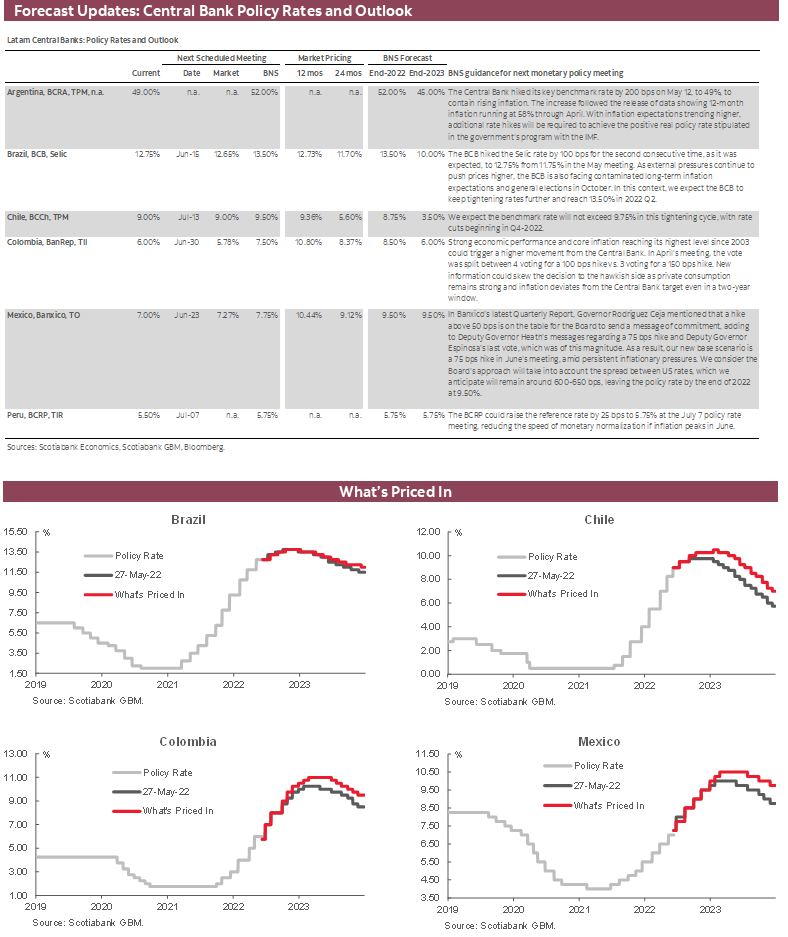

FORECAST UPDATES

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has now lasted more than 100 days, has led to increased concerns about global growth. With international organizations marking down their projections, a less favourable external environment would affect growth prospects in the Latam region. See the latest forecasts of Scotiabank’s regional economists in the forecast tables below.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- While Russian war aims have been considerably scaled back, the costs of the invasion have steadily mounted. These costs go beyond the horrific toll in terms of lives lost and property destroyed. Economic costs have also escalated.

- Higher inflation resulting from the invasion has already eroded real wages and reduced the purchasing power of savings. Many “hand to mouth” households, earning just enough to cover living expenses, have been pushed into poverty as prices of key foodstuffs have increased. The need for more aggressive monetary policy to combat higher inflation, meanwhile, increases the risk of recession.

- In this respect, as has been noted in previous editions of the Latam Weekly, the war has added additional uncertainty to an already uncertain environment, one clouded by the lingering effects of the pandemic on public health and the economy. Domestic political and policy uncertainty can increase the costs, either through risk premia on assets or in terms of the option value of waiting, as investment decisions are deferred.

