MORE AMBITION NEEDED TO NARROW THE EDUCATION-JOB MISMATCH

- Labour shortages in Canada are likely to persist as demographic forces unfold.

- Addressing shortfalls will require an all-hands-on-deck approach including enhancing the participation of women, older Canadians, newcomers, and other marginalised populations in the workforce.

- But a comprehensive approach should focus not only on increasing headcounts, but also maximising the potential of those already in the labour force.

- Newcomers are increasingly coming to Canada highly educated and motivated to contribute, but more often than not occupy positions that do not leverage their learning. Whereas two-thirds of newly arrived immigrants hold university degrees, only about 40% work in jobs requiring them versus 60% of Canadian-born peers.

- Reasons behind this education-occupation mismatch are complex and diverse including both supply and demand factors, but persistent labour constraints against anaemic economic growth potential should put impetus on aggressively tackling such impediments.

- For illustrative purposes, a 5-year commitment to newcomers that aims to narrow an individual’s education-occupation gap within 5 years of arrival—extended to those that arrived within the last 5 years and those likely to arrive within the next 5—could drive “job upgrades” for about a quarter-million newcomers over this period (chart 1).

- While the numbers may not radically shift Canada’s growth trajectory absent complementary growth policies, they would at least directionally support higher productivity gains. (And to be clear, demand-side policies would also be needed to adequately absorb such upgrading of supply.)

- Importantly, narrowing the mismatch would have a substantial impact on newcomers and their families where the wage penalty can be in the order of $20–25 k annually.

- Governments, along with stakeholders, should set higher ambitions in providing the supports and opportunities to enable newcomers to reach their full potential over time.

- The journey should not end when newcomers arrive in Canada and enter the labour force, rather this should just be the beginning.

JOBS, JOBS EVERYWHERE

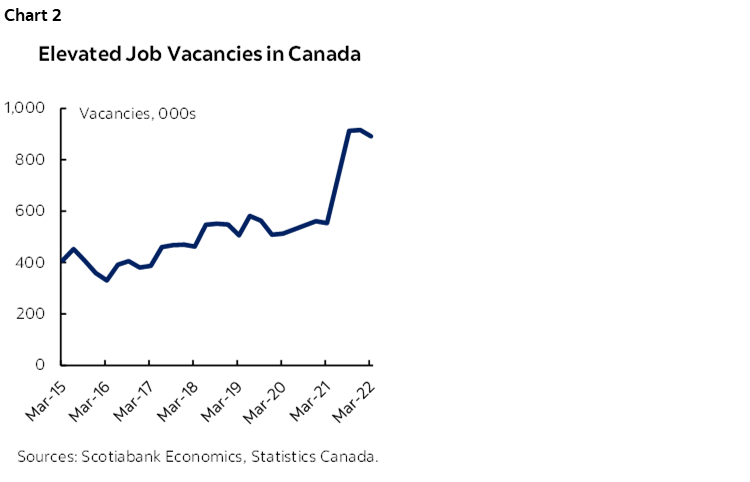

Labour shortages across Canada are persistent and pervasive. More than 400 k new jobs have been added to the labour force since the onset of the pandemic, participation rates are largely back to pre-pandemic levels, and the unemployment rate sits at an historic low. More than 1 mn jobs remain vacant—a doubling relative to pre-pandemic levels—across sectors and regions (chart 2). Over 40% of businesses are reporting labour shortages, according to the Bank of Canada.

As policymakers engineer an economic slowdown, this will remove some of the tension in incredibly taut labour markets, but structural shortages will endure. Recall, even prior to the pandemic, over a third of businesses were signalling labour shortages. There are currently three workers supporting each retiree—effectively a doubling of the old-age dependency ratio in the last half-century. Meanwhile, one-in-five working age Canadians is approaching retirement age, according to 2021 census data, and Canada’s natural-born population is set to turn negative by the end of this decade.

Addressing these shortages will require an all-hands-on-deck approach. Early on in the pandemic, Scotiabank Economics set out the case for closing female labour force participation gaps that sees roughly half-a-million working age females sitting on the sidelines relative to male peers. We have recently highlighted the economic case for incentivising older Canadians to retain labour force attachments longer that could conservatively add another 1.4 mn to the labour force. We have also detailed the economic dividends that boosted immigration levels are paying in Canada’s most populous provinces as newcomer arrivals hit a new high-water mark last year at just over 400 k and rising.

