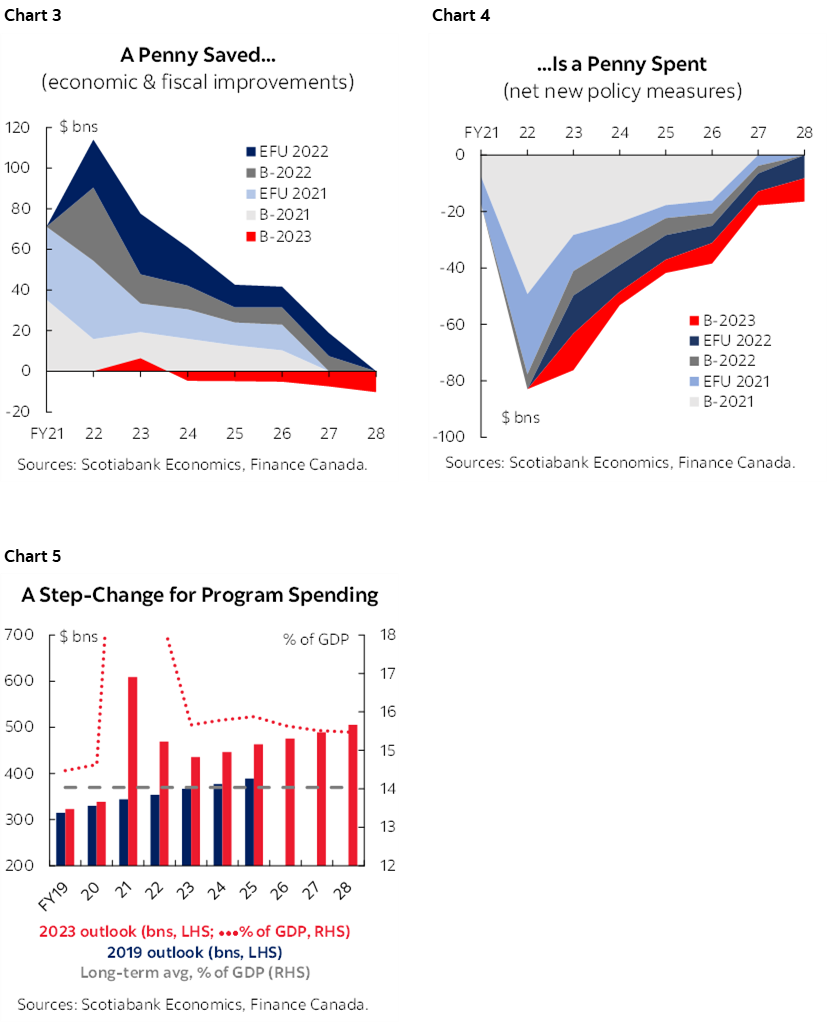

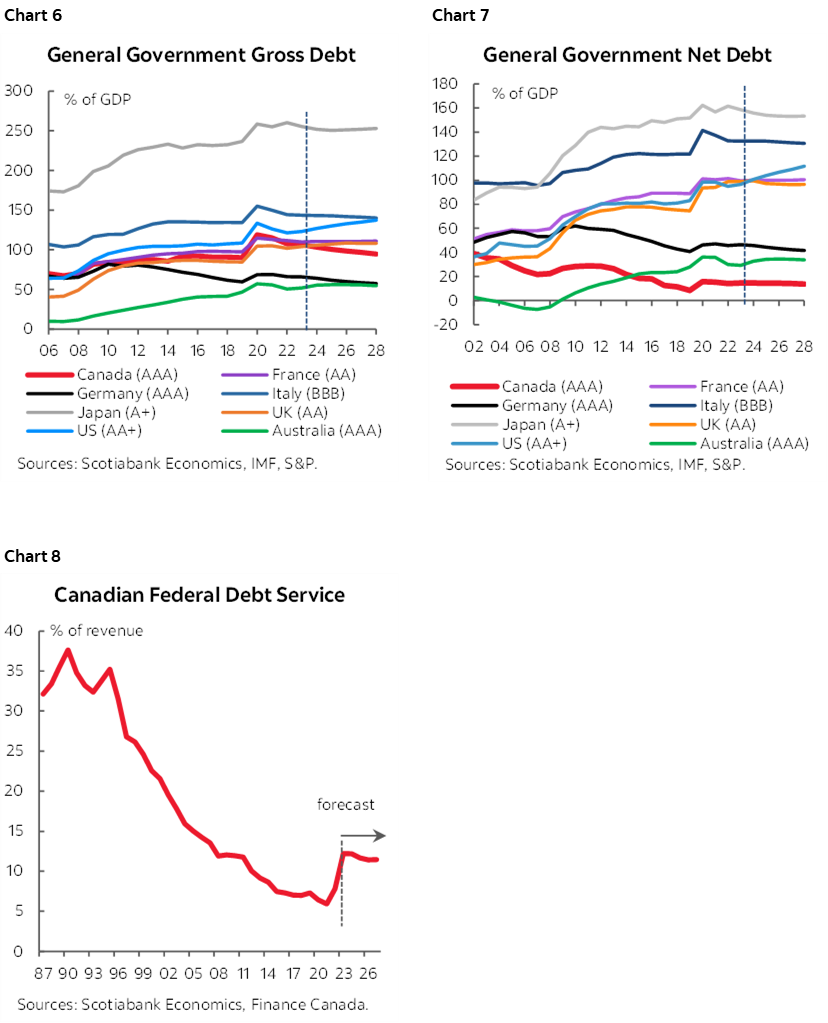

The federal finance minister would be wise to heed this call for a truce, even if she is unlikely able to radically pivot at this point. All levels of government have persistently, if not predictably, rolled out ‘modest’ new measures over the past two years that have cumulatively snowballed into something more substantive. Starting with the 2021 budget-of-a-lifetime, the federal government alone has tabled a cumulative $345 bn in net new measures, largely offset by more favourable economic conditions that delivered an estimated $400 bn in improvements over the rolling planning horizon (charts 3 & 4). Stronger economic momentum has not obscured a step-change in program spending over the timeframe, putting all the more pressure on revenues down the road (chart 5).

Structural shifts aside, the risk of further stoking near-term demand looms large. Despite the ensuing slowdown, the economy is still deemed to sit in excess demand. Lagged effects of interest rates should continue to narrow the output gap, but there is a high degree of uncertainty around embedded assumptions. The Bank of Canada’s next decisions will necessarily hinge on the projected inflation path ahead even if distributional impacts would hit lower income households harder.