- The war also threatens to produce a food shortage, as the Kremlin has conditioned grain and fertilizer shipments to the lifting of international sanctions. And while it is too early to say what the next 100 days of war will bring, the longer that it lasts, the greater the risk of long-term damage to the global economy.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

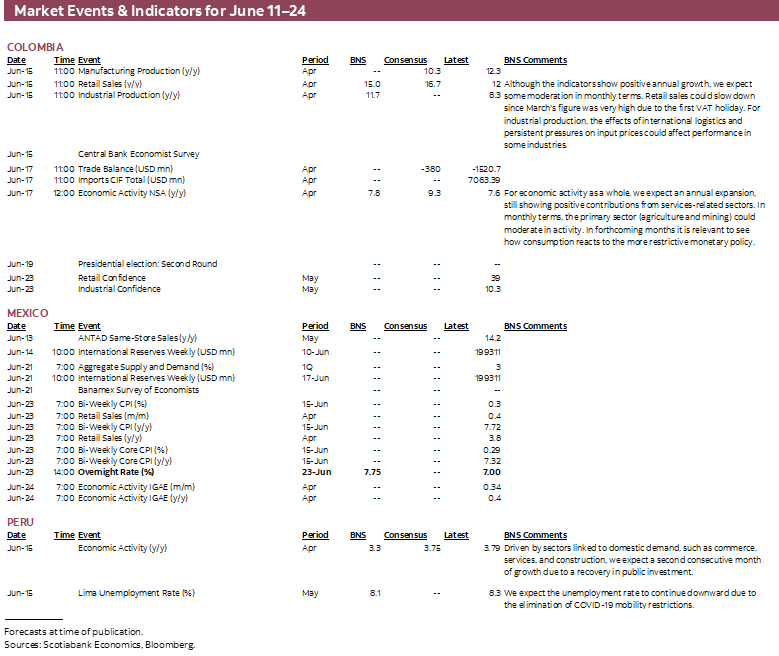

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period June 11–24 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: 100 Days and Counting

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- The Russian invasion has already exacted a devastating toll in terms of the lives lost and the property and public infrastructure destroyed. The destruction is appalling. But the war has also imposed significant costs on the global economy, largely in terms of higher inflation, which has pushed households into poverty, and the increased risks of policy miscalibration that could lead to recession. It has also generated additional uncertainty that weighs heavily on economic growth.

- The mounting economic costs of the Russian invasion coming on top of pandemic-related supply chain disruptions could pose a threat to the system of international trade and global finance—globalization. In the first instance, this scenario is driven by the need to find alternative sources for inputs, and in the case of Europe, energy security.

- Some scaling-back of global supply chains to enhance resiliency was likely already under consideration by many firms as the pandemic revealed the fragility of the status quo. The application of a rigorous sanctions regime by countries around the globe could hasten this process. This is because there is an implicit threat behind US statements that countries cannot benefit from a rules-based international order while shirking the burden of upholding that order.

LET THEM BE LOCAL

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has now passed the 100-day mark. In that time, the Kremlin’s objectives have been dramatically scaled back—from wholescale regime change to more limited territorial ambitions in the east of the country. In contrast, the human and economic costs of the invasion have escalated. The Russian army has been badly mauled by much smaller Ukrainian forces that can ill afford to sustain the losses from a protracted war of attrition. Thousands of combatants on both sides have been killed, many thousands more wounded. The civilian lives lost, and the wanton destruction of homes, factories and public infrastructure is staggering. History may well record that never before in the field of human conflict has so much destruction been done, in so short a time, on so little provocation.

The economic costs of the invasion have also mounted. Higher inflation resulting from commodity price shocks has already spread across the globe. And coming on top of earlier price pressures emanating from COVID-19 supply chain disruptions and strong demand fueled by lax monetary conditions and fiscal support to households and businesses, this additional inflationary shock has led central banks around the world to accelerate the pace of monetary rebalancing. In this context, the risk of policy “overshooting”, and the threat of recession, have increased. Unanticipated rises in the price level, meanwhile, have reduced real wages and eroded the value of savings through the real balance effect. Such responses could dampen consumption, though, in the case of Chile and Peru, access to pension fund withdrawals can be expected to temporarily mitigate the size of the effect for many households (i.e., those in the formal labour market).

