FORECAST UPDATES

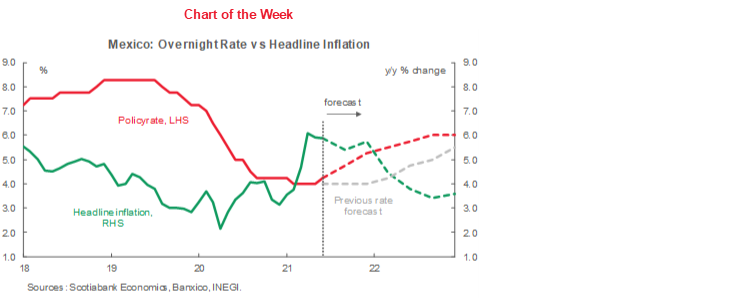

- Banxico’s proactive move to prevent a temporary spike in inflation spilling over into longer-term expectations prompts us to revise our call on policy rates.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- Surprise policy rate hikes in Mexico and Chile highlight the policy challenges facing monetary policy.

- But fiscal policy challenges also loom large, as governments balance higher pandemic-related debt burdens against the continued need to assist vulnerable individuals and support nascent recoveries.

- Fiscal anchors and clear policy direction can help maintain investor confidence and assuage debt sustainability concerns.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period July 17–30 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: Fiscal Policy Challenges After the Pandemic

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Latam central banks are grappling with rising inflation and the need to get the timing right on unwinding extraordinarily accommodative monetary conditions. Moving too soon, too aggressively could imperil recovery. Waiting too long risks embedding temporary inflation into expectations.

- Surprise policy rate hikes in Mexico and Chile highlight this dilemma.

- There are also important fiscal policy challenges coming out of the pandemic, notably the need to balance support for vulnerable groups most affected by the pandemic and sustaining the investor confidence needed to preserve or expand fiscal space.

- Fiscal rules can help strike a felicitous balance. And while most Latam countries have some form of fiscal anchor, these rules can be strengthened. The sooner this strengthening happens, the better.

FISCAL POLICY AFTER THE PANDEMIC

The COVID-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented shock, one that triggered steep declines in economic activity across a broad range of countries. Latin America was not immune, as the region bore a disproportionate burden in terms of case counts and, tragically, the number of deaths. Moreover, as it has elsewhere, the pandemic has widened inequality and pushed millions into precarious economic situations. And while the human costs of the pandemic are impossible to tabulate, a recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) working paper reckons that the economic downturn triggered by the pandemic is the region’s most severe recession in over a century.*

Latam governments responded to public health and economic challenges with a range of measures to support vulnerable populations. These actions were taken despite a trifecta of limited fiscal space, falling output, and shrinking revenues; the counter-cyclical fiscal responses are shown in charts 1–6. As the charts illustrate, most governments in the region increased expenditures early in the pandemic even as real GDP was falling. Mexico is an exception: the government there responded to the pandemic by curtailing expenditures. Elsewhere, governments ramped up spending to ameliorate the effects of lockdowns on incomes and bolster public health resources.

Such efforts are easily justified. COVID-19 introduced an enormous temporary shock to incomes, in response to which borrowing to smooth consumption is entirely appropriate. But many individuals, lacking the resources from which to provide collateral or working in the informal sector, were locked out of borrowing markets. In such circumstances, fiscal assistance in the form of direct transfers financed by debt represented, in effect, government borrowing on behalf of credit constrained households. Similarly, buttressing public health care systems is clearly warranted in the midst of a global pandemic.

Yet, however justified by the exigent circumstances of the pandemic, these fiscal responses have increased public debt burdens across the region. And where fiscal responses were more muted, as in Mexico (see discussion below), falling revenues led to a deterioration in fiscal balances. Table 1 shows the marked increase in general government net debt, calculated as gross debt less the value of financial assets, as a share of GDP. As the IMF projections in the table illustrate, the net debt as a share of GDP of most countries is expected to gradually increase over the medium term. Here, again, Mexico, whose net debt is projected to remain broadly stable, is the exception.

