FORECAST UPDATES

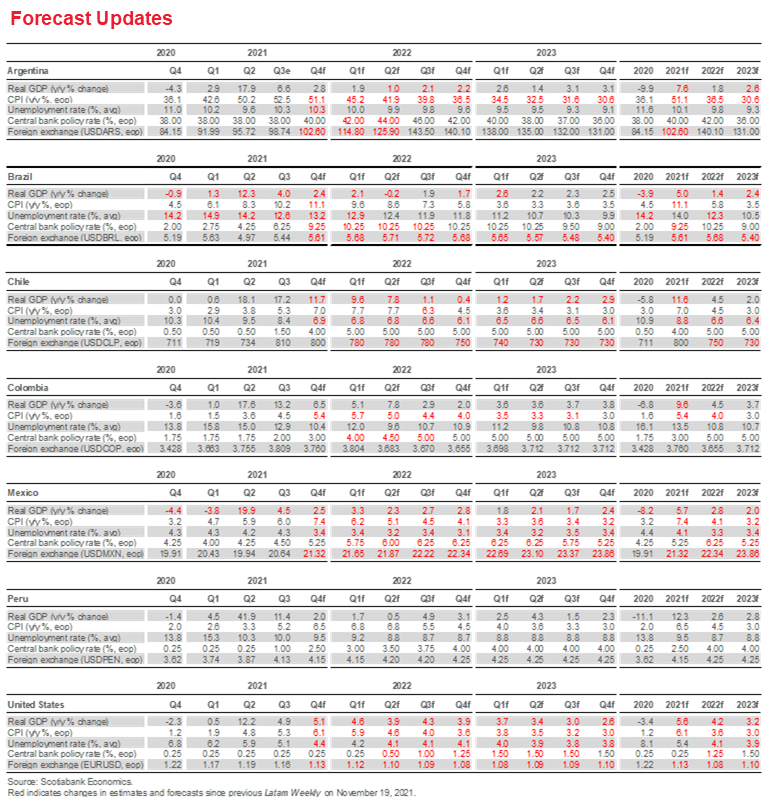

- Upside inflation surprises have led to forecast revisions across most of the Latam region. In Mexico, growth has been revised down while inflation has been marked up. See the full range of revisions in the Forecast Update table below.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- Output is back to pre-pandemic levels in most countries, and strong growth should carry over into 2022. However, inflationary pressures remain a threat to central banks’ price stability targets.

- Against this background, critical policy challenges confront monetary and fiscal authorities in 2022. Governments will have to scale back the extraordinary policies introduced in the pandemic to ensure long-term fiscal sustainability. Central banks will have to continue rebalancing monetary conditions to contain inflation.

- Looking ahead, central banks with floating exchange rate may confront the “fear of floating,” the consequences of sharp currency depreciations, as the US Fed begins to tighten policy.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

