Next Week's Risk Dashboard

- Will the BoC cut or hold? The cases for both & expectations

- ECB expected to begin easing—but should it?

- Will Canada’s jobs boom continue?

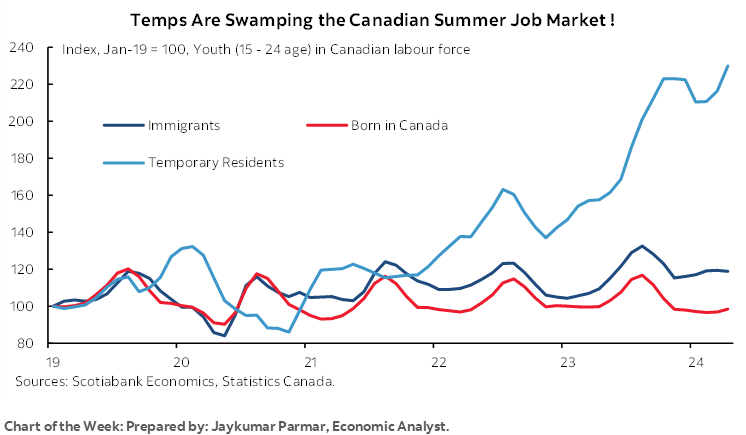

- Temps are swamping the Canadian summer job market

- US payrolls may be looking a tad Canadian

- Mexico’s election primer

- RBI expected to hold

- OPEC+ meeting probably won’t rock the boat

- Global macro

Chart of the Week

Major developments beckon this week that could inform broad global and regional macro risks. To date, none of the world’s most powerful central banks have begun easing policy. Several central banks have already been cutting and for some time across places such as Latin America, Switzerland, and Sweden, but this week might kick it up a few notches with the ECB most likely to lead the charge.

The Bank of Canada’s decision is much more uncertain. It could go either way. I’ve laid out the case for going now, the case for waiting, and what I think will happen. If Macklem is at all true to his word, then this week seems too soon and it should be too soon to cut.

Top tier data will include US payrolls and Canadian jobs. Policy risk may be front and center in Mexico’s election outcome and the OPEC+ decision. Throughout it all there will be relatively lower risk in macro releases and expected holds by the RBI and Russia.

BANK OF CANADA—GUIDANCE MATTERS!

On Wednesday at 9:45amET the Bank of Canada will release its customary policy statement. Governor Macklem and Senior Deputy Governor Rogers will host the customary press conference forty-five minutes later. There will be no Monetary Policy Report with this one as the next full forecast update will be offered with the July 24th decision.

Each of June, July and September are live meetings for a first cut by the BoC. Markets are partly priced for a 25bps cut at this meeting and fully priced for a cut at the July meeting and a tiny part of another. September is priced for about 40bps of cumulative easing by then. Consensus is divided with a modest majority expecting a cut at this coming meeting.

We forecast a hold and put higher odds on a cut in July—or later. Sooner and bigger cuts face higher risk of becoming policy error. There is nothing to gain from rushing into a cut at this meeting. There is much to be gained by a more complete assessment in July.

What follows will attempt to lay out both cases. In our view, the evidence leans more closely toward requiring more patience.

The Case for a Cut Now

There are five broad points in favour of cutting at this meeting.

- Canada has posted four months of lower core inflation. Trimmed mean and weighted median CPI have been running at a one-handled month-over-month pace in seasonally adjusted terms at an annualized rate (chart 1). Some argue that this is evidence the BoC needs to begin easing right away because they believe this softening will prove to be persistent.

- From a risk management standpoint, if the inflation risks are thought to be coming back into better balance, then it may make sense to commence easing while admitting that the path thereafter is highly uncertain. This would be like what former BoC Governor Carney did in 2010 when he admitted they didn’t know what would unfold in future, but thought it was important to get off the lower zero bound’s distorting effects after the peak crisis had passed with the argument being that they would slip in a few hikes and then see. This time is the reverse in that a rebalancing of the peak inflation risks may merit starting along the easing path and then seeing what comes.

- Governor Macklem is a dove at heart in my opinion. He reacts too slowly to evidence that inflation is on an upswing but is quick to get out the pom poms at the first whiff of evidence that perhaps inflation has been licked. We saw that when he let inflation get ahead of the BoC. We saw that when he paused prematurely and had to come back and hike twice more. We’ve seen that this year. We’ve seen it in speeches given when he was Senior Deputy Governor under Carney and then when he first became Governor and delivered speeches about pushing the frontiers of maximum employment.