Reflecting the convergence of these factors, two international organizations—the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—marked down their forecasts of global growth this week. Their revisions follow that of the International Monetary Fund, which lowered its projection of global growth in the April World Economic Outlook. While slower global growth would help cool price pressures coming from economic “overheating”, for the Latam region it also means lower external demand. That conjuncture was recognized by Chile’s BCCh in its decision to hike the policy rate.

At the same time, with the Fed now projected to raise rates more aggressively—joined by the ECB and other advanced country central banks—global financial markets have witnessed shifts in investor risk appetite that has led to a marked appreciation of the US dollar against many developing-country and emerging-market currencies. As Scotiabank’s team in Bogota note below, however, for some in the Latam region, higher commodity prices have limited currency depreciation. Nevertheless, continued dollar appreciation, possibly exacerbated by rising geopolitical tensions, would multiply the challenges faced by Latam central banks as local currency depreciation could stoke inflationary pressures through exchange rate pass-through effects.

In this respect, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has clouded the outlook, compounding the economic costs. And, to put it mildly, in such circumstances, additional political and policy uncertainty is “unhelpful.” The costs of such uncertainty can be measured in an uncertainty premium on the exchange rate (see the Colombia country notes). Or it can show up in terms of lower investment. This is because uncertainty increases the option value of waiting, particularly with respect to investment decisions. Firms may delay long-lived projects, waiting for clarity on what the future policy regime will be. In Mexico, Scotiabank experts note that investment has been the weak link in the recovery, possibly reflecting uncertainty with respect to the policy environment.

A more menacing and insidious cost of the war is the growing threat of hunger and poverty as basic foodstuffs become more expensive. This week also saw increasing alarm over the consequences of Russia’s invasion from the de facto embargo of Ukrainian cereals and other crops. With Black Sea ports blocked and storage silos already full from last year’s harvest, Ukrainian farmers who have not already completed their spring seeding could understandably balk: why incur the expense of planting if the harvest is destined to rot on the farm? Latam countries that are net food importers face a negative terms-of-trade shock, one that could foment social unrest as poverty increases. This possibility has already led to a range of measures across the region to cushion the blow on the most vulnerable. Such measures can only be partially effective. The situation is more dire in many poorer developing countries, however. Absent action to resume shipments and empty storage silos, a global humanitarian crisis looms large. Yet, attempts to forcibly open the Black Sea ports could lead to an escalation and widening of the conflict.

Accounting for the costs of Russia’s invasion would not be complete without consideration of the effects of sanctions and the potential implications on global trade and integration. Before the onset of hostilities, the sanctions imposed by the US, EU, UK, Canada and others were intended to give the Kremlin pause—to reconsider the path of war. They failed in that regard. And while the Russian ruble crashed as G7 governments froze the international reserves of the Russian Central Bank, it has since appreciated. This is explained, in part, by a draconian regime of capital controls and higher interest rates; in part by the widening of the current account as the increase in world oil prices more than compensates for lower export volumes. That outcome was readily foreseeable: with both supply and demand inelastic in the short run, an embargo of Russian oil was bound to increase revenues. But the rebound of the ruble does not necessarily imply that sanctions are ineffective. Russians are already feeling the sting of sanctions as firms curtail production for want of needed inputs. Higher unemployment and greater poverty are likely.

If anything, the apparent resilience of the ruble is likely to lead to an expansion of the sanctions with increased risks to the global economy. Moreover, sanctions are now a permanent feature of the global landscape, at least for the duration of the conflict. And additional costs from the sanctions will come from the US decision to block frozen assets from being used to service Russia’s foreign debt which is likely to trigger a default, though it could have unintended collateral damage to others (as investor risk appetite is further skewed to safe assets).

It is also clear that the EU’s energy dependence on Russia will end. Coal is the first, oil will follow. Gas shipments will take longer to wean from, given the time required to build the infrastructure needed to import LNG from other sources.

