The bilateral relationship between Australia and China is set to remain somewhat challenging, posing a risk to Australia’s economic outlook.

This report discusses two medium-term scenarios for the bilateral relationship and their corresponding impact on the Australian dollar.

Diplomatic tensions between China and Australia remain elevated, posing a continued risk to the Australian economic outlook given the country’s reliance on Chinese demand for its exports. The bilateral relationship has been strained for some years already, yet it tensed up significantly in April 2020 following Australia’s call for an international inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 outbreak. Since then, China has imposed various restrictions and/or tariffs on imports of Australian barley, wine, red meat, coal, lobster, cotton, and timber, and it has warned Chinese citizens against travelling to Australia. Meanwhile, Australia’s authorities have advised that Australians may be at risk of arbitrary detention in China. In addition, the Australian government’s decision to suspend its extradition treaty with Hong Kong after China imposed the National Security Law on the territory has challenged the relationship further. Please refer to the Appendix for a more detailed timeline of the conflict.

We note that Australia’s economic dependence on China is much larger than China’s reliance on Australia. China is Australia’s most important export market; it purchases 42% of Australia’s total global shipments and half of its commodity exports (See chart 1 for Australia’s exports to China). Moreover, the Australian services sector has found significant support from Chinese demand in recent years; as of 2018, over 15% of Australia's total tourist arrivals come from China—one of the highest shares among advanced economies globally—while China is also a notable source of international students in Australia. China’s economic dependence on Australia is mainly limited to commodities; in 2019, Australia was the supplier for 60% of China’s iron ore imports (chart 2) and 43% of coal imports (chart 3).

Given the uneven importance of the bilateral economic ties, this report looks at two scenarios for the Sino-Australian economic relationship and how each would impact the trajectory of the Australian dollar. We first discuss a scenario in which the relationship between Australia and China stabilizes on the back of a modest de-escalation in the US-China tensions. The second will discuss the potential for a further deterioration in the bilateral relationship, putting Australia’s iron ore shipments to China at risk.

SCENARIO 1: STABILIZATION IN RELATIONS

Protectionist biases globally are expected to ease slightly over the next couple of years, reflecting the new US administration’s policy agenda. We expect President Joe Biden to increase the US’s multilateral engagement with the rest of the world and to restore more traditional forms of diplomacy in its engagement with China. While we note that there seems to be bipartisan support in the US Congress for being tough on China, we do not expect the US-China relationship to worsen under the Biden Administration. As such, any de-escalation—or even just a stabilization—in the US-China conflict would allow the US’s allies, such as Australia, to continue deepening their engagement with China in areas of mutual benefit.

In the context of a less-inflammatory policy environment globally, we believe that Australia and China would be able to avoid a further escalation in their bilateral conflict. In fact, we assess that there is some potential for improved diplomatic dialogue between the two countries following the expected ratification of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (the world’s largest free trade agreement in which both Australia and China are signatories) in 2021. Moreover, once the COVID-19 pandemic fades, a more stable relationship would likely allow for a resumption of international travel between the two countries.

Under this scenario—combined with our base case forecast (table 1) of maintained growth-supportive monetary and fiscal policies globally (including in Australia and China) through 2022—we expect China’s economic growth to remain strong, keeping the country’s commodity demand solid. Such a backdrop would underpin global commodity prices, benefiting Australia’s export sector. Prices of iron ore—Australia’s main export—are expected to stay elevated this year, averaging at 115 USD/t in 2021, before easing somewhat to 85 USD/t next year as supply in Brazil picks up and speculative activity lessens. Accordingly, Australia’s terms of trade (chart 4) are anticipated to remain favourable through 2022.

The AUD Under Scenario 1

We assume steady bilateral relations between Canberra and Beijing in our base case outlook for the AUD. We expect the AUDUSD to reach $0.80 later this year (table 1, again), in keeping with a generally weaker USD tone, firm commodity prices as the global economy and global trade recover, and strengthening domestic growth which will reduce pressure on the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to ease monetary policy further in the coming months—and increase the odds of a conclusion to its A$200 bn bond buying programme by the end of 2021.

The AUD staged one of the strongest rebounds among the major currencies from the COVID-19-inspired market volatility and is currently trading more than 25% above the level prevailing at the end of March last year. It did, however, also experience one of the sharpest declines of the major currencies as the pandemic spread in early 2020, falling some 17% from the start of January through to March. We have noted in other publications that AUD extreme weakness to the 0.60 cent point or below has always been associated with significant market turbulence and heightened volatility (around the dot com crash, Great Financial Crisis, and last March's volatility, for example). The AUD typically recovers in a strong and sustained manner from these episodes of extreme weakness and this supports the case for steady gains in the AUD in the months ahead. Equity market volatility as implied by the CBOE’s volatility index is still about twice as high on average as in 2019 and recently reached a three-month high. A decline from these levels should lift the AUD.