- Canada was growing slack in its economy when GDP was tracking poorly from 2022Q4 through 2023Q4 and this could offer lagging disinflationary pressures through a mildly negative output gap. Maybe that continued into 2024Q1 when GDP grew by 1.7% q/q SAAR, though I’ll come back to that. If the BoC felt such conditions would persist, then it would want to begin easing soon given the lagging effects of rate cuts on growth and inflation. 2024H1 may be rebounding but the BoC’s fudging of its potential output growth assumptions could negate that effect on slack estimates whether correct to do so or not.

- Markets are now pricing about 20bps of a cut and the BoC may not wish to disappoint markets.

The Case for Delaying

What may outweigh these points in my opinion are the following arguments for requiring further patience.

- Do his words matter? They definitely should if he ever wants them to matter again. Macklem wrote and said in carefully prepared testimony on May 1st and again on May 2nd (here) that he wanted ‘months’ of further evidence. The June 5th decision will only be one month since he said that and so he would significantly contradict his own guidance if he cut now which wouldn’t help the central bank restore some credibility around its forward guidance tool after the experiences during the pandemic. If he wanted to tee up June cut pricing, then he either wouldn’t have made such a reference or would have made it sound more imminent. The plural form of his reference to ‘months’ was in the deliberate context of addressing “what most Canadians want to know is when we will lower our policy interest rate. The short answer is we are getting closer. We are seeing what we need to see. We just need to see if for longer to be confident that progress toward price stability will be sustained.”

- Further on the topic of forward guidance is that Macklem always told us that the move toward eventually cutting would be conducted in three stages. First they wanted to see a period of soft core inflation without defining its length; we may be seeing that. Second, they would then have to have the confidence that this will persist; whether they do or not is unclear. Third, only then would they even begin to discuss when to cut rates. As he put it, “When it’s clear that inflation is on a sustained downward track, we can begin discussing lowering our policy interest rate.”

- After being caught off guard by inflation’s ascent over four years from 2020–23 during which its models for inflation completely failed to predict what happened, the BoC should be setting a much higher bar for further evidence and confidence than just a lousy four-month soft patch while having excess faith in the same models that failed. Some of this soft patch’s drivers may be temporary, such as the impact of a warmer and drier than usual winter, and pressure on quasi-regulated prices as argued through several reports like this.

- If the BoC feels it has reason to surprise market pricing, then it has a proven track record of being willing to do so. They surprised consensus with three rate decisions over 2022–23. They’re more focused upon doing what they feel is the right thing to do rather than being pushed.

- By the July meeting, the BoC will be able to evaluate two more rounds of data on inflation, job growth, wages, April GDP, and several other lesser readings. That’s a big data advantage over the June meeting and—if all goes well—would tick Macklem’s requirement for ‘months’ of further evidence. What if you cut now, only to watch everything rip into your forecast update, thereby making it difficult to deliver another cut at least for a long while?

- By the July meeting, the BoC will see the results of its surveys of businesses and consumers including measures of inflation expectations that are on the list of the top things Macklem says he is watching. That too is a big advantage over the June meeting. A fresher small business survey is suggesting that expectations may remain sticky at the top end of the BoC’s 1-3% inflation target range (chart 2).

- July is a full forecast BoC meeting that provides the better opportunity to provide a complete assessment of the outlook if they see merit in beginning to cut at that point. It’s not necessary to have an MPR, but it would be helpful especially for a fundamental turn in policy directions.

- The FOMC communications on June 12th including a revised dot plot may reveal more about where the Committee’s bias rests. The BoC stresses its independence while Macklem also acknowledges limits to this independence. It’s likely that the Committee will reduce its prior median expectation for 75bps of cuts this year to 50bps or perhaps less while sounding relatively hawkish and patient. The BoC may wish to see the outcome.

- Four months isn’t enough evidence that core inflation has dissipated after four years of accelerating inflation. There have been unusual drivers of soft inflation during this patch, and we should want to see more evidence that this isn’t just being driven by temporary factors like a warmer and drier than usual winter that affected discounting in some categories, plus regulatory pressures on several sectors.

