This is our last Latam Weekly of 2020; the next edition is scheduled to be released on or about January 23, 2021. Our other Scotiabank Economics Latam reports will continue to be published up to and including Friday, December 18, at which point a brief three-week hiatus will begin. Our first Latam Daily of 2021 will land in your inboxes on Monday, January 11, to kick off the new year.

Best wishes for very happy and safe holidays from all of us at Scotiabank Economics!

FORECAST UPDATES

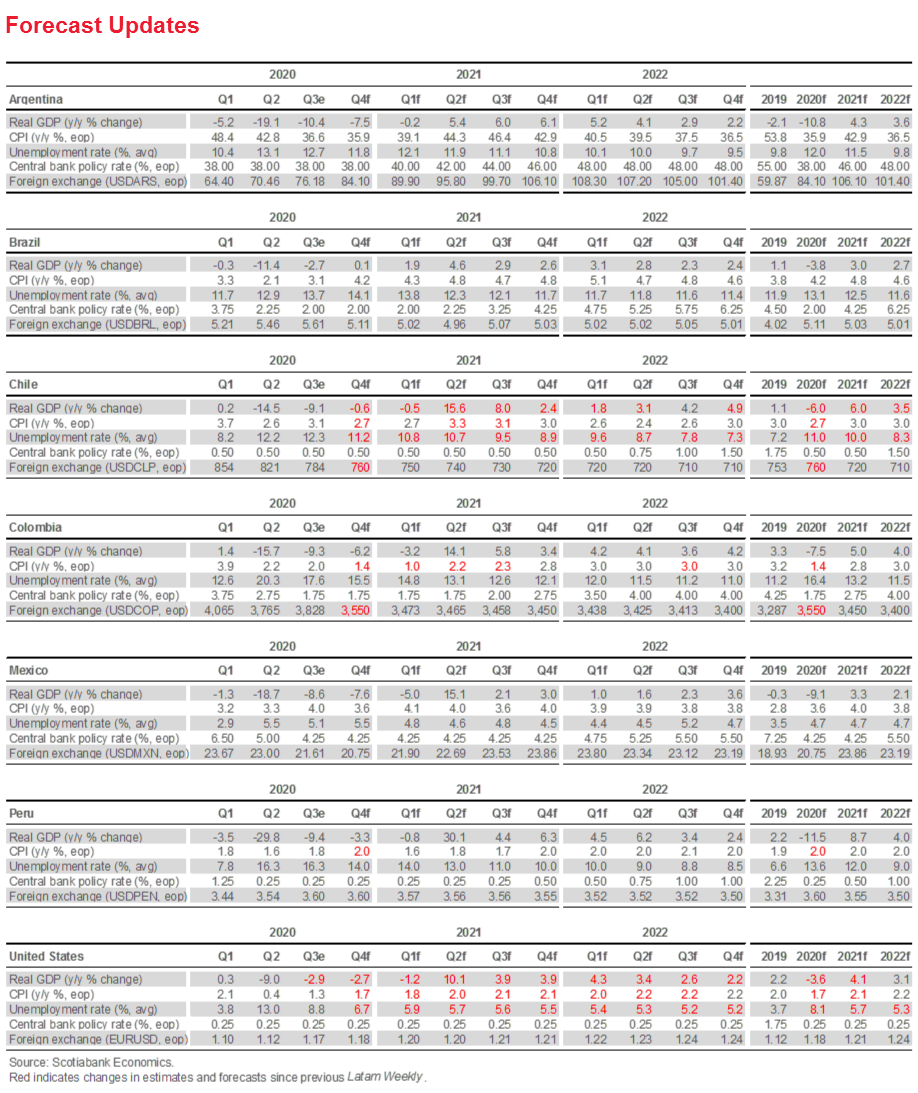

Our revisions square up our end-2020 inflation projections in Chile and Colombia, and our 2020 real GDP growth numbers in Chile, with recent data releases. Otherwise, we reaffirm our outlook for our two-year forecast horizon as second waves of COVID-19 roll onward and vaccine distribution begins.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

As 2020 comes to a close, we take stock of the year ending and point to some familiar macro themes for 2021 in Latin America.

COUNTRY UPDATES

We assess key insights from 2020 and highlight the main issues to watch in 2021 at the national level in the Latam-6: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

