FORECAST UPDATES

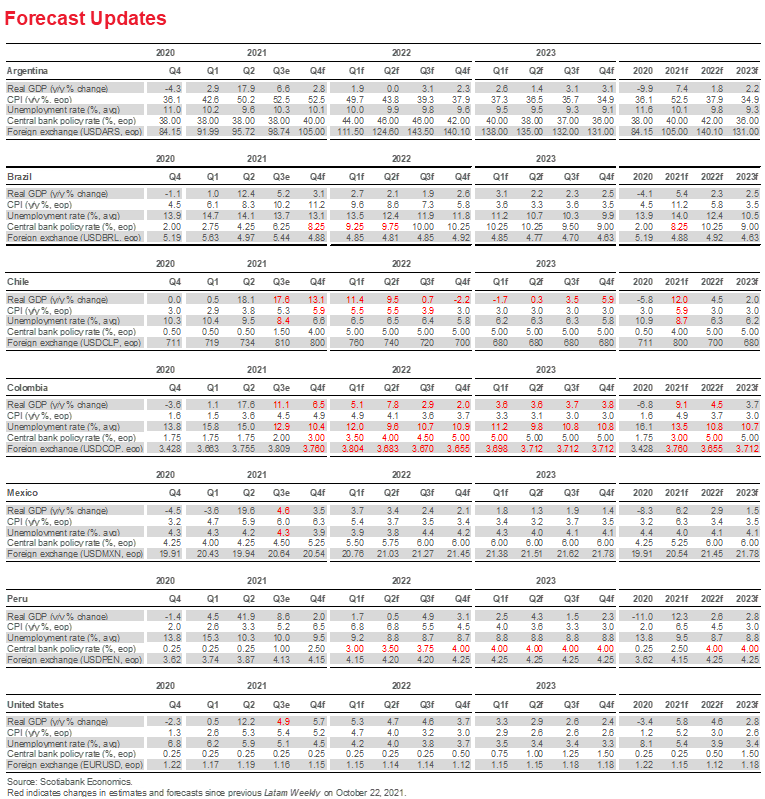

- Higher inflation and stronger growth numbers have led our analysts to revise key forecasts. Additional tightening is now expected in Brazil, Colombia and Peru. See the table below for the full set of revisions.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

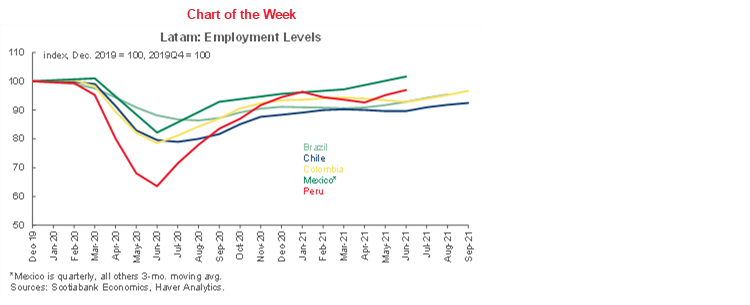

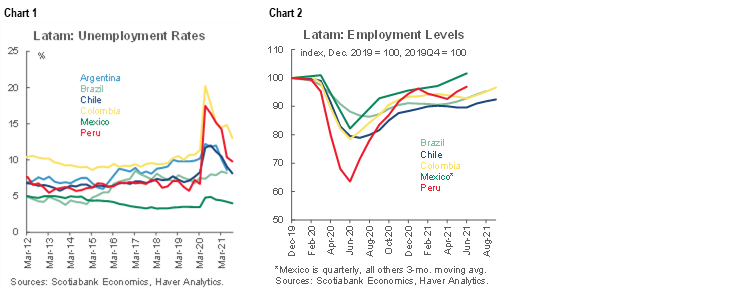

- Latam economies suffered severe employment losses early in the pandemic as public health emergencies were declared and economic lockdowns were introduced.

- Unemployment rates soared. And while employment has gradually recovered across the region, only Mexico has fully recouped its losses. Workers have re-entered the labour force as employment has increased, so that unemployment rates remain above pre-pandemic levels.

- Understanding labour market dynamics—especially differences between formal and informal sectors—could provide clues to the region’s economic prospects.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