In the meantime, the US Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, has made it abundantly clear that countries that do not support, or half-heartedly support, sanctions against Russia will come under increased scrutiny. Her message, riffing off an earlier editorial by Canada’s Chrystia Freeland, is that countries cannot both benefit from the international rules-based order that has made globalization possible while refusing to help defend the system.

Yellen’s admonition and the potential economic and financial fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlight the risks to globalization. Even before the onset of hostilities, COVID-19-related supply chain disruptions, which were magnified by the highly (some might say “hyper”) granular division of production and reliance on a few—in the limit, sole—suppliers, may have led some to rethink the benefits of globalization. The spread of sanctions, counter sanctions and financial penalties may likewise lead to a revaluation and eventual reorientation of trade flows around the globe.

It would not be the first time that the benefits of globalization were questioned. Writing at the nadir of the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes argued:

“Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel—these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.”

Keynes’ “let them be local” rallying call was a response to the propagation of economic collapse through financial and trade channels at the outset of the Depression. In time, however, he recanted. With sound policy frameworks and strong domestic and international institutions—the foundations of the rules-based international economic order—countries could, he realized, reap the gains from trade without unduly sacrificing sovereignty or exposing their economies to devastating external shocks.

While it is too early to know the costs to the global economy from the next 100 days of war, we can hope that policymakers across the globe come to the same realization. Though some retraction of global supply chains may be necessary to enhance economic resiliency, a wholesale retreat from globalization would not serve anyone’s interest. That observation should provide some grounds for optimism. But wars are easy to start, difficult to end. And as Fredrick the Elector sagely observed to a courtier: “it is easy to take a life, but can you give it back?” If the process of de-globalization begins, it may not be so easy to reverse.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Marginal Additional Hikes in the Benchmark Rate, but Conditional on Moderation in Inflation

Jorge Selaive, Head Economist, Chile

+56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

COVID-19 SITUATION IN CHILE

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has continued to increase in recent days. The test positivity rate rose to 13%. For now, however, occupancy rates of ICU beds and COVID-19-related death rates are stable at low levels. Meanwhile, the vaccination campaign has reached 92.4% of the eligible population. The rollout of booster (third) doses continues—reaching 14.7 million people—and the new booster dose (fourth) is in progress—with 7.8 million people covered. Overall, mobility is stable at high levels in June, which will continue supporting the economic activity, mainly services.

ECONOMIC ACTIVITY REMAINS RESILIENT, SUPPORTED BY FORMAL JOB CREATION

On Monday, May 30, the statistical agency (INE) announced that the unemployment rate for the three months ending in April fell to 7.7%. The drop from the previous three-month period reflects employment growth, with 38 thousand added to payrolls, that exceeded the 36 thousand increase in the labour force.

There was good news for formal employment, which closed the gap with respect to its pre-pandemic level. The incentives given by the government since last year through the Emergency Family Income (IFE), which continues through the end of the year, likely contributed to this recovery. At the sectoral level, jobs were created throughout the economy, except for construction.

On Wednesday, June 1, the central bank released monthly GDP for April, which expanded 6.9% y/y (-0.3% m/m), in line with the labour market performance. Although activity continued to moderate, especially in the commerce sector, it was supported by the recovery of mobility and the around USD 4.5 bn of liquidity still available in households resulting from pension withdrawals and fiscal aid (chart 1), complemented by a favourable rate of job creation.

In this context, the central bank adjusted its forecast for the 2022 GDP growth from 1.5% to the range 1.5–2.25% in June’s Monetary Policy Report. In its report, the central bank recognized that the speed at which the economy is slowing is less than expected. The component that exceeded the BCCh’s expectations has been consumption, though we have observed that private investment has also shown somewhat greater resilience, especially with respect to machinery and equipment.

We maintain our forecast of GDP growth of 3% for this year, well above the 1.5% reflected in most surveys. However, given the continued resilience in the economy, we anticipate a convergence of market expectations towards our forecast in the coming months, dispelling expectations of an abrupt adjustment in activity.