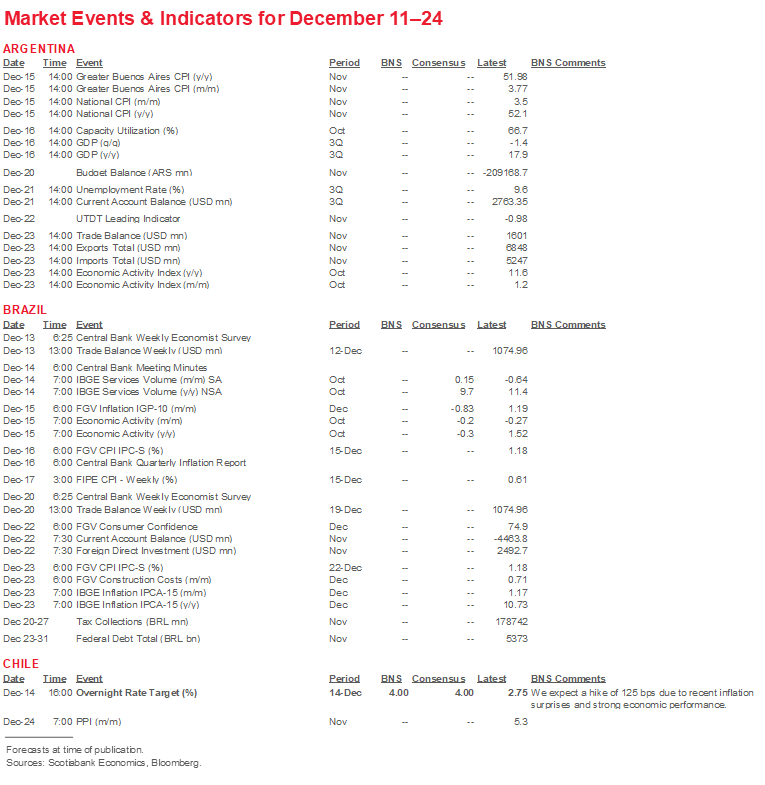

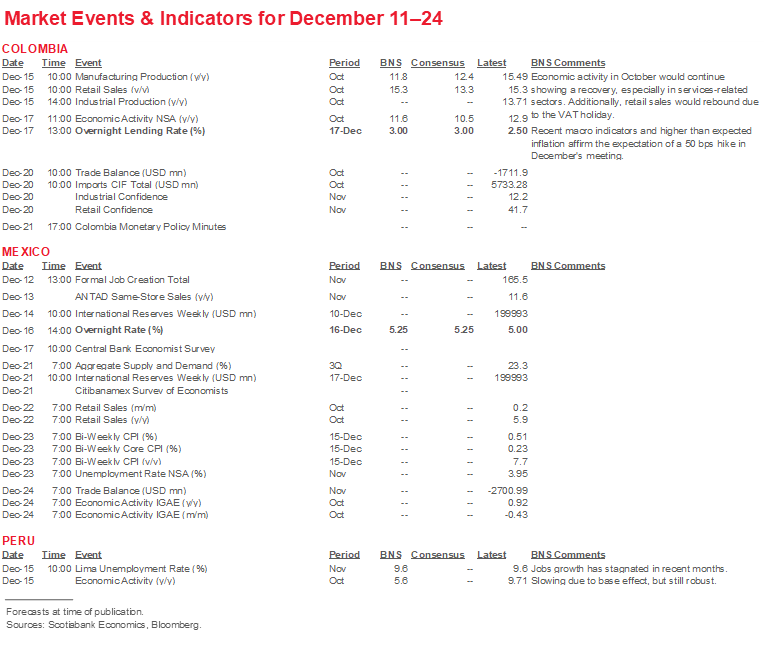

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period December 11–24 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: Fears of Floating?

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Economic recovery has taken root across the Latam region. Output has returned to pre-pandemic levels in most countries and strong growth should continue into 2022.

- But important policy challenges lie ahead. Extraordinary policy introduced in the pandemic will have to be scaled back to ensure long-term fiscal sustainability. And inflation poses a serious challenge to inflation-targeting central banks.

- In 2022, monetary may be complicated by the “fear of floating,” arising from sharp currency depreciations. While such concerns are not necessarily warranted by current conditions, neither are there grounds for complacency.

A JANUS-FACED LOOK AT THE CONJUNCTURE

As 2021 draws to a close, it is a good time to review where Latam economies have been and what lies ahead. This Janus-faced approach should provide a useful reference with which to assess risks going forward. The starting point for this exercise is the latest forecast updates made by Scotiabank economists in the region.

LOOKING BACK

A look back leads to the comforting conclusion that economic recovery has taken root across the region following the contraction in 2020. Output has already returned to pre-pandemic levels in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru, while Mexico is expected to recoup the output losses incurred in the pandemic much more slowly over the forecast horizon. And for most of the region, strong growth going into 2022 should provide a solid foundation for sustained expansion.

This propitious outlook stands in contrast to the uncertainty that prevailed only a few months ago as robust growth in early 2021 slowed sharply with the emergence of the more virulent delta variant of the COVID-19 virus. Economic activity subsequently picked-up as mobility restrictions were eased and individuals and firms adapted to lockdowns, sustaining consumption and production by changing behaviours and operations. This adaptive response is encouraging in that it is consistent with increased resilience to possible future setbacks. But while Latam economies adjusted to the COVID-19 virus, another threat emerged.

Inflation has risen steeply across the Latam region. While some increase in price pressures was widely expected given that inflation had been suppressed by the contraction in economic activity in 2020, inflation has surprised on the upside. Moreover, the spike in inflation has raised concerns that price pressures may become embedded in inflation expectations, which could propagate ongoing inflation through the legacy of wage-price backward indexation inherited from the region’s high-inflation past. In turn, if inflation expectations become unmoored from inflation anchors, the credibility of central bank commitments to price stability could come under threat.

To prevent the loss of the nominal anchor, central banks with inflation-targeting frameworks have begun to rebalance monetary conditions. Key policy rates have been raised and further increases are coming. Despite these increases, however, policy rates remain negative in real (inflation-adjusted) terms in most countries. And as Scotiabank’s team in Lima notes, the monetary policy real interest rate rose for the fifth consecutive month, but remains in negative territory, at -1.2% in December after the decision. In Peru, policy rate increases, which raise the cost of borrowing, have been supplemented by the introduction of quantitative measures—increases in reserve requirements—to contain credit expansion.

FACING THE FUTURE

Looking ahead, further monetary policy rate hikes depend on the persistence of inflationary pressures and the pace at which growth closes negative output gaps or opens positive (inflationary) gaps. A key consideration here is the pace at which supply-side bottlenecks are cleared. The longer that these disruptions remain (or become more widespread), the greater the risk that inflationary expectations will be revised upwards. And while enormous uncertainty remains with respect to this issue going into 2022, Scotiabank economists expect inflation rates will gradually return to target ranges over time.

The growth outlook, meanwhile, hinges on several factors. Economic recovery in the region has been driven by external demand, with commodity exporters especially having benefited from higher prices for their goods, which historically have been associated with stronger real GDP growth in Latin America. In this respect, the region’s medium-term outlook remains heavily dependent on global economic prospects, which remain tied to the progress made against the pandemic. As 2021 ends, the spread of the omicron variant clearly warrants close monitoring.

Going forward, domestic demand is likely to be an important growth driver as our economists in Mexico City highlight in the Mexico country update below.