- Shelter inflation is still hot and cannot be ignored (chart 3). Governor Macklem has been clear that he is mandated to target 2% all-in inflation, not 2% excluding the quarter of the basket that is shelter ex-mortgage interest. Immigration and severe housing shortages will keep shelter inflation hot.

- The economy is doing better so far in 2024H1 than the BoC had anticipated coming into the start of the year (recap here). That’s especially true ‘under the hood’ given the strongest growth in final domestic demand in two years and the strongest back-to-back quarterly gains in consumer spending of 3%+ q/q SAAR in two years (chart 4). Consumer spending is not shrivelling away, it is thriving and we have to be very careful that rate cuts don’t reignite imbalances that may be waiting in the wings.

- We’re still in the Spring housing market. Amid severe supply shortages, the BoC should be very careful that cutting now would light up the market. The first cut would probably trigger a rally in the relatively cheap 5-year GoC bond that at 3.8%+ is stretching the outer limits of what a neutral rate plus spreads including term premia would suggest to be reasonable. Housing demand is highly rate sensitive; when the 5-year was rallying into December and January, home sales soared by 8.7% m/m in December and 3.7% in January. When the 5-year yield was rising since January, home sales began to soften. A renewed rally could drive a sharp pick-up in demand and price pressures with it in the absence of adequate supply.

- Why a rally in 5s? A tsunami of bond buying awaits the first cut. That view is based upon many meetings with global institutional clients that I’ve had. The common message is that they’re interested in Canada, but often waiting for the first clear signal that it’s a go in terms of easing. When that signal arrives—especially if ahead of most others—then a giant relative rates opportunity unfolds. That’s not necessarily a bad thing in many respects—for traders, for PMs, for markets in general, for borrowers—but it poses the risk that already easier financial conditions in Canada than the US could undershoot much further on the first green light. Canada 5s are relatively cheap at just under 3¾% right now if we take a neutral rate plus term premia and spreads approach, and since markets are prone to exaggerated swings, that Canada five year bond yield could well rally sharply. The BoC had better be confident that this is what it wishes to see.

Why the BoC Should Lag—Not Lead—the Fed

What’s the big rush for the BoC to begin cutting when the Federal Reserve seems to be in absolutely no rush to do so? I think the argument made by others in consensus that Canada faces lower forward-looking inflation risk than the US is incorrect, but, even if it’s true, it is already priced by way of materially easier financial conditions in Canada than the US. The BoC should not encourage a further easing of relative financial conditions because doing so could reignite inflation risk in Canada relative to the US.

How are Canadian financial conditions easier than the US?

- The BoC’s policy rate is already 50bps beneath the Fed’s. Monetary conditions are easier by this measure than in the US.

- Canada’s rates curve is already well below the US across maturities which reflects a lower policy rate and similar pricing of relative central bank moves over the next year. This also indicates easier financial conditions.

- The Fed is dealing with a strong dollar and its mildly disinflationary effects. The BoC is dealing with a weak and serially undervalued currency.

- The terms of trade are providing a lift to Canada’s economy that benefits Canada over the US. Oil prices are a key part of this. Oil prices have risen by more in Canada than the US and they matter more to the Canadian economy than the US economy. Canada Western Select—a proxy for Alberta’s heavy crude output—has risen by about US$15 per barrel so far this year and outperformed WTI’s roughly $5 rise. The WCS discount to WTI has narrowed from a peak of about US$29 per barrel last November to about $13 now with TransMountain playing a significant role (chart 5). This benefits a commodities-producing and exporting country like Canada because it offers trickle down benefits throughout the economy including fiscal balances, corporate financial conditions, and household balance sheets.

Why might inflation risk be higher in Canada than the US going forward?

- Underperformance in Canada’s economy relative to the US may be coming to an end. The US economy may be softening just as Canada’s is getting going. US Q1 GDP growth of 1.3% slightly underperformed Canadian growth of 1.7 especially in terms of details as previously mentioned. US growth may cool more than Canada’s going forward with more favourable supply side developments which I’ll revisit. If so, then output gap drivers of disinflation may be stabilizing or reversing in Canada as they build in the US.

