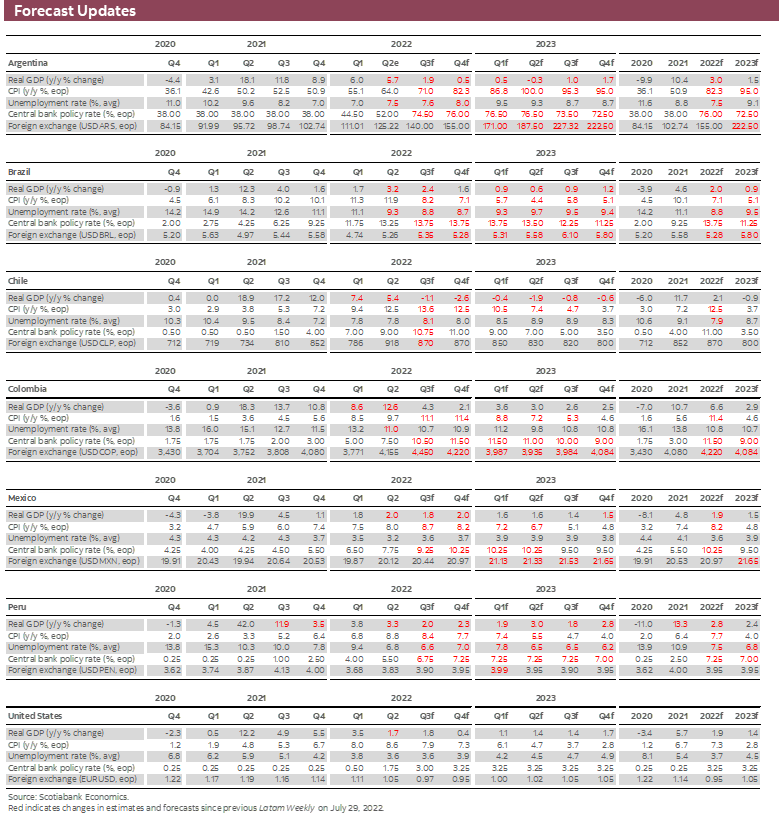

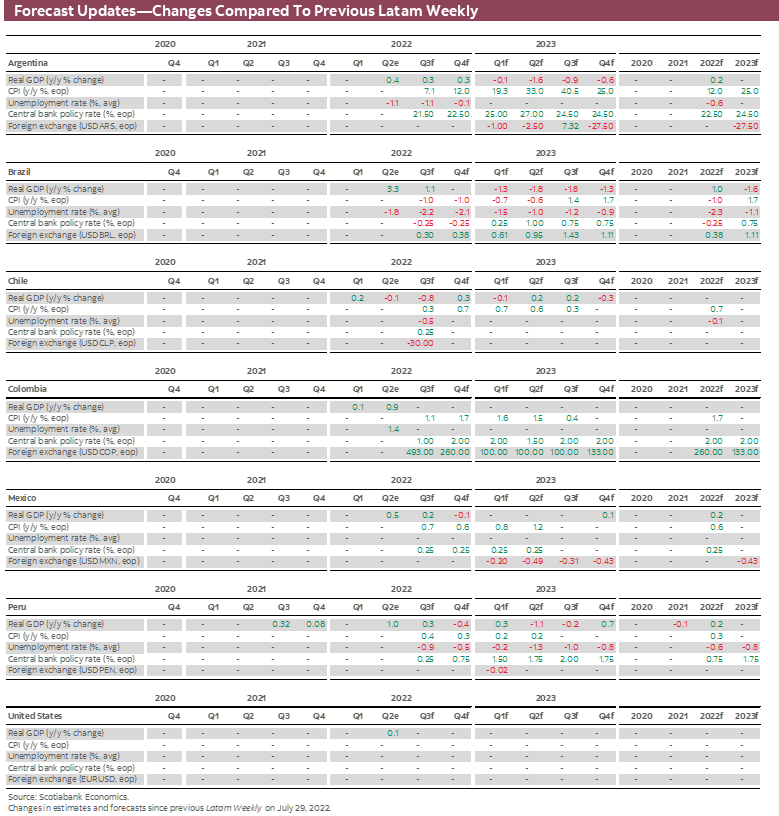

FORECAST UPDATES

- Inflation (and growth) surprises characterize recent Latam data releases. Scotiabank’s economists in the region have parsed recent developments to assess what they mean for near-term projections. See the full set of revisions in the forecast tables below.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- Persistent global price pressures have pushed inflation higher in the Latam region and around the globe. And while there may be limited signs of nascent disinflation in some countries, recent signalling by major central banks should deflate expectations of an early easing of global financial conditions. Far from it.

- Advanced economy central bankers this week signalled that, if anything, rates will go higher. Any easing in the stance of monetary policy is conditional on a period of sustained disinflation. In balancing risks, central banks have determined that the increased risk of global recession is outweighed by the long-term costs that would accompany the loss of inflation anchors.

