- There is a sweet spot when it comes to economic immigration—where everyone is better off over time—but it is narrow and Canada has strayed far off course.

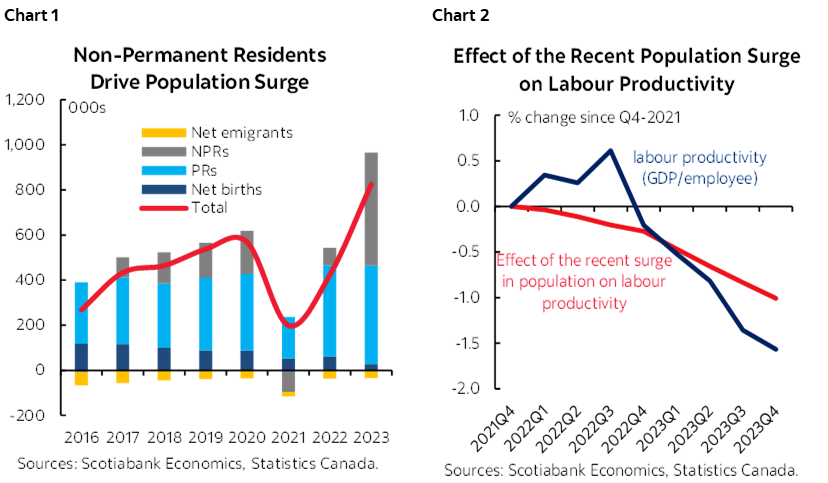

- Canada welcomed 1.25 mn new residents last year with a final count that was over 2.5 times the policy-deliberated permanent resident target as temporary arrivals surged (chart 1).

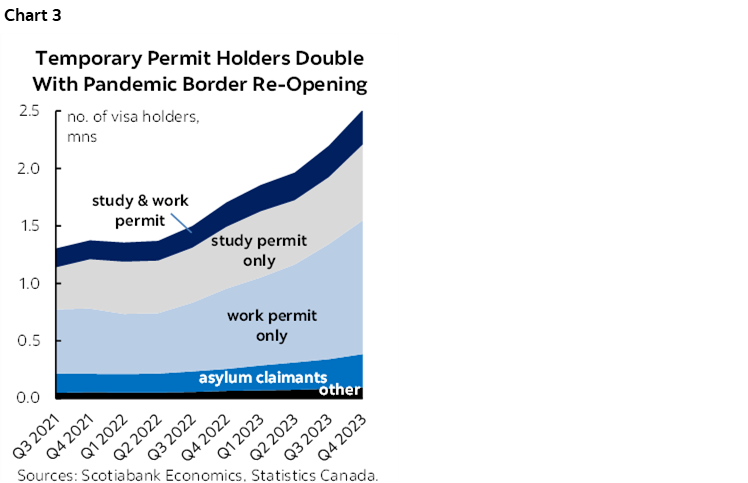

- Given the chronic challenge of low investment rates in Canada, we estimate Canada’s productivity-neutral pace of population growth is only around 350 k annually—temporary or otherwise. In the absence of stronger investment, increases in population beyond that lower the capital to labour ratio and depress productivity. We estimate about two-thirds of productivity declines since 2021 stem from this population shock (chart 2).

- Near-term lifts to headline growth (and government revenues) are delaying needed adjustments even as real-world constraints mount. Policymakers are left scrambling to plug holes and place caps across a highly fragmented system.

- Canada’s immigration policy needs a reset, not quick-fixes. A start would be firmly placing economic immigration1 in the context of a broader productivity agenda. That agenda should focus on boosting capital spending to match the historic investments already made on the immigration front (i.e., in human capital).

- A sharper focus on economic potential could make better use of Canada’s predictive points-based admissions tools for permanent residents, while exploring an equivalent bar for businesses hoping to hire labour from abroad. Collaborative investments in newcomers’ potential well-after landing are also critical.