The system is already well-primed. This past summer alone Canadian households received another $3.25 bn injection (the grocery rebate and prepayments of the Canada Worker Benefit) from Ottawa. Meanwhile, provincial counterparts in central Canada have recently announced more to come with another billion before fiscal-year end between extension of the gas and fuel tax cuts in Ontario and the benefits indexation in Quebec.

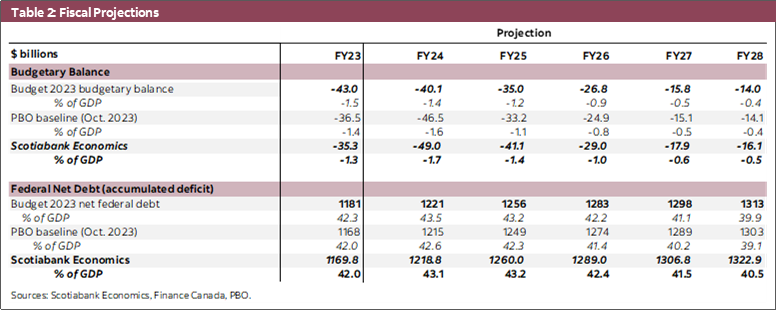

It is a red-herring to roll out fiscal sustainability arguments—for or against more spending—at this precarious juncture. It is one thing to have the fiscal space; it is another matter whether to use it. Canada’s government debt—general or federal, net or gross—is pretty good and its deficits relatively small plotted against peers (charts 6 & 7). Recently elevated interest rates further out on the yield curve should displace some of the complacency in the system about running persistent deficits, but these, if anything, are as much a political risk as a fiscal one at this point (chart 8). (Long-dated bond yields are likely to settle higher than pre-pandemic neutrals, but not at runaway levels.)