Higher debt burdens do not necessarily pose a significant risk to sustainability in the current “lower for longer” interest rate environment. With global interest rates at historically low levels, debt-servicing costs are expected to remain stable or increase only modestly even with higher debt burdens. And with inflation running above nominal interest rates, real interest payments are expected to remain flat or decline slightly over the medium term.

But continued low interest rates cannot be taken for granted. Enormous uncertainty hangs over the outlook, with bond markets reassessing the reflation trade as US inflation has increased. The key question is whether higher inflation is a transitory phenomenon, fuelled by supply bottlenecks and base effects, or could, more worryingly, become embedded in expectations.

Meanwhile, last month’s slightly hawkish dot plot chart of Fed governors’ interest rate expectations has put Latam central bankers on notice—their challenge is to watch the plots and mind the (output) gaps as their economies recover. On June 24th, Mexico’s Banxico surprised markets with a policy rate hike that our team in Mexico City views as the start of front-loaded tightening cycle designed to anchor inflation expectations (see the July 9 Latam Flash). Likewise, in Chile, the central bank (BCCh) raised its key policy rate 25 basis points on July 14th despite June inflation surprising on the downside, in what our analysts in Santiago view as an early start to the renormalization process (see the July 14 Latam Daily). And while other regional central banks have thus far remained on the sidelines (see discussions of Colombia’s BanRep and Peru’s BCRP below), the moves by Banxico and BCCh underscore the uncertainty surrounding the future path of interest rates and the risks that higher rates could pose to fiscal balances.

At the same time, the pandemic has reanimated demands for policies to ameliorate social issues, such as growing inequality and poor public services. In Colombia, for example, these concerns led to nationwide protests earlier in the year that disrupted production in some sectors. Addressing pressing social issues would put additional stains on fiscal resources across the region. These concerns also likely underlie the election of Pedro Castillo in Peru.

Fiscal policy must therefore balance the need to tackle these issues while maintaining market access on favourable terms. The challenge is complicated by the fact that too aggressive retrenchment of the extraordinary support policies that have supported individuals and firms through the pandemic could jeopardize nascent recoveries, which remain fragile, and could undermine efforts to resolve longer term economic and social issues. Sustaining market confidence may be the key to achieving this balance. This assessment reflects the simple observation that a government’s fiscal space—the amount of debt it can comfortably issue and rollover—is endogenous, depending in part on financial markets’ expectation of future fiscal policy actions: If investors anticipate that a government is likely to issue a surfeit of debt in future periods, thereby diluting their claims on the revenues needed to service existing debts, they will limit their lending in the current period.

Fiscal rules that constrain future policy are one way to assuage such concerns and increase fiscal space. Latam governments have implemented a range of measures to anchor expectations and sustain market confidence. Table 2 provides a “heat map” of fiscal anchors reflecting the basis of key fiscal rules. It reveals considerable dispersion across the region. Mexico has the most comprehensive set of fiscal rules covering the budget balance, debt levels and debt reduction targets, as well as expenditures and revenues. Moreover, these rules have a legal basis, which may give them greater credibility than, say, a fiscal anchor that reflects a political commitment, which may prove less secure when stressed. Argentina, in contrast, has only a political commitment with respect to the primary budget balance. Other Latam countries are distributed between these two poles with fiscal rule regimes of varying scope and institutional foundations.

Because fiscal rules that trigger incredible policy responses in the face of large exogenous shocks are unlikely to lend credibility, most rules-based frameworks provide for an “escape clause” that suspends rules in such circumstances. Countries in the region exercised this option early in the pandemic without suffering serious market repercussions, possibly suggesting that their fiscal rule regimes are viewed as credible. Their experience is also consistent with other empirical evidence—albeit limited—presented in the IMF study cited above that spreads of countries with fiscal rules widened by less than those of countries without a fiscal rule.

Most fiscal frameworks, however, offer limited guidance on how countries will return to their targets and how deviations from the rule will be made up. For example, Peru’s fiscal rule was suspended (in principle, only through 2020–2021), although this may be extended. That said, in the interim, the fiscal targets to be used in designing the budget, debt management and for the fiscal balance framework are provided by the Marco Macroeconómico Multiannual, MMM (Multi-year Macroeconomic Framework, prepared by the Ministry of Finance). The current MMM 2021–2024 provides a 2021 fiscal deficit target of 6.2% of GDP and a debt-to-GDP ratio of 38.0%, which our team in Lima believes should be easily attainable. Over the medium-term, the MMM calls for a reduction of the fiscal deficit to 1.0% of GDP by 2026.