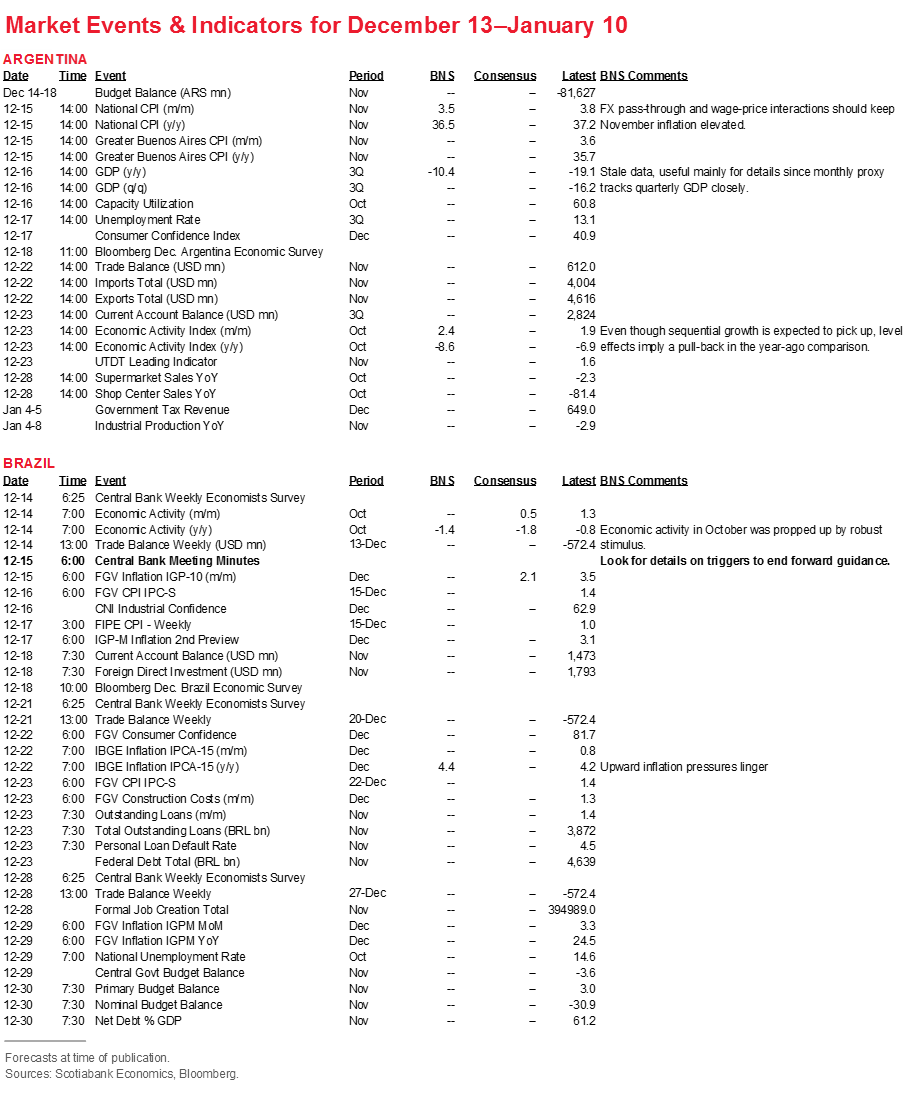

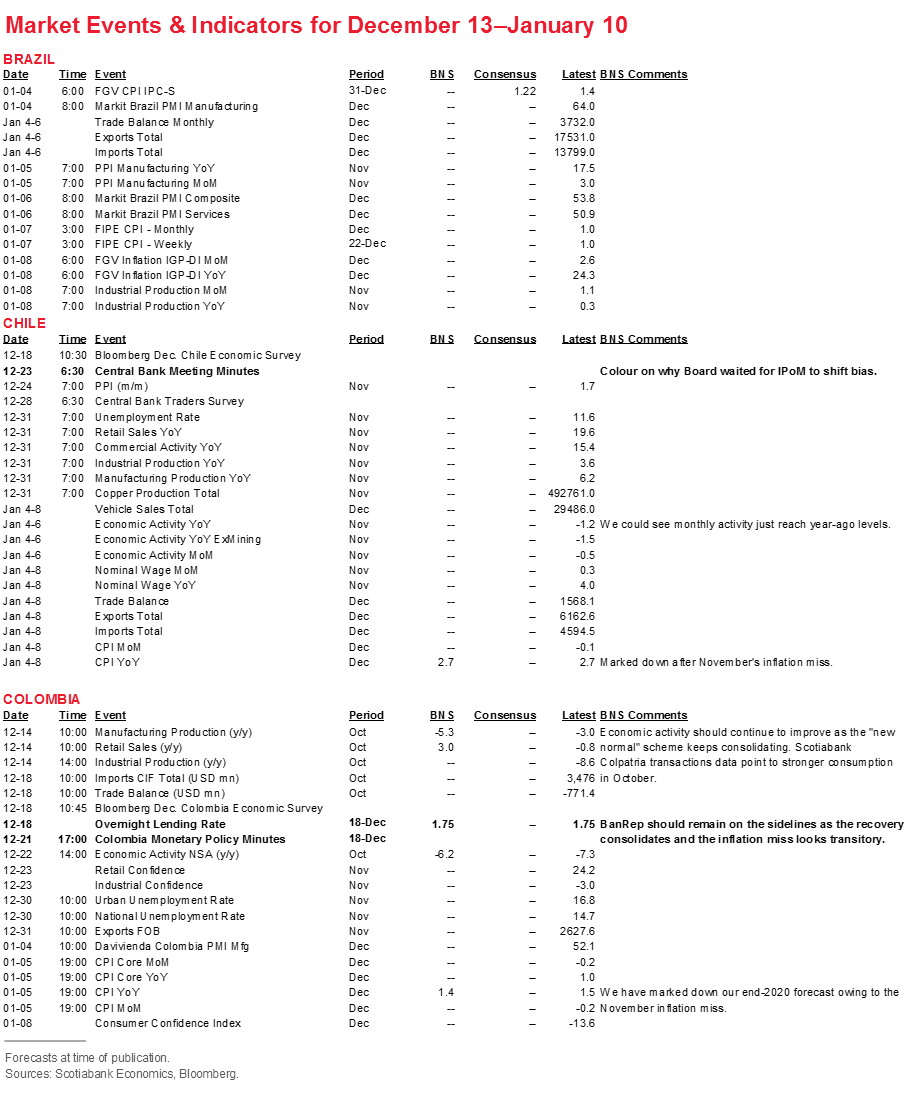

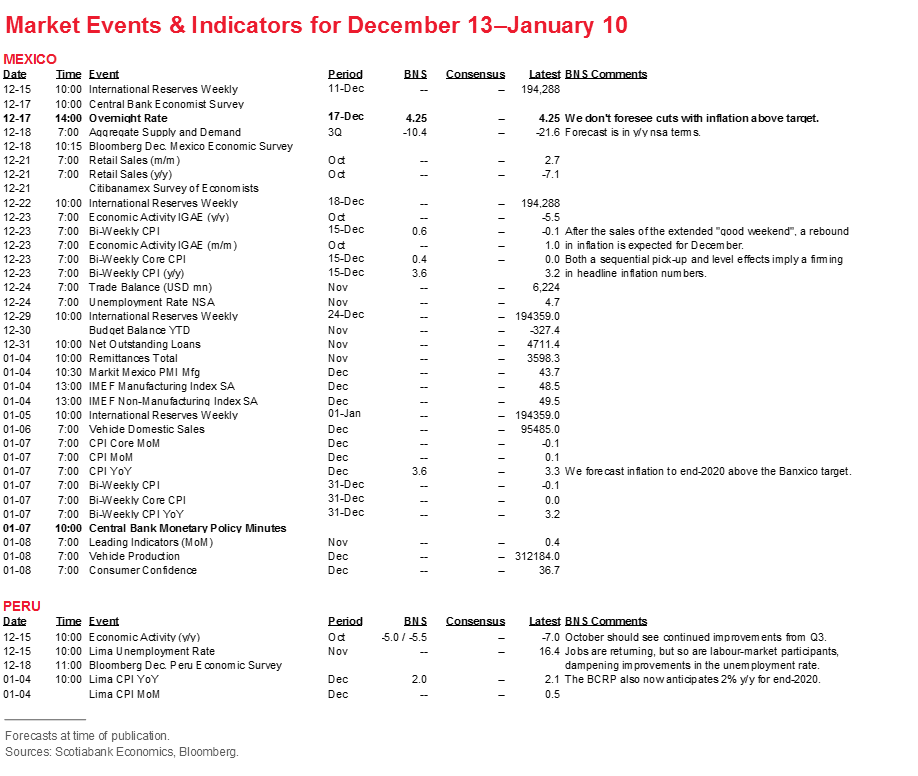

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

Risk calendar with selected highlights for the period December 13–January 10 across our six major Latam economies.

Economic Overview: New Year, Familiar Issues

Brett House, VP & Deputy Chief Economist

416.863.7463

Scotiabank Economics

brett.house@scotiabank.com