These are reasonable questions to ponder over the medium term, but the immediate risks should take precedent. Even the government’s own efforts to reverse and redirect waning productive investments in the Canadian economy towards laudable priorities like housing affordability and the green transition are undercut by tighter financial conditions. A fiscal stance that further elevates the risk of even-higher-for-longer interest rates and, in turn, the potential for a hard(er) landing is not a gamble the federal government should take right now.

IT’S POLITICS, DUH

What the Minister might do as an elected official is another matter. The minority government is two years old now, the Liberal party is waning in the polls, and its spending alliance with the NDP still has some boxes to tick. Markets haven’t punished modest deficits yet (though they have likely registered other interventionist, distortionary, or dysfunctional developments across the country). Meanwhile, many Canadians (including some Premiers!) put the blame on the Bank of Canada for the financial strains Canadians are feeling.

This suggests a stay-the-course fiscal refresh with an expansionary bias. The Minister has indicated the update will focus on housing and affordability measures within a “fiscally responsible framework”. In the months ahead of the update, major new EV and battery investments had been announced (with the federal 10-year commitment in the order of $19 bn), along with the waiver of the goods and services tax on new rental housing construction (we put a $250 mn annual placeholder here without strong conviction).

There would likely be a few more add-ons. The last few fiscal updates have tacked on a couple of billion one-offs (the grocery rebate, GST rebate, Canada Housing Benefit top-up, Canada Worker Benefit enhancement). Possibilities include the recently-legislated Canada Disability Benefit (we earlier costed this at several billion), or perhaps a phased-in approach to the long-awaited EI reform (read, expansion). Either of these could provide cover for the likely absence of the promised universal pharmacare program (with annual costs reaching $11 bn). It is neither in the Liberals’ nor the NDP’s interest to trigger a vote of confidence at this time.

Further actions to lift Canada’s productivity and competitiveness are still warranted over the medium term, but there is not likely (or should not likely be) much in the offing in the near-term. From Budget 2021 onward, the federal government has pledged well-over a hundred billion towards the green transition, but execution still remains largely over the horizon. Furthermore, the government’s surgical approach to (multi) program-design could prove its Achilles’ heel in a rapidly evolving environment where capital is highly mobile.

IT’S MARKETS, HUH?

This order of magnitude of anticipated spending would likely be a rounding error against other developments. While early months of FY24 suggest largely sideways movement for government revenues consistent with a slowing economy, a stronger hand-off from FY23 likely obscures some of the trend impacts on deficit and debt profiles relative to the outlook at budget time (table 2). We do think there is some potential upside for revenues over the medium term given structural changes in the labour force, but it is likely premature to book these just yet.

The more informative lines for market supply could come from off-budget items. The update should shed some light on the accounting treatment for the winding-down of the $50 bn Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) loan program (including bringing the riskier ones directly onto government books). There is also a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the future of Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMBs). The federal government had launched consultations last Spring around folding this $40 bn annual issuance into its regular Government of Canada (GoC) borrowing program. Since then, it announced a $20 bn CMB issuance increase in support of low-cost housing finance. While Budget 2023 had promised more clarity by Fall, it is not clear they are ready.

Refinancing and balance sheet run-offs at home and abroad are further overwhelming federal fiscal developments at the margin. Just for perspective, the federal government’s refinancing needs next (calendar year) amount to around $156 bn. The Bank of Canada’s balance sheet run-off is anticipated at around $55 bn over this same period. These numbers are an order-of-magnitude greater south of the border, against a larger and deteriorating deficit profile.

Further clouding the picture, there is still uncertainty around the new normal for long bond resting rates. The Government of Canada 10-year benchmark, for example, sat above 4% (and US 10-year Treasuries flirting with 5%) for a good part of the Fall. Though they have fallen back since, they are still well-above pre-pandemic levels and there is little consensus on drivers (from growing supply to inflation persistence to higher term premia). The government’s approach to terming out federal debt earlier in the pandemic buys it more time to see where things settle, but Canada is largely a price taker in this environment.

All the more reason to sit this one out. Exogenous factors could carry more punches yet.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.