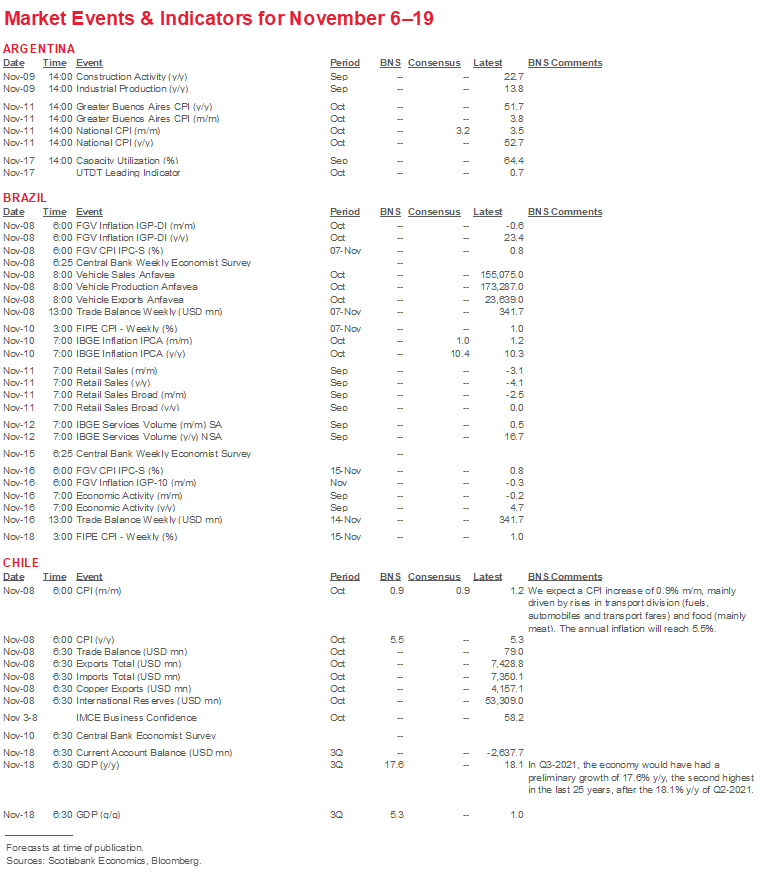

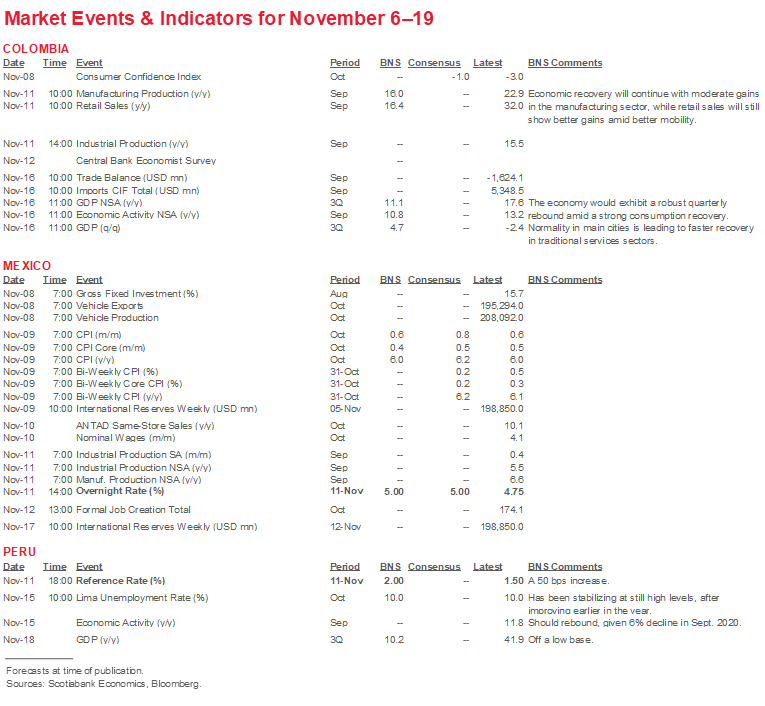

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period November 6–19 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: Labour Markets in Recession and Recovery

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Strong US jobs numbers have focused attention on labour market developments and what they might imply for the calibration of monetary policy.

- The Latam region experienced a particularly pronounced decline in employment early in the pandemic. Employment has gradually recovered, but unemployment rates remain above pre-pandemic levels.

- Structural features of Latam labour markets, especially the importance of informal employment, may provide insights into the region’s economic prospects going forward.

LABOUR MARKET DEVELOPMENTS AND ECONOMIC PROSPECTS

Strong US job numbers released November 5 are encouraging for economies looking for external demand to help fuel their recoveries, Latam countries among them. And as Scotiabank’s Derek Holt notes here, the US October employment figures reveal that the prior “soft patch” wasn’t so soft after all. His key takeaway—stronger wage growth, coupled with uncertainty about the near term evolution of the labour force participation rate, militate for the exercise of caution in targeting pre-pandemic gauges of full employment in calibrating monetary policy. Holt’s caveat is timely.