Growth rebounds, low inflation, accommodative policy rates, gradual fiscal consolidations, and moderate FX appreciations are likely to be the economic hallmarks of 2021 in Latam. Political developments will remain important risk determinants across the Latam-6 as capital continues to flow back into the region.

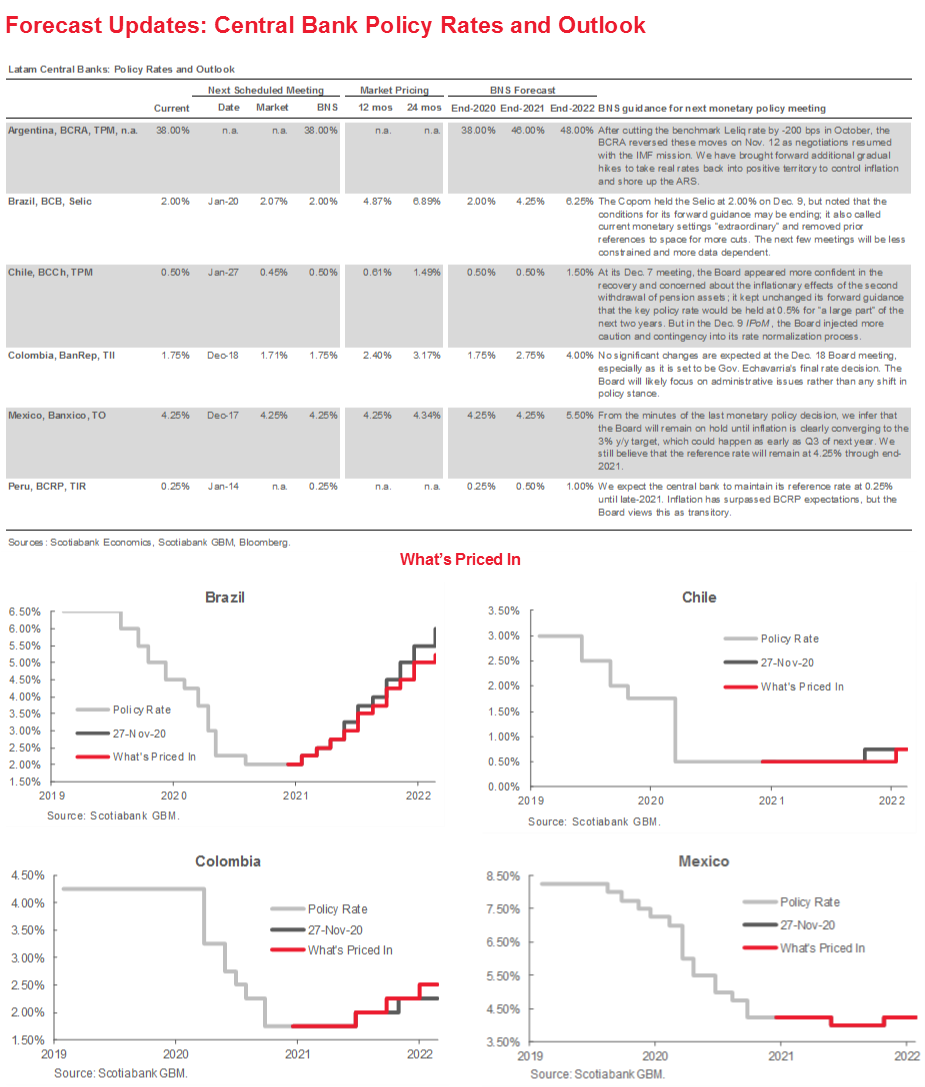

The final monetary-policy decisions of 2020 are due this week from Mexico’s Banxico (Dec. 17) and Colombia’s BanRep (Dec. 18), with minutes from Brazil’s BCB (Dec. 15), followed by its quarterly Inflation Report. (Dec. 17).