More fundamentally, as the heat map in table 2 shows, there is room to strengthen fiscal anchors in most Latam countries. Doing so could help finesse the daunting fiscal challenges that lie ahead. In this context, in the wake of a recent downgrade, Colombia’s government on July 14th unveiled plans to change the fiscal rule from a deficit rule to a simple, transparent debt-to-GDP anchor on gross debt, in conjunction with fiscal reforms to raise revenues and extend direct monetary transfers to vulnerable households (ingreso solidario) until 2022, increasing their coverage (see the July 14 Latam Daily).The debt target is set at 70% over the next two years, falling afterwards to 55% over the longer-term. Other social measures announced include zero fees at public universities and subsidies through to 2022 for companies that hire young workers. These programs aim to reduce social tensions ahead of a busy electoral calendar between now and 2022. And our team in Bogotá believes the reform package will garner the support of a wide range of stakeholders, including key economic groups, youth leaders, and congressional representatives, increasing the likelihood of it passing before the end of August.

* Fiscal Policy Challenges for Latin America During the Next Stages of the Pandemic: The Need for a Fiscal Pact by Mauricio Cardenas, Luca Antonio Rocco, Jorge Roldos, and Alejandro Werner. IMF Working Paper WP/21//77, March 2021.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

CHILE—ADJUSTMENTS TO “PASO A PASO” PLAN. THE RECOVERY CONTINUES. CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE GETS UNDERWAY.

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Following a decrease in new cases and hospitalizations related to COVID-19 (chart 1), on July 8th Chilean authorities announced adjustments to the “Paso a Paso” plan reducing mobility restrictions for fully vaccinated individuals. Capacity restrictions on certain activities were also updated, providing increased flexibility in the operation of restaurants, gyms and cinemas and reducing curfew hours, depending on the level of infections and vaccination by region.

Meanwhile, the economic recovery continues. Retail Sales remained high in June, but we observed some deceleration in July, driven by Supermarkets and Department Stores as well as the effects of seasonal patterns (CyberDay). Our high-frequency indicators point to a slowdown in purchases with credit and debit cards at the beginning of July (chart 2), suggesting that the high liquidity coming from fiscal aid and the withdrawal of pension funds is being consumed, though a significant proportion is likely being saved.

On July 12th, the Ministry of Finance released its quarterly report of Public Finance for Q2-2021 updating the government’s financing needs for this year to reflect the new measures to support households and firms and revising its forecast of 2021 GDP growth to 7.5% (from an earlier 6.0%). Financing requirements for 2021 are estimated around US$ 36.2 billion, of which US$ 17.5 billion remains to be financed in the second half of the year, US$ 15.1 billion of which will be financed by issuing public debt and the remainder through USD asset liquidation. Of the US$ 15.1 billion of public debt issuances, US$ 8 billion will be announced soon and will be issued mainly in foreign currency. The Ministry of Finance further estimates an effective fiscal deficit of 7.1% of GDP for 2021 and a debt level of 38.5% of GDP for 2025, lower than previous estimate of 39.5% of GDP.

In June, the Consumer Price Index increased 0.1% m/m (3.8% y/y), in line with our expectations, and below consensus (0.3% m/m) and forward contracts (0.34% m/m). The increase was driven mainly by higher fuel prices, while core inflation was lower than consensus, which supports our view that inflationary pressures will abate in the second half of the year.

On July 14, the Central Bank of Chile (BCCh) held its monthly monetary policy meeting, deciding to increase the benchmark rate up to 0.75%. The BCCh reported GDP growth driven by consumption and higher trade volumes. The BCCh slightly moderated its prospects for the world economy, recognizing the risk arising from the spread of new variants of Covid-19, as well as a significant lag in the advancement of the vaccination process in many emerging economies. The Central Bank statement does not indicate a trajectory of aggressive increases in the Monetary Policy Rate. We project that the next hike of 25 basis points will occur in Q4-2021.

