- As the impact of the pandemic on the economy waned, the Canadian business community turned increasingly more optimistic.

- However, the issue of supply chain disruptions, which were expected to gradually improve over 2022, has worsened instead and many business owners now expect these issues to persist at least for the next 6 months.

- The ongoing Russian war in Ukraine is likely to present the Canadian business owners with a complex set of opportunities and challenges, including a continued deterioration in supply chains.

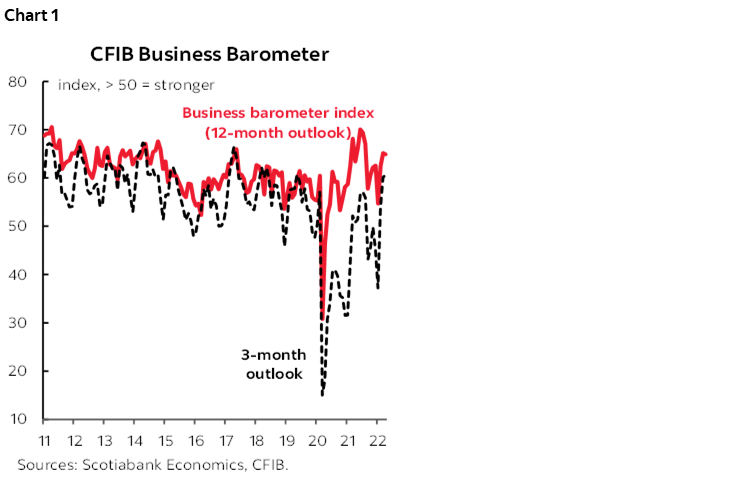

Following almost two years of COVID-19 waves and intermittent lockdowns, the last few months saw a tentative improvement in the epidemiological situation, breathing life into small and medium-size enterprises in Canada. Both the rising vaccination rate, and the less severe Omicron variant that out-competed other strands, led to a more durable rise in economic activity, in particular in the customer-facing industries. As a result, small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) turned increasingly optimistic, despite some recent volatility (chart 1).

WHY HAVE FORTUNES OF SMEs AND LARGE BUSINESSES DIVERGED?