POLICY CHALLENGES AND THE FEAR OF FLOATING

As the new year begins, monetary and fiscal authorities across the Latam region face key challenges. Monetary and fiscal policy measures introduced across the region have supported consumption and likely prevented a spike in delinquency rates and business bankruptcies by preserving firm-specific “relationship capital” between a firm, its workers, and its suppliers. This intangible capital is the web of connections and knowledge that allows a firm to operate at a high level of efficiency. The loss of these connections and this knowledge could lead to economic scarring that depresses long-run potential output growth.

Yet, however beneficial they have proven to be, extraordinary policies are not sustainable indefinitely. And with global expansion powering external demand, and private domestic demand coming back onstream, policy settings calibrated for extraordinary circumstances will have to be dialed back.

A prudent unwinding of fiscal measures would have a salutary effect, reassuring international investors and domestic savers of government commitments to sustainable public finances. Governments in the region have already laid out plans to restore fiscal positions; in Colombia, as our experts in Bogota highlight in the country notes below, important reforms to ensure long-term fiscal sustainability will have to be passed in the new year, making the upcoming elections a potential source of uncertainty. Meanwhile, the vicissitudes of erratic policymaking in Peru have contributed to large capital outflows by domestic residents, as Scotiabank’s team in Lima highlight (see discussion below).

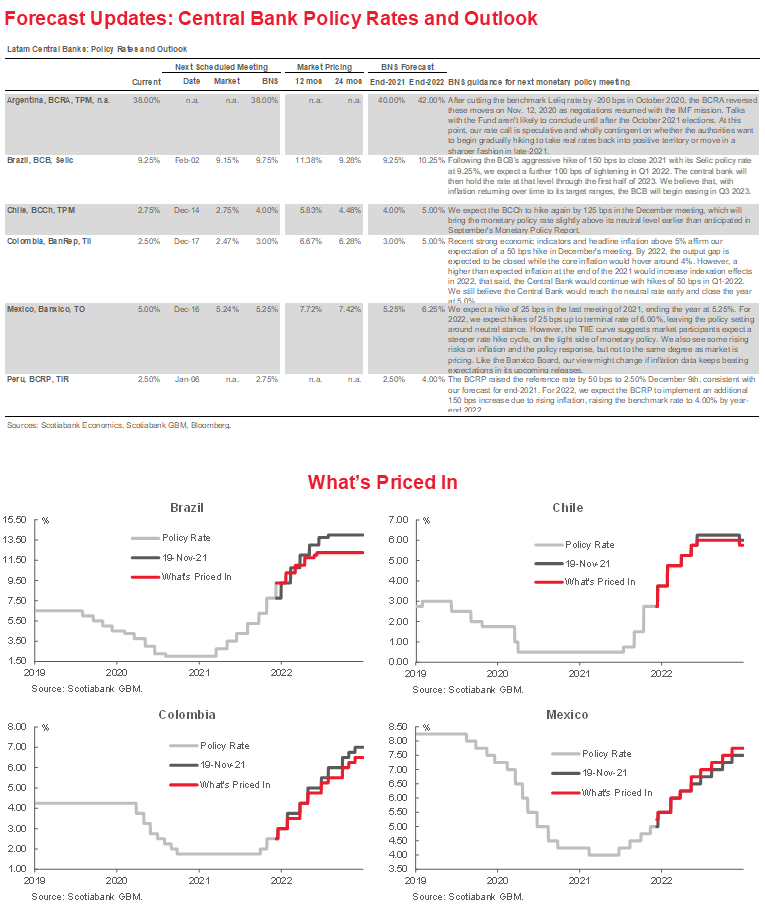

For monetary policy, the immediate priority is the rebalancing of monetary conditions to contain growing inflation risks. As their inflation forecasts imply, Scotiabank’s regional economists expect Latam central banks to succeed; in this respect, 2022 will be the year in which the question of whether inflationary pressures are temporary or persistent is answered. While inflation-targeting central banks have a robust framework in which to calibrate the withdrawal of stimulus, they nevertheless have two challenges to finesse.

The first challenge is the supply-side nature of the inflation shock and uncertain effects of the pandemic on potential output (through, for example, its impact on labour supply decisions). Unlike a positive demand shock that raises output and employment and puts upward pressure on prices, supply chain disruptions have led to higher prices and, in some sectors, constrained output. In the former situation, monetary tightening contains inflationary pressures without necessarily departing from full employment objectives. But that may not be the case with respect to the latter shock, particularly if there has also been a loss of potential output owing to scarring effects. Over time, the nature of the shock and the implications of these effects will be better assessed; in the meantime, monetary policy decisions will likely be subject to increased uncertainty.

The second challenge is the effect that monetary policy rebalancing by the Federal Reserve and other advanced economy central banks could have on the region’s exchange rates. Sharp depreciations in domestic currencies stemming from a tightening of global monetary conditions and a shift in investor risk preferences could have harmful effects through two channels. The first channel is the pass-through effects on domestic inflation; as our team in Santiago observes in the country notes below, these effects are already showing up in higher inflation. The second channel is the impact on domestic balance sheets. With debt denominated in US dollars and revenues in domestic currency, large depreciations can lead to weaker balance sheets with negative implications for investment and growth.