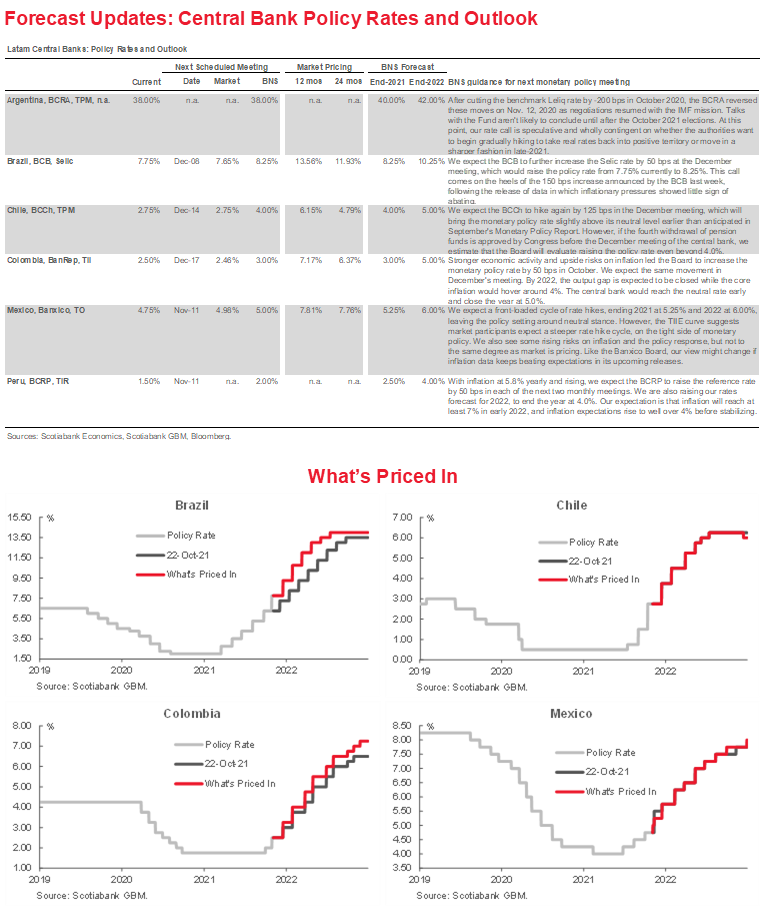

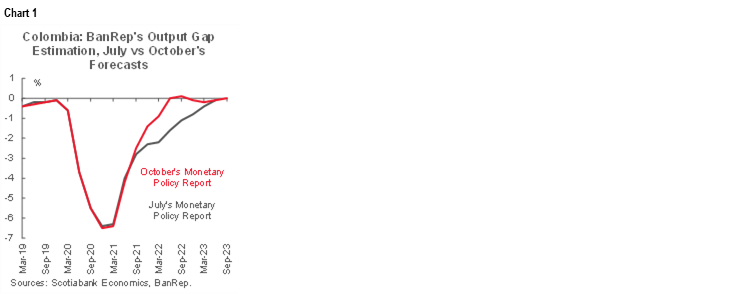

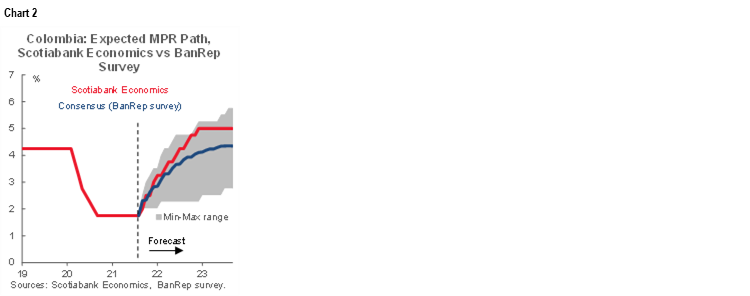

Across the Latam region, inflation-targeting central bankers that have seen inflation spike look to output gaps to gauge the pace of their policy responses. In Colombia, for example, BanRep’s latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR) shows the output gap is now expected to close by mid-2022 in the wake of a vigorous rebound in output. As the discussion in the country notes below highlights, in the previous MPR that milestone was not expected to be reached until 2024. That revision has prompted our team in Bogota to call for a 50 bps rate hike by BanRep in December (up from 25 bps), to 3%, with a 5% policy rate at end-2022 (up from 4.5%). Similarly, stronger growth in Peru and inflation pressures have led our team in Lima to raise their forecast for the monetary policy rate, which is now expected to be raised 50 bps in each of the next two monetary policy meetings. In Chile, meanwhile, GDP is on track to grow by 12% in 2021 (see discussion below).

These signs of robust recovery are unambiguously good news. But the unique nature of the COVID-19 recession and its impact on labour markets may lead to somewhat different recoveries than in previous cycles; understanding labour market dynamics in recession and recovery could aid in the setting of monetary policy in the face of increased uncertainty. Arguably, insights into labour markets are especially important in the current context of supply chain disruptions and supply bottlenecks that exacerbate the challenge of determining whether current price pressures are a temporary phenomenon or a harbinger of persistent high inflation.

The starting point is to recognize that Latam labour markets were especially hard hit by the pandemic. Work done by the IMF* documents the extent of the dislocation: most significant, employment in the region fell sharply; more so than other emerging markets and advanced economies. Employment declined between 20–30 percent across much of the region in the early stages of the pandemic as lockdowns took effect in March 2020. Brazil experienced the lowest decline, reflecting the government’s emergency employment protection program. In Peru (Lima, for which numbers are available), the decline was far greater.