In the fortnight ahead, on July 30, the BCCh will release the July Monetary Policy Meeting Minutes, which will provide more details on the Board’s discussion regarding the decision of increase the policy rate in 25 basis points. We maintain our view that the Monetary Policy Rate will not exceed 1% in 2021, with subsequent increases to a terminal rate of 1.75% in December 2022.

Moreover, on July 30, the INE will publish industrial production and retail sales data for June along with the unemployment rate for the quarter that ended in June, which we expect will remain around 10%.

In the political arena, the inaugural session of the Constitutional Convention that was elected in May was held Sunday, July 4th. Elisa Loncón (age 58), a political independent and indigenous representative of the Mapuche people, was elected as president of the constitutional body, obtaining 62% of votes in a two-round vote. Voting strategies of the various political coalitions revealed, however, that no political group is likely to secure the minimum (104 members) two-thirds majority required to approve each article in the new constitution. In this respect, the session was the first indication of how the various coalition forces within the diverse and fragmented convention will work. Negotiations and concessions will be needed from both the left- and right-wing coalitions to reach that benchmark.

COLOMBIA—THE BANREP'S ORTHODOXY IN UNCERTAIN TIMES

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

The central bank of Colombia (BanRep) is widely regarded as one of the most independent and orthodox central banks in the Latam region. In fact, Banrep´s monetary policy reaction function has long put more weight on inflation gaps (and inflation expectations) than the output gap (chart). And while Banrep has many ways to intervene in the FX market, recent history has shown that it prefers to let the currency float. For example, last year the Board decided to increase international reserves on two occasions (May 8, 2020 and Dec 3, 2020) even though the COP had depreciated by more than 10% in less than a month. In this respect, BanRep has long been viewed as a conventional inflation targeting central bank; one that thinks in the long run and keeps inflation expectation firmly anchored, allowing the floating exchange rate to serve as the first shield against international shocks.

PANDEMIC-INDUCED UNCERTAINTY

We do not think BanRep has changed its basic approach. However, the depth of the recession triggered by the pandemic may have led it to reconsider how far potential output fell and, therefore, how big a negative output gap was opened. This calculation is particularly challenging because we do not yet know how much of the COVID-19 shock is permanent and how much is temporary. In contrast, current inflation and inflation expectations are available (albeit with a lag) on a timely basis.

The upshot of this asymmetry in information sets is that the conventional reaction function, which weighs inflation and inflation expectations over the GDP gap, may be less effective guide to possible policy actions. Uncertainty around how big the real shock has hit economic activity could make the board increase (at least temporary) the importance of the output gap in its reaction function.

ASSESSING THE CURRENT CONJUNCTURE

In the current situation, with inflation and inflation expectations in the upper half of the target range and economic activity showing unexpected resiliency, pointing to growth above 6% in 2021, the traditional reaction function would likely dictate that the hiking cycle should have started in June 2021 to get a neutral rate of (4.5%–4.75%) by 2023.

In our opinion, however, uncertainty may have led the Board and staff to give the output gap more weight until additional information on economic activity and the pace of the recovery is received. In effect, they may delay policy rate normalization until model updates and new data confirm that the recovery has consolidated, and that the output gap is indeed narrowing.

MODEL UPDATES, DATA, AND VIRTUE OF PATIENCE

Ahead of forthcoming monetary policy meetings, it is thus worth noting that BanRep´s staff updates its macro forecast every quarter. In July, the staff will have new model results but data for 2Q21, will still be outstanding, which probably reduces confidence in starting a hiking cycle. In October, however, BanRep will rerun its models with more information; the results of that exercise could auger a more hawkish tone. In the interim, BanRep´s board has signaled that it is content to wait for more data, provided inflation expectations remained firmly anchored.

