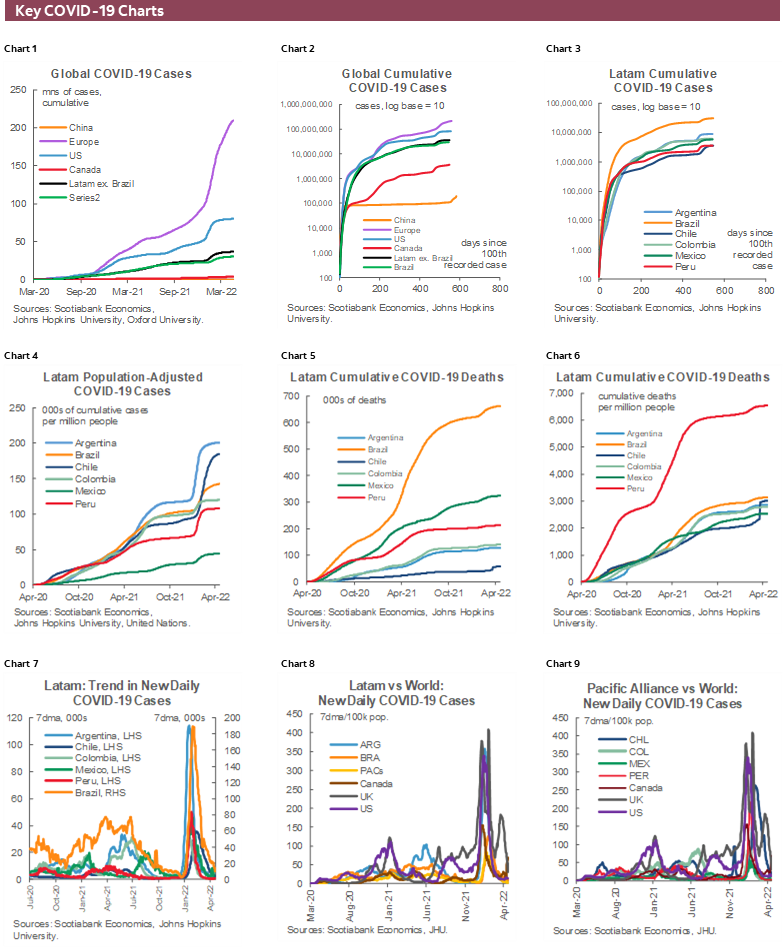

- The IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings highlight the risks to the global economy posed by Russia’s war on Ukraine. Most significant are higher commodity prices and supply-side disruptions layered on pandemic-related shocks to global supply chains.

- Global growth prospects have been revised down and inflation forecasts pushed higher. For the Latam region, weaker external demand and the higher interest rates that will be required to contain inflation represent negative shocks, with expected growth marked down across most of the region.

- Global financial markets have remained orderly, despite large price swings from the pricing-in of geopolitical risks and the economic and financial shocks from the war. But external financing risks remain, which if realized could complicate the financing of large current account deficits. Meanwhile, longer-term challenges loom should the war and the sanctions imposed on Russia lead to a bifurcation of the global economy.

Every April, the world of global finance descends (virtually during the pandemic) on Washington, DC for the “Spring Meetings” of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. The meetings are noteworthy in that they bring finance ministers and central bank governors of the two institutions’ members together to discuss the global economic outlook and key challenges to financial stability. They are also an opportunity for countries to sit down with their public and private creditors and for the various international country groupings (G7, G20, etc.) to discuss common approaches to shared problems. In this regard, the Spring Meetings are part of the governance arrangements for global finance, the lack of which contributed to the demise of the first great age of globalization a century ago.

This year’s gathering is especially notable for two reasons. It is the first time since the outbreak of the pandemic that participants can attend “in-person.” (Though Russia’s finance minister wisely decided to participate virtually in anticipation of a walk-out by other finance ministers.) And, far more important, the meetings are taking place in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the economic and financial consequences that entails.

These consequences are highlighted in the IMF’s flagship publication, the World Economic Outlook (WEO), which revised down the Fund’s forecast for global growth. The IMF now expects the global economy to grow by 3.6% in 2022, down from the 4.4% pace of expansion it projected in January just before the invasion. The reasons for this markdown of economic prospects are not difficult to fathom. Apart from the truly catastrophic 35% contraction of economic activity in Ukraine caused by the widespread devastation of Russian aggression and as the Ukrainian people flee the fighting and mobilize for war, Russia’s economy will be hard hit by comprehensive trade and financial sanctions that the Fund staff expects will shrink output by 8.5% in 2022.