- But with interest rates likely to stay higher, for longer, and the risks of global recession up, policymakers should keep a wary eye on risks to financial stability. The judicious use of macroprudential measures could assist central bank efforts to return inflation to target.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

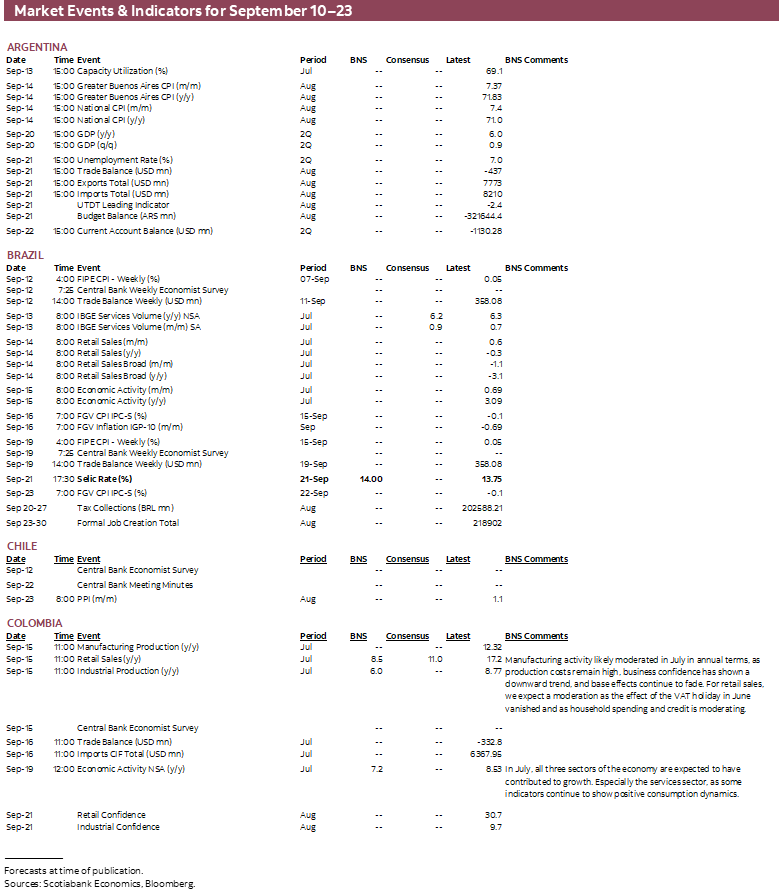

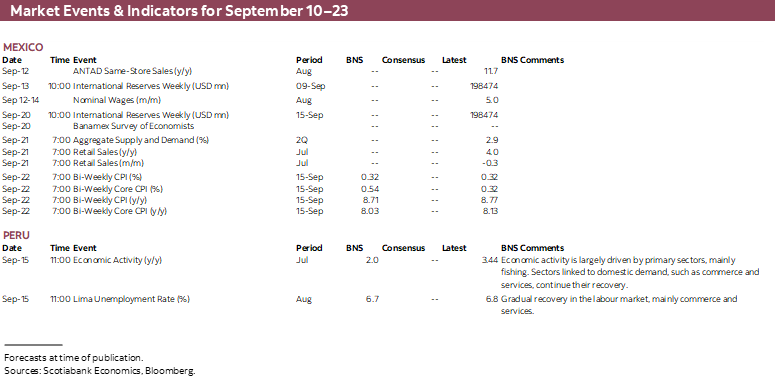

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period September 10–23 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: Gloomy and More Uncertain

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Back-to-back speeches by senior Fed officials this week, bookended by policy rate hikes by two major central banks, underscore key policy challenges and the risks to the global outlook.

- The first speech, by Fed Vice Chair, Lael Brainard, put a clear marker down in terms of the path of the US policy rate, which is already at the previous cycle’s peak and is going higher. Rates will remain elevated until there is clear and convincing evidence of sustained disinflation. The Bank of Canada and the ECB delivered the same message along with respective policy rate hikes of 75 bps.

- For the Latam region, the clear message is that global financial conditions will remain challenging given potential spillover effects on domestic inflation from exchange rate pass-through of a stronger US dollar.

- Interest rates that are higher, for longer, increase recession risks and pose potential threats to financial stability. This makes the second speech, by Fed Vice Chair for Supervision, Michael Barr, all the more timely. In the current context, the judicious deployment of macroeconomic policy measures could assist central banks achieve price stability targets.

- With increased risks of global recession and financial instability (and the threat of fragmentation of the global economy), it is little wonder that the IMF’s recent update to the World Economic Outlook is titled “Gloomy and More Uncertain.”

The week after the Labour Day holiday in North America not only marks the return to school, but also the end of summer holidays and the return to work. If back-to-back speeches by two senior Fed officials this week are any guide, it will be a busy autumn for financial markets. And while both speeches focused on the US economy (and were targeted at US audiences), their significance radiates beyond the US, with important implications for other countries, including those in the Latam region. Moreover, the Fed speeches come on the heels of an update to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook in late July that paints a decidedly bleak picture of global economic prospects.

The first Fed official to speak was Lael Brainard, the Fed’s Vice Chair. Her subject was the conduct of monetary policy, specifically “bringing inflation down”. The bulk of her prepared remarks reviews the various factors driving inflation higher, including pandemic-related supply-side shocks, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has led to sharp increases in global commodity prices, and opportunistic behaviour by firms exploiting the current environment to increase profit margins. However insightful these observations are, the part of Brainard’s speech that really matters to financial markets and Latam policymakers is her discussion of the future direction of monetary policy.

On this, she echoed the recent comments made by Fed Chair, Jerome Powell, which explicitly ruled out the possibility of an immaculate disinflation—one that doesn’t involve some “pain” to workers and businesses. Brainard noted that history teaches the dangers of premature easing. As she put it, “[the Fed is] in this for as long as it takes to get inflation down”. To reinforce the point, the Vice Chair reminded her audience that the policy rate has already been raised to the previous cycle’s peak, adding “and the policy rate will need to rise further”.