FORECAST UPDATES & COVID-19 DEVELOPMENTS

Our forecast revisions are focused this week on squaring up numbers for end-2020 and reaffirming our outlook over the two-year forecast horizon as second waves of COVID-19 roll onward in many parts of the world and vaccine distribution begins. Following downside inflation surprises in November, we sliced our end-2020 headline forecasts in Chile and Colombia, but kept our projections for the next two years broadly unchanged. Similarly, in line with the BCCh, we deepened our expected contraction in Chile’s real GDP in 2020 after the October monthly GDP proxy disappointed, with a compensating additional boost to 2021’s rebound owing to the second round of pension withdrawals.

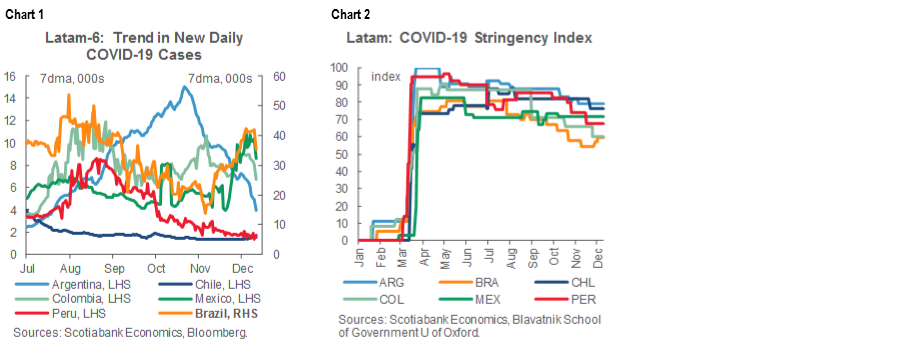

After several weeks in which Latam’s COVID-19 hotspot has been cooling at the margin, new infection numbers are again worryingly high in several parts of the region (chart 1). The seven-day moving average of daily new positive tests remains elevated in Brazil and Mexico, while Colombia remains range-bound at the moderate numbers at which it has been stuck for months. Although new infection numbers in Chile and Peru are still low, they are no longer declining and appear to be backing up slightly. Argentina is the only country in the region that continues to see a sustained decline in new case numbers, albeit from very high levels from a few months ago. Chile recently imposed new restrictions in the Santiago area to head off a new upswell in infections, and more widespread intensification of contagion control measures going into the holidays could dampen the economic hand-off into 2021 (chart 2).

THEMES FOR 2021

Growth rebounds, low inflation, accommodative policy rates, gradual fiscal consolidations, and moderate FX appreciations are likely to be the economic hallmarks of 2021 in Latam. Political developments will remain important risk determinants across the Latam-6 as capital continues to flow back into the region.

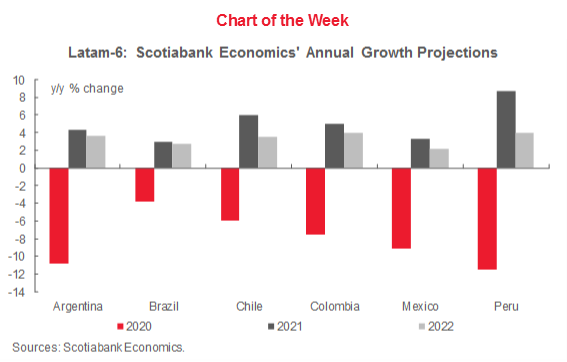

- Growth. The 2021 recovery will favour countries that have acted to control the virus and support their households and businesses. After Q2-2020’s lockdowns and the initiation of re-openings in Q3, we project an average contraction of -8.1% y/y across the Latam-6 in 2020, with the deepest losses in Argentina and Peru (chart 3). Growth in 2021 is forecast to rebound to an average of 5.1% y/y in the region, led by Peru and Chile—the two countries amongst the Latam-6 that have maintained the strictest contagion-control measures for the longest periods of time, and the two countries that have implemented the largest fiscal and financial support packages in terms of their share of GDP. By both quarterly and annual measures, Chile is set to lead the region in returning to 2019 levels of economic activity, with Brazil close on its heals (charts 4 and 5). Our forecasts assume vaccine distribution moves to scale around mid-2021 across Latin America. At the sectoral level, retail and manufacturing are likely to lead economy-wide growth, while employment will lag the recovery as relatively labour-intensive service sectors take longer to re-open, as we outlined in our November 28 Latam Weekly.