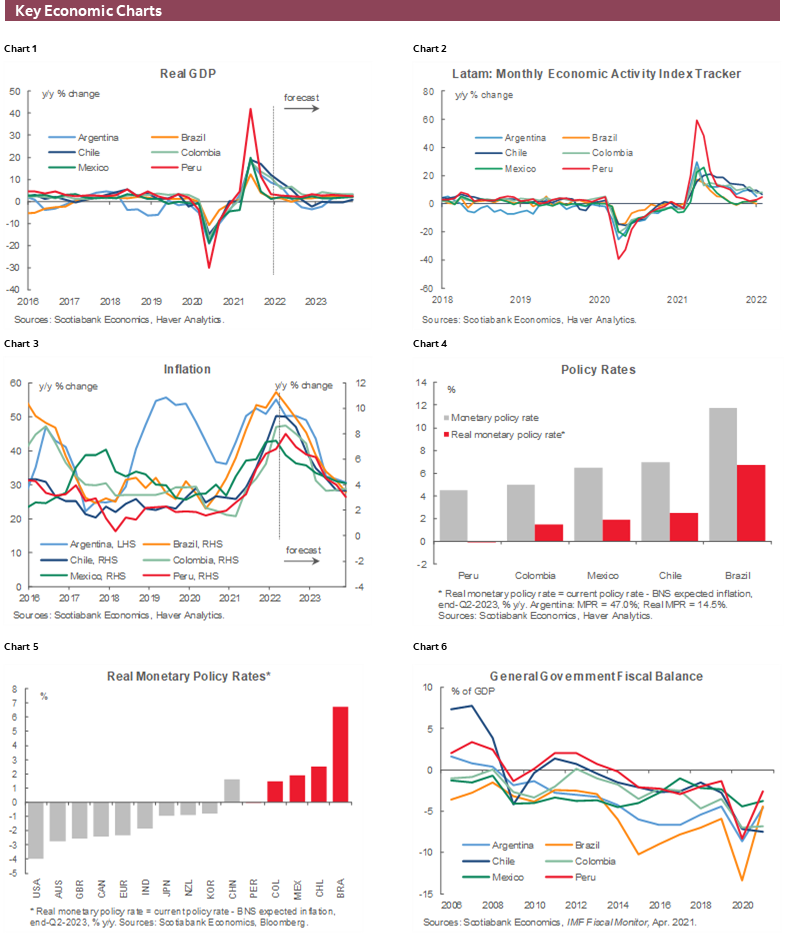

The economic and financial shock waves generated by the war in Ukraine radiate beyond the immediate combatants, as commodity prices spike and global supply chains experience additional disruptions. Higher inflation is the inevitable result. Even before the outbreak of hostilities, central banks in the Latam region and around the globe were grappling with inflationary pressures. The upsurge in inflation from higher commodity prices will, other things equal, likely elicit higher interest rates as central banks strive to keep inflation expectations well anchored. This response seems certain in advanced economies that have just begun to tighten monetary policy. In Canada, for example, March inflation of 6.7% y/y has led Scotiabank’s Derek Holt to call for the Bank of Canada to accelerate its pace of monetary tightening.

A more vigorous monetary policy response by major central banks would suppress activity in interest-sensitive sectors and slow growth. For Latam economies, that would imply less external demand. And with growth rates already coming down from the pandemic-recovery rebound, the unwinding of fiscal stimulus, the effects of inflation-induced erosion in purchasing power on consumer confidence unknown, and heightened uncertainties as geopolitical risks escalate, the possibility of policy error is increased.