The role of immigration features prominently in hand-wringing around labour shortages. A recent survey by the Business Council of Canada found that two-thirds of businesses rely on international recruitment to fill gaps. Unlike boosting workforce participation of those already in Canada that provides a one-off boost in terms of output growth, immigrants provide a steady influx of highly educated and motivated entrants into the labour force. In the last decade—looking through pandemic disruptions—immigrant workers accounted for almost 85% of Canada’s labour force growth (chart 3). The reliance on newcomers is broad-based across sectors (chart 4), but particularly acute in some sectors such as healthcare where one-in-four registered nurses and one-in-three nurses aids are immigrants, according to Statistics Canada.

BEYOND THE HEADCOUNT

In the pursuit of adding more workers, Canada must not lose sight of enhancing the potential of those already in the labour force. Simplistically, national wealth is a function of people: the hours they work and their productivity in those hours. Growth can be enhanced by adding more people to the labour force and/or by increasing their productivity through investments in tools, technologies, or training. Canada’s track record on labour productivity is lacklustre and there are few quick-wins to unlocking stronger gains. Setting a stronger trajectory would require, for example, massive shifts in capital deployment, a revamping of educational systems, or a more strategic approach to sectoral development.

Recently-arrived Canadians are—or should be—low-hanging fruit. They are, for the most part, coming to the country at prime working age—or even at the start of their careers as international students—and are highly-educated. About two-thirds of newly-arrived working-age immigrants (i.e., those having arrived within the last five years, ages 24–54 years) hold university degrees versus about a third of Canadian-born peers. Currently, over 40% of university-educated working-age Canadians are immigrants, punching well-above their 30% share in the labour force for that age cohort.

However, newcomers are far less-likely to occupy positions that leverage their training. Admittedly dated now, 2016 census data suggest less than 40% of immigrants occupy a position that requires their university credentials versus 60% of the Canadian-born population. This education-job matching ratio has been relatively stable for Canadians, but has deteriorated for immigrants in recent decades (chart 5). Forthcoming census data should show some improvement given the enhanced role international students are playing in the pathway to permanent residency, but it is unlikely to meaningfully change the picture.

The drivers behind under the education-occupation mismatch can be diverse and wide-ranging. On the supply side, they can include credentials recognition for regulated sectors, the quality of the education received abroad, the transferability of skills in a new setting, a lack of relevant Canadian working experience, and/or language or cultural barriers. Market forces may discount, in part or entirely, the value of the foreign-earned credential even if gaps exist in the Canadian labour market. Supply-side theorists often refer to the mismatch as an “underutilisation” of education.

There are also likely important demand drivers behind the mismatch. The Canadian economy may not be generating enough demand for the increased supply of foreign-born and Canadian-born university graduates, both of which have been rising over recent decades (chart 6). The Parliamentary Budget Officer signalled this structural mismatch back in 2015, while Statistics Canada also attributes some of the gap to over-supply relative to demand. Concurrently, the demand for lower-skilled positions has been under pressure, particularly acute in some sectors including front-line and back-office functions, but also in other service-related sectors as consumption as a share of the Canadian economy continues to grow. Newcomers are increasingly filling these lower wage jobs—many opting to do so even if they hold higher degrees—as Canadian-born workers vacate them (chart 7). Demand-side theorists often refer to the mismatch as an “overeducation” phenomenon.

Regardless of the drivers behind the mismatch, the impact on newcomer households can be significant. A host of imperfect data sources point to substantial wage penalties for those working in positions below their credentials. Newly-arrived university-educated immigrants earned on average $21 k less annually than Canadian-born peers whose income averaged $69 k in 2017—a wage penalty of over 40% (publicly-available data is dated but the gap over time has been stubbornly stable). The wage gap narrows for immigrants who arrived earlier (5–10 years ago), but tapers only modestly to $15 k annually (chart 8). This tells an incomplete picture since figures would include the roughly 40% of immigrants in positions commensurate with their education. The wage premium for all Canadians with a university degree versus those with only a high school education averaged close to $30 k annually (though it varies considerably with age/experience), according to 2016 census data (chart 9).

A reasonable guesstimate would put a wage penalty in the order of $25 k annually for newly-arrived immigrants working in positions that do not leverage their university education. This may narrow—but likely only closer to about $20 k annually— in the 5–10 years following their arrival. This admittedly over-simplifies the complexity of isolating ability from education, the imperfect transferability of international education and experience, and the capacity of Canada’s economy to absorb talent, but it signals the potential size of the impact on the individual earner.