- The economy is now outperforming the BoC’s earlier expectations. Macklem warned Canadians coming into the year that 2024H1 would represent peak pain in the Canadian economy. What has actually happened is that we’re tracking a serial pattern of three consecutive upside surprises to their expectations. 2023Q4 GDP was forecast to post no growth in the January MPR and then the figures posted 1% growth. That’s not great, but they had also forecast 0.5% q/q SAAR growth in 2024Q1 and we just got 1.7% for a pretty sizable beat especially in terms of the core domestic economy (Final Domestic Demand). Early tracking for Q2 GDP growth suggests continued momentum given Statcan guidance that April GDP was 0.3% m/m higher which bakes in about 1½% q/q SAAR growth in Q2 so far but with a lot of data still ahead of us.

- Why such outperformance to BoC expectations? Because they were too aggressive in taking credit for weak growth last year and that clouded their judgement toward a potential rebound this year. The Canadian economy has performed better under the hood than GDP would lead one to believe. 2022Q4 and 2023Q1 were dragged down by inventory shedding that knocked 3–4 percentage points off of GDP in each quarter and that had little to nothing to do with rate hikes that soon. Wildfires and widespread strike activity across the Canadian economy then explained part of the weakness in GDP from 2023Q2 through 2023Q4.

- Apart from relative output gap dynamics, a key relative inflation risk is that population growth in Canada has long been blowing the US out of the water (chart 6). Pre-existing shortfalls of housing supply are being worsened much more so in Canada than the US. The demand-side consequences arrive first and the supply-side consequences are more uncertain and later.

- Canadian wage growth is stronger at about 5% y/y than in the US at about 4% and particularly so relative to much poorer Canadian labour productivity than in the US. The combined effects offer more inflation risk from labour market developments in Canada than in the US. Wednesday’s Q1 productivity figures are likely to further reinforce this point as they could drop by about 1% q/q SA nonannualized and be revised lower for 2023Q4 such that it’s feasible that labour productivity will have fallen for seven consecutive quarters. Canadians are getting paid more in real terms for producing less which is not something the BoC can simply ignore.

- Fiscal policy is still very much in play in Canada while it is shifting to being a net source of drag on US growth (here). In Canada, all levels of government combined are contributing at least ¾% to GDP growth in each of this year and next according to the BoC’s April forecasts that incorporated provincial budgets but not the incremental effect of the Federal Budget.

- In my opinion, the Canadian Federal government’s fiscal plans are a Trojan horse waiting to sneak in behind rate cuts and spring more fiscal easing. If that’s the case, then you would want to be less of a front-loading mindset now that keeps more options open later. The Trudeau/Singh/Freeland government is deeply down in the polls and such governments don’t spend less into election years. The worst possible outcome for reigniting inflation risk would be if the BoC gets sneakily lured into easing and then further vote-buying fiscal stimulus is offered in a Fall statement and Winter budget ahead of the election by no later than next October. I wrote more about this in this daily note.

- Canada’s job market is not cooling. 91k jobs were created in April. 166k have been created so far in 2024. 584k jobs have been created since the end of 2022 and 1 million since the end of 2021. This pace of job growth combined with strong wage gains and poor productivity is incompatible with durably getting inflation down.

- Some will contradict the prior point by stating that this has not kept up with population growth. This is very dependent upon the time period that is chosen. For example, the labour force has risen by 1.1 million since the end of 2021 which is close to the 1 million jobs created. Further, since much of the population growth has been driven by nonpermanent residents, they are not substitutes for other workers in a way that would create wage disinflationary pressures which is really what the argument is getting at. Nonpermanent residents are partly comprised of asylum seekers from Syria and Ukraine and soon the Gaza strip as a humanitarian gesture. They also include temporary foreign workers who send their paycheques back home and take their own pay home with them after spending on the means of subsistence while here. International students have limited spending means and very limited ability to substitute for other workers.

- Canada is capably handling mortgage resets. At some point, rate cuts will be needed back in the direction of a neutral stance with the key 5 year GoC bond yield at about 3.67% somewhat cheap now. But delinquencies remain very low, so do consumer bankruptcies, and banks’ provisioning relative to the sheer size of their mortgage portfolios have merely mean-reverted toward something more normal (chart 7).