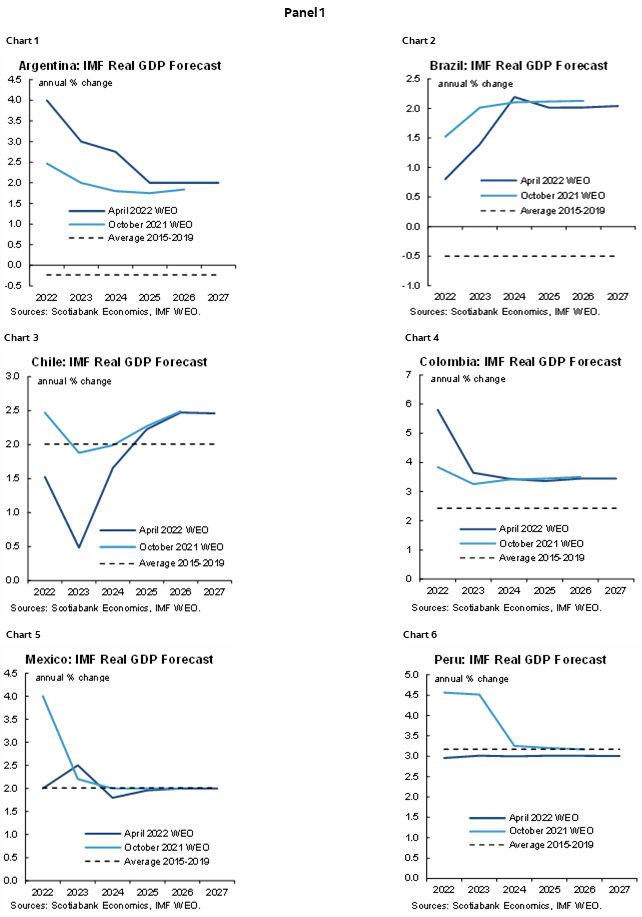

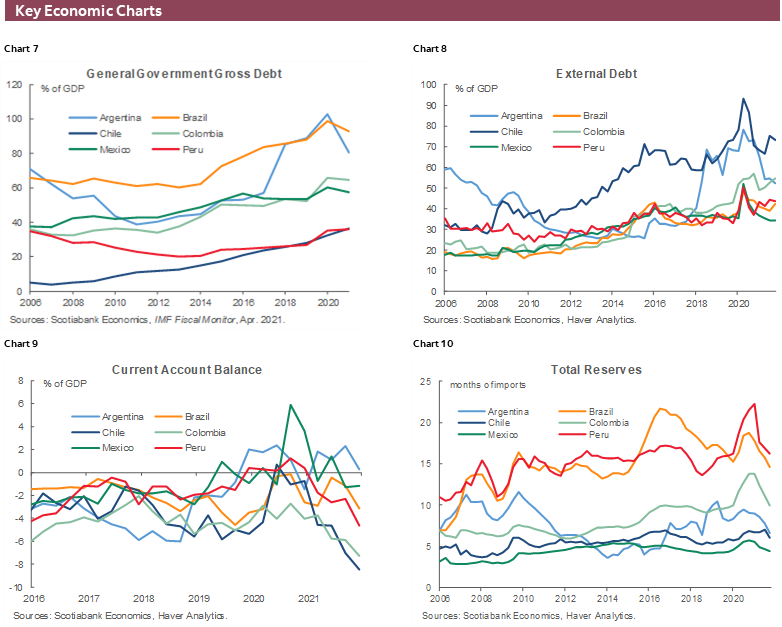

In such circumstances, the risk of recession—or equivalently, output growth below potential output growth—is likewise raised. Panel 1 below illustrates IMF revisions to its forecasts for the Latam region. While near-term growth prospects of Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru have all been revised down relative to the October WEO, the forecasts for Argentina and Colombia have been revised up. Argentina’s forecast probably reflects agreement on an extended Fund facility which, if fully implemented, would facilitate financial stabilization and possibly stimulate investment. However, Colombia’s improved growth outlook can be attributed in part to favourable terms-of-trade effects from higher prices for key commodity exports.