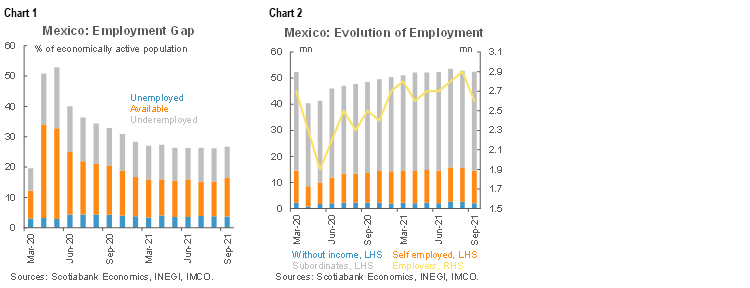

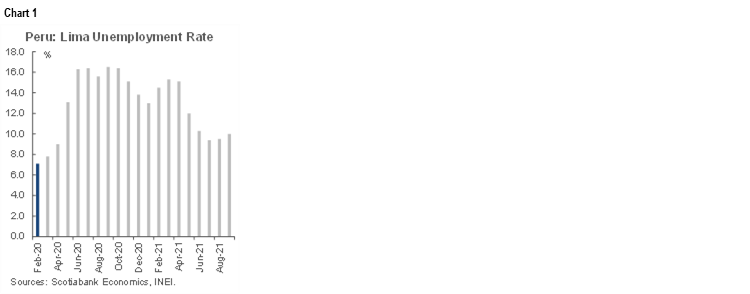

The impact of these job losses is evident in the steep rise in unemployment rates across the region (chart 1). Employment recovered somewhat through the summer of 2020 as mobility restrictions were eased. Since then, however, employment gains have been more modest, with only Mexico having returned to its end-2019 employment level (chart 2).

Meanwhile, the labour force has grown, as measures to contain COVID-19 slowed the transmission of the virus, mobility restrictions were relaxed, and economic activity picked up. As a result, while unemployment rates have come down significantly from their peaks in much of the region (progress has been much slower in Brazil), they remain stubbornly above pre-pandemic levels.

At the same time, as the discussion in the Mexico and Peru country notes below makes clear, women were particularly hard hit by the collapse of employment early in the pandemic, bearing a disproportionate burden of the adjustment. And while the some of the gender employment gap has been closed, more progress is needed.

The IMF study cited above also found that in contrast to other recessions, the contraction in employment was larger than the contraction in GDP. These stylized facts are likely explained by the fact that a larger share of workers in the Latam region are employed in occupations that were not amenable to remote working arrangements (e.g., mining) and in “contact-intensive” sectors, such as tourism, when the pandemic was declared. Not surprisingly, the imposition of public health mandated lockdowns had a disproportionate effect on these workers.

To some extent, the severity of the employment losses in Latam countries reflects underlying structural characteristics of the labour market, particularly the large share of workers in the informal sector. These are typically individuals with low skill levels, lacking long-term attachment to their employers through deferred benefits (such as pensions) and access to promotion ladders that support the accumulation of firm-specific human capital. The absence of these attachments implies that firms are more likely to terminate employment in the face of declining demand; in the case of the COVID-19 recession, employers have little incentive to maintain an ongoing relationship with their workers.

In contrast, workers in the formal sector benefit from the accumulation of firm-specific human capital that makes them more valuable to the firm than a new hire. The skills embodied in this human capital may reflect investments by the firm in training the worker, or simply the increased proficiency that comes with a longer tenure. Regardless, the upshot is that the firm has an incentive to retain these workers through long-term financial incentives and by engaging in labour hoarding.

Labour hoarding is the practice of keeping workers on the payroll despite a temporary decline in sales. Of course, the longer that the downturn in sales persists, the more likely that the firm will be forced to layoff workers. In any event, the practice of labour hoarding implies that employment levels of workers in the formal sector may be less flexible than those of informal workers. Moreover, changes in employment levels are more likely to be less responsive to changes in output levels.

The COVID-19 recession was unlike any other downturn, however, in that it was triggered by a public health emergency; not the build-up of macroeconomic imbalances or some external economic shock. In this respect, the pandemic constitutes a systemic shock that swept across all regions, affecting all countries and all sectors. The nature of the shock accounts for the unprecedented policy responses across the globe.

Included in those responses are measures that could help preserve the stock of firm-specific human capital by supporting individuals through cash payments and unemployment insurance programs. Brazil and Chile standout in terms of these responses, but other countries in the region have also introduced a range of programs to assist workers. These policies have cushioned the blow of employment losses for the most vulnerable, including those in the informal sector. But they may also provide firm foundations for future growth by allowing individuals in the formal sector to “ride out” the recession, awaiting the reopening of the economy.

This effect could have important implications on future economic performance. For example, while the informal sector is marked by more flexible labour arrangements, such that individuals employed in may be the first to lose their jobs and the first to be hired back as the economy reopens, it is also characterized by low productivity and low value added. Formal employment arrangements, in contrast, are more likely in high productivity, high value added sectors. In this respect, the Latam region’s medium-term growth prospects may be dependent on the recovery of formal sector employment. A key unknown in this context is the resilience of firms to higher debt burdens taken on during the recession once the extraordinary monetary and fiscal policy measures are unwound.