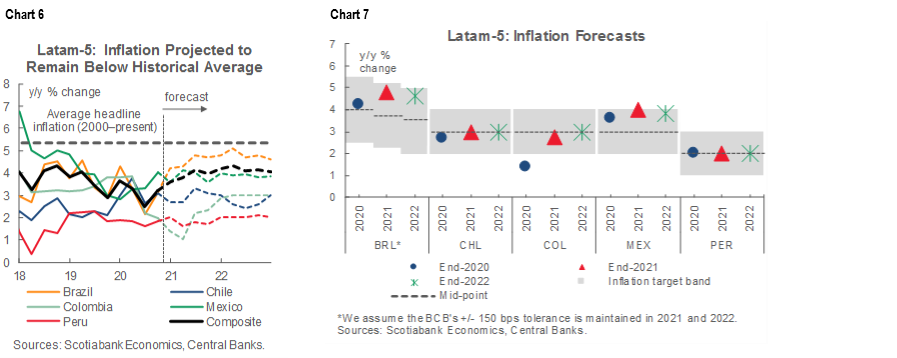

- Prices. Inflation is set to remain muted in 2021. We project headline inflation to average 2.8% y/y at end-2020 across the Latam-5 inflation-targeting regimes (i.e., ex Argentina), and accelerate only mildly to an average of 3.3% y/y by end-2021 and stay there at end-2022 (chart 6). This implies that headline inflation in the Latam-5 will, on average, remain about 150 to 200 bps below the region’s trend since 2000. Still, we expect inflation in Brazil and Mexico to remain persistently in the top half of their target bands over our two-year forecast horizon (chart 7).

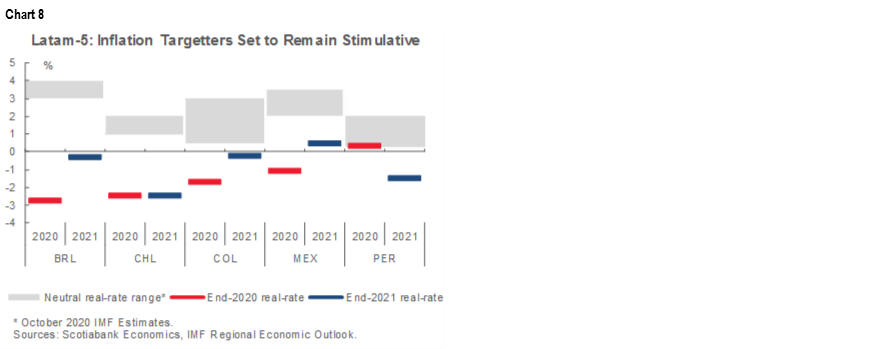

- Monetary policy. Interest rates are expected to remain accommodative. Even though nominal rates are expected to begin lifting off as soon as Q2-2021 in Brazil (see the Forecast Updates table on p. 2), ex-ante real rates are forecast to remain well below their neutral levels through end-2022, which should help sustain recoveries across the Latam-5 inflation targetters (chart 8). Ex-ante real rates in Argentina are currently in negative territory, but are expected to turn positive as nominal rate hikes are implemented in 2021 to bring inflation under control (see the Argentina Country Update section).

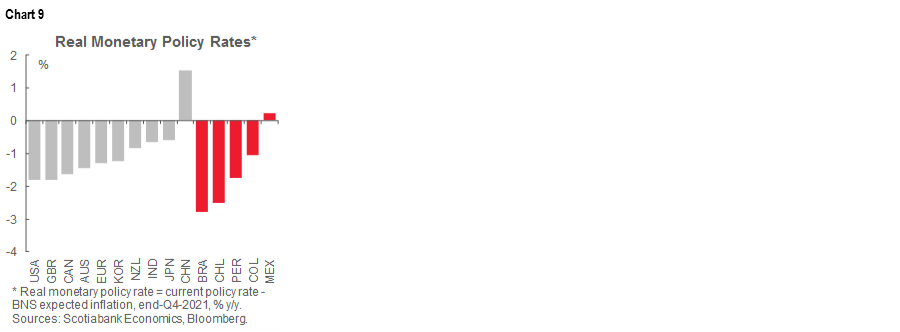

- External sector. Capital reflows may lag those into other emerging markets. After massive outflows in Q2, most emerging markets are now seeing solid portfolio inflows as global risk sentiment improves and investors renew the search for yield. With some of the most deeply negative real rates compared with other major markets (chart 9), domestic debt markets in Latin America may lag those in other EMs until the region’s rate-normalization process proceeds further. After the region’s currencies acted as substantial shock absorbers during 2020 and were some of the worst performers across the EM FX complex, we anticipate gradual appreciations, with the ARS and MXN standing out as exceptions.

- Fiscal policy. Fiscal consolidations are expected across the region. Governments across the Latam-6 will begin to withdraw the exceptional fiscal support they provided their economies this year, but the paces by which they do so will remain varied and contingent on progress in containing the pandemic. Argentina is expected to cut its primary deficit nearly in half in order to reach an agreement with the IMF on new financing, while Brazil and Colombia are due to undertake substantial structural reforms. Given the huge COVID-19 responses launched in Chile and Peru in 2020, both will likely maintain primary deficits in 2021 that will be well above their pre-pandemic levels. Only Mexico will avoid a big fiscal pullback owing to the small size (0.7% of GDP) of the its COVID-19 support package.

- Politics. Political risk will remain an important factor in 2021. With a process to write a new constitution beginning in Chile, presidential elections in Peru, mid-term elections in Argentina and Mexico, new speakers set to be named for both of Brazil’s legislative chambers, and jockeying beginning for Colombia’s 2022 presidential vote, politics and economics will be tightly intertwined in the year ahead. Negotiations between the IMF and Argentina are likely to be as fraught as ever.