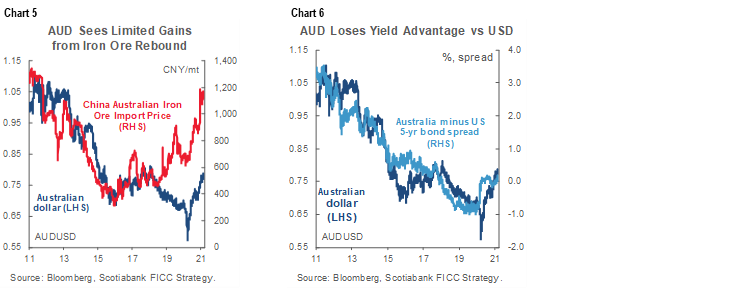

From a longer run point of view, the currency has only recovered a little more than a third of the sell-off that took place against the USD from the $1.10 peak seen in 2011 to last year's trough at $0.55 and remains below both its 10-year and 20-year moving averages which are clustering around the $0.80 point. The Aussie traced the near 80% drop in iron ore prices between 2011 and 2015 but has, all things considered, failed to capitalize on the rebound in iron ore to roughly 10% below its decade-ago highs (chart 5), with the narrowing of the AUD’s yield advantage over the USD to blame for the currency’s underperformance (chart 6).

While the slide in iron ore prices stopped in 2015, Australia’s 5-yr spread over the US continued its drop since late-2010 to near minus 1% in 2019. The 5-yr spread returned to around par last year as the Fed cut rates by 150 bps compared to the RBA’s 65 bps reduction but has still about 400 bps (or 80%) to make up in ground lost since its peak in late-2010. The RBA’s Kent noted recently that were it not for the bank’s policy actions (rate cuts, yield curve targeting, and bond purchases), the AUD would be about 5% higher from current levels—around $0.82. We think that the bank will close out its A$200 bn bond-purchase programme by year-end, while maintaining its yield-curve control policy, and keep rates unchanged through our forecast horizon. Combined with a tapering of the Fed’s bond purchases by early-2022, the AUD is unlikely to gather much support from rate differentials but an improved growth outlook (at home and abroad) with robust commodity prices and easing virus risks will act as modest tailwind.

Considering that speculative positioning currently is relatively flat, it is not hard to envisage some potential for the AUD to overshoot our forecast and reach the $0.83 levels on the back of strong export prices and lukewarm (or no further deterioration in) relations with China, which would equate to the 50% retracement of its long-term decline from $1.10.

SCENARIO 2: FURTHER ESCALATION OF THE CONFLICT

The opposite trajectory for the Sino-Australian relationship would be a further deterioration, potentially triggered by miscalculated political judgements by either party. We assess that from the Australian viewpoint, the biggest risk related to the conflict is that China’s retaliatory actions spread to iron ore. As over 80% of Australia’s iron ore shipments are destined to China, a significant drop in exports—similar to that in coal (chart 7)—would be a substantial blow to the economy. In June 2020, China implemented some changes to customs inspection rules for iron ore. While the new rules are meant to streamline customs processes, we note that they could potentially be used for retaliation, i.e. to slow customs clearance for Australian iron ore. Nevertheless, given China’s dependence on Australian iron ore to feed its steel industry, we assess that an imminent escalation covering iron ore is unlikely.

A worsened conflict would naturally hurt Australia’s external sector. Moreover, it would have a negative impact on consumer and business confidence, slowing Australia’s nascent economic recovery following the pandemic-triggered recession. Accordingly, the labour market, consumer spending and business investment could take longer to rebound, requiring Australian monetary and fiscal policymakers to maintain accommodative policies in place longer than we currently expect. Indeed, should confidence be hit hard, the government and the RBA would likely step in to provide further stimulus to the economy. We assess that additional monetary easing would most likely be in the form of expanded quantitative easing, yet we point out that the potential for a benchmark interest rate cut from the current level of 0.10% into negative territory could not be fully dismissed.

The AUD Under Scenario 2

In the event of a further deterioration in bilateral relations, we expect that markets would move quickly to price in slower domestic growth and the risk of further monetary stimulus from the RBA into the AUD. While it remains an option, we do not think the RBA will be clearly motivated to test the negative-rate waters, particularly as Chinese trade measures are an external factor; a rate cut may only have a marginal economic impact and could risk increased froth in domestic housing markets.

An escalation of the China-Australia conflict could significantly delay a rate liftoff—to possibly lag the Federal Reserve’s first—and keep the RBA’s quantitative easing and yield-curve control programmes in place (or expanded). Until a resolution is found at the executive level, Australia’s economic potential will remain subdued. With low rates for longer on the horizon and other central banks moving closer toward normalization, the spread of Australian debt yields over the US and Canada could again turn significantly negative and lead to an underperformance of the Aussie.