- Canada needs a number for planning and predictability purposes, but that should be a ceiling for total net inflows irrespective of status. Permanent (economic) admissions should be driven by potential (i.e., not a set number) with a premium on procedural transparency to re-anchor expectations.

- At the end of the day, population growth should be a source of economic strength and should give Canada a competitive advantage over countries with declining populations. That can only happen if Canada ensures that immigration policy is focused on individuals with high economic potential, and is matched with equally significant increases in business investment.

- Absent that, the country will remain on the current trajectory of declining productivity and competitiveness. This is a path Canada can ill afford.

NO POINTS FOR PREDICTABILITY

Canada’s population growth has been explosive. The country officially added 1.25 mn people in 2023 for a 3.2% y/y uptick according to Statistics Canada. The dramatic surge has taken policymakers (and forecasters) by surprise. A near-exclusive focus on permanent residents (PRs) blinded policymakers to the exponential growth in non-permanent residents (NPRs). While the feds not surprisingly hit their PR target (465 k), a net 800 k (1.3 mn gross) non-permanent residents settled in Canada last year (chart 1).

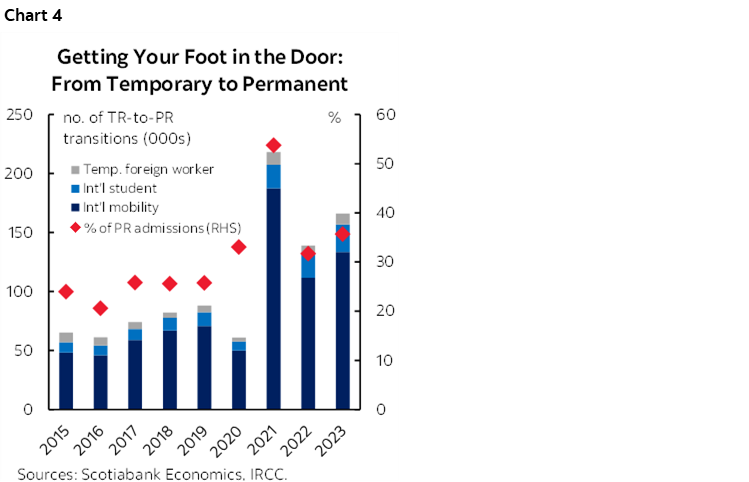

Temporary permit holders in the country have doubled since borders re-opened. Over 6% of Canada’s population is currently non-permanent (and closer to 8% including government estimates of undocumented residents). While lapses in international student programs have received much air time, study permits ‘only’ increased by about 25% annually over the past two years (chart 3). Work visas shot up by almost 70% last year (to 900 k) and are driving the headline numbers (and January numbers are up 30% y/y).

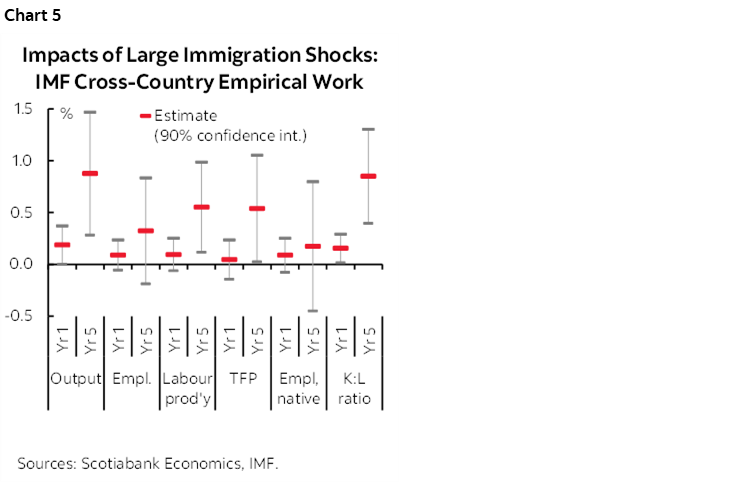

Temporary is the new permanent. Part by design, part by default, an increasing number of permanent admissions are already in the country. Half a million temporary visa holders transitioned to permanent status since 2021—comprising over 1/3 of admissions in 2023 (chart 4). Admittedly it is a bit of a mug’s game to get a snapshot given the wide range of pathways to entry across both permanent and non-permanent categories, flows between them, variable visa terms, and on-going policy changes. But broad trends are pretty stark.

