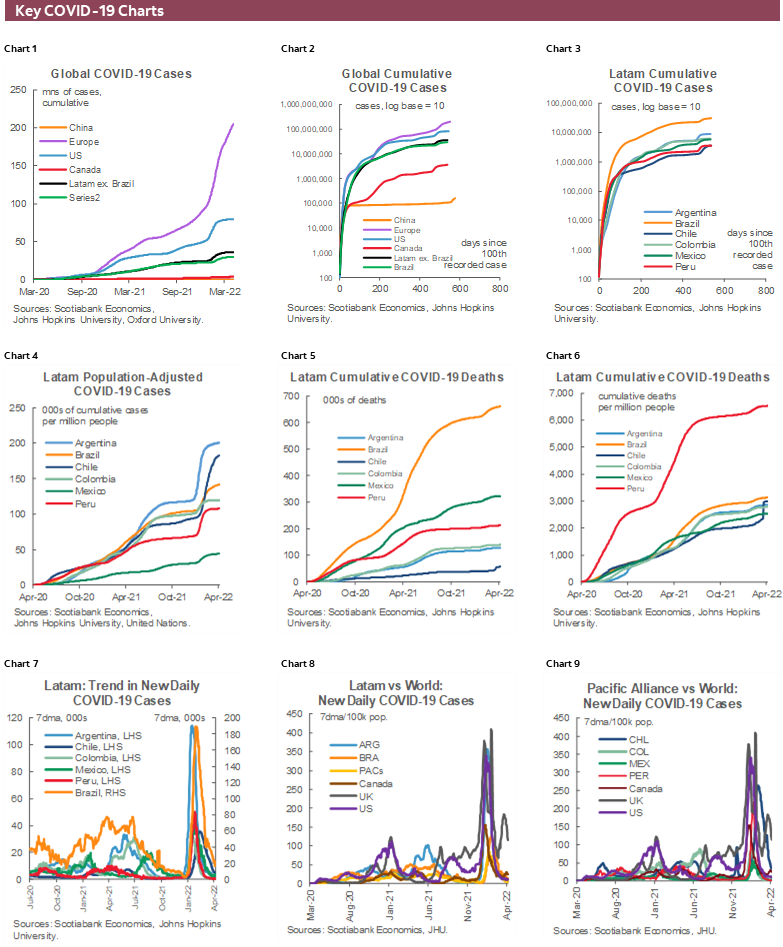

- Protests in Peru this week highlight the dynamic between rapidly rising prices and the importance of controlling inflation. While the protests in Lima were triggered by rising fuel costs, steep increases in food prices could foment social discontent going forward.

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has already led to higher world prices for cereal grains and other key agricultural products. The expanding sanctions regime and the threat of counter sanctions creates the potential for further hikes in food prices.

- Price pressures stemming from these supply-side shocks highlight the impact of inflation on households’ purchasing power, both in terms of real income and desired real balances of financial assets. In this respect, the return of the real balance effect is likely to reinforce the need for independent, inflation-targeting central banks.

Social protests in Peru incited by rising fuel prices naturally raise questions as to how the situation will evolve in coming days and whether the unrest seen on the streets of Lima might spread elsewhere in the Latam region. But the protests also focus attention on what economists refer to as the real balance effect and what it implies for economic performance over the medium term. In fact, you can expect to read a lot more about this effect in coming weeks as inflation erodes households’ real purchasing power.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine enters its second month, attention increasingly focuses on the mounting evidence of war crimes perpetrated on Ukraine civilians. The moral outrage that the atrocities has justifiably generated will inevitably lead to additional sanctions, some of which have already been announced. And those sanctions will, in turn, inevitably animate promises of retaliation by Russia, including, ominously, the spectre of restricting exports of wheat and other cereals as well as edible oil crops. It would be folly to discount such threats.

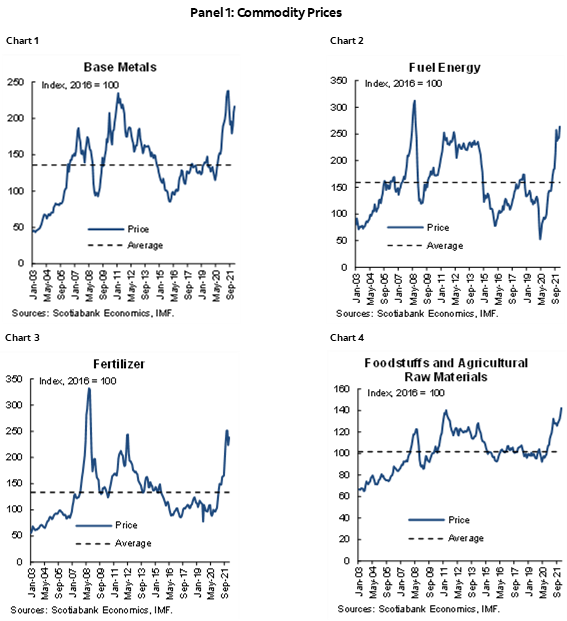

As shown in the chart panel below, global commodity prices had been trending up even before the Russian invasion. The realization of geopolitical risks has pushed these prices higher. And as has been argued in the past, the terms of trade effects of these developments are unlikely to be the same across all Latam countries. Moreover, the distributional consequences within a particular country could be significant. Employment and wages in mining may rise with higher base metal prices, for example, but increases in fuel energy costs and the price of foodstuffs could affect those not in the mining sector. A report by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the UN released April 8 drives that point home. The FAO note that world food prices spiked in March to their highest level ever.