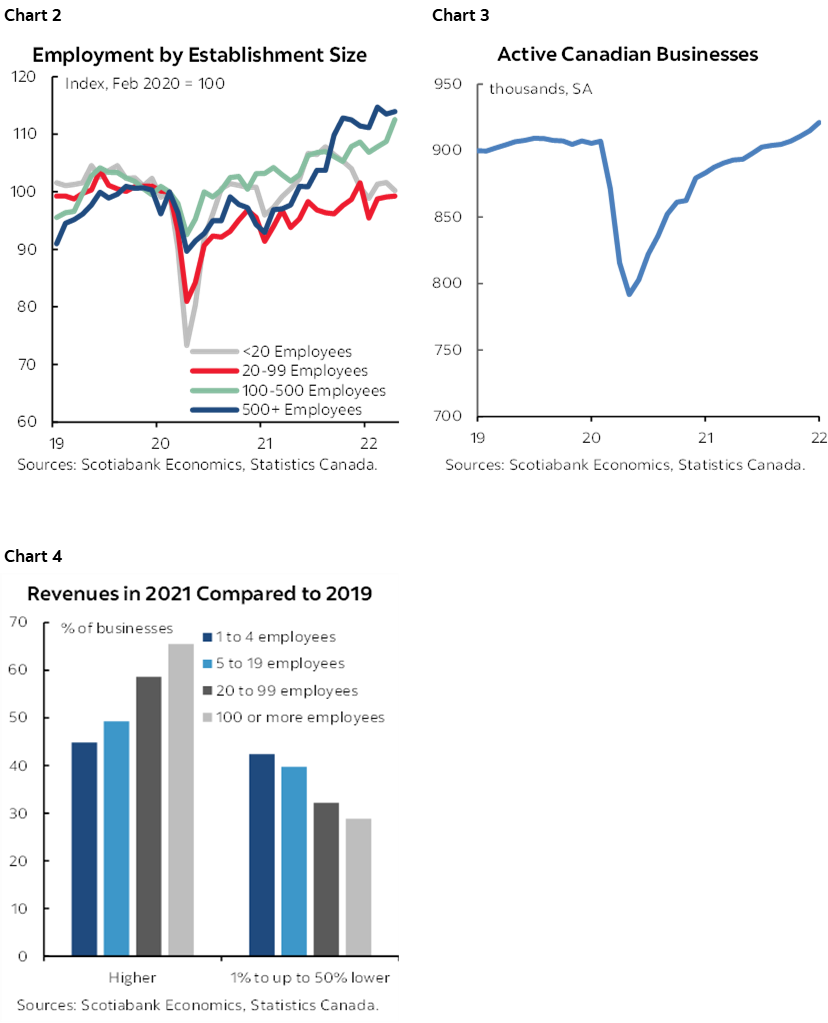

Despite the better macroeconomic context, SMEs somewhat underperformed larger enterprises in the post-pandemic recovery (chart 2). A recent survey from Statistics Canada (link) provides further evidence in support of this. While 66% of large businesses (100+ employees) earned higher revenues in 2021 compared to 2019, this was true of less than 50% of smaller businesses (1–19 employees, chart 4). In addition, 40% of firms in the latter category reported a contraction in revenue of between 1% and 50%, a much larger share compared to those with 100+ employees.

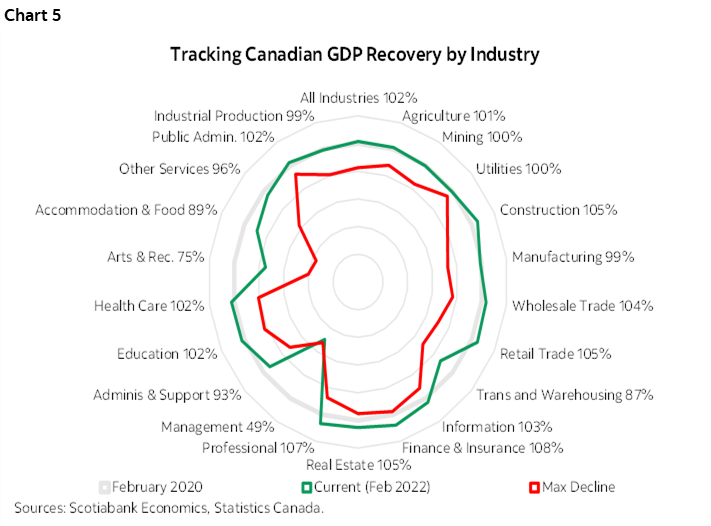

This divergence could be explained by various factors. First, consumer demand in sectors most negatively affected by the pandemic may be taking its time to come back: the level of GDP in these sectors, such as accommodation and food services, is yet to reach the pre-pandemic level (chart 5).

A possible additional factor holding back the recovery at smaller firms could be the increased premium placed on the economies of scale in the post-pandemic economic landscape, as i) sales move online, which reduces the need for a retail sales network and puts larger firms with sophisticated logistics at an advantage, and ii) smaller firms lack bargaining power when competing with larger companies for labour and scarce supplies. The latter is more important in the context of global supply chain disruptions.

On the other hand, as the post-pandemic process of de-globalization gathers pace, large firms that are more likely to rely on complicated global supply chains may find themselves under pressure as supplies become unreliable and costs rise. In this environment smaller firms may benefit from a less complicated production setup and the growing move towards reshoring.

SEARCHING FOR WORKERS, INPUTS

The lack of workers and inputs of production continue to pose a challenge for business owners who have gone through multiple waves of the pandemic, only to see their businesses struggle despite the strong aggregate demand.