For Latam (and other) central banks, the message to take from all this is that global financial conditions are unlikely to ease anytime soon. As if to underscore this point, the European Central Bank hiked its policy rate 75 bps, matching recent Fed increases, while the Bank of Canada earlier in the week raised the Bank Rate by the same amount, which Scotiabank’s Derek Holt notes was viewed as more hawkish by financial markets positioned for a somewhat more dovish move. In raising their policy rates, both central banks followed the Fed in signalling that further rate hikes would likely be forthcoming.

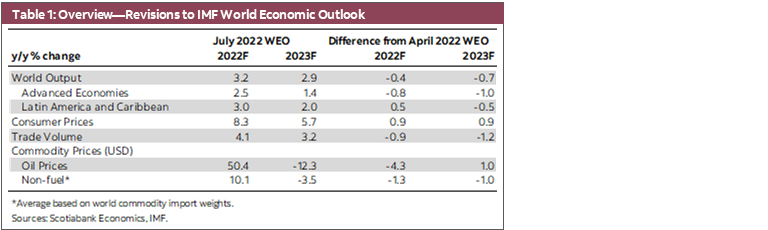

The need “to defend the inflation expectations anchor”, as Brainard put it, together with uncertainty with respect to the pace at which tighter financial conditions—not just in the US, but around the globe—weigh on aggregate demand and relieve price pressures, raises the possibility of global over tightening. This is just one of the risks to the outlook highlighted by the IMF’s WEO Update, which contains significant downward revisions to global growth and upward revisions to global inflation (table 1).

Interestingly, however, IMF growth projections for the advanced countries have been marked down by much more than those for emerging market and developing countries, including Latin America and the Caribbean. This result largely reflects the effects of commodity price shocks on countries’ terms of trade. Europe stands out in this regard, given its exposure to energy supply shocks emanating from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; if anything, recession risks there have increased since the IMF’s update. Some Latam countries, in contrast, stand to broadly benefit from a positive terms of trade shock, though this is not necessarily the case uniformly across the region. In fact, the region's growth prospects have been revised up by 0.5 percentage point in 2022 as result of a more robust recovery in the larger economies (Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Chile).

But with higher inflation threatening to unleash inflation expectations, containing price pressures must be the priority. This is the case around the globe. The global nature of the problem is reflected in broadly similar upward revisions to the IMF’s inflation projections across regions and country classifications. And for Latam countries, the tightening of US monetary policy has put pressure on domestic currencies, with consequent risks of pass-through inflation coming from exchange rate depreciation.

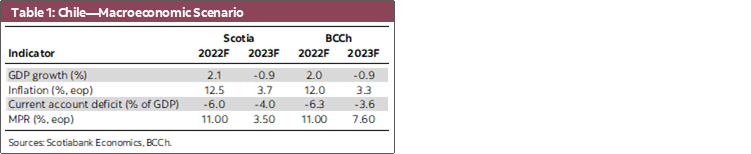

These forces are playing out in recent Latam developments. In Chile, for example, the BCCh’s recently published Monetary Policy Report revised upward expected growth for 2022 to broadly mirror the projection of Scotiabank’s team in Santiago, while bumping up inflation. The report follows a 100 bps hike in the policy rate that surprised markets. However, with output expected to contract in 2023, creating disinflationary pressures through a negative output gap in Q4-2022, our experts believe it will be difficult for the central bank to avoid cuts to the monetary policy rate as inflation trends down.

In Colombia, meanwhile, inflation in August was well above expectations, highlighting risks to the inflation expectations anchor, and putting presure on BanRep to recalibrate (upwards) it’s forthcoming rate decision. And as our economists in Bogota highlight in the country notes below, output growth remains strong, with a rising output gap that peaks at year-end. Mexico’s inflation also came in higher than expected in August, accelerating from 8.15% y/y to 8.70%.

The situation in Peru, where year-on-year inflation has eased for two consecutive months, is different. Scotiabank’s experts in Lima anticipate price pressures to continue ease, albeit at a gradual pace. That said, there is little room for complacency, and additional price shocks would have to be met with decisive action.

The second noteworthy speech by a Fed official this week was given by the Fed’s new Vice Chair for Supervision, Michael Barr. While his remarks focused on domestic regulatory issues, specifically a “holistic” review of existing capital regulations, Barr’s comments underscore the importance of financial stability. With recession risks undoubtedly higher than just a few months ago, and interest rates likely to move higher still, threats to financial stability have increased. (The IMF staff point out, for example, that the risk of a recession in the G7 countries extracted from asset prices is nearly 15 percent, and nearer to 25 percent in Germany.) The good news here is that capital buffers of financial institutions in the US and around the globe are likely significantly higher than prior to the global financial crisis.

Nevertheless, risks remain. Higher interest rates entail losses on financial intermediation as loan origination stalls and default rates rise, an effect likely exacerbated by high levels of indebtedness—one of the many legacies of the pandemic. The risks may be particularly pronounced where businesses have large unmatched balance sheets reflecting borrowing in US dollars while their revenues are denominated in domestic currency. In this uncertain environment, authorities may want to carefully consider the active use of macroprudential policies. At the same time, for countries suffering from the terrible trifecta of high debt burdens, negative terms of trade shocks from higher commodity prices, and lower world trade volumes (table 1, again), the risk of severe debt distress has likewise increased.

As highlighted in previous editions of the Latam Weekly, another risk to the global outlook comes from the possible fragmentation of the global economy into geopolitical blocs. While declining global trade volumes pre-date Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the risks attached to this scenario have clearly increased since the Kremlin’s blatant challenge to the rules-based international order that has prevailed over the past six decades. A process of “de-globalization” would likely entail significant efficiency losses, though some re-shoring or near-shoring of production that enhances the resilience of supply chains could be a rational response to the supply-side shocks unleashed by the pandemic. A shortening of supply chains could potentially benefit Latam countries, especially Mexico. But as Scotiabank’s team in Mexico City point out below, exploiting these opportunities is not assured, and sound policy frameworks, including with respect to foreign investment, and strong legal, fiscal, and monetary institutions are needed.