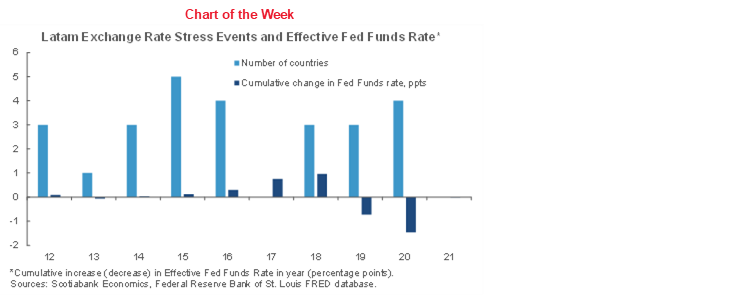

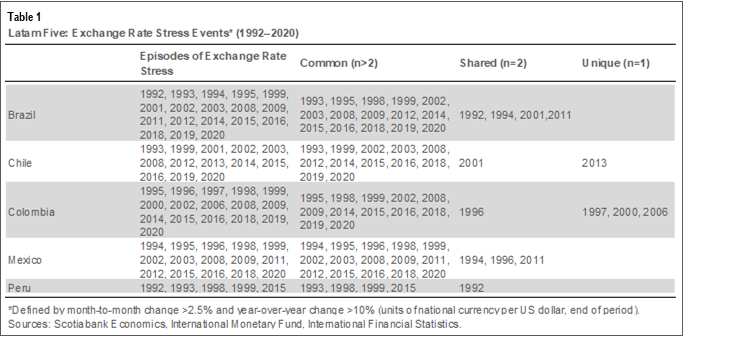

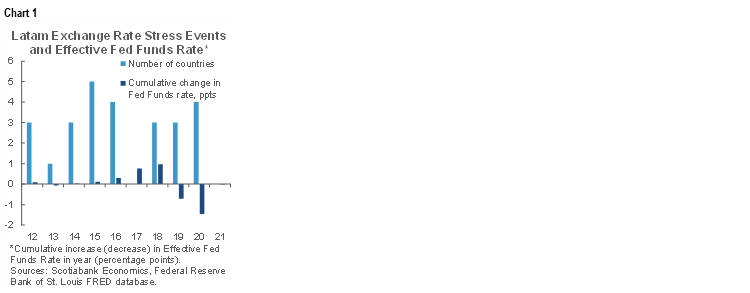

These effects account for a “fear of floating,” leading central banks intervene to moderate the pace of currency depreciation. Going forward, attention is thus likely to focus on possible currency fluctuations from the Fed’s rebalancing of monetary conditions. To assess the potential for such episodes, we have identified years in which the Latam Five countries have experienced periods of exchange market stress, as defined by two admittedly ad hoc criteria: large (>2.5%) month-to-month depreciations in the currency that coincide with significant (>10%) year-over-year changes (table 1). A quick look at the incidence of these events and the 2015-2018 Fed tightening cycle (chart 1) suggests, not surprisingly, that the stress events are more likely to be triggered by the start of a Fed tightening cycle as international portfolios are rebalanced.

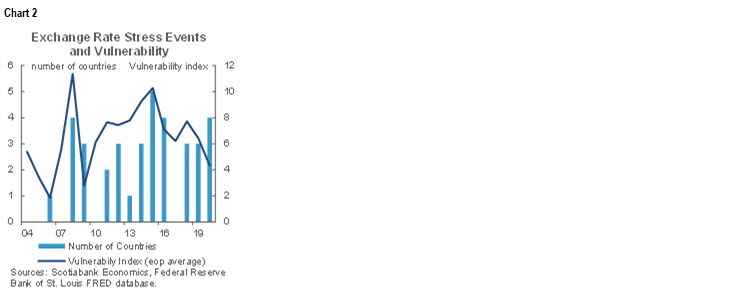

That conclusion says little about the region’s vulnerability to such episodes going forward, however. To address this question, a simple index made up of four indicators (inflation, external debt as a share of GDP, international reserves in months of imports, current account balances) was constructed, with higher values of the index representing increased vulnerabilities (chart 2). The index signals increased vulnerabilities around the global financial crisis and the Fed’s pre-pandemic tightening cycle, but not stress events associated with the COVID-19 pandemic given the unprecedented and unforeseeable economic and financial shocks associated with public health lockdowns. Moreover, while the index does not signal obvious region-wide vulnerabilities looking ahead (in part, perhaps, because of its rudimentary structure), some country-specific changes in underlying indicators are noteworthy. Inflation in Mexico, current account deficits in Chile, and external debt as a share of GDP in Colombia all warrant close monitoring. In this respect, while a Janus-faced look at exchange rate stress events does not necessarily predict exchange rate stress events that justify “fears of floating”, a prudent reading of past global financial tightening cycles does not support complacency in the face of potential risks.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Strong Economic Performance Despite High Political Uncertainty Prior to Runoff

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

56.2.2939.1495 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has continued to rise in recent days but at a slower pace. The positivity rate remained around 3% in the last week, and the vaccination campaign reached 91.2% of the eligible population. The occupancy of ICU beds and the COVID-19-related death rates increased but remain at low levels. Meanwhile, the rollout of booster (third) doses keeps moving forward, reaching almost 8.7 million people. Thanks to the success of the vaccination program, workplace mobility remains at pre-pandemic levels.