Policy drivers will dominate where the headline number goes in the years ahead, but a best-guess is a slowing, but still growing, population. The PR target of 485 k is likely firm this year. The new student visa cap (at 360 k new issuances) would likely stall growth but stabilize the stock of international students in the country. The wild card is work permits. Absent a pullback in the pace of new work visa issuance (and assuming 1/3rd annual attrition), net population gains would still be closer to 1 mn in 2024. If anything, the pace of population growth has accelerated so far this year based on data from the Labour Force Survey: the rise in population in January and February is the fastest two-month pace in history.

Meanwhile, immigration has unfairly become a lightning rod for almost all that ails Canada. From productivity woes and housing shortfalls to hospital wait-times and over-crowded classrooms, there is collective finger-pointing at the lack of preparedness for the massive influx of people into the country. Weak line of sight on the numbers, along with unchecked pockets of abuse (or at least liberal use) in Canada’s immigration system, have not helped.

Canada confronts some tough policy choices ahead. Deliberations should be grounded in sound economic and social principals and informed by best-available data (which is ample).

NO FREE LUNCH

Popular rhetoric is increasingly unanchored in economic principles. Population growth, in isolation, is neither a driver nor a drag on output per capita over the long run. According to classical economic theory, output per capita is a function of the equilibrium unemployment rate (NAIRU), the equilibrium participation rate, the capital to labour ratio, and a residual magic sauce (total factor productivity). Therefore, investment (tangible and intangible capital) and total factor productivity play a determinant role in the standard of living.2

Empirical (real-life) economics suggest there is a sweet spot. Population growth can drive sustained improvements over time, but the context and conditions are quite narrow: shocks are one-off, they are relatively modest, and capital investment is “vigorously” responsive, according to recent IMF cross-country work (chart 5). Its earlier analysis also underscores a potentially reinforcing role for active labour market and integration policies that can be conducive to positive and sustained economic gains for all from immigration.

Canada has surpassed that sweet spot by multiples. Since the beginning of 2022, Canada’s working-age population has been growing at an average annualised pace of about 2.5% versus its pre-pandemic trend of just over 1% per year. (The mean shock of the IMF’s ‘large-wave’ study was just under 1%.) Perhaps most importantly, Canada’s investment response has been anything but vigorous. This should come as no surprise given the extensively documented and long-standing disappointing investment outcomes in Canada.

The magnitude of the population shock has further muted this investment response. The surge in immigration almost certainly contained what would have otherwise been even more substantial wage increases and, in so doing, has made labour a cheaper option than capital. This naturally incentivized firms to forego investment in lieu of larger workforces. Given that, it was more or less a certainty that the surge in population would lead to a decline in productivity. This is what we find in the context of our macroeconometric model of the Canadian economy. Given the typical response of investment in Canada to macroeconomic factors, we estimate that the rise in population contributed to 1.0% of the massive 1.6% decline in GDP per employee relative to end 2021 (chart 2, front). We further estimate that a productivity-neutral rate of population growth over this time would have been around 350 k annually. That is a fraction of what actually occurred. Moreover, we very roughly assess that business investment would need to rise by about 15% over a two-year period for each million increase in population beyond the average historical pace of population growth. We have seen such large increases in capital formation in the past, but those episodes were few and far between and they have tended to occur when oil prices have risen sharply.