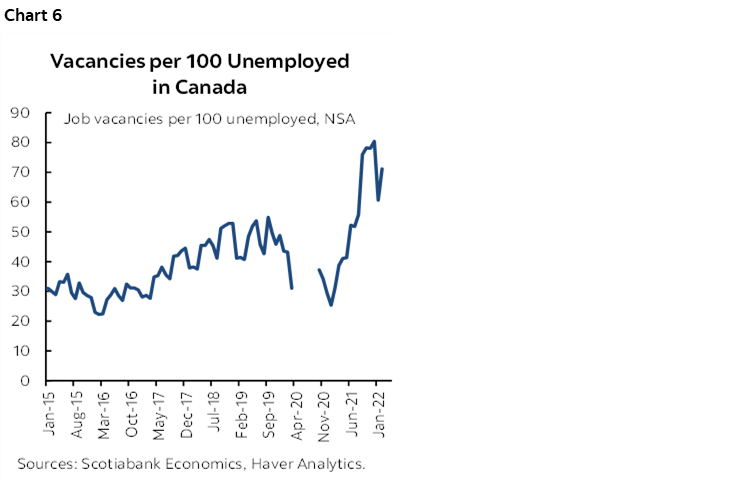

On the labour side, Canada has seen the number of unfilled job vacancies reach historic levels (chart 6) during the recovery. Workers leaving industries where periodic COVID-19 lockdowns made paycheques erratic, the inability of HR departments to hire workers as quickly as they were laid off during the pandemic, and finally exodus from some industries where virus exposure is elevated may explain the high level of unfilled positions in the Canadian economy.

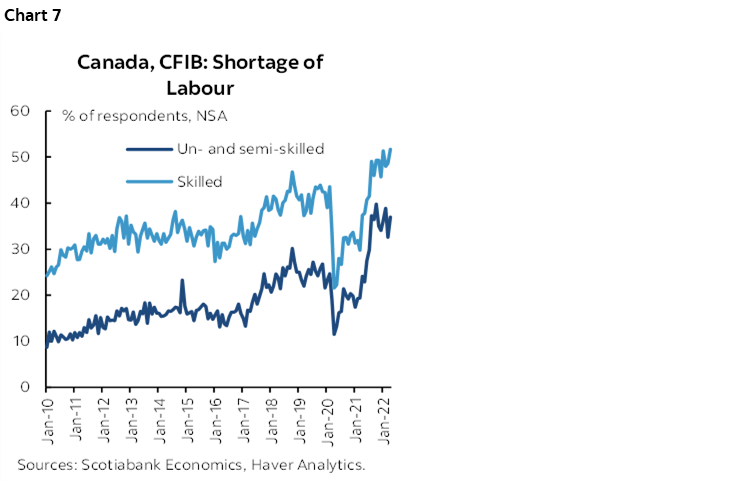

SMEs are not immune to the struggle for talent, as the CFIB survey lays out: a very large share of businesses considers the shortage of labour as an important limiting factor to revenue growth (chart 7). However, one unusual aspect of the labour market recovery in 2020–21 is the high level of demand for lower-skilled workers. This is in contrast to the developments before the pandemic, when the share of high-skilled jobs rose significantly (link) due to technological change encouraging jobs up-skilling.