ECB—DETERMINED TO RUSH A CUT

The European Central Bank is widely expected to cut its deposit rate by 25bps to 3.75% on Thursday. 96% of consensus expects it and markets are almost fully priced for it. Officials have either not leaned against this expectation or have teed it up with their comments while in some cases taken it as a given and skipping ahead to discussing when the next cut may be delivered.

And that’s what is likely to be more important. Guidance on the path forward is likely to be expressed as data dependent. There is a lot of runway between now and the next decision on July 18th, although most officials are sounding as if they are setting a high bar to go back-to-back. Markets have nothing extra priced for July and about half of another 25bps hike priced for September and so there is scope for the near-term forward rate path to be impacted by President Lagarde’s guidance.

We should not take what the ECB does as necessarily the correct course of action based upon its past misdeeds over several crisis points in its relatively young history. At a minimum, if so intent upon starting to ease, it should be extremely careful going forward. The case for such care is compelling.

For one thing, core inflation in m/m terms has been persistently hotter than is seasonally normal in every single month so far this year. The month of May saw the third hottest gain compared to like months of May on record (chart 8). Other months this year have performed similarly above what is seasonally normal. This is not like Bank of Canada where at least one can say core inflation has been in a soft patch notwithstanding the broad narrative provided in that section of this note; the ECB cannot point to this recent soft patch and doesn’t have the credibility required to communicate high confidence that inflation has been licked on a go-forward basis.

What the ECB can point to, however, is that measures of inflation expectations have come down, through not fully toward target (chart 9).

Furthermore, negotiated wage gains have been running at a hot pace including so far this year which suggests difficulty in getting inflation durably on target. Indeed data on wage increases for new job postings has been cooling but remains above the 2% inflation target, and does not speak to the ongoing repricing of collective bargaining agreements that are very important in Europe (chart 10).

The ECB would have to have more faith in its ability to forecast inflation going forward now than its track record throughout the pandemic would support.

My principle all along has been that you should be patient so that when you get to delivering cuts you can do it in a consistent, determined, and sustainable way. The cost of additional damage until greater certainty has been achieved would be rewarded by more decisive action later. The FOMC, to its credit, and perhaps the BoE, RBA, RBNZ and some others are among the few global central banks that are willing to signal patience even if that means going against markets or prior guidance. That isn’t something that I sense is happening at the ECB.

RBI—STILL ON HOLD

Consensus unanimously expects the Reserve Bank of India to hold its repurchase rate unchanged at 6.5% on Friday.

Core inflation has been falling from 5.2% y/y in June of last year to 3¼% now, but headline CPI remains above 4% and currency stability concerns may have the RBI retaining a cautious bias until clearer evidence arrives that the Federal Reserve is moving toward easing.

RUSSIAN CENTRAL BANK—WOULD A HIKE FIGHT INFLATION’S PAST DRIVERS?

A tail in consensus thinks that hikes might return on Friday. Seven out of nine in consensus expect the key rate to be held at 16%, but a couple expect 100–150bps of hikes. It’s certainly conceivable they would have to resume tightening, given that core inflation has been back on an upswing to over 8% y/y. What could keep the central bank on hold may be a sense that the upswing in inflation reflects lagging effects of past depreciation of the ruble over 2022 into mid-2023 whereas the currency has been relatively stable this year. They might decide to allow the effects to continue to work through and remain in monitoring mode.

CANADIAN JOBS—SUMMERTIME’S STANDING ARMY

Canada updates job growth, wages and related labour force measures such as hours worked, population growth and the size of the labour force for the month of May on Friday at the same time as US payrolls.

I’ve estimated a rise of 30k with a slight up-tick in the unemployment rate to 6.2%. Wage growth may accelerate again after a mild soft patch in April (+0.1% m/m SA) along a volatile trend.

What this estimate is mainly banking on is the continued filling of vacancies by very rapid population growth. That could be a particularly powerful effect into the summer job market. As Jay Parmar’s chart of the week illustrates on the front cover of this publication, the massive surge of temporary/nonpermanent residents in the 15–24 category is a standing army of folks willing to work in seasonal roles across sectors like accommodation and food services.

US NONFARM—A WHIFF OF CANADA?

US payrolls might have a hint of Canada to them as well. Canadians have been used to soaring population growth for quite a while now, but it’s a more recent phenomenon in the US. More rapid population growth may be just enough to keep nonfarm payrolls rising at a guesstimated 205k pace on Friday with wage growth expected to hover just shy of 4% y/y.