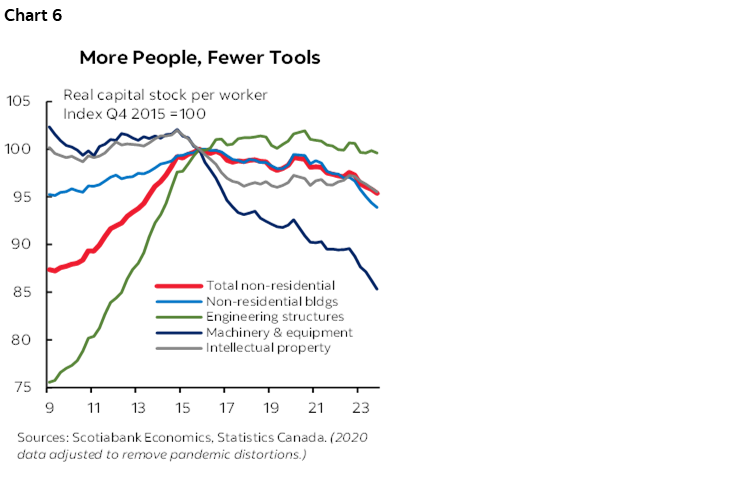

Canada’s long-standing productivity challenges don’t bode well for a textbook snapback. While there are still plenty of pandemic and policy distortions in near-term wage and productivity data across sectors, the aggregate picture sends a clear signal as output per worker plunges. Canada appears firmly in territory of ‘capital dilution’ where high and persistent population shocks—exacerbated in the context of a weakened investment response—are permanently driving down the capital-to-worker ratio (chart 6). Immigration is not the root cause, but an accelerated uptick is not helping on the margin.

FAILING THE MARSHMALLOW TEST

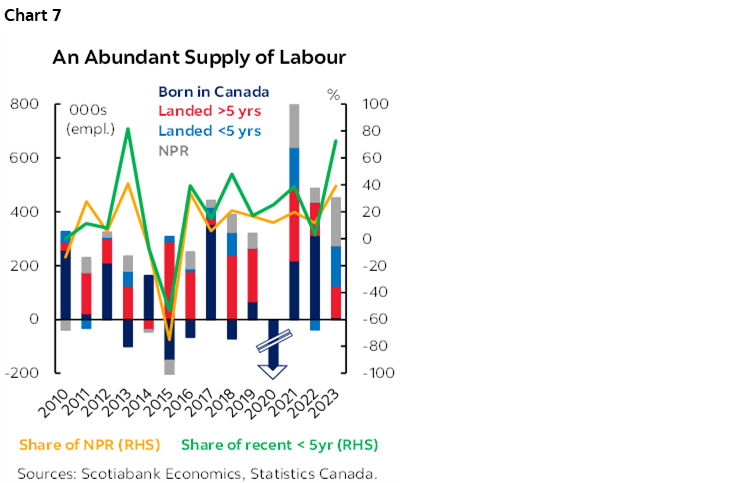

Near-term economic gains are delaying needed adjustments. Labour markets have remarkably absorbed the population shock so far. More than half of the 1.7 mn jobs added since 2021 have been filled by immigrants (landed and temporary) versus their economy-wide share of about one-third. Growth has accelerated, in particular, among recent arrivals with temporary workers accounting for almost 40% of job gains last year—and over 70% including those that arrived within five years (chart 7). The unemployment rate has been ticking back up slowly as growth in the working population outpaces still-in-the-black job reports.

This is driving aggregate output. Keeping in mind GDP is a function of hours worked, we estimate that this incremental labour supply (i.e., increases beyond the pre-pandemic trend) underpinned a 1.4 ppt gain in the GDP level since 2021. It has also padded government coffers with triple-digit billions in revenue windfalls as personal income (and consumption) tax receipts continue to come in above expectation.