* Latin American Labor Markets during COVID-19 by Takuji Komatsuzaki, Samuel Pienknagura, Carlo Pizzinelli, Jorge Roldos, and Frederik Toscani. International Monetary Fund, October 2020.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—GDP is on Track to Grow 12% in 2021—High Labour Demand and Employment Recovery

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

56.2.2939.1495 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has continued to rise in recent days, reaching its highest level in four months, reflecting an increase in the positivity rate to 3.1% in the last week, despite the vaccination campaign having reached 90% of the eligible population. The occupancy of ICU beds and the COVID-19-related death rates slightly increased but remain at low levels. Meanwhile, the rollout of booster (third) doses keeps moving forward, reaching almost 5.9 million people.

Thanks to the success of the vaccination program, workplace mobility had surpassed pre-pandemic levels. However, on Monday October 25, the Ministry of Health announced that the Santiago Metropolitan Region took a step back in its reopening “Paso a Paso” plan because of the increase in COVID-19 cases. The region, which represents approximately half of Chile’s GDP and population, moved back from “Initial opening” phase to “Preparation”, resulting in greater restrictions for some activities, mandating greater social distancing in restaurants and limiting the number of customers in commercial enterprises.

In Congress, on Tuesday October 26, the Senate Committee on Constitution, Legislation and Justice gave preliminary approval of the bill for the fourth 10% pension fund withdrawal. On November 10, the Senate will debate and vote on the bill, where it needs 25 votes to be approved (a two-thirds majority). If approved, the bill will go back to the same Senate Committee to debate and vote on each individual article. Lastly, a committee made up of Lower House and Senate members would work out any differences between the House and Senate versions of the bill. The resulting bill would then return to the House and Senate for final approval. In our view, in order to be approved by Congress, the bill will likely contain changes to limit the adverse macroeconomic effects noted by the central bank and the government.

GDP is on track to grow 12% in 2021. On Tuesday, November 2, the central bank (BCCh) released September’s Imacec (leading economic activity index), which grew 15.6% y/y. The y/y growth in September was largely explained by services, mainly education and health, followed by trade and manufacturing. Business services, restaurants and hotels and transportation also contributed, consistent with the economic reopening initiated in September. With this, according to preliminary data from BCCh, GDP expanded 17.6% y/y in Q3-2021, the second highest in the last 25 years.

In our view, it will be difficult to maintain the robust growth observed since May 2021 into 2022, given the higher comparison bases and less momentum from private consumption. Even so, we expect GDP to expand 4.5% in 2022, which is explained by a good handoff from 2021, an increase in investment, high level of household liquidity which will support the private consumption, and the possibility of adding USD 11 bn in liquidity pending approval of the latest withdrawal of pension funds. On the negative side, political uncertainty will remain high, while the external sector will provide less of an impulse to growth.

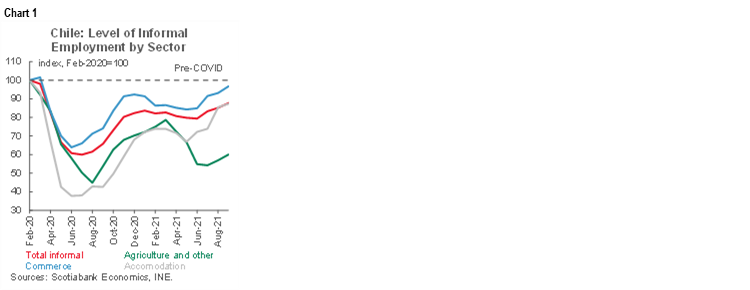

Regarding the labour market, on Friday October 29, the INE released the unemployment rate for the quarter that ended in September, which fell to 8.4%. The decline is explained by the higher growth in employment (1.0% m/m) compared to that of the labour force (0.9% m/m). We observe that the people are continuing to seek employment in a context of high labour demand. With this, the economy has recovered almost 1.3 million jobs compared to the 2 million that were lost as a result of the pandemic. In other words, the gap has now narrowed to 718 thousand jobs still to be recovered, of which 395,000 correspond to formal jobs. Currently, the government is subsidizing the hiring of formal employees, and the goal is the creation of 500,000 new formal positions between August and December, when the program will end. In contrast, the informal employment gap compared to pre-pandemic levels has decreased to 323,000 jobs, of which 118,000 corresponds to agriculture, livestock, forestry and fishing sectors, which could be associated with seasonality factors. In some sectors more associated with the reopening process, like commerce or accommodation services, the gap is around 20,000 jobs in each (chart 1).