With increased risks of recession, higher inflation, threats to financial stability, and the potential fragmentation of the global economy, policymakers in the Latam region as well as global investors would do well to heed the IMF’s assessment of global prospects. In their recent update, Fund officials put the risks to the global economy in remarkably stark terms: “The risks to the outlook are overwhelmingly tilted to the downside.” In this respect, it is little wonder that the IMF WEO July Update was titled, Gloomy and More Uncertain.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Political Uncertainty Gradually Dissipates; We Maintain our Macroeconomic Scenario without Relevant Changes

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

COVID-19 SITUATION IN CHILE

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has dropped in recent days, thanks to a decrease in the test positivity rate to 10%. For now, occupancy rates of ICU beds and COVID-19-related death rates are stable at low levels. Meanwhile, the vaccination campaign has reached 93.1% of the eligible population. The rollout of booster (third) doses continues—reaching 15.6 million people—and the new booster dose (fourth) is in progress—with 11.3 million people covered. In this context, government confirmed a new booster dose (fifth) for this year.

MARKET FRIENDLY RESULT OF THE REFERENDUM

On Sunday, September 4, the proposal for a new constitution was rejected by 62% of voters, compared to 38% who voted in favour. The result was similar across the country, with the rejection option prevailing in all regions, including the Metropolitan Santiago Region (55% against 45%). The approve option won in only 8 of 346 municipalities, 5 of them in the Metropolitan Region. The plebiscite saw a high turnout (85%; 13 mn voters), since participation was mandatory.

Looking ahead, the design of the new constitutional review mechanism could have an additional positive impact on Chilean asset prices. We expect additional disinflationary pressures, appreciation of the currency and less headwinds from structural reforms if a national agreement is reached for a bounded constitutional assembly or if a selective group of Congresspeople is tasked with writing a new proposal.

HEALTHY ADJUSTMENT IN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

According to the central bank (BCCh), GDP expanded 5.4% y/y in the second quarter of 2022. For its part, monthly GDP expanded 1.0% y/y in July but contracted -1.1% m/m owing to the poor performance of services, which fell 1.7% m/m. In our view, the downward adjustment in activity is a healthy development, conditional on continued fiscal consolidation and in a context of economic fragility and a less dynamic labor market. Starting in August, economic activity will likely begin to show year-on-year declines that will last until at least the second part of next year. Considering all of the above, we maintain our GDP growth forecast of 2.1% for this year and reiterate our forecast of -0.9% for 2023.

CPI inflation increased 1.4% m/m in August, standing at 14.1% y/y. In our view, this figure includes an important part of the recent depreciation of the Chilean peso (CLP), as well as the inertial effects of historically high inflation. The broad diffusion of price increases across goods in the CPI basket, where nearly 70% of the items registered m/m price increases in August, support this contention. According to our projections, this is likely to be the highest level of year-over-year inflation in this cycle (14.1% y/y). We project CPI inflation at 12.5% y/y for December 2022 and 3.7% y/y for December 2023.

Considering the above, we continue to see a more intense disinflationary process than is contemplated by the market, especially after a plebiscite result that will lead to moderate structural reforms and a less favorable political scenario for additional fiscal stimulus.