CENTRAL BANKS EXPECTED TO CLOSE OUT 2020 WITH MORE HOLDS

The final monetary-policy decisions of 2020 are due this week from Mexico’s Banxico (Dec. 17) and Colombia’s BanRep (Dec. 18), with minutes from Brazil’s BCB (Dec. 15), followed by its quarterly Inflation Report. (Dec. 17).

- Brazil. The BCB is scheduled on Tuesday, December 15, to publish the minutes from its Copom meeting on Wednesday, December 9, where the Committee voted unanimously to keep the Selic rate unchanged at 2.00% for a fourth time in a row. The Copom’s statement tweaked its forward guidance with a more hawkish bent, in our view, as it noted that “the conditions for maintaining the forward guidance may soon no longer apply”. We’ll look to the minutes for additional details and colour on the possible triggers that could lead to the withdrawal of the Copom’s guidelines on its future rate-setting behaviour, particularly as the BCB’s inflation target is set to step down from 4.00% y/y in 2020 to 3.75% y/y in 2021 and 3.50% y/y in 2022 (chart 7, again).

The BCB’s December Inflation Report is due to follow on Thursday, December 17, and deliver revised macroeconomic forecasts. The new projections should provide an important gut-check on our outlook that sees the Copom beginning its rate normalization process in Q2-2022.

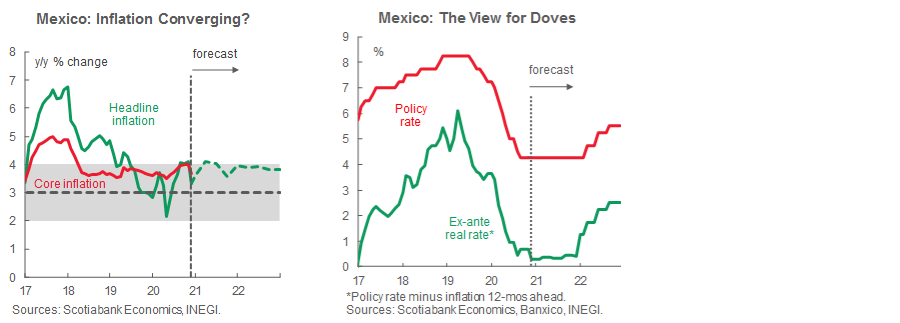

- Mexico. The last scheduled monetary-policy meeting by Banixco’s Board is planned for Thursday, December 17, where our team in CDMX expects the central bank to keep its benchmark policy rate on hold at 4.25% (see charts in the Mexico Country Update section). In a split 4-1 decision to hold on Thursday, November 12, one member opted for a cut to 4.00% and the statement and subsequent minutes noted that the hold should be seen as a “pause” for the Board to confirm that inflation is indeed converging over time to its 3% y/y target. We believe that the Board’s hawks will look through November’s downside inflation surprise and October’s contraction in credit to the private sector and keep a majority of the Board behind a hold this week. We forecast an increase in annual inflation rates back to the upper limit of the target range in 2021 (see Forecast Update on p. 2 , chart 7 again, and the charts in the Mexico Country Update section). We continue to see Banxico on hold until early-2022.

The minutes of the meeting are scheduled for publication on Thursday, January 7.

- Colombia. In the last major Latam central-bank risk event for 2020, the BanRep Board will meet on Friday, December 18, and our economists in Bogota expect the headline policy rate to be held at 1.75% at the end of a relatively quiet discussion focused on administrative issues (see charts in the Country Update section). The meeting will be Gov. Echavarria’s last scheduled rate-setting decision before leaving office on January 3, 2021, and in this context, no major changes are anticipated before his successor, Leonardo Villar, takes over on January 4.

At the BanRep Board’s previous monetary-policy meeting on Friday, November 27, members voted unanimously to keep the policy rate at 1.75% for a third month and issued an unusually short statement that, in our assessment, simply reiterated their data-dependent, open stance. The minutes of the meeting, which followed on Monday, November 30, doubled down on the Board’s concerns about the labour market, but lightened worries about second waves of COVID-19. Although November inflation surprised on the downside and led to a revision in our end-2020 projection from 1.8% y/y to 1.4% y/y, with level effects expected to keep headline annual inflation low in early-2021, continued re-opening of economic activities next year should have prices tracking back toward the BanRep’s target by mid-2021 without necessitating any further easing (chart 7, again). We expect the BanRep Board to remain on hold until Q3-2022, though changes to the Board next year (i.e., possibly two new members in addition to the Governor) could shift the balance of hawks and doves.

The minutes from the Friday, December 18, meeting are due to be published on Monday, December 21, under the BanRep’s usual calendar.

- Chile. The BCCh shall publish the minutes from its Monday, December 7, meeting where it held its key monetary policy rate unchanged at its 0.5% technical minimum on Wednesday, December 23. In its December 7 statement, we thought the BCCh Board sounded more confident on the recovery and the inflationary effects of pension withdrawals, but in the December Monetary Policy Report, the Bank struck a more dovish note. We’ll look to the minutes for more insight on why the Board deferred the shift in its bias to the IPoM.

MACRO DATA

See our risk calendar at the back of this report for a full set of events and our forecasts for the most important developments expected between now and Sunday, January 10. Tomorrow’s Latam Daily will highlight key data releases in the week ahead.