In a context of higher inflation figures, the BCCh increased the policy rate in its October meeting, to 2.75%. In addition, on Thursday, October 28, the BCCh released the Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting held on October 13, in which it evaluated an additional hike in the policy rate of between 75 and 150 bps and expressed concerns regarding inflation expectations. The Board members agreed it is necessary to bring the rate closer to its neutral level earlier than anticipated, which in our view would imply increasing the rate to 3.5%–4.0% at the next meeting, to be held on December 14. Our call is for a 125 bps hike, to 4.0%. However, if the fourth withdrawal of pension funds is approved by Congress before the December meeting of the BCCh, we estimate that the Board would evaluate raising the policy rate even beyond 4.0%.

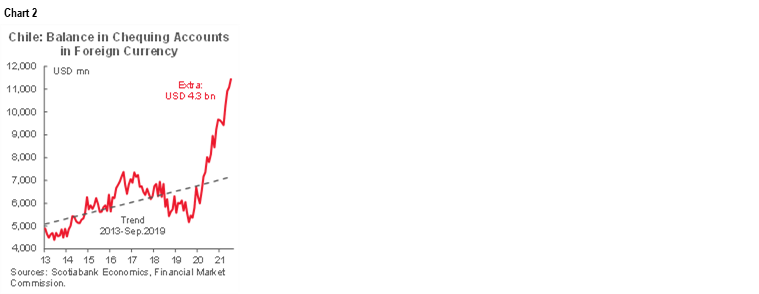

On Wednesday, November 3, the BCCh presented its quarterly Financial Stability Report. The central bank noted a significant negative impact on asset prices stemming from the deterioration of public finances, increased uncertainty and pension fund withdrawals, which have been reflected in falls in stock values, depreciation of the CLP and an increase in long-term interest rates beyond what is observed in international markets. One consequence could be a deterioration of financial conditions in the real estate sector, where mortgage loan rates have increased, as well as the terms and financial requirements for households to acquire a property. According to the Report, new withdrawals from pension funds are the main risk for financial stability. Also, the central bank reports a greater preference for assets in dollars by non-financial companies and households. There is increased purchases of USD by fund managers and companies, as well as an increase in the balances of chequing accounts denominated in USD (chart 2), reflecting an incipient dollarization.

Lastly, in the lead-up to the November’s presidential election, the October 31 Cadem poll showed that the far-right candidate José Antonio Kast continues to lead the race, followed by the left-wing candidate Gabriel Boric. In our view, the survey reflects a reordering within the political forces of the left and right. For now, according to the Cadem poll, Boric remains the strongest candidate in a runoff against either Sichel, Provoste or Kast.

In the fortnight ahead, on Monday November 8, the INE will release October’s CPI. In addition, on Thursday, November 18, the BCCh will publish the GDP growth for the third quarter of 2021.

Colombia—The New Approach of BanRep’s Hiking Cycle

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Faster economic recovery and higher than expected inflation are the two common factors in the global economy this year. It is logical, therefore, that central banks with inflation-targeting frameworks have started, or are about to start, unwinding the significant monetary stimulus provided over the past year to limit the economic and financial effects of the pandemic. However, since the pace of recovery and the resurgence of inflation have been unequal, the question is not if central banks must normalize their policy rates, but what is the optimal path and speed of normalization and level of the terminal rate. And since every country has its own idiosyncrasies, it is important to examine the country-specific factors and the central bank’s unique approach to try to anticipate how the hiking cycle will unfold. Colombia is not an exception here.

There are several challenges to this assessment. First of all, economic activity recovery in Colombia has been hard to follow owing to the nationwide strike in the first half of 2021. The strike not only stopped the recovery in Q1-2021, but also created uncertainty with respect to the political environment, which is unusual for Colombia after a long succession of pro-market governments. In addition, Q2-2021 coincided with the worst wave of COVID-19, which led the central bank to adopt a cautious stance and delay the start of the hiking cycle, given that inflation remained comfortably within the target range. However, after the nationwide strike effects ended in June and the government took an aggressive approach to reopening the economy, economic activity rebounded and in two months recovered what was lost in Q2. In fact, the BanRep’s staff projections for August GDP went from 7.5% in July to 9.8% in October. However, price pressures are a growing source of concern, as core inflation is now expected to surpass 3% next year. In fact, with the unusual volatility of economic activity projections and inflation that has accelerated sharply, BanRep’s staff has changed tack, going from a very gradual hiking cycle to a more aggressive approach. According to the most recent staff forecast, this abrupt shift implies that the neutral rate will be achieved earlier than expected, since negative output gap now is expected to close by June 2022 (only four months ago the output gap was anticipated to close by 2024) (chart 1), while end-2021 inflation is projected to be close to 5%, with end-2022 inflation at 3.6%.

Meanwhile, in recent communications, the most hawkish members of the Board (Steiner and Villamizar) stressed that it is preferable to start the hiking cycle with a more aggressive approach to anchor inflation expectations and ensure that the terminal rate is close to the base case scenario. And since the latest outlook entails a healthier economy with temporary but longer-lasting inflation pressures, in our view, the hawkish perspective underlies the new base case scenario. In this regard, after a gradual hiking cycle started in September (+25 bps), the Board has decided to accelerate its rate hikes and in October increased the policy rate by 50 bps to 2.5% which should be followed by a further 50 bps hike in the December 17 meeting to end 2021 at 3%. For 2022, we think BanRep’s base case scenario is to achieve a neutral rate of 5% by year-end in a 25 bps path approach (chart 2); having anchored inflation expectations by a front-end loaded approach, headline inflation will start to go down and enter the target range by July 2022.