While the simple average per capita productivity decline is sharp, it is far from broad based (yet). Pocket book sentiment is no doubt weak, but Canadian households across the income spectrum are still better off today relative to pre-pandemic across a range of income and balance sheet metrics. It is mostly the incremental worker—the subset of newcomers filling low wage positions—that is getting the immediate short end of the stick, whether through skills-job mismatches, wage gaps, or sticker shock on finding a place to live—owned or rented.

The bite will be broad based over time. Rebuilding capital stock commensurate with population growth would require more investment, implying higher savings—at the expense of near-term consumption. Canada is not on that path.

IT’S NOT (JUST) THE SIZE THAT MATTERS

It would be misguided to focus exclusively on the number. Though overly simplistic and with a host of caveats, maintaining constant living standards roughly implies that the average income of newcomers converges with that of the broader population over time. Compositional choices would dictate effort levels across categories.

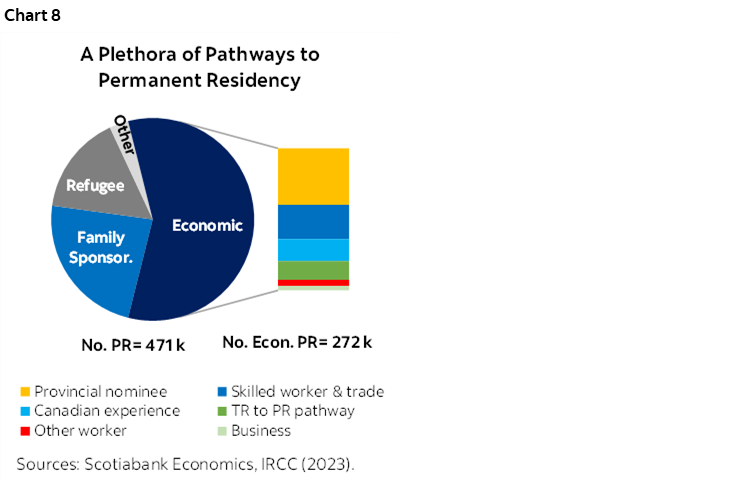

Currently, about 30% of permanent resident admissions are first-order economic. While the fed’s “economic” stream comprised 58% of PR admissions in 2023, the count also included spouses and dependents (as it should) at roughly a 1-to-1 ratio (crisscrossing imperfectly aligned CRA and IRCC data). Meanwhile, family sponsorship and humanitarian streams accounted for 23% and 16% of admissions, respectively (chart 8).

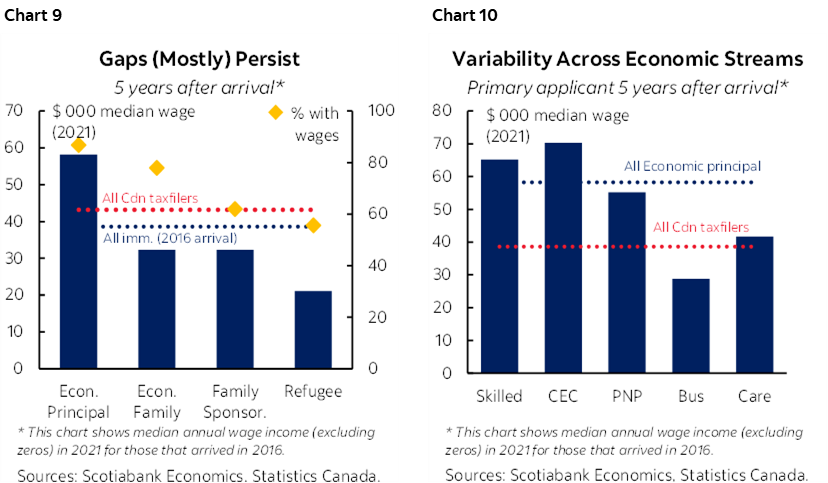

Only economic principal applicants surpass the median Canadian income threshold. And they do so by a decent margin, earning a third more than the average Canadian five years after arrival (chart 9). Family-related categories (spouses and sponsorships), on the other hand, earn about 25% less five years later. Trailing partners in economic streams, however, are far more likely to participate in the labour force than those under sponsorship streams. There is also variability within economic streams with some surprises: underwhelming results in the entrepreneurial stream and decent outcomes for caregivers (chart 10).