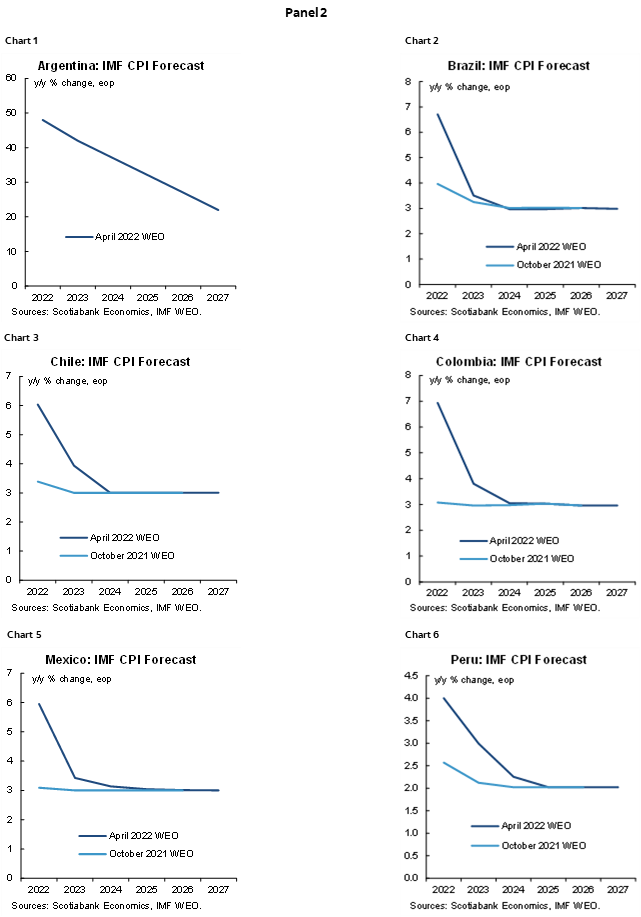

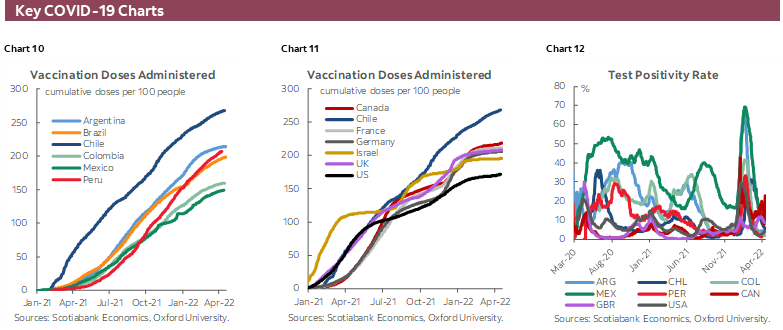

Of course, the Latam region is not immune to higher global commodity prices. As shown in panel 2 (below), the IMF’s consumer price inflation forecasts have been uniformly revised higher, significantly so in most cases. (Prior to the conclusion of the agreement with the authorities, the IMF did not project inflation for Argentina.) Notwithstanding this inflation level shock, the Fund staff—like Scotiabank economists in the region—continue to expect inflation to return to central bank target ranges over time, albeit with the date of re-entry pushed out somewhat.

The projected path for inflation reflects well established, credible inflation-targeting regimes in most Latam countries, implemented by independent central banks. But equally, it reflects the fact that Latam central banks are well ahead of their advanced economy peers in terms of recalibrating monetary policy consistent with inflation-targeting frameworks. In other words, the region’s central banks have backed up talk of inflation control with concrete policy actions.

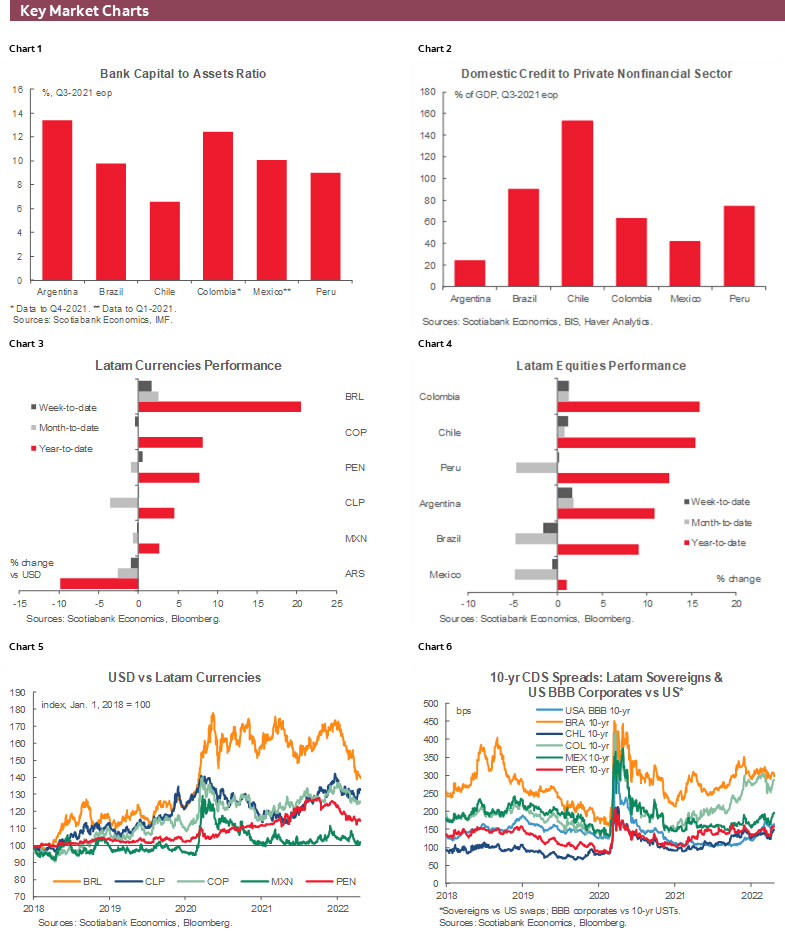

Nevertheless, more aggressive policy responses elsewhere could put pressure on exchange rates, raising the risk of “importing” higher inflation through exchange rate pass-through effects. Such pressures could be exacerbated by shifts in investor risk appetite from heightened geopolitical risks. Of particular concern is the possibility that the outbreak of war, the implementation of draconian sanctions, combined with the threat of secondary sanctions and the use of counter sanctions (including the use of cereals and other food grains as a strategic weapon), could create fissures in the global economy, reversing three decades of globalization, and generate disorderly global financial markets and large-scale capital flows.