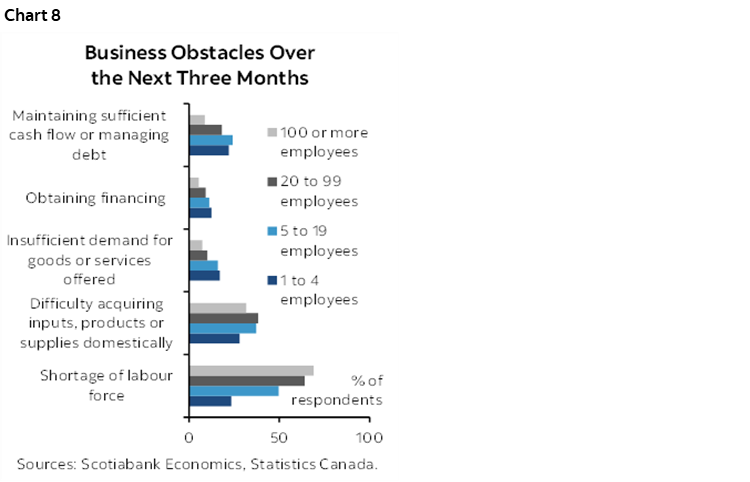

The good news is that there is evidence that smaller firms are somewhat less constrained by the shortage of labour in the short term compared to the larger companies (chart 8), with larger firms overwhelmingly faced with the issue of labour scarcity. Despite this, or perhaps in order to secure an adequate labour force, smaller firms expect to raise wages more on average, compared to larger firms (here). A less optimistic way of looking at these statistics could be that smaller firms do not need additional employees if they find it hard to compete with larger companies for other supplies.

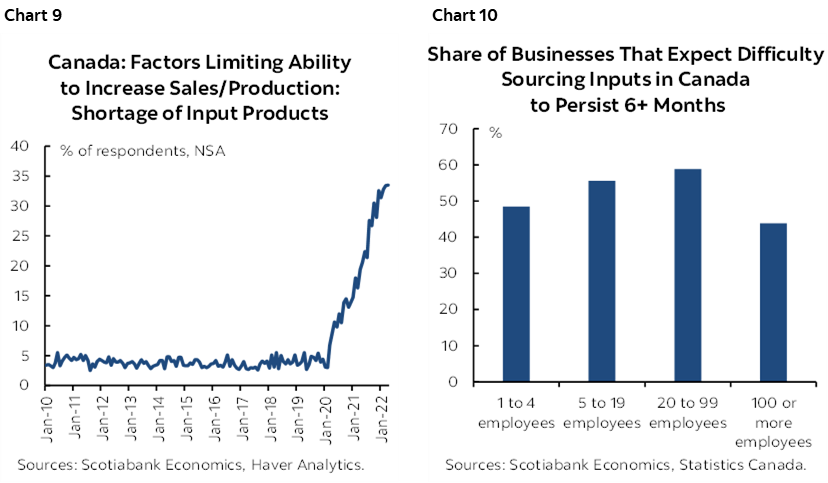

The unreliable supply of inputs is the phenomenon that found its reflection in widespread increases in producer and consumer prices and limited supply of some products. Ever since the start of the pandemic, the share of SMEs who consider might find it difficult to raise production because of a shortage of input products has steadily risen to encompass a third of such firms (chart 9). The question of when the supply chain issues will dissipate is on the minds of business owners, but most forecast that it will take over 6 months for the logistical issues to be sorted out (chart 10).

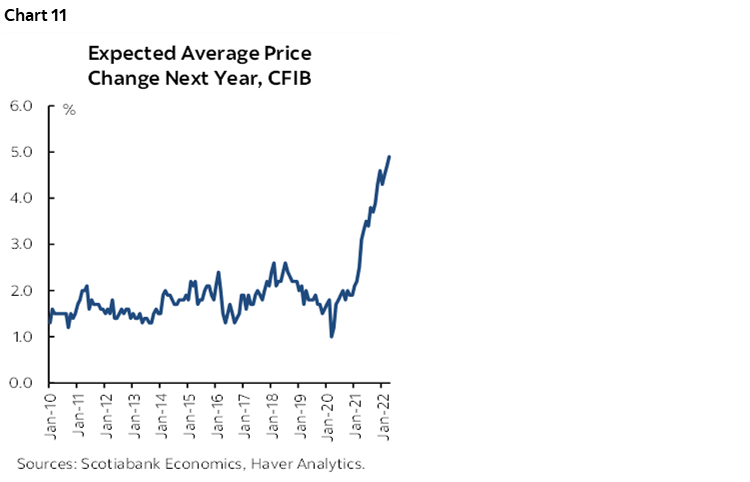

Higher cost of inputs, along with rising wages, all push companies to pass rising costs to customers in the next 12 months. This implies that the strong inflationary impulse, which developed over the course of 2021, still has some legs (chart 11).