POINTS FOR PREDICTABILITY

Policymakers should have a good line of sight on these economic outcomes. Canada’s points-based system (i.e., its Comprehensive Ranking System), coupled with exceptional longitudinal data, does a pretty good job of predicting future earnings potential. There is room to sharpen this tool (as noted by C.D. Howe and IRCC itself), but arguably the biggest gains could come from using it more broadly. Last year, only 71 k invitations were extended through this centralized points-based system or 15% of the 465 k PR target.

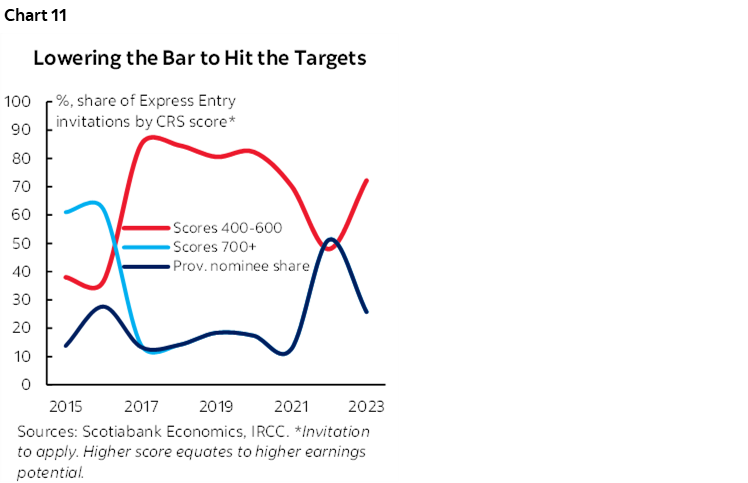

Hard targets are exposing trade-offs around potential. Higher PR targets have driven cut-off scores lower, especially once the growing number of provincial nominees are netted out of high scores (chart 11). In concession to provinces, these candidates are awarded 600 points from the get-go even if earnings down the road does not fully corroborate this points-premium relative to Canadian experience or skilled categories (chart 10, again).

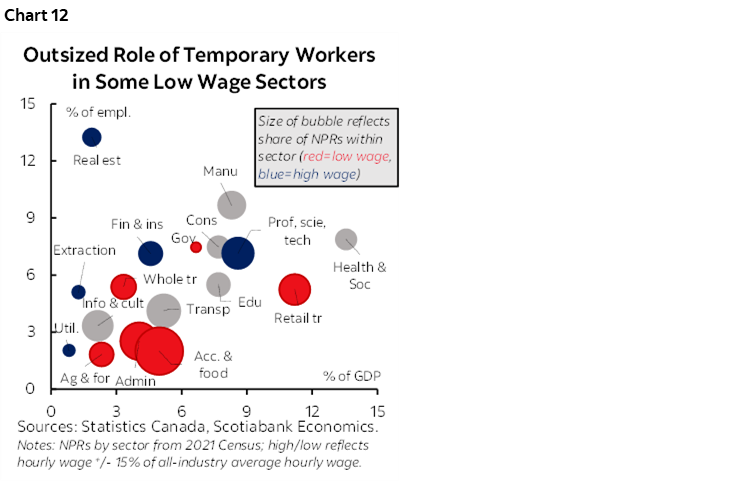

Canadian education and experience clearly enhance economic outcomes, but the two-step model has become a double-edged sword. A recent PBO report points to pre-pandemic progress in narrowing wage gaps of newcomers, owing in part to pre-landing Canadian experience. But Statistics Canada had presciently warned back in 2020 that uncapped temporary programs would run the risk of capture by short-term labour market needs. While non-permanent residents are filling labour gaps across all sectors including highly productive ones, they are overweight in lower wage ones (chart 12). According to census data, almost 30% of NPRs worked in retail and food & accommodation, for example. (That share is likely higher today.)