Unlike Canada, however, the US is paying for its (lower) wage gains through productivity growth (chart 11). The Fed may therefore be less concerned about the wage-price connections net of productivity considerations than the BoC.

Several job market readings may inform nonfarm expectations in advance. ISM-services-employment for May (Wednesday) could be one of them. So could Tuesday’s lagging JOLTS measure of job vacancies for April. ADP payrolls for May (Wednesday) and Challenger job cuts (Thursday) could also play such a role.

MEXICO ELECTION—MUCH IS AT STAKE

Mexico’s presidential election will finally be held this Sunday, after an almost year-long electoral process. Scotiabank’s Eduardo Suárez who is based in Mexico City wrote this primer on the election that offers a good summary of the main candidates’ platforms, what is at stake, and why this election could prove to be the most important in Mexico’s recent history.

OPEC+ MEETING—JUST A PLACEHOLDER?

Some believe that the decision to conduct Sunday’s OPEC+ meeting online instead of in-person means that the scope for surprises is low. Oil analysts generally believe that the meeting will result in extending production cuts of 2.2 million bpd with a fuller assessment of global supply and demand conditions toward month-end. Any surprises could be impactful into the Monday market open across energy and related markets such as the bond market’s assessment of inflation risk.

Voluntary OPEC+ production cuts are reducing global oil inventories in the first half of 2024 and contributing to significant spare crude oil production capacity (chart 12), but growth in world oil production this year is partly offset by growth from outside of OPEC+ led by growth in the US, Canada, Brazil and Guyana. The EIA expects the startup of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion on May 1st to alleviate existing distribution bottlenecks and allow for gradual increases in crude oil production.

GLOBAL MACRO ROUND-UP

The week’s main expected events have already been covered but here are a few other relatively more minor considerations.

Canada—Tumbling Productivity

The Bank of Canada on Wednesday and Friday’s jobs report should be more than enough to whet one’s whistle insofar as interest in Canada goes. Other developments should be fairly light. Q1 labour productivity (Monday) probably resumed its downward descent after a mild gain in Q4 that interrupted five consecutive quarterly declines in output per hour worked. Purchasing managers’ indices for May (Wednesday) will simply get lost in the BoC’s dust. Trade figures for April and the Ivey PMI for May, both on Thursday, should offer low market risk.

US—Thin Gruel Beyond Nonfarm

Friday’s nonfarm payrolls will dominate the week’s macro risks. ISM-manufacturing for May (Monday) might get a quick glance amid expectations it will remain marginally in contraction territory. Vehicle sales in May (Monday) may have hit the 16 million SAAR mark again, based on industry guidance. Construction spending during April (Monday), an expected rise in total factory orders in April given the already known durables number (Tuesday), a wider trade deficit during April given we already know the merchandise component (Thursday), and regular weekly releases like jobless claims will complete the line-up.

Inflation Updates—Asia-Pacific and Latam in Focus

A round of Latin American and Asia-Pacific inflation reports for May will begin arriving on Monday and unfold throughout the week. South Korea and Indonesia (Monday), Thailand and the Philippines (Tuesday), Taiwan (Thursday) and then the LatAm troika of Mexico, Chile and Colombia (Friday) are all scheduled.

Other LatAm Readings

Latin American markets will also consider Chile’s monthly economic activity index for April (Monday) that will track GDP growth, possibly an update on Mexican wages during the week, and several Brazilian reports including Q1 GDP, industrial output, purchasing managers indices and trade figures throughout the week.

Other Asia-Pacific Reports

Australia’s economy is expected to eek out modest growth when Q1 GDP is updated on Tuesday. The economy has grown for 10 consecutive quarters if so.

Japan updates real wages for April (Tuesday) that are expected to continue to fall. The past two year’s of Shunto wage gains affecting less than one-in-five Japanese workers have yet to begin showing up in average wages. That’s a key criteria for the Bank of Japan’s confidence that 2% inflation can be durably achieved.

Europe Faces Little Beyond the ECB

Thursday’s ECB communications will dominate market attention this week since other calendar-based forms of macro risk will be light.

A mild exception may be that Germany’s economy is expected to post somewhat better readings for factory orders (Thursday) and industrial output (Friday) while Friday’s exports might face downside risk off a prior strong gain.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.