Positive market reaction after the election. On Sunday, November 21, right-wing conservative José Antonio Kast (Frente Social Cristiano coalition) and left-wing Gabriel Boric (Apruebo Dignidad Coalition) moved forward to the runoff vote to be held on December 19, as was largely expected. Mr. Kast secured the top spot with 27.9% of votes, while Mr. Boric won second place with 25.8%. Furthermore, right-wing coalitions increased their share in both houses, allowing a more balanced composition of the political forces in the Congress as of March 2022. After the results, equity markets rallied, interest rates fell, and the CLP showed a significant appreciation.

Looking ahead, we anticipate a tight December 19 runoff, in which the votes obtained by Mr. Franco Parisi (third largest share) will be the prize. In recent days, both presidential candidates campaigning for the runoff have been adjusting their economic programs to include some of the ideas of their political allies.

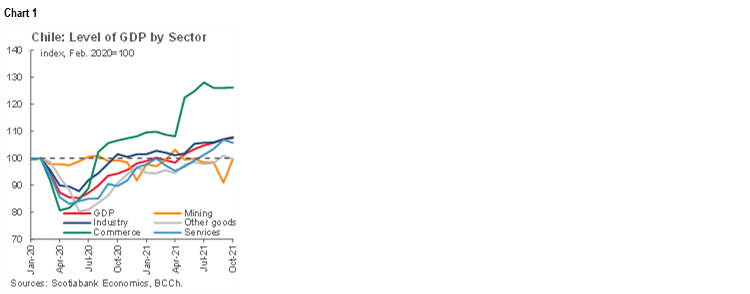

With regard to the economic indicators, on Wednesday, December 1, the central bank (BCCh) released the October economic activity index (IMACEC), which increased at a robust pace of 15% y/y (+0.8% m/m) despite high levels of political uncertainty. On a seasonally adjusted basis, the index shows a slowdown in services (-1.0% m/m) after a strong expansion in September (chart 1). Overall, the IMACEC posted a healthy-looking result and is not currently signaling an imminent slowdown alert. We believe that GDP should continue to show a favourable momentum in the first half of 2022 with either Gabriel Boric or José Antonio Kast as President.

As well, on Tuesday, November 30, statistical agency INE released the unemployment rate for the quarter that ended in October, which fell to 8.1%, thanks to an increase in employment (1.3% m/m). With this result, the employment gap compared to the pre-pandemic level fell to 607k, of which 338k corresponds to formal jobs and 269k to informal jobs.

Finally, CPI increased 0.5% m/m in November (6.7% y/y), in line with our expectations, largely reflecting the depreciation of the Chilean peso and related pass-through effects (chart 2). The CPI excluding volatile products was 0.7% m/m, while the CPI core was 0.5% m/m (5.8% y/y), largely explained by increases in prices of goods (1.5% m/m; 7.5% y/y). Services took a break this month, with a fall of 0.1% m/m (4.8% y/y), but it is expected that they will continue to push inflation upward in the coming months. All in all, inflation remains above recent historical highs and the exchange rate has continued to depreciate, fueling additional pressures on costs (chart 2). We expect the central bank to hike the MPR by 125 basis points (bps), though it is likely considering a range of between 100 bps and 150 bps.

Last week, Congress finally rejected the bill for a fourth withdrawal of pension funds. Furthermore, on Monday, November 22, the lower house passed the 2022 Budget Bill presented by the government in September. Overall, the approved Budget Bill maintained the level of spending proposed by the government (USD 82 bn), which implies an increase of 3.7% y/y in real terms compared to a 2021 base-year without the additional fiscal support measures. In our view, the approval of this Budget Bill represents a positive signal for fiscal sustainability, as it will imply a reduction in the structural deficit. Over the next few years, new authorities will decide about the fiscal commitment.

In the fortnight ahead, on Tuesday, December 14, the BCCh will have its last monetary policy meeting of this year. As mentioned above, we expect a rise in the MPR of 125 bps, towards 4%. On Wednesday, December 15, the BCCh will release its Monetary Policy Report for Q4-2021, which will likely feature a slight upward revision in 2021 GDP growth, approaching 12% (from a previous range between 10.5% and 11.5%). Lastly, on Sunday, December 19, the runoff of the presidential election will be held.

Colombia—Key Facts Ahead of the Elections in 2022

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Markets are looking closely at the political risks in the Latam region owing to a crowded electoral agenda, among other political events. Colombia, for example, will hold congressional and presidential elections in the H1-2022. The elections are especially important since the next government must send major reforms to Congress to ensure long-run fiscal sustainability after the sharp deterioration in fiscal accounts attributable to the extraordinary policy response to the pandemic.

The response to the pandemic led to a significant increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio from 46.6% in 2019 to roughly 60% of GDP in H1-2021 and the fiscal deficit now hovers around 8% of GDP, with a deficit of 7% expected in 2022. In 2021, the government passed a fiscal reform that would increase fiscal income by 1.2% of GDP. However, that increase represents only 2/3 of what is needed, and the next government should complete the task. Therefore, it is important to analyze what are the chances of the next administration to pass tax, pension, and labour reforms. We think it will depend critically on the skills of the next president to negotiate with a Congress in which the composition would be very split since any party could have a majority.