In this respect, while BanRep staff revised up their inflation and GDP projections in the most recent forecast round, the economy has demonstrated considerable resilience and growth and inflation will likely continue to run above BanRep expectations. Meanwhile, the COP has depreciated after the last monetary policy meeting, and the downgrade of Colombia’s rating put some additional pressure on the FX that can affect inflation expectations.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY RATES

Putting all this together, in our view, BanRep has two options. First, keep the policy rate at 1.75% in the July meeting but send a hawkish message, which a divided vote would convey, and reveal more hawkish model results to signal a likely hike in September. Second, wait until October to have more information on the economic activity recovery and start the hiking cycle then.

Although it is a close call, we are keeping our forecast that September will be the kickoff of the hiking cycle in Colombia. Either way, the July 30th monetary policy meeting will be key to assessing future moves since we will have a fresh forecast from BanRep and the opportunity to parse the tone of the Board’s communications.

MEXICO—FISCAL RESTRAINT IN THE PANDEMIC, REDUCED FISCAL PRESSURES IN THE RECOVERY. BUT COULD RESTRAINT ENTAIL LONG-TERM COSTS?

Miguel Saldaña, Especialista de Análisis Macroeconómico

+52.55.5123.0000 Ext. 36760 (Mexico)

msaldanab@scotiabank.com.mx

Paulina Villanueva, Especialista Investigación Económica Especial

+52.55.5123.6450 (Mexico)

pvillanuevac@scotiabank.com.mx

Mexico maintained an austere fiscal position during the pandemic, limiting the increase in additional spending to 0.7% of GDP, and practiced prudent debt management. Despite this restraint, debt nevertheless increased from 45.1% of GDP in 2019 to 52.1% of GDP in 2020. Most of this increase can be attributed to the depreciation of the MXN, which raised the domestic currency value of foreign currency-denominated debts, and the decline in economic activity, which adversely affected revenues. But because both effects have likely been largely absorbed, the Ministry of Finance estimates that debt will decrease from 52.1% to 51.0% of GDP in 2021. This means that, unlike many other countries, Mexico does not face the same pressure to scale back government support and face the political and economic risks that reversal could entail.

The government's austere fiscal stance entails important trade-offs, however. While it enhanced credit valuations by limiting the increase in government expenditures and debt, in the context of the pandemic, it may have negative implications for the long-term performance of the economy. The policy response to the coronavirus shock provided limited liquidity and income support to businesses and households and therefore did little to counter the economic impact of the shock. In the absence of a more robust response by the government, income and employment levels deteriorated and many small businesses faced bankruptcy, hindering the economy's ability to recover at a faster pace. Even after removing the coronavirus-induced contraction in GDP, we expect medium-term growth to average around or below 2% after 2021 as a result of negative business sentiment and persistently weak investment. This rate is lower than the 2.7% average in 2010–19.

Against this backdrop, the new Secretary of Finance, Rogelio Ramirez de la O (who will be succeeding Arturo Herrera so Herrera can head the Banxico) will therefore have a daunting challenge to keep debt levels under control while fostering economic growth beyond 2021. We believe his most ambitious project will be to implement a long-awaited tax reform next year, which will likely be proposed in September when the next congressional session begins.

As for Mexico’s Central Bank, Banxico, as discussed in last week’s Global Economics report we are expecting a further 100 bps of tightening coming in 2021 to close the year at 5.25% compared to our earlier 4.00% forecast for end-2021. Although we have adjusted our forecasts to reflect a much more aggressive and earlier tightening cycle from Banxico than we previously thought, there are risks that the Board could raise rates by a bit less or a bit more. In our view, however, the dominant risks are to the upside—with the possibility of an even more hawkish path than the new forecasts we’ve laid out. We have also adjusted our longer-term profile for monetary policy in Mexico to a 6.00% terminal rate by Q3-2022—essentially the neutral real policy rate based on our inflation forecasts—up from 5.50% in Q4-2022 in our previous forecast.

PERU—WAITING FOR A NEW GOVERNMENT

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Mario Guerrero, Deputy Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6000 Ext. 16557 (Peru)

mario.guerrero@scotiabank.com.pe

As in Samuel Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot, in post-election Peru one might say: “Nothing happens. Nobody comes, nobody goes. It's awful.” Never before has it taken so long for the authorities to announce the winner of an election. The announcement should, however, come in a matter of days if only because time is running out. The inauguration date for the new government is July 28, leaving precious little time for a proper transition process. In this uncertain environment, markets are generally coming around to the idea that Castillo will ultimately be declared the winner. Perhaps. But until the new President is officially proclaimed, we will not know what the next cabinet will look like, or the profile of the new government.