HIGHER INFLATION, HIGHER RATES

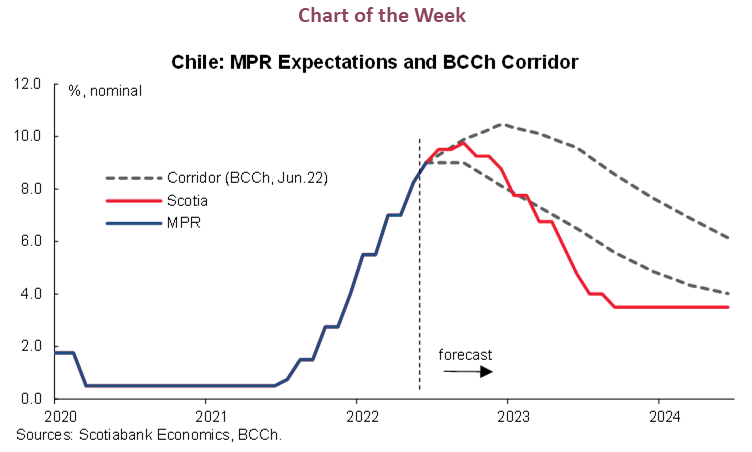

On Tuesday, June 7, the central bank (BCCh) increased the benchmark rate to 9.0%, in line with market and our expectations. The central bank anticipates further increases in coming meetings. With this, we expect a terminal rate of around 9.75% in this adjustment process.

In our view, cuts in the monetary policy rate (MPR) could take place in the December 2022 meeting (chart 2) if inflation starts to ease, which is highly conditional on the external scenario, the exchange rate, and to a lesser extent on the capacity gap at this juncture.

For now, consumer prices continue rising, reaching 11.5% y/y in May. On Wednesday, June 8, the statistical agency (INE) released the May CPI, which increased 1.2% m/m, largely explained by food and transportation. The CPI excluding volatile components increased 0.9% m/m, similar to that of April (1.1%) and still high in historical perspective. The adjustment of prices at the retail level and by service providers, together with the second-round effects, show no signs of slowing down. Furthermore, a worrying acceleration is observed in the price adjustments of goods.

Given the persistence and second-round effects observed in recent months, we have adjusted our inflation forecast for the end of December 2022 upwards, from 8.4% y/y to 10.2% y/y. In the coming months, we will most likely see new second-round effects, mainly in services, which will augment the effects of higher local fuel prices in the short term.

A LOOK AHEAD

In Chile, there are no relevant macroeconomic indicators for the fortnight ahead. However, the constitutional convention continues to work on the draft of the new constitution, voting on the proposals of both the harmonization commissions and transitory norms. For now, the discussion focuses on the quorums needed to make future changes to the constitution. It should be noted that the work of the convention will end on July 5. For its part, the central bank will release the minutes of the June monetary policy meeting on June 23.

Colombia—Colombian Assets Amid International Volatility and Political Uncertainty

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9166 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Maria Mejía, Economist

+57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

maria1.mejia@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Senior Economist

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9400 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

In 2022, two years after the market dysfunction that accompanied the onset of the global pandemic, financial markets still face high volatility amid uncertainty over the transition to less stimulative monetary conditions by major central banks. This shift in policy stance, which is needed to combat inflation, has motivated investors to seek out safe assets, leading to a dollar strengthening, especially against many developed countries’ currencies. In the case of some emerging markets currencies, this effect has been moderated owing to higher commodity prices. That said, we have seen large movements in the yield curve of many emerging markets economies.