That said, ahead of 2022 elections it is relevant to identify some key facts:

- First, it is important to keep in mind that political power in Colombia is divided among the Courts, Congress, and the president. Therefore, although the name and affiliation of the president are relevant, to pass difficult reforms, legislation must be negotiated with Congress and ratified by the Constitutional Court. That structure tends to entrench the political and economic status quo.

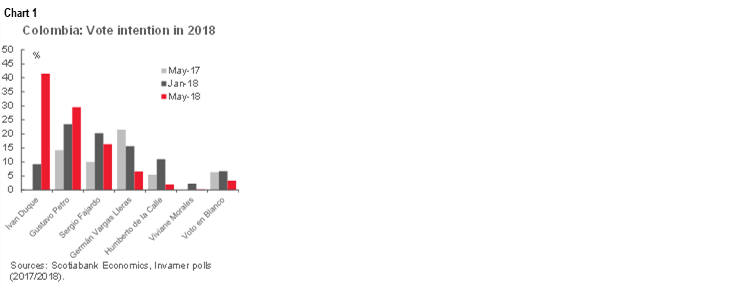

- Second, in Colombia the most intense phase of presidential campaigns starts in mid-January of the election year. In fact, according to the main polls, with only four months before the first round four years ago, the candidate Duque (today’s president) had only 9% of voter intentions by January 2018, while four candidates, Gustavo Petro (22%), Sergio Fajardo (19%), German Vargas Lleras (15%) and Humberto de la Calle (11%) had higher shares of voter intentions (chart 1). Moreover, on average, Colombian voters decide their vote one month before the election and around 10% of voters decide one week before. Therefore, we will not have a better idea of which candidates have a real chance of winning the presidency until February or March 2022.

- Third, there is an atypically high number of pre-candidates (at least 50) running, so that alliances forged during the campaign are going to be key to winning the presidency. Currently, nobody running has the votes to win in the first round, so coalitions will be critical to winning in the second round. For now, there are three potential alliances, Coalición Centro Esperanza, considered centre-left and led by Sergio Fajardo which was third in the 2018 elections; Equipo for Colombia, considered centre-right and led by former Minister of Finance Juan Carlos Echeverry; and Pacto Histórico considered left and led by Gustavo Petro. Those alliances will define the candidates in Congressional elections in March; and after that the battle of the campaign will start.

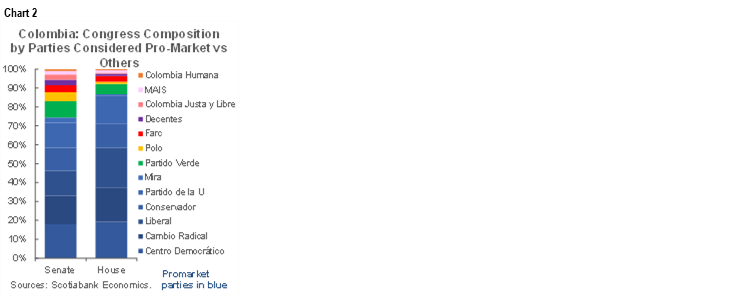

- Fourth, historically Colombia has had a very diverse Congress, although pro-status quo parties form the majority (chart 2). Although we expect some small changes to the composition of Congress after the March elections, we anticipate that pro-status quo parties will continue to make up something more than 75% of Congress. Therefore, the next president must have the skills needed to negotiate with many minorities in order to be able to pass significant reforms.

Looking ahead to the new year, all of the above make us think that it is too early to draw any conclusions about which candidate can or cannot win next year’s elections. Additionally, we also believe that no candidate will have the majority or public favour needed to change the status quo given the strong institutional framework that the 1991 Constitution established. Nonetheless, we do anticipate higher volatility in the local markets during Q1-2022 and caution with respect to investment decisions in the real sector, reflecting the regional geopolitical environment, uncertainty regarding the Colombian presidential elections, and the possibility of changes to the economic status quo, however slight those prospects might be.

Mexico—Forecast Revisions: Year-end Brings Bad News for Growth and Inflation

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

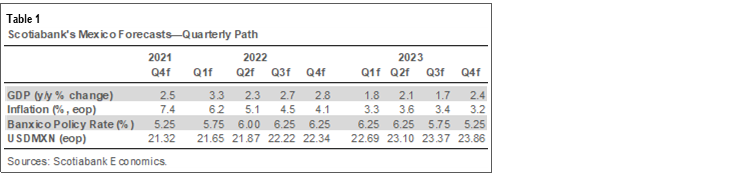

As we have signaled for the past few weeks, we made several revisions to our Mexico forecasts (table 1). The most material are changes to 2021 growth (lower) and inflation (higher), but we also changed our 2022–2024 projections, including for Banxico’s terminal rate. On the growth front, the second half of the year has seen a shift in Mexico’s major growth drivers, going from an externally driven recovery (a record trade surplus in H2-2020 of over USD 5 bn/month on average, and still-record levels of remittances, which should top USD 50 bn in 2021) to a domestic demand rebound (the trade balance has swung into a USD 3 bn/month deficit in H2-2021, and consumption and consumer confidence have improved). We are also seeing a gradual recovery in lagging sectors, especially in services, although the recovery in tourism and entertainment is still nascent (or slow). Investment has remained a key underperforming sector, and dropped from an average of over 23% of GDP in the decade leading into 2018, to a low of 19% in the pandemic. We anticipate investment will pick up somewhat to just over 21% of GDP over the forecast horizon, but it remains a weak spot in Mexico’s long-term growth drivers.