QUICK MATH

Narrowing the education-occupation mismatch of recent immigrants could benefit the Canadian economy. For point of reference, of the 800k+ newcomers (ages 25–54) that arrived in the last five years, just over half-a-million hold university degrees, but statistically only about 200 k likely occupy positions that require it. If present trends continue, these numbers will more than double over the next five years. For illustrative purposes, a 5-year commitment to newcomers that aims to narrow an individual’s education-occupation gap within 5 years of arrival—extended to those that arrived within the last 5 years and those likely to arrive within the next 5—could drive “job upgrades” for about a quarter-million newcomers over this period.

This would provide a small boost to national wealth. Admittedly, the numbers are not gamechangers at the national level: a gradual profile of such “job upgrading” could add an incremental ~$16 bn over five years (ramping up to about $6 bn annually by the fifth year) through income channels in an economy of about $2.5 tn (2021). But directionally, at least, it would push Canada’s per capita output in the right direction as, ultimately, it is this metric that would lift overall living standards in Canada. It should also provoke a more thoughtful deliberation on the desired quality and composition of jobs in the Canadian economy over time. After all it is not simply the supply of an educated workforce that is relevant, but also the underlying industrial structures that can leverage these skills.

It could have a very significant impact on newcomers and their families. The potential to narrow the education pay gap—that could sit in the order of $20–25 k annually as noted earlier—could have a meaningful impact at the household level. A recent survey by Scotiabank found that newcomers place higher priority to several key financial goals relative to Canadian-born peers from saving for a first home or car to saving for a family or their education. A host of academic literature also flags the potential psychological impacts of working in a position below one’s education level including lower job satisfaction, job security, quality of life, and health status. These factors may not be reflected in income data, but would have real impacts on newcomers and their families.

DOUBLING DOWN ON EFFORTS TO NARROW MISMATCHES

Narrowing the education-job mismatch for newcomers may not radically shift the economic landscape for the country, but it could make an enormous difference in the lives of newcomers and their families. It could also provoke a more thoughtful conversation about the types of jobs—and sectors—that would benefit Canada’s longer term growth agenda that would benefit not just newcomers, but all Canadians. And it should put emphasis beyond simple job numbers or labour force headcounts to also focus on enhancing the productive capacity of those already in the labour force. Raising the living standards of all Canadians will require lifting output on a per capita basis, not just on the backs of more people in the labour force. Ensuring gains are equitably shared should also be a priority. Closing these gaps would be an important step in that direction.

To be clear, this should not imply that priority be afforded only to potential newcomers in high-skilled categories. Canadians, after all, are learning that newcomers are making outsized contributions in some lower wage sectors including healthcare or long term care where acute shortages are taking a toll on the overall welfare of many Canadians. Furthermore, rich longitudinal data tracking immigrants’ journeys over several decades shows that children of immigrants equally or even out-earn their peers—by almost 30% for 30-year old children of economic-entry families (chart 10). But they shouldn’t have to wait a generation to close these gaps.

Narrowing education-occupation mismatches will require collaboration across sectors. There are clear roles for all levels of government, the private sector, educational institutions, and social impact sectors in addressing some of the obstacles that may impede new Canadians from finding meaningful and rewarding employment that reflects their education and experience over time, and enabling them to substantially improve their own household welfare. There is already a range of settlement supports for newcomers in place, but very few are leveraged for employment purposes (chart 11).

Rapid changes are unlikely to happen overnight—with friction and legitimate barriers on both the supply and demand side— but raising collective ambitions could accelerate the progress. A “workplace passport” for newcomers, for example, could set out aspirational goals set by newcomers themselves with a 5-year plan—and potential supports—to get there. They may start in a lower-skilled position as an entry point in a new country and context, but have an opportunity to chart a better course over time towards higher-skilled and higher-earning opportunities. Governments could incentivize corporate ownership by prioritizing immigration flows to sectors and employers that are committed to supporting such portable passports within a broader framework that considers a sector’s contribution to growth potential, its track record of investing in capital and labour productivity, and/or its essential role in society.

The journey should not end when newcomers arrive in Canada and enter the labour force, rather this should just be the beginning. Entry positions could be a stepping stone, not necessarily the final destination, as they embark on improving their own welfare while contributing to Canada’s economy and society. Beyond moral arguments, there will increasingly be competition for young, highly-educated, and mobile talent as workforces age globally. They will go where their talent is best-recognized and appropriately rewarded.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.