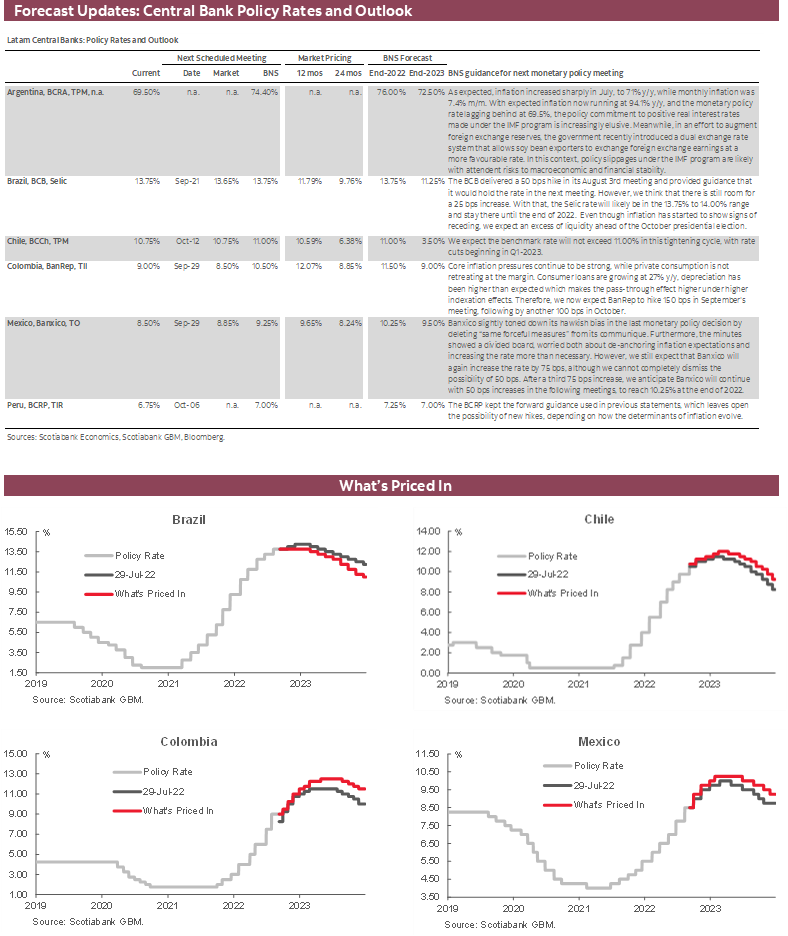

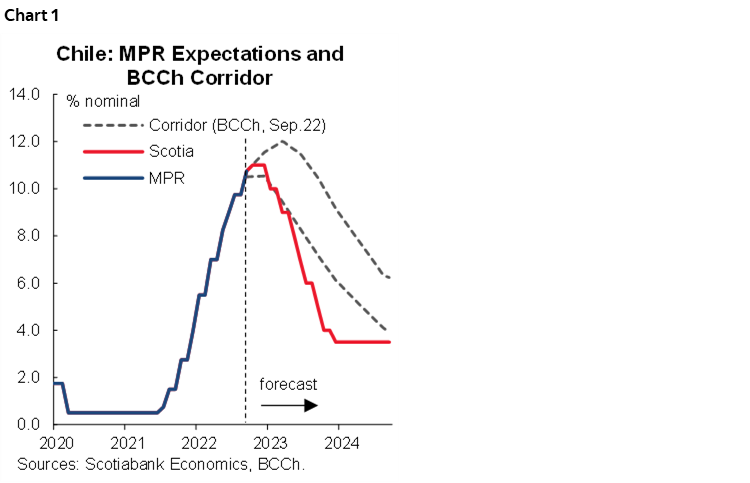

BCCH RAISES THE BENCHMARK RATE BY 100 BPS, UP TO 10.75%. WE ANTICIPATE AN AGGRESSIVE PROCESS OF CUTS NEXT YEAR

On Tuesday, September 6, the BCCh increased the benchmark rate by 100 basis points (bps), above market expectations, changing its bias to neutral (from hawkish in the last meeting). We see a risk that the BCCh could bring rate cuts forward (before Q1-23) and we continue to think that the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) will range between 3.5% and 4% by December 2023. The cuts in the MPR (or at least a dovish bias) could start as soon as the December 2022 meeting (chart 1).

For its part, on Wednesday September 7, the BCCh published the Monetary Policy Report for September, whose scenario was close to the one Scotia have since few weeks ago in terms of GDP growth, inflation and current account deficit (table 1).

A LOOK AHEAD

In the next fortnight, the central bank will release the minutes of the September’s Monetary Policy meeting (September 22). At the same time, the government is expected to take the pension reform to Congress.

Colombia—New Terminal Rate Expected

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9166 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Maria Mejía, Economist

+57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

maria1.mejia@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Senior Economist

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9400 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Worldwide Inflation has been more persistent than markets expected owing to both supply-side shocks and demand pressures that have put central banks around the globe behind the tightening curve. Of course, Colombia is not exempt from these effects. Inflation hasn’t peaked; on the contrary, the last print showed an unexpected acceleration of price increases across the CPI basket. In fact, core inflation increased on average 54 bps per month in the year to date up to August, from 3.44% y/y in December 2021 to 7.8% y/y in August. At this rate, a scenario with headline inflation above 11% by year-end is possible. This is worrisome given that indexation effects will slow disinflation. As a result, we don’t anticipate convergence to a lower price path until after H1-2023.