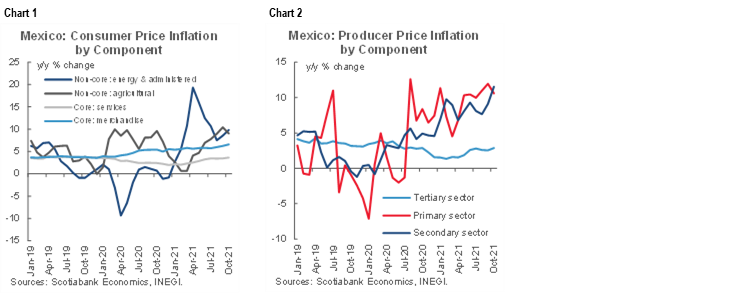

On the inflation front, core inflation continues to rise, despite being anchored by low inflation on both housing and education (both hovering close to 2%). So far, the main drivers of inflation have come from goods, where activity recovered faster, and a demand re-composition towards goods from services (chart 1). However, we anticipate that going into the close of 2021, and into the first half of 2022, services price inflation will push headline and core higher. Also adding to price pressures have been supply-side disruptions, commodity prices, and producer prices for firms in the primary and secondary sectors, which have been high and rising for the past year and a half (chart 2).

On Banxico, we don’t anticipate the acceleration in the pace of Banxico’s rate hikes in next week’s meeting (an increase from 25 bps to 50 bps), which markets have largely priced-in (60-80%) in recent days. There are several reasons for this:

- First, we don’t believe that Mexico needs to maintain a pace of 50 bps hikes given that monetary conditions never got anywhere as loose as other regional economies during the pandemic. In our view, a gradual move towards neutral-to-slightly-tight conditions should be enough to anchor inflation, especially as we head into mid-2022, when we expect statistical and calendar effects alongside a gradual solution to supply-side disruptions leading to an easing of price pressures. Our estimates suggest that a gradual move of the policy rate towards 6.0–6.5% over the coming 12 months will be enough to bring policy settings to neutral/slightly tight. This recalibration should both provide a buffer for domestic markets as the Fed’s own rate hike cycle kicks in, and at the same time help curb inflationary pressures. On this front, we made a modest revision to expected hikes, increasing our terminal rate estimate by 25 bps.

- Second, with markets expecting future Governor Veronica Rodriguez to be more dovish than current Governor Diaz de Leon, we think the current Board would be reluctant to undermine do her credibility by hiking 50 bps, only to then have the new Board reduce the pace of hikes.

- Third, there is very little to go by in interpreting the designated future governor’s monetary policy views, other than her confirmation presentation to the Senate. However, from recent conversations we’ve had, Rodriguez is seen as a mentee of former Finance Ministers Arturo Herrera and Carlos Ursua, as well as Deputy Governor Esquivel. She studied under two of the three individuals and worked closely with all three in different government roles. Given her closeness to Esquivel, we would not be surprised if some of their views on monetary policy align, which we think makes it difficult for the pace of hikes to move to 50 bps under her mandate.

- Fourth, feedback we’ve received on future Governor Rodriguez describes her as having a strong/independent personality, being a hard worker and fast learner, all of which bodes well for her capacity to adapt to her new career as a central banker. The feedback we’ve received also supports her focus on supporting Banxico’s independence in her ratification hearings in the Senate.

Peru—Peru’s Schizophrenic Economy

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

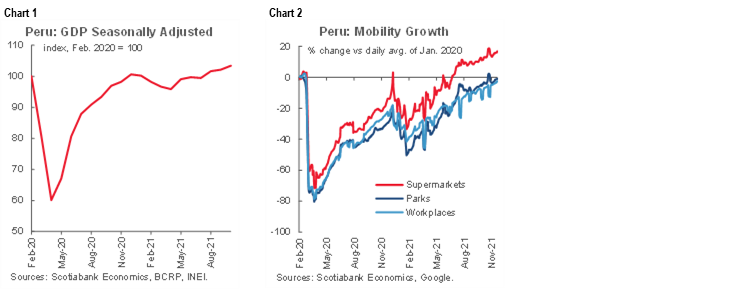

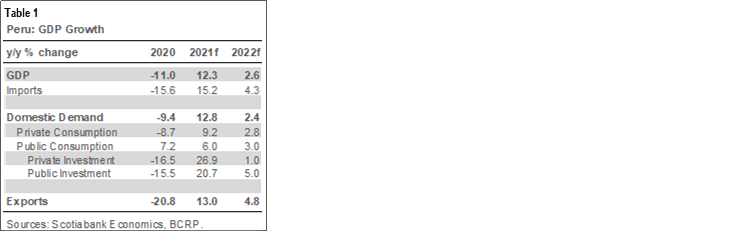

It’s been an exhausting 2021. It’s been a year in which it seemed that Peru could not catch a break in its political turbulence. And yet, it would be hard to tell from just looking at the economic data that anything was really amiss. GDP growth, both the aggregate and domestic demand components, have surprised on the upside to such an extent that we see upside to our already robust 12.3% GDP forecast for 2021 (chart 1). There seems to be little evidence in high-frequency data—such as traffic, electricity demand, and cement demand—that the change in government, as bumpy as the ride has been politically, has affected growth trends. All high-frequency indicators and most mobility indicators are mildly above 2019 levels (chart 2). So is GDP, up 0.5% in the year-to-September, versus 2019. Most analysts were not expecting a return to 2019 levels until well into 2022 (table 1).