USEFUL REFERENCES

Google, “Year in Search 2020”, December 10, 2020: https://about.google/stories/year-in-search-2020/

New York Times, “2020 in Photos: A Year Like No Other”, December 9, 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/year-in-pictures.html

COUNTRY UPDATES

Argentina—Inflation Remains the Watchword for 2021

Brett House, VP & Deputy Chief Economist

416.863.7463

brett.house@scotiabank.com

Argentina’s post-lockdown recovery is expected to roll into 2021, aided by the arrival of vaccines against COVID-19 and improved global resource demand. Nevertheless, policy and political considerations complicate the outlook for next year as the authorities look to complete negotiations with the IMF on a new borrowing program ahead of mid-term elections in October that could widen fissures in the ruling Frente de Todos coalition. Still-elevated inflation rates and the country’s dual currency markets are likely to remain both significant challenges and barometers of the authorities’ efforts to undertake structural adjustment, that old bugbear of Argentine populists.

Argentina’s H2-2020 recovery should continue into 2021 and break three years of recession, but still leave the economy just above levels of activity last seen just under a decade ago. After a pandemic-induced contraction projected to hit -10.8% y/y in 2020, we expect real GDP to grow by 4.3% y/y in 2021 and 3.6% y/y in 2022 (see the Forecast Updates table on p. 2). Our outlook anticipates the arrival and initial distribution of COVID-19 vaccines in Q2-2021, followed by substantial easing of the country’s extended lockdown measures. Still, consumption is expected to recover only gradually as fiscal support is pulled back and hard-hit, labour-intensive service sectors re-open behind the rest of the economy. This means that Argentina’s formal unemployment rate is forecast to stay in the double digits until end-2022. Although the authorities intend to increase public investment over the coming years, it is likely that capital spending’s broader economic impact will be offset to some extent by more constrained growth in current public spending. Relatively soft domestic demand for imports amidst a strengthening bid for Argentine agricultural and resource exports should sustain solid trade surpluses and a current account in the black through 2021.

Inflation is set to remain a persistent concern. Although level effects from 2019’s price pressures should bring headline annual inflation down to around 36% y/y by end-2020, sequential monthly inflation accelerated over the last few months to 3.8% m/m in November. We expect monthly inflation to average above 3% m/m through Q3-2021 and bring the annual inflation rate back to about 43% y/y by end-2021 owing to some easing in price controls, the ongoing monetization of fiscal deficits by the BCRA, and pass-through effects stemming from further depreciation in the official ARS (first chart) amidst un-anchored inflation expectations (second chart). Inflation will be even higher in 2021 if the unification of the exchange market leads to a faster depreciation—or stepwise devaluation—of the official peso than laid out in our forecast. Under an assumption that an adjustment program is agreed next year in the context of a new IMF lending arrangement, we project sequential monthly inflation to come back down toward 2% m/m in 2022 and close the forecast horizon around 37% y/y. With ex ante real interest rates still in negative territory (third chart), we expect the BCRA to raise its rate complex by 800 bps over the course of 2021 to curb inflation, rein in expectations, and shore up the ARS, with another 200 bps of hikes in early-2022.

For monetary restraint to be effective—or even possible—it will have to be accompanied by a suite of fiscal adjustments whose delivery remains uncertain. With a primary deficit set to go wide of -8% of GDP in 2020, there will be ample room to rein back spending in 2021 and reduce Treasury draws on the central bank. Although some reduction in current government expenditure is likely, we don’t expect it to bring the primary deficit below -5% of GDP in light of the IMF’s recent change in tune on fiscal austerity, the potential hit to growth that deeper cuts would imply, government promises to keep benefits, pensions, and wage growth ahead of inflation, and the looming mid-term elections in October 2021.

Negotiations with the IMF will be front and centre going into 2021 and inform most major policy decisions reviewed above. We don’t expect talks to conclude until late-Q1 or even early-Q2 on the roll-over of Argentina’s outstanding IMF debt to a new—and larger—arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF).

Brazil—Politics Come to the Fore as Fiscal Consolidation Challenges Rise to the Top

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

A recent ruling by Brazil’s Supreme Court barred the heads of the country’s two legislative chambers from seeking re-election, adding an additional layer of uncertainty to the future of the government’s reform agenda, including fiscal consolidation. The current heads of both houses have been supportive of President Bolsonaro’s reforms and friendly replacements are expected, but this is not a given. In Brazil, the head of each house has the power to schedule legislative votes, so keeping a supportive chair in each chamber is important as they have the authority to speed up, delay, or freeze the passage of bills. In addition, another angle to consider is whether the heads of the houses are part of Bolsonaro’s coalition, or whether they are from a rival political coalition (even if market-friendly themselves). This will become particularly relevant in the latter half of 2021 as jockeying begins ahead of the next presidential elections due in October 2022.

New heads for each house are unlikely to be selected until February 2021, meaning most reform discussions will likely resume in March. As a result, legislation on fiscal consolidation is likely to be delayed and could be altered, depending on the leaders that are elected for each chamber. We do not expect the BCB reform bill to become politicized.

So far, most of the government’s fiscal consolidation agenda seems to be focused on tax reform proposals, which are being presented and discussed in stages (i.e., specific taxes, rather than a comprehensive reform). Our take is that additional tax collection efforts are a temporary stopgap, but raising taxes is not enough to solve the country’s long-term fiscal issues. As we have argued in the past, Brazil already has a relatively high tax burden compared with other economies in the region: Brazil’s government accounts for close to 40% of GDP, whereas in much of the rest of the region, government accounts for 20–30% of GDP.