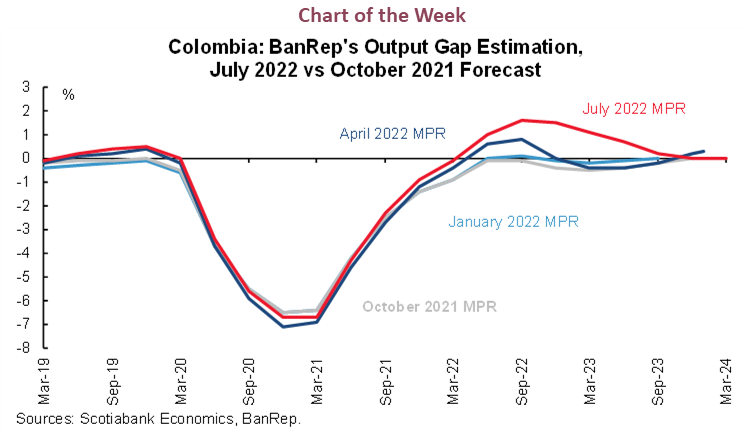

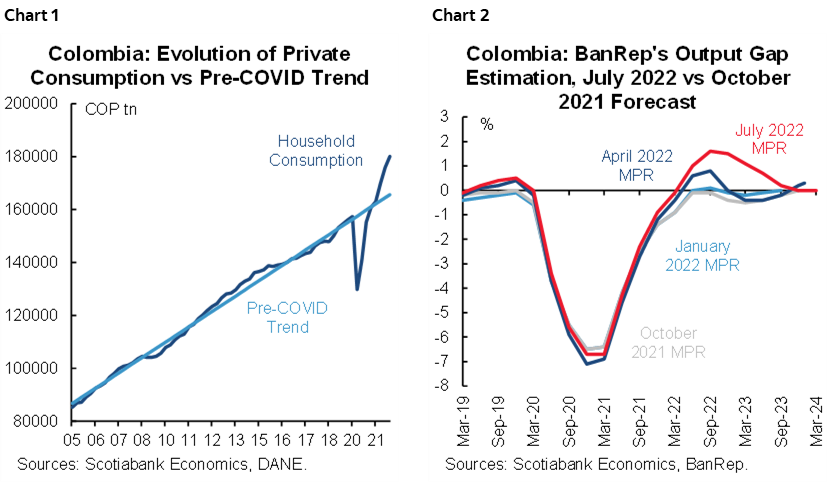

Meanwhile, economic activity appears to remain strong, especially in terms of private consumption. GDP grew 12.6% y/y in Q2-2022, while private consumption expanded 14.6% y/y, pushing household consumption 12% above its long-run trend excluding the pandemic (chart 1). In the wake of these results, BanRep’s staff estimates that output gap is now positive (chart 2), while leading indicators suggest that private consumption for the third quarter remains excessively high, further raising the output gap. (Consumption credit is growing at 27% y/y, though non-performing loans are modest and stable at about 4.5%.) In addition, energy demand continues to signal economic expansion; and while consumer confidence has fallen, the willingness to buy durable goods is holding up despite FX depreciation. Given this suite of indicators, GDP growth above 7% this year is possible, despite weak investment, driven by private consumption that is worryingly high.

On the external side, the only certainty is that interest rates will be higher for longer owing to more persistent inflation.

The key takeaway is that every single element of the BanRep’s reaction function points to continuing hikes to the policy rate, with a higher terminal rate. Our model has a smoothing parameter that usually does a good job of replicating BanRep’s behaviour. In the current environment, however, we think the smoothing factor should be lower and that a more forceful response to current inflation is the right way to go. We are therefore updating our terminal rate from 10% to 11.5%, with a 150 bps hike in September followed by a 100 bps increase in October. While we think that central bank cannot cut the policy rate until Q3-2022, once disinflation is clearly on track, in our view, the policy rate will be 9% at end-2023.

Mexico—Near-Shoring Story… It’s Complicated

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

+52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

There are echoes of what happened a century ago in today’s political economy. Before Brady Bonds were launched in the 1980s, and the ensuing explosion in the issuance and trading of emerging market bonds, we need to go back 100 years to the boom in trading of Egyptian Suez Canal Bonds and Mexican and Argentine Railroad Bonds to find a comparable analogue with respect to the presence of developing economies in global capital markets. That earlier integration of global financial markets occurred in tandem with a remarkable period of trade integration (1870–1914), which has been well documented by academics. Like that earlier epoch, the 1970–2010 period saw trade as share of global GDP more than double, before retreating over the past 10–12 years. Besides these macro-financial historical rhymes, the rise of populism, the 1918 Spanish Flu/COVID-19 pandemics, the parallels between the 1907 and 2007 crises, the roaring 20s, income and wealth polarization, as well as interesting characters like Henry Ford and Elon Musk, all provide rich material for a lengthy paper, or an enthralling fireside chat, on the parallels between then and now. But this is not the subject of this note.

Rather, we want to focus on how Mexico’s economy is being affected by the shifts in global trade and investment flows. Attention is increasingly being focused on the risk of fragmentation in the global economy. Fortunately, this time around, we have not had a World War that is driving the deglobalization, though Russia’s invasion of Ukraine clearly undermines the rules-based international order that has provided the foundations on which globalization has been built over the last six decades. In hindsight, it seems that a series of shocks triggered a re-think of supply chain globalization by business leaders—spurred along with help from some populist leader’s shocks to the trade’s legal infrastructure. These shocks include:

- The earthquake that devastated Fukushima in March 2011, which was a severe blow to the global auto sector and damaged global supply chains. This shock was among the first in a series of disruptions to global supply chains.

- The Trump-China trade dispute, which introduced additional uncertainty to global supply chains and may have accelerated the regionalization/deglobalization of the global economy.

- The COVID-19 pandemic and related border lockdowns that have provided further evidence that supply chain globalization has many benefits, but also entails risks.

- The latest major blow in this series has been the conflict in Ukraine, arriving at a time when the global economy was already struggling with pandemic related disruptions.