In the case of the USDCOP, the currency has regularly exceeded 4,000 pesos/USD since the start of 2022, despite much higher high oil prices, diverging from long-term fundamentals. The challenging environment of higher international rates, the loss of investment grade in 2021, and the uncertainty coming from the congressional and presidential elections are perhaps the most important influences on COP behaviour. After the March 13th congressional elections, which decided the composition of the new Congress, the exchange rate traded on average around 3,880 pesos/USD. The elections were the first signal that Colombia’s political status quo would continue. As the date for the first round of the presidential elections approached, exchange rate volatility increased and the peso momentarily reached the 4,100 pesos/dollar level—the highest level so far this year. According to our model, high volatility and the strong upward trend were due to the risk premium for the presidential elections. In fact, our model puts the political uncertainty premium around 250 (meaning the exchange rate traded 250 pesos/USD above its fundamental value).

On Tuesday, May 31, the USDCOP presented probably the largest daily appreciation in history, moving from 3,933 pesos on Friday to 3,770 pesos following the election (chart 1). The election was the main explanation for this movement, as the market took the result as the second confirmation of the likely economic status quo. However, in our opinion, the USDCOP is far from consolidating a downward trend. The presidential runoff election is a close call, and it is still unclear how the two potential presidents, Rodolfo Hernandez or Gustavo Petro, both of which represent a change of politics in Colombia, will deal with a very divided Congress in passing important and urgent economic reforms.

Given this uncertainty, we do not think that the exchange rate is likely to return to pre-pandemic levels in the 3,500 pesos/USD or lower range) on a consistent basis over the medium term. Several factors support our view. The fiscal imbalances resulting from the pandemic and the loss of investment grade status continue to weigh on the currency; meanwhile, it is difficult to reduce the external deficit in the current international context. In addition, inflation will remain the most important challenge to tackle in the short run, implying that central bank tightening, a stronger US dollar, and volatile international risk appetite can be expected.

In the local fixed income market, while rates eased 30 bps, on average, after the first round of elections, we expect monetary policy fundamentals will continue to push the fixed income trend up in the medium-term, consistent with the transition to higher monetary policy rates. The central bank (BanRep) is likely to reach the terminal point of its tightening cycle by July at 8.5% and stay at this level for about a year. That said, the short end and the belly of the curve will remain under pressure owing to macro fundamentals.

The most material risk to the curve, however, is from international monetary policy. In the US, long-term real rates are increasing as the recent calls for future higher rates have moderated breakeven inflation, and these dynamics negatively impact emerging-market assets. International monetary policy developments thus remain a key issue for local assets, while the presidential election could yet lead to higher volatility in the short run, particularly as uncertainty about future politics remains. The USDCOP is not expected to trade consistently below 3,700 if there is no news about fiscal sustainability, while the COLTES curve will continue to be affected by Federal Reserve.

Mexico—Investment Story: It’s Complicated

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

+52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

Arguably the weakest link in the Mexican economy has been soft investment ever since the Texcoco airport project was cancelled back in 2018. The strongest investment rate for Mexico in the past three years would still rank as the weakest in the previous decade (chart 1). From averaging 23% of GDP in the 2010-2017 period, total investment has fallen to an average of 21% in 2018–2021. Within the Latam region, Mexico’s 2018–2021 investment rate is in the middle of the pack (chart 2). But even with higher investment rates, it still underperformed its regional peers in terms of growth.