The use of foodstuffs as a strategic weapon, the deployment of which would disproportionately harm the world’s poor, could have potentially large impacts on household consumption and exacerbate the tensions that this week led to protests on the streets of Lima. As noted above, one reason for those impacts is that higher prices reduce the real value of households’ holdings of liquid financial assets.

This effect is separate from the erosion of real income (a flow variable), which obviously cannot be dismissed. In theory, if all prices are rising at the same rate, workers could demand higher wages to keep pace with the increase in the price level, such that real wages are unaffected by inflation so the economic effects are transitory. Though, in practice, getting those higher wages often entails costly strikes and an increase in labour militancy. This is because the price of a firm’s output may not be rising at the same rate as the cost of households’ consumption baskets so that granting wage increases implies lower profits.

In contrast, the real balance effect affects a stock variable with impacts that persist through time. These inter-temporal effects are typically explained in terms of a desired level of real balances of liquid assets that households wish to hold. With real balances defined by liquid assets divided (or “deflated”) by the price level, an inflation shock that raises the price level reduces actual real balances below the “desired” level. This shortfall in actual real balances relative to the desired level triggers an adjustment process that unfolds over time, one that requires a modification to planned consumption. In short, it requires that consumption be reduced relative to income until such time as equilibrium real balances are restored. That squeezing of consumption implies that, other things equal, aggregate demand is lower than would otherwise be the case, with clear implications for growth.

For central banks intent on delivering on their price stability commitments, this adjustment process is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it contributes to the goal of disinflation. In the simplest possible model, if the central bank doesn’t accommodate the inflation shock, the decrease in consumption associated with the real balance effect will help dissipate price pressures, facilitating a timely and orderly return of inflation to target. On the other hand, uncertainty with respect to the mechanics of the real balance effect—the size of households’ “desired” real balances, the speed at which households aim to restore real balances, etc.—increases the risk of miscalculation in the calibration of monetary policy.

Unfortunately, the risk of miscalculation may be especially pronounced in the current circumstances. This is because the current inflation is, if not sui generis, unlike any episode in the past three-quarters of a century. The global pandemic has resulted in a series of severe supply-chain disruptions, to which Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has added. And because supply-side shocks differ from aggregate demand shocks in both raising prices and reducing output, central banks attempting to engineer a soft landing (reducing growth to bring down inflation while avoiding a recession) have less margin for error. Central banks acting too aggressively could tip the economy into recession, leading to higher unemployment and possibly fomenting social discontent; acting too slowly, however, or setting policy that is insufficiently restrictive, risks an acceleration of inflation as inflation expectations become unmoored.

Getting policy right in such circumstances is clearly a difficult challenge, one that is complicated by the legacy of the pandemic. In this respect, current price pressures may, to some degree at least, reflect the adjustment effect of real balances being above “desired” levels. It is possible, for example, that actual real balances are above desired levels owing to the extraordinary fiscal response unleashed by the pandemic, specifically assistance measures designed to insulate households from job losses. Combined with a strong labour market that reduces the probability of future unemployment, consumption spending on goods (as opposed to services) could thus be a manifestation of households adjusting real balances back down to pre-pandemic levels. And because of supply chain disruptions, this spending falls on highly-inelastic supply. It is little wonder then that prices have risen.

Needless to say, this excess real balances effect need not apply to all households in all countries, though that seems to be the inference from a recent Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco note with respect to the US. It certainly doesn’t apply to Latam households living at or below the poverty line. Such “hand-to-mouth” consumers effectively spend all that they earn. As a result, higher inflation that is not matched by increases in incomes pushes them further into poverty. Growing social discontent is a possible outcome. The plight of such households underscores the need for governments in the region to respond quickly and appropriately to the erosion of real purchasing power with targeted fiscal measures. In Chile, the government recently announced assistance to shield the most vulnerable from the effects of higher inflation. Meanwhile, in Peru, on April 7th, Congress approved legislation exempting a number of key staples from the 18% sales, including chicken, eggs, milk, meat, wheat, pasta and sugar. Our team in Lima expects the legislation to be signed into law with little delay.

For the avoidance of doubt, the need to protect the most vulnerable from the effects of inflation does not militate for “activist” monetary policy. In the past, governments may have responded by expanding the money supply in an attempt to quell economic discontent. However well-intentioned such efforts may have been, they ultimately ended in higher inflation and even greater economic dislocation.

For countries in the Latam region, the adoption of inflation-targeting regimes by independent central banks created an effective guard rail against such policy mistakes. The return of the real balance effect is likely to demonstrate the wisdom of that decision.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.