Finally, another reason to initially speed up normalization of the policy rate is that current account deficit financing this year has been mainly with portfolio investment (60% up to June 2021) due to the higher yield in public debt. Thus, avoiding offshore outflows in the short run is one of the things that BanRep is trying to do to ensure the higher current account deficit (-5.3% of GDP for 2021) is well-financed.

Mexico—Labour Market Recovery has Made Progress, but a Gap Remains

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

The Mexican labour market suffered a severe shock at the start of the pandemic, with the labour gap (the sum of unemployment, underemployment, and those available to work) more than doubling as a share of the economically active population in April 2020 (chart 1). The reopening of the manufacturing sector in June of that same year helped recoup about half of those losses, but since then the recovery has lost some steam. While we think there are several factors behind the slow labour market recovery, in our view, weak investment is the main culprit (investment as a share of GDP has fallen about 15-20% over the past 3 years). Rising costs have also affected the recovery, with the outsourcing bill, which limits the use of outsourcing and raising production costs, being the latest shock to hit the economy in August-September 2021, with a sharp decline in the number of employers (chart 2) clearly evident in September (though part of the decline reflects methodological issues).

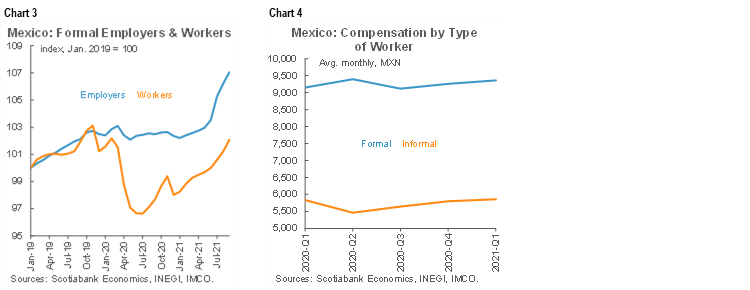

In terms of the recovery dynamics, the data is mixed. We’ve seen a large increase in the number of self-employed workers, likely partly driving the recovery in informal workers in the economy. The formal sector has likewise rebounded (chart 3). By sector, tourism and entertainment-related services continue to lag, as they have done on activity indicators. Our take is that the September setback is only temporary and should be reversed in October-November. It is also noteworthy that average monthly incomes for both formal and informal workers have recovered to pre-crisis levels, at least in nominal terms (chart 4). However, given the current spike in inflation, nominal wages will have to rise faster for real wage gains to recover.

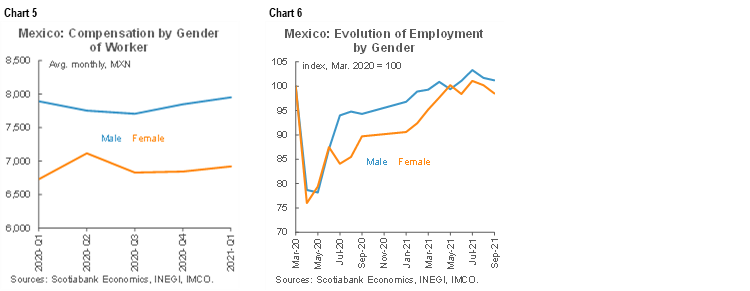

One of the most concerning elements of the Mexican labour market’s recovery has been the lag in the recovery of female employment, both in terms of jobs and income. There has been a clear divergence in wages by gender (chart 5)—a trend that is also being observed in other parts of the world. In terms of jobs, meanwhile, the initial hit taken by male and female employment at the start of the crisis was similar in both strength and pace (chart 6). However, since the June-2020 reopening of the manufacturing sector, which led to the sharp recovery in the labour market, the gap between jobs recovery by gender, which shut in the early months of 2021, has shown a very sharp divergence and has once again widened.

Overall, the recovery of the labour market has been uneven by gender and has at times slowed. The reasons behind this performance are varied, but include continued weak investment, policy decisions that have discouraged job creation, such as the elimination of the outsourcing regime in the summer of 2021, as well as the widely discussed global supply chain disruptions. That said, we anticipate the next leg of the labour market recovery will be driven by a rebound in tourism and entertainment-related services, which could gain traction as soon as Q4-2021, supported by the reduction in border restrictions between the USMCA partners.