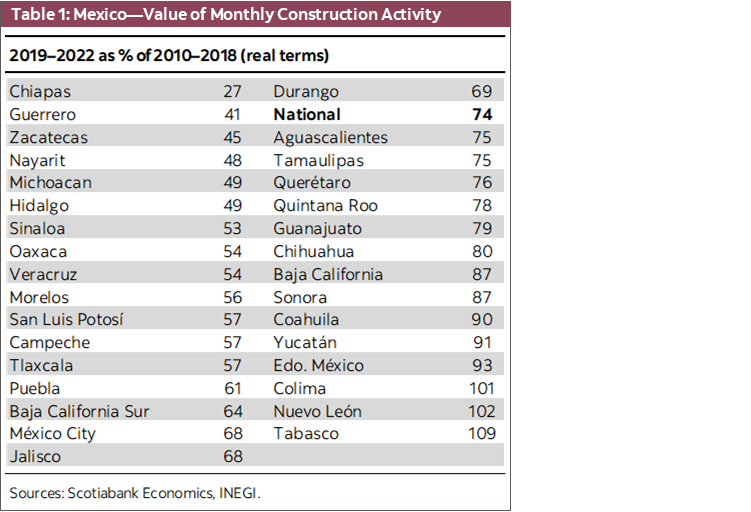

Within this weak aggregate story, however, there are some bright spots. Investment has held up well in manufacturing power-house states where logistics and, to some degree, near-shoring trends are helping boost construction and investment in general. In addition, some states in the south of the country are seeing construction activity boosted by the government’s priority projects—such as the Mayan Train and the Dos Bocas refinery. On the flip side, states such as Guerrero and Chiapas that have not been integrated into Mexico’s export-oriented manufacturing supply lines have suffered from a severe investment drought (table 1).

What to expect going forward? To some degree, we think the outlook is more of the same, although we anticipate a short-term bounce in investment. Mexico’s population growth dynamics (the labour force is expected to grow close to 1% per year for the coming 10 years) mean that, with the almost three years of investment contraction, companies’ productive capacity has fallen (chart 3). With the higher consumption that would accompany population growth, this means that firms would have to ramp up investment to maintain their market shares. We anticipate that investment will pick up as we head into the second half of 2022 and will likely remain relatively robust into the beginning of 2023. Beyond that, there are many moving parts, including US growth uncertainty, rising interest rates, and the 2024 Mexican and US presidential elections. In this respect, while we expect that total investment as a share of GDP could approach 22% in 2022 and 2023, a more lasting pick-up will depend on the domestic political and economic environment, in which the 2024 election will play a key role (chart 4).

Peru—If Only Peru’s Politics were as Good as its Fiscal Accounts

Guillermo Arbe, Head Economist, Peru

+51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Mario Guerrero, Deputy Head Economist

+51.1.211.6000 Ext. 16557 (Peru)

mario.guerrero@scotiabank.com.pe

The general feeling in Peru is that things are settling down to an overall, albeit rather reluctant, acceptance of living with an economy that meshes the good (macro balances) with the bad (inflation), within a persistently unsettled political status quo.

The most refreshing aspect of Peru’s economy is probably the fiscal deficit, which came out at 0.9% of GDP to May on June 6 (chart 1). Based on this, we are revising our 2022 fiscal deficit forecast, currently at 2.0% of GDP, to 1.5%. This is our second adjustment in as many months. Initially, we had forecast a 3.0% of GDP deficit. Peru’s fiscal situation is, evidently, very strong. In early 2020 the fiscal deficit had peaked at 8.9% of GDP and there was a general idea that it would take the better part of a decade to get it back into fiscal rule territory of 1% of GDP. And yet, here we are only two and half years later. Even if the fiscal deficit begins to rise during the remainder of 2022, as we expect, it should still stay significantly ahead of the official fiscal rule schedule of 2.5% of GDP in 2022 before descending towards 1.0% in 2026.

Fiscal accounts are being handled much better than other areas of governance, mainly because the Ministry of Finance and the tax administration agency have operated independent of direct political interference. And fiscal revenues continue to be on fire. Yearly income tax revenue to May rose an impressive 42% y/y, and sales tax revenue was up a hefty 11.9%.

The strength of the fiscal accounts gives Peru’s authorities plenty of room for an expansionary policy or for measures that seek to compensate for rising inflation. The government has already established a stabilization fund for certain fuel products, as well as tax benefits for a number of staple goods. More tax benefits of this nature could occur. Even so, the fiscal picture is not likely to change unless the government begins to spend in earnest. Public investment, in particular, is dragging (chart 2). This may continue in 2023, as new authorities will be elected this coming October. This changeover normally causes a discontinuity in the investment schedule.