While Australian commodity producers may face barriers in trade with China, global demand for raw materials would not necessarily diminish as the post-pandemic recovery becomes more widespread; commodity prices might not fall significantly and Australian producers could—eventually—find alternative markets for products (at lower prices, however, while unable to recoup losses in ‘slower’ trade with China), tempering downside pressure on the AUD. Nevertheless, an escalation in Chinese tensions with Australia could motivate the G7 (or most of the G20) to show a united front against Chinese geopolitical pressure that would result in heightened uncertainty in financial markets and slow global growth (as in 2018-19) amid Sino-Western discord. In this scenario, commodity prices would face an additional obstacle that would drag on the AUD and other commodity currencies.

The combination of lower rate differentials, subdued domestic confidence, geopolitical tensions, and weaker commodity prices could pull the AUD exchange rate to as low as the key $0.70 mark in our estimation—compared to our latest forecast of $0.80 by end-2021. China’s push to become the leading global economy means, however, that the Xi government will have to eventually abstain from long-lasting measures that impact its imports of raw materials. We think that the AUD would eventually recover somewhat thanks to an improvement in bilateral relations—at least with diminished impact on goods trade—but sentiment in the currency will remain cautious unless Australia significantly diversifies its export destinations (a tall task).

CONCLUSIONS

We expect the Sino-Australian relationship to remain challenging over the coming quarters—and years—despite the fact that both countries benefit from the bilateral economic ties. In the foreseeable future, Australia will likely deepen its efforts to diversify its export markets and reduce its trade dependence on Chinese demand, yet we assess that any progress is set to remain limited. Given China’s expected real GDP growth outperformance over the coming years, the country will continue to increase its economic might globally. By our calculations, China is on track to become the world’s largest economy within the next decade or so. Accordingly, Australia will continue to be exposed to fluctuations in Chinese demand for years to come.

We highlight that there is significant uncertainty regarding the outlook for the bilateral relationship. Out of the two scenarios laid out in this report we assess that the first scenario is slightly more likely. Nonetheless, any material improvement in the relationship is unlikely to happen within the next few quarters as handling the adverse economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic takes priority and as the political/policy environment remains strained globally. Realistically, we assess that a stabilization of the relationship would represent the most optimal outcome in the current context. We consider that the second and more pessimistic scenario is unlikely to materialize in the near future given the importance of iron ore to China, particularly now that the Chinese economy is recovering from the COVID-19 slump with the help of stimulus-driven fixed investment. While iron ore may be safe from retaliatory actions, we note that some other Australian exports—particularly agricultural goods such as wheat, dairy, and fruit—could be at risk instead. Nonetheless, the economic significance of such exports is small enough that the Australian economy as a whole would be able to avoid significant harm.

Our baseline Australian dollar scenario incorporates some degree of lingering anxiety over future China-Australia relations but global forces in commodity prices and an improving risk mood should lift the AUD toward the $0.80 mark by end-2021. The AUD may see some additional gains as the RBA possibly concludes its A$200 bn bond purchase programme later this year, but Governor Lowe and other central bank officers will likely ‘talk’ the currency down. In the negative scenario, the AUD is at risk of touching the $0.70 level as heightened trade tensions force the RBA to maintain ultra-accommodative policy for longer while other central banks (namely the Fed) proceed with policy tightening, further eroding the AUD’s yield appeal. A combined Western response to China’s trade actions would also lead to a period of elevated market anxiety and depressed growth that weaken commodity- and risk-sensitive currencies like the AUD.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.

Foreign Exchange Strategy

This publication has been prepared by The Bank of Nova Scotia (Scotiabank) for informational and marketing purposes only. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable, but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness and neither the information nor the forecast shall be taken as a representation for which Scotiabank, its affiliates or any of their employees incur any responsibility. Neither Scotiabank nor its affiliates accept any liability whatsoever for any loss arising from any use of this information. This publication is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any of the currencies referred to herein, nor shall this publication be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The general transaction, financial, educational and market information contained herein is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. You should note that the manner in which you implement any of the strategies set out in this publication may expose you to significant risk and you should carefully consider your ability to bear such risks through consultation with your own independent financial, legal, accounting, tax and other professional advisors. Scotiabank, its affiliates and/or their respective officers, directors or employees may from time to time take positions in the currencies mentioned herein as principal or agent, and may have received remuneration as financial advisor and/or underwriter for certain of the corporations mentioned herein. Directors, officers or employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations referred to herein. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. This publication and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced in whole or in part, or referred to in any manner whatsoever nor may the information, opinions and conclusions contained in it be referred to without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable. Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia and Scotiabank Europe plc are authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. The Bank of Nova Scotia is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available on request. Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.