Yet, despite such fears, the region’s financial markets have been remarkably buoyant. Moreover, global asset markets that have seen large price movements have been orderly, without the dysfunction that accompanied the global financial crisis more than a decade ago or the onset of the pandemic in March 2020. This is one piece of good news from the Spring Meetings amid the horrific humanitarian disaster unfolding in Ukraine.

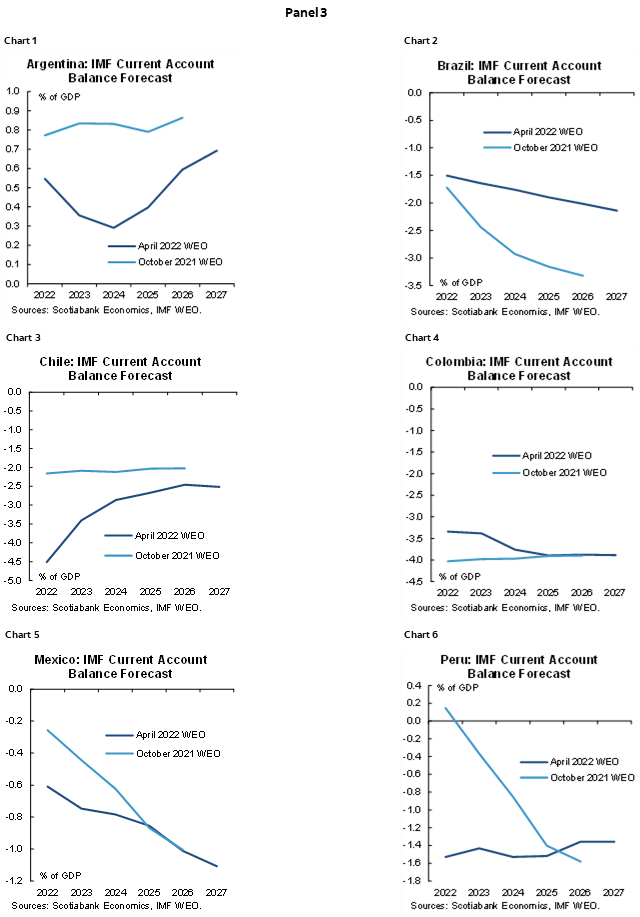

But external financing risks cannot be entirely dismissed. Higher current account deficits resulting from the combination of weaker external demand and unfavourable terms-of-trade shocks that lead to increased external debts warrant close attention. Panel 3 (below) shows IMF projections of current account balances in the Latam region. Projected current account deficits have widened (or in the case of Argentina, surpluses narrowed) across the region. Brazil and Colombia are exceptions, where the Fund staff now forecast smaller deficits as compared to six months ago, likely reflecting the aggressive tightening of monetary policy by the BCB that is expected to squeeze demand in Brazil and favourable terms-of-trade shocks from higher prices for the agricultural and energy exports of both countries. In any event, though current account deficits have widened in much of the region, there is no immediate cause for concern provided global financial markets remain orderly.

The outlook is far bleaker elsewhere. In developing countries heavily dependent on imported foodstuffs, the rise of commodity prices resulting from Russia’s invasion represents both a financial and social threat. Lacking the financial capacity to pay for food imports, they face growing shortages, worsening poverty, and rising social protests. Countries buffeted by pandemic shocks and now confronting adverse terms-of-trade effects could animate renewed concerns of debt distress. Key Latam countries are not at risk. However, sovereign debt problems elsewhere could elevate risk premia with respect to capital flows, with potential spillovers on international financial stability and the ability to finance current account deficits.

Such concerns have been a perennial talking point at past Spring Meetings, at which collaborative efforts are made to minimize the threats to shared prosperity. Russia’s war on Ukraine and the possible bifurcation of the global economy that may follow from it could impede these efforts going forward. In this respect, this year’s Spring Meetings may in the future be viewed as marking the high tide of the second age of globalization.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.