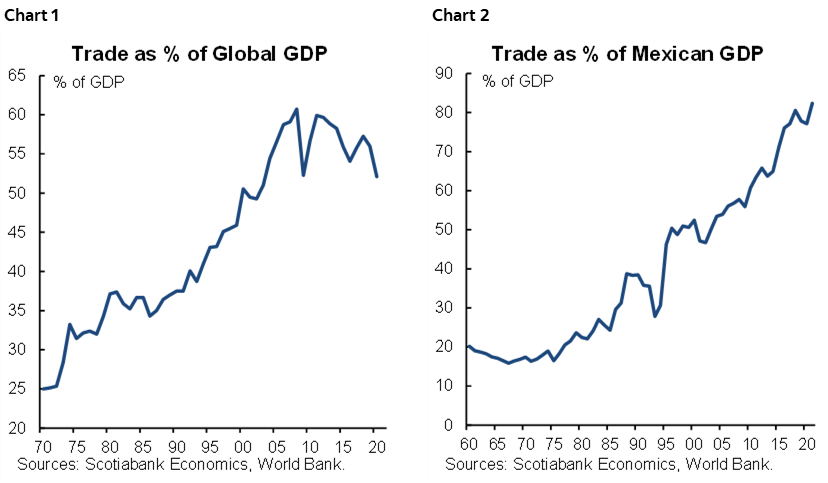

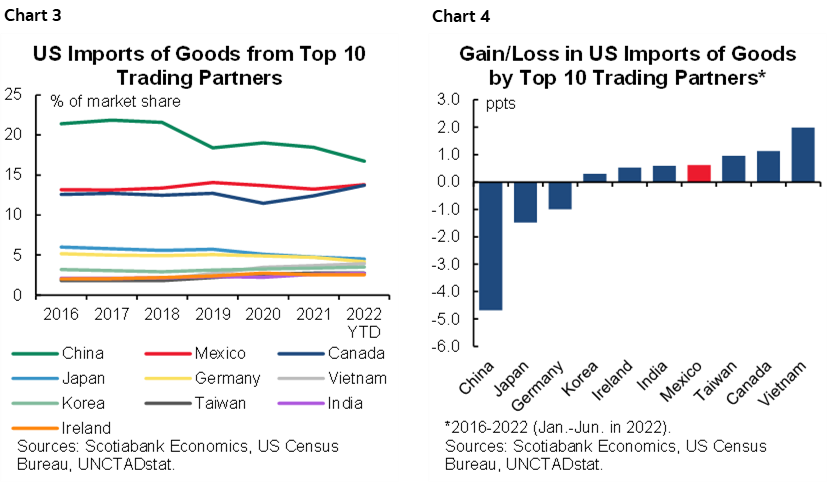

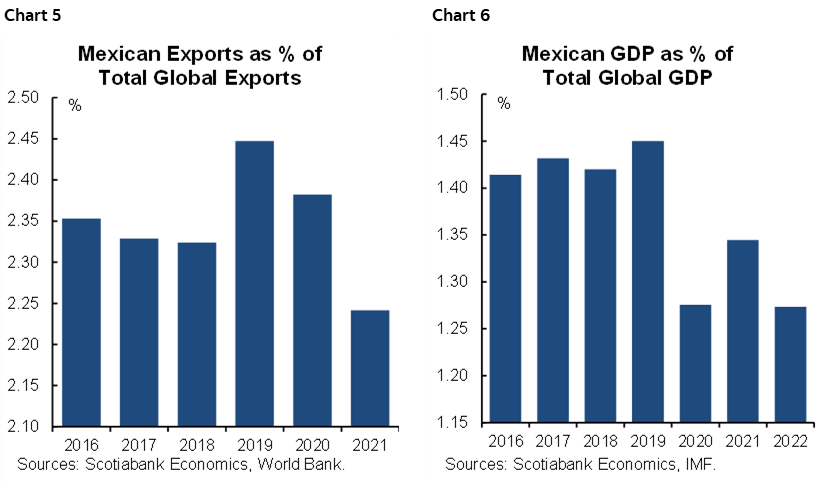

While there is a myriad of contributing shocks, the effects of which are difficult to disentangle, the bottom line is that trade rose from around 25% of global GDP to 60% in the 1970-2010 period and has now dropped 8 percentage points to around 52% of global GDP (chart 1). Interestingly, at first glance, Mexico seems to have missed the plotline. Despite that drop in trade as a share of global GDP, Mexico’s trade has continued to gain ground as a share of its economy (chart 2). Does this mean Mexico’s nearshoring boom is happening? The answer to this question is complex.

In terms of market share, there is a clear downwards trend to China’s market share in US imports since the Trump-China trade dispute (chart 3). China has lost nearly 5 percentage points of market share in US imports since 2016. However, much of that loss by China seems to have been picked up by other Asian economies such as Vietnam, Taiwan, and India (chart 4). Three of the 5 largest market share gains in US imports since 2016 have been achieved by Asian economies. In that same time span, Canada has gained almost twice as much share in US imports as Mexico has (1.1 percentage points compared to 0.6).

In a world with shrinking trade, Mexico has not really been the outperformer in the US market. It has gained market share, but only 60 bps in six and a half years. This means that Mexico has only captured 13% of the US market share lost by China. By contrast, Vietnam has captured around 40% of China’s lost US import share. So why are exports rising as a share of Mexico’s GDP? One possibility is that Mexico is starting to diversify, and its exports are going further abroad, and the country is decoupling from the US. That could be part of the explanation, but it is also true that Mexico’s share of global exports hasn’t had a material increase over the same time-span, and in 2021, Mexico’s share of total global exports actually contracted (chart 5). Sadly, part of the explanation of Mexico’s rising exports, is that Mexico’s economy has not kept up with the world’s and its share of global GDP has dropped from around 1.40% in 2016 to around 1.27% in 2021, roughly a 10% decline (chart 6).

In terms of trade flows, the data suggests that for Mexico, nearshoring has been an opportunity on which it has only marginally capitalized. However, we can also argue that it has also been a saving grace, as the export sector—despite its lack of growth from an international comparison perspective—has been the pillar that has propped up the economy, offsetting declines in some of the domestic demand components, such as investment, which has dropped from around 23% of GDP in the 2010–2018 period, to a level likely closer to 20% in 2022.

Looking ahead, there are two angles to Mexico’s nearshoring story that we intend to explore in coming editions of this publication:

- The first is investment. Mexico’s total domestic investment has dropped materially since 2018, and the country’s share of global FDI has also declined. This seems to imply that the nearshoring story is a bit overblown. However, the latest FDI print for Mexico (22Q2) provided positive news, as we saw a large inflow. It remains to be seen whether this was a temporary upswing due to pent-up investment delayed by the pandemic, or a sustainable rise. As we get more consolidated data from other countries, we can see whether this was a global rise reflecting delayed projects coming on stream, or whether Mexico’s share of global FDI really rose as we moved into this year’s summer.

- The second point we are going to explore is how both trade and investment are evolving by region. By looking at the country’s regions we can find the success stories in both global trade and investment. The reality is that within Mexico there are regions and sectors which have been, and we expect to continue to be, very dynamic and competitive. However, there are other parts of the country that have materially underperformed.

Peru—Assessing New Fiscal Measures

Guillermo Arbe, Head Economist, Peru

+51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Recent developments have brought fiscal policy to the fore in Peru. The main event was the new 36-point stimulus plan announced by the, also new and quite vocal, Minister of Finance, Kurt Burneo. We’ve already noted (see Latam Daily, August 29) our view that Minister Burneo is seeking to get a derailed economic management back on track by restoring business confidence and getting private investment moving, especially with respect to infrastructure projects, and pursuing greater public investment.