Macro balances are also bearing up very well. High metal prices have helped raise the trade surplus to a record USD 9.6 bn in the year-to-September. Our forecast of USD 13.8 bn for the full-year 2021 is the highest ever recorded, and 67% above 2020, which was also a very strong year. To add to the bright picture, the fiscal deficit is plunging. The year opened with a fiscal deficit at 8.9% of GDP. This has fallen to 4.1% of GDP to October and should continue declining towards our forecast of 3.5% of GDP in 2022. All this is enough to put a smile on your face.

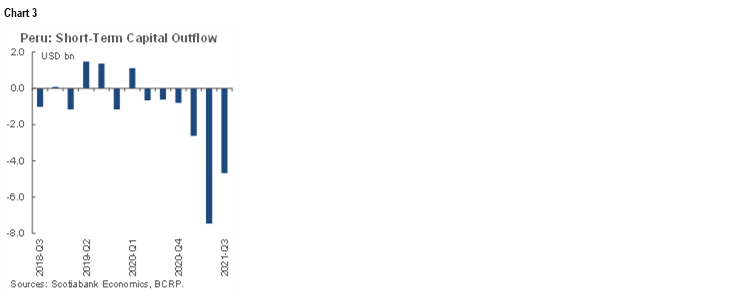

But then you look at the financial markets and price volatility, and you get the flip side of the coin. Yes, the trade surplus in the first three quarters of 2021 was a record. But, the outflow of short-term capital was even greater, at USD 14.6 bn in the year-to-September (chart 3). This was not only a record outflow, but it was orders of magnitude greater than any previous year. Furthermore, most of the outflow came from domestic investors and households, as opposed to offshore accounts, which means that domestic resources were fleeing the country, rather than foreign resources returning home. A very nervous local population has flocked to the dollar, caused the USDPEN rate to rise 22% during the year, and pushing the BCRP to try to arrest the buying panic by supplying the market with a record USD 16.6 bn in USD currency and USD derivatives.

Inflation has also emerged as a concern to a degree not seen for a very long time in Peru. It’s tempting to place the blame entirely on global contagion, but the weakened PEN—during a period in which the PEN should have been strengthening—also contributed. We expect inflation to remain above the BCRP’s 3% target range ceiling for some time. Our inflation forecasts are 6.5% for 2021 and 4.5% for 2022 and, if anything, we may be underestimating inflation for 2022. For inflation to subside will depend on both Peru’s political front settling down, and global prices starting to stabilize. Until it does, the BCRP will be under pressure to continue raising its reference rate.

So, what does all this mean going forward? The balance of Peru’s economic split personality is that, instead of growing +5% on average over the next few years, as it could under the present circumstances of sturdy macro balances, high metal prices and strong short-term rebound, we continue to expect 2.6% GDP growth in 2022, and in the mid 2% to 3% range henceforth. Meanwhile, the BCRP will need to continue to be active in seeking price stability without hampering growth.

We expect political uncertainty and erratic policy judgements to persist, even as the economic agenda is much more orthodox and less erratic. Stable economic policy helps. But this appears to be an island in an overall environment in which other policymaking is erratic and the government leadership lacks statesmanlike qualities. This makes for an outlook fraught with uncertainty, with special risks for high-profile sectors such as mining. Government management concerning social conflicts is affecting mining in a very real way, with mines representing 38% of copper production, and over 7% of gold and silver output, having had to close for varying periods of time. However, it is not only mining that is at risk, as management decisions affecting sectors as basic as transportation, energy, education and agriculture are also a concern.

As elsewhere, a new COVID-19 wave also poses a potential risk. COVID-19 had languished to its lowest levels since the pandemic began in early 2020. However, there has been an uptick lately, which is still too weak for the government to consider new mobility restrictions, but this may change.

Another concern is that employment is lagging GDP. The future of jobs growth depends crucially on investment in expansion projects, which do not appear to be forthcoming to the degree needed. Both private and public investment performed robustly in 2021, but private investment took place not in the more labour-intensive expansion projects so much as in technology (especially greater digitalization), which is rather labour-saving, and in new start-ups of small, individualized, businesses that have benefitted from the sharp shift in household preferences towards home delivery, and on-line sales and payments formats.

Perhaps the greatest risk for the country going forward is poor state management, which, in the end, could lead to a progressive deterioration in state institutions. At the same time, if the government were to move towards greater moderation, stability, and policy coherence, it would not take all that much for the economy to accelerate.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.