The next three of four weeks will be crucial for the outlook of Peru’s economy and social-political environment. Over this period, we will learn not only who is in the cabinet, but also whether Julio Velarde will remain at the helm of the central bank (BCRP). We will hear the incoming president outline the new government’s vision and policies in the July 28 inauguration speech. We will also learn who will be chosen to preside over Congress and get a feel for what to expect of it. And later in August, the cabinet will present its policy proposals to Congress, which will give us insight into what type of relationship the two institutions are likely to forge. Finally, towards late August or early September, the government must submit its 2022 fiscal budget to Congress.

This packed schedule should clarify the future government’s policies, priorities, and management capabilities. But we should also get a better idea of a timeline and procedures for a possible change in the Constitution. In a word, after weeks—if not months—of uncertainty, Peru is entering a phase of definition… for better or for worse.

The good news is that the new government will inherit a fairly encouraging situation. Most important, good progress has been made in getting COVID-19 under control. Hospitalizations are at 50% of their peak levels, and fatalities are at their lowest level since 2020. Nearly a third of the population has had at least their first vaccination. Mobility indicators have returned to their highest levels since the outbreak,.

The economy is also recovering nicely. We expect growth in Q2-2021 to be at least 34% y/y. This remains about 3% lower than 2019 pre-COVID levels but is quite robust considering that mobility restrictions were still in place during this period. Indicators that have surpassed pre-COVID levels include electricity demand and cement demand, with mobility indicators also improving. Once the government defines its governing team and policies, we will have another look at our forecasts, but, for now, and based purely on trend, there seems to be some upside to our forecast of 9.9% GDP growth in 2021. One of the reasons behind this is the steady increase in spending on tendered infrastructure projects and on local government investment. Both factors should continue, as they are largely independent of the change in regime.

The new government will also inherit a moderately healthy fiscal situation. Tax revenue has been impressive throughout 2021, rising 42.8% in the year-to-May period. Since y/y comparisons are distorted owing to the lockdown in 2020, it is perhaps more significant that tax revenue in this period was also 11.6% higher than in the same period in 2019, and 18.6% greater than in 2018. Given that the reasons behind this outstanding performance—including rising income tax from mining companies, the rebound in demand and imports, and the digitalization of sales—do not seem to be temporary, we are modifying our fiscal deficit forecast for 2021 from 5.4% of GDP to 4.4%.

In addition, the new authorities will have to deal with inflation that is rising, albeit at a modest pace. In early July we raised our 2021 inflation forecast to 3.5%. This is above the BCRP target range ceiling of 3.0%. So, although the BCRP kept is reference rate unchanged at 0.25% in its monthly meeting on July 8, it is revealing that it eliminated from its forward guidance previous references to a “strongly” expansionary policy and its commitment to continue providing additional monetary stimulus as needed. This change in the narrative leads us to believe that the BCRP is preparing to begin tightening its rate sooner than we thought. As a result, we have modified our forecast schedule for the BCRP reference rate. Whereas before we were expecting the BCRP to raise its reference rate to 0.50% around mid-2022, we now expect this move to take place in late 2021. We also now expect the BCRP to continue raising its reference rate next year, ending 2022 with the rate at 1.0%. We make these changes with some hesitation, however, given that the BCRP will have a new board of directors in a few weeks.

Meanwhile, the PEN has stabilized somewhat in the FX market, albeit at a very high 3.90 to 4.00 range. This apparent stability may conceal centrifugal forces keeping the currency in that range, such as sound policy frameworks and strong institutions, and the FX seems vulnerable to breaking out from that range, though it’s not clear in which direction. On the one hand, the PEN is clearly out of sync with the dynamics of rising metal prices and Peru’s solid external account fundamentals. On the other hand, domestic USD demand continues to be strong, and could increase if fears that new government will not be market friendly are reignited. In that event, the government may long for a return to a Waiting for Godot environment.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.