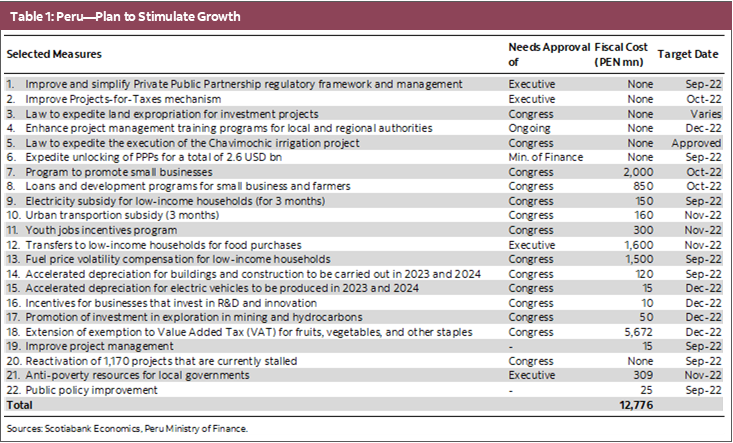

The ImpulsoPerú plan was released on September 8, a 36-point. Burneo hopes that his program will not only stimulate jobs creation, investment and growth in the short-term, but also reverse the long-term downtrend in potential GDP by fostering greater competitiveness and by bridging the infrastructure gaps. All this while not generating inflation nor putting fiscal accounts at risk.

In numerical terms, the plan earmarks PEN 5.3 bn (0.55% of GDP) in public investment to be spent mostly in 2023, and another PEN 5.2 bn (0.54% of GDP) for measures to stimulate private spending (table 1). Adding odds and ends, the total fiscal impact, either through spending or forgone fiscal income, amounts to nearly PEN 12.8bn. The intention is to create over 200,000 jobs over the next 12 months and increase GDP growth by 0.6 percentage points in 2022, and by 0.8pp in 2023.

So, will it work? Probably not in 2022, as we are too far into the year for the measures to be executed and/or to have a significant impact. The impact in 2023 and after will depend on several factors, not all of which are under the control of the Ministry of Finance.

The first thing to note is that, although PEN 5.3 bn in public investment seems like a lot of money, much of it does not really consist of new resources, but, rather, represents a promise to spend properly and expediently in projects that are already in the 2023 budget, and to reactivate projects that have become stalled over time.

Furthermore, Peru does not have a good track record in execution in fiscal stimulus plans, owing to low spending management capabilities at all government levels. This issue is enhanced due to coordination deficiencies within the current cabinet, and to the change in regional governments following elections in October.

To complicate matters further, some of the initiatives will require congressional approval, and the level of confrontation between the Executive and Congress is too high to guarantee success. Just this week, Minister Burneo complained about verbal mistreatment by members of Congress during discussions around the 2023 budget.

On the plus side, the fact that the Ministry of Finance is relying on the private sector for infrastructure investment through PPPs is a positive. The plan also contemplates extending the accelerated depreciation tax benefit for mining companies and expanding the mechanism to investment in construction and in Research& Development. This will need to be approved by Congress first, however, and one wonders if it will be forthcoming.

The intention to expand business tax benefits is probably in part to help restore confidence. However, building business confidence will require a change in the political environment and in the overall anti-business narrative that has been emerging from President Castillo and the cabinet head Aníbal Torres lately.

The ImpulsoPerú plan was made public against a backdrop of expectations that GDP growth has begun to slow. On September 15, GDP growth for July will be released. We expect a soft start to H2 of 2%, y/y, GDP growth, as preliminary information for July is generally point to a slowdown. Agriculture fell 1.5%, y/y, and mining GD plunged 5.8% y/y in July. One could argue that electricity, up 4.8% in July, tells a different story, but the increase relied heavily on the start-up of the Quellaveco copper mine, and was not representative of demand. The bottom line is that growth going forward is likely to be well below the 3.5% GDP growth during the H1 2022.

Having said that, the slow down in growth H2 is coming off better than expected growth of 3.3% y/y, in Q2. Based on strong Q2, and on the impact of pension fund withdrawals on consumption’s historical trend, we are raising our forecast for full-year 2022 growth from 2.6% to 2.8%. We have not factored in the Burneo package, which as noted above comes too late in the year to have much impact. However, we will need to take a fresh look at our GDP forecast for 2023 (2.4%) once we delve more deeply in the stimulus package and its impact.

A key piece of the growth puzzle will be provided on September 15 with the release of June–August unemployment data for Lima. We expect unemployment to continue hovering in the vicinity of the 6.8% level in previous periods (ending in July and in June). However, the risk is to the downside, as public investment rose significantly in August, as the October elections near. To put the 6.8% figure into context, the number compares well with pre-COVID-19 levels (unemployment averaged 6.6% in 2019). The robust job figures are in line with robust consumption, but one does wonder where the jobs are coming from, given such low investment.

A final note on politics. Congress must elect a new President of Congress (may have done so by the time you are reading this) after the former President of Congress, Lady Camones, was ousted on September 5 by her colleagues. This occurred after an audio recording surfaced in which she appeared to be negotiating gerrymandering voting districts to benefit her party (Alianza para el Progreso, APP) in the regional elections in October. Congresswoman Camones lasted little over a month as President of Congress. Her replacement will have a crucial role in defining the, normally contentious, relationship between Congress and the Executive.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.