Unfettered temporary programs have also left the federal government with a massive wall of mismanaged expectations. The vast majority of those in the country temporarily (3 mn temporary or undocumented) aspire to stay in the country. The stark reality is that many won’t successfully make that transition. There were 16 k judicial reviews filed in federal court in 2023—averaging over 40 a day—contesting IRCC decisions. The federal government now not only has to critically manage the growth of new residents, also the large stock already here. And as it contemplates policy options around undocumented residents, moral hazard is a material risk to be balanced against the government’s role in mismanaged expectations.

Canada has also not done a particularly good job of investing in newcomers’ potential after landing. Apart from gains attributed to the two-step process, there has been minimal progress on narrowing education-skills mismatches. The overqualification rate (i.e., university degree holders working in jobs that require no more than a high school education) among foreign-educated immigrants is twice as high as Canadian-born or Canadian-education peers. Only around 10% of settlement services were tapped for employment-related support pre-pandemic. Both suggest a bigger role for active labour market policies.

RAISING THE BAR

Canada has an opportunity to reset the narrative on immigration but it faces some tough policy choices. Immigration alone does not drive productivity gains, but better policy conditions could at least directionally support stronger welfare gains over time. This would require some substantive changes.

- The first is a better articulation of its economic goals. The current implicit objective of economic immigration is to improve the living standards of all Canadians, but current weakly-targeted economic pathways don’t put Canada on that trajectory. An explicit articulation of the goal could help with execution, evaluation, and accountability, while better-informing the links between Canada’s economic and demographic ecosystems.

- Canada should sharpen its focus on the economic potential of newcomers in its admissions processes. Improvements, and importantly base-broadening, of the Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) could increase transparency, remove subjectivity, and strengthen economic outcomes (for newcomers and for all Canadians) over time.

- Canada should favour an admissions threshold based on this potential, not on a fixed quantity of permanent residents. Policy choices could calibrate the composition and time frames over which gaps are to narrow, but the math would then largely determine the ‘break-even’ or the points-based threshold required to maintain living standards over time. Greater transparency could also go a long way in better managing expectations of temporary arrivals hoping to translate education and experience into permanency.

- Canada still needs a planning ceiling on the top-line number of annual arrivals irrespective of channels. With the number of permanent residents determined by potential, additional non-permanent entries should bring the total net inflow up to that ceiling. This would enable appropriate planning around infrastructure—public and private—and would also send a clear signal to stakeholders on the limits to ‘cheap labour’ or ‘quick cash’ business models.

- Canada should raise the bar for businesses looking to tap labour from abroad. It could consider developing a business-equivalent to the CRS: a data-driven, predictive tool that leverages both sectoral and corporate-specific performance metrics to identify the most productive use of incremental labour supply. Such a system would reward sectors and businesses that have a track-record of investing in both human and capital potential. It should also reduce the government’s footprint in picking ‘strategic’ sectors (though a carve-out for healthcare-related categories within well-governed frameworks is likely essential).

- Canada could do more to help maximise the potential of newcomers well-after they have arrived. Active labour market policies, including partnerships with academic and business sectors, could close wage gaps and labour shortages more efficiently, while preserving important labour mobility. We earlier proposed a shared accountability mechanism (a “workplace passport”) to ensure a continued focus on actively closing post-arrival gaps faster.

This type of focused agenda could get Canada back to its ‘sweet spot’ and even raise it over time in the context of a broader productivity agenda. This is in the interest of all Canadians including those recently or yet-to arrive in the country.

1 This note recognises that immigration also serves other non-economic priorities including humanitarian need, but it focuses only on economic-related categories while acknowledging economic trade-offs to compositional policy choices.

2 For a more comprehensive discussion, see work by the Canadian Labour Economics Forum.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.