Peru—Employment Recovers but with Lower Quality Jobs

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Pablo Nano, Deputy Head of Economic Research

+51.1.211.6000 Ext. 16556 (Peru)

pablo.nano@scotiabank.com.pe

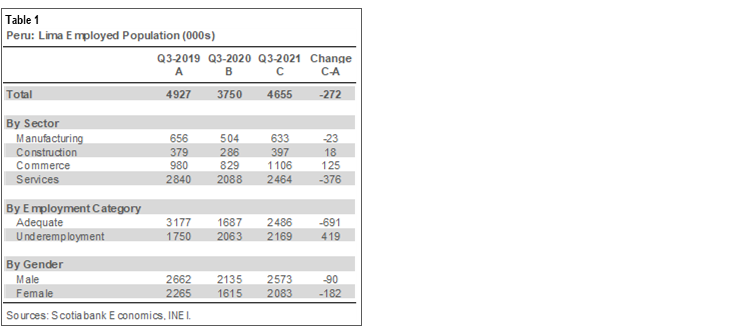

Employment in Lima has continued to recover in recent months (table 1) in the wake of the 2020 COVID-19 lock-down. The recovery has been broadly in line with the rebound in economic activity observed so far in 2021. However, the improvement in the job market has been uneven.

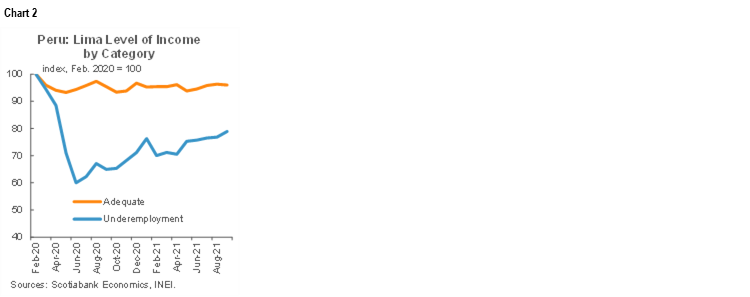

On the one hand, the number of people with adequate employment (i.e., those who work 35 or more hours a week and receive income above the minimum wage) remains below its pre-COVID-19 levels, while the number of under-employed people has increased notably and currently surpasses 2019 levels.

On the other hand, the unemployment rate in Lima stood at 10.0% in Q3-2021, well below the peak of 16.5% registered in Q3-2020 but higher than the 5.8% level recorded in Q3-2019 (chart 1). Unemployment figures must be interpreted with care, however, as informal employment represents around 78% of total jobs and the unemployment rate is thus not a good indicator of the strength of the labour market. The focus, rather, should be on the evolution of under-employment.

At the same time, income levels have not returned to their pre-COVID-19 levels (chart 2). Here, too, the job market has been uneven, as the income of workers with adequate employment has fallen only by about 5%, while incomes of under-employed workers have fallen by around 20%. The reason for this result is that, in the formal labour market, adjustments occur more through the loss of jobs than by a lower income stream.

We expect the recovery in employment to continue in Q4-2021, but do not anticipate a return to Q4-2019 levels over the near term. Note that in the last quarter of the year there is a seasonal increase in employment due to the Christmas season, which translates into an increase in the supply of jobs in commerce and services, two of the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic.

Job market prospects in 2022 are more uncertain. In part, this is because we expect political uncertainty to deter private investment—the main long-term driver of job growth. This could be offset, however, by progress made in the vaccination campaign. The government currently expects 70% of the target population to be vaccinated by Q1-2022. This would allow the restrictions associated with COVID-19 to be further relaxed, improving the outlook for a stronger recovery of service sector jobs. In addition, agro-industrial businesses have remained strong, and this could provide support for jobs growth outside of Lima. Finally, government-sponsored temporary employment programs to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on jobs, including Trabaja Perú, are to continue into 2022. On balance, while unemployment should gradually improve, we expect unemployment to average 8.8% in 2022. While representing an improvement from current levels, this would remain above pre-COVID-19 levels of under 7%.

One final issue to consider is the legislation and labour policies promoted by the Castillo Government. The government has introduced a set of guidelines for its labour policy, called Agenda 19, that could affect labour market dynamics. The Agenda 19 proposals promote labour unions, make it more difficult for workers to be fired, give workers greater collective bargaining powers, among other provisions. The intention is to improve labour conditions. But the risk is that it will deter hiring in the formal sector and enhance labour informality. Agenda 19 is still only a guideline document, and future labour market conditions will depend on the changes that are eventually introduced.

On a complementary note, we are tweaking upward our forecast for the BCRP reference rate for 2022 from 3.50% to 4.0%. Our forecast for end-2021 remains at 2.50%, with a 50 bps increase in November, and another 50 bps increase in December. Julio Velarde was sworn in as President of the Board of the BCRP for the 2021–2026 period. At the same time, with inflation at 5.8% and on its way to our forecast of 6.5% by year end, it is becoming more of an issue than growth. Moreover, we expect inflation to surpass 7% in early 2022, which would add urgency to central bank action. This, and an environment in which emerging market central banks are increasing their reference rates at an accelerating pace, make us more inclined to believe that the BCRP will also be more aggressive. In this respect, it is noteworthy that the BCRP surprised us last week when it raised its reserve requirements on bank deposits for a second time in recent months.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.