MACROECONOMIC OUTLOOK

Where does this leave SMEs in the next few years, with costs going up, and demand in certain sectors still lacking? The good news is that the aggregate demand in 2022 is expected to be strong, and especially for those sectors which are still recovering, as the economy increasingly leaves COVID-19 behind. Scotiabank economics expects growth in overall Canada’s GDP to average 4.2% in 2022 and 3.0% in 2023, with the unemployment rate continuing to move lower through 2022 (here).

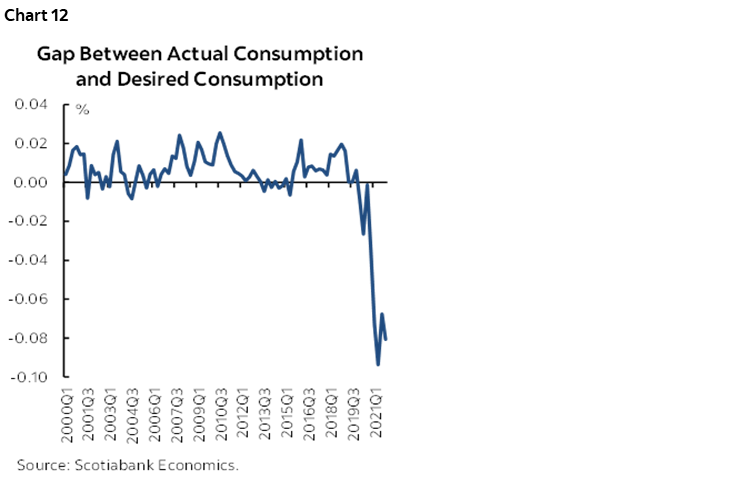

The good news is that strong GDP and employment growth are expected to come disproportionally from sectors that are currently struggling with weak demand due to the residual impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, according to the CFIB Business Barometer, compared to others, firms in the hardest-hit information, arts and recreation sector were much more optimistic about the next 12 months (here). Businesses that service consumers can expect continued strong growth in consumption spending, given the record level of pent-up demand (chart 12).

The overall outlook also assumes that supply disruptions wane gradually over 2022–23, removing some of the upward pressure on inflation over that period. Nevertheless, with overall CPI inflation reaching over 6% on a quarterly basis in 2022, the Bank of Canada is expected to raise the overnight rate sharply in 2022 and 2023, raising the cost of financing for businesses. This could mean that SMEs, who already see a lack of financial resources as one of the factors constraining further business development and the adoption of new technology, should now consider the opportunity to secure required capital in advance of further rate hikes.

LATEST GLOBAL SHOCK—WAR IN UKRAINE

Most of the surveys analyzed in this report were completed before Russia’s war in Ukraine began on February 24th, 2022. The consequences of the war are already profound and far-reaching. It is too early to predict the implications of it on the global economy, including Canada, but some of the broad trends can be tentatively identified.

Most importantly, the risk of a large conflict that takes the world into uncharted territory has risen dramatically, the impact of which on Canada and other countries would be difficult to foresee.

Short of this disastrous scenario, a war confined to the territory of Ukraine with persistent and tough sanctions likely means commodity prices remaining high, which should benefit the commodity-producing Canadian regions. Rising export revenues should also boost broader spending in provinces such as Alberta. On the other hand, higher input costs and worsening supply chain disruptions for certain types of goods (e.g. wheat, fertilizer, metals, etc.), in addition to high gasoline prices, should start to cut into profits of companies. The Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook Survey conducted in the first quarter of 2022 showed that many businesses anticipated even higher input costs and inflation as a result of the war going forward (see here). High gas prices may also sap consumer spending power and undermine consumer confidence.

In the medium to long-term the trend towards de-globalization, both financial and economic, which started during the pandemic, could accelerate due to the increased risk of sanctions, reputational damage and military conflict in countries accused of human rights and international law violations. This may lead to more emphasis on domestic manufacturing and investment, which could benefit domestic firms irrespective of their size.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.