Our sentiment for GDP growth is a bit more lukewarm. One can’t complain about growth so far: 3.8% y/y in Q1, and likely a similar level in April. The question is how long this will last. There are two clear growth leaders in y/y terms: exports, and sectors that are rebounding after last year’s lockdown, including entertainment, hospitality and education. To a lesser extent, consumer demand sectors are also performing well. In contrast, last year’s driver of growth, construction, is lagging significantly, as is mining.

Exports volume growth is now being driven more by agroindustry, oil & gas, and textiles than by mining. All three export sectors are largely independent of domestic issues and should continue doing well. In contrast, the post-COVID-19 rebound in entertainment, tourism, education, and restaurants should eventually peter out, although not quickly. Except for restaurants, these sectors will grow off a low y/y base for most of 2022.

The one thing that could hamper this performance of domestic goods and services is rising prices due to inflation. Inflation is an issue for all consumption growth. Real household incomes are still 16% below pre-COVID-19 levels, even as employment has recovered, mainly because of inflation. That said, a large segment of households will have access to pension fund withdrawals, which bolstered consumption in the past.

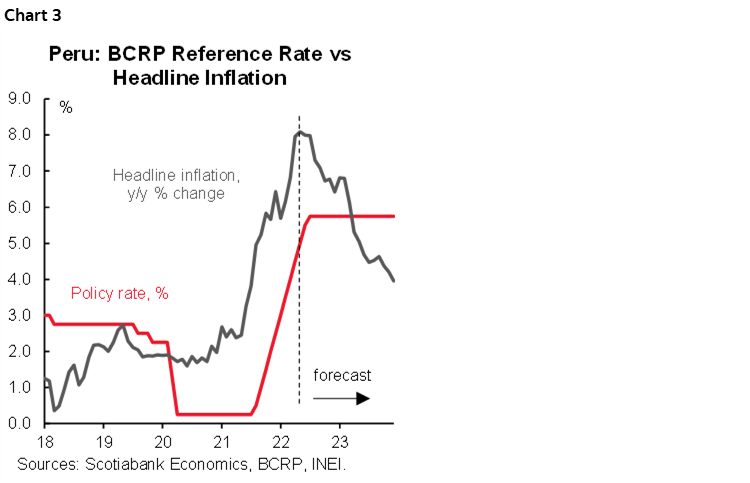

Speaking of inflation, the BCRP raised its reference rate by 50 bps to 5.50% on June 9, as we and the market expected (chart 3). Now the question is what the BCRP will do going forward. We expect one more 25 bps increase in July, and then stable at 5.75% from then on. The market expects a bit more, between 6.0% and 6.5%. There are reasons that justify a more aggressive BCRP. Twelve-month inflation to May is 8.1%, and inflation expectations have soared to 4.9%. Thus, the real reference rate (which is measured versus inflation expectations) is just barely positive. All this amid a backdrop of central banks aggressively raising rates globally.

And yet we hesitate to be more aggressive in our forecasts, just as we believe the BCRP must be hesitating in being more aggressive in its policy. The main reason is that inflation could be very near its peak. Outside of oil prices (a very important exception, and something we are quite concerned about), most global prices that are important for Peru seem to be stabilizing. At the same time, we continue to fail to identify domestic sources of inflation. If the BCRP shares our view of things, then it could very well decide that the reference rate at 5.75% would be high enough.

A final word on politics, just to start the weekend on a fun note. As we mentioned above, things appear to be settling down, even as the circle of corruption information and investigation surrounding President Castillo tightens. New information has emerged concerning malfeasance at the Ministry of Transportation, with reach into President Castillo’s inner circle. At the same time, there appears to be a shift in the political mood away from impeaching President Castillo, and towards holding early presidential and congressional elections. Not that we’re anywhere close to seeing that happen. In a word, political uncertainty is the status quo and businesses appear to be learning to live with it.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.