Brazil’s big government isn’t producing big results. Despite OECD-like levels of government spending/revenues, Brazil scores near the bottom in PISA education achievement, and 71st out of 141 countries in terms of its overall business environment in the World Economic Forum’s rankings (chart), surrounded by countries that generally have lower income levels (India, Vietnam, Georgia, Philippines, etc.). Many of the elements that weigh on this competitiveness ranking are issues related to a bloated and inefficient government and poor infrastructure quality, which imply that Brazil has a large government, but not a particularly effective one compared with regional peers such as Mexico (table). A high tax burden and poor business environment likely explain, at least in part, Brazil’s relatively low investment-to-GDP ratio compared with the rest of Latin America (around 15% of GDP). This affects long-term growth potential, which we now estimate at around 2.0% y/y. Fiscal sustainability is basically determined by potential growth rates, interest rate costs, and debt-to-GDP ratios. With Brazil’s gross general government debt moving north of 100% of GDP this year, it is critical for the authorities to focus on boosting potential growth; we believe that shrinking the size and cost of government will be key. However, additional progress on micro reforms is also important.

Prospects for key economic variables in 2021 are mixed. The strength and speed of the rebound in domestic demand in 2020 was surprising; for instance, retail sales turned positive on a year-on-year basis in June, and by September they were up 7.3% y/y. This was helped by fiscal stimulus north of 4 percentage points of GDP, which is set to expire in January, meaning that domestic demand is likely to soften materially. However, as the year moves on, we could see some lagging sectors—such as those related to entertainment—pick up their levels of activity if, as expected, control of the pandemic progresses. On the inflation front, the bulk of price pressures have come from consumer non-durables (i.e., items such as food, clothing, and transportation), which should moderate with the softening of fiscal stimulus and consumer demand. This could give the BCB some relief, which we expect to be offset by broader price pressures as more of the economy re-opens and the output gap closes. We expect the net result of these two forces to be “more balanced” inflation in 2021.

Chile—Strong Economic Momentum Entering a Politically Complex 2021

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2939.1092 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Carlos Muñoz, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.6848 (Chile)

carlos.munoz@scotiabank.cl

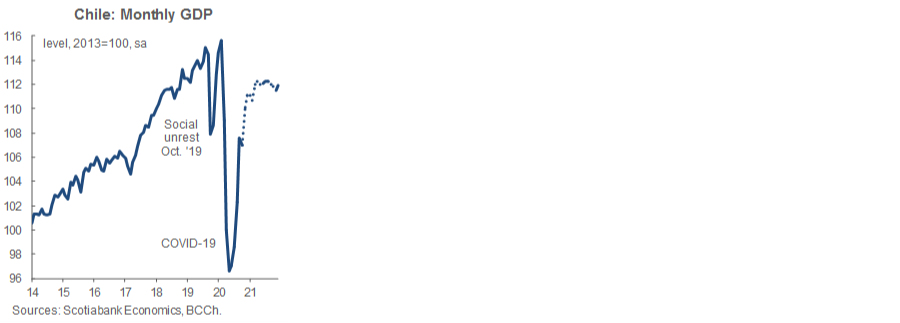

The Chilean economy began 2020 with positive surprises in January and February, after the sharp decline in activity following the social outbreak of October 2019. However, this promising beginning was soon cut short. By mid-March 2020, the whole country entered a strict lockdown as COVID-19 cases started to rise sharply. The referendum on initiating a process toward a possible new constitution, which was one of the demands of the demonstrators, was pushed to October 2020, and the authorities had to implement urgent and massive measures to keep the economy afloat.

The effects of the pandemic were severe: 2 million jobs were lost while economic activity contracted -12.5% y/y in the second quarter of 2020. Nevertheless, there has been heterogeneity in the pandemic’s impact: sectors where close social interaction is required have been hit the hardest, with services linked to tourism, restaurants, and hotels showing sharp declines in activity. Construction has been another sector where activity has plunged. On the other hand, mining, manufacturing, and commerce have weathered the pandemic well, and have returned to pre-COVID-19 levels of activity.

To face the crisis, the government mobilized resources of around USD 29.1 bn (~12% of GDP) to support household incomes and to provide liquidity to firms. Congress approved a first withdrawal of pension assets in July that poured another USD 17.7 bn (~7% of GDP) in liquidity directly into the pockets of contributors. The central bank, for its part, reduced the monetary policy rate to 0.5% (its technical minimum) at end-March and implemented a series of measures to inject liquidity into the financial system.

As 2020 comes to an end, economic data confirm that the recovery is advancing. The third quarter showed an expansion of 5.2% q/q sa and for the fourth quarter we expect growth around 9% q/q sa. With approximately 90% of the economy re-opened, Congress approved in early-December a second withdrawal of pension assets, which should send another USD 16 bn of liquidity to households. In addition, the government is preparing an additional round of fiscal stimulus aimed at boosting both investment and consumption. Disparities in the economic recovery have also been reflected in the labour market. The latest data show that about a third of the jobs lost during the pandemic have been recovered, but gains in employment have been slower in services, which are relatively labour-intensive.

Next year should start with elevated economic momentum coming from strong private consumption growth and an even greater degree of economic re-opening. However, there are still important risks to consider. The economy will face evolving challenges from the pandemic and the political situation that has followed October 2019’s social unrest. The labour market still has wide gaps that are expected to remain open next year in a context where investment has underperformed and the prospects for 2021 are still weak. Full recovery remains a titanic task for the labour market, even more so because of the acceleration in the digitization of work during this year’s lockdowns. With investment still subdued, this challenge is made even harder, and we could see the demand for labour become less intense in the coming quarters. We may even see the unemployment rate edge up as returns to the labour market could outpace jobs gains.

Even though external stimulus has positively surprised in the last few months, pushing the copper price above USD 3.50/lb, and vaccine advances have arrived more quickly than expected, the constitutional process and its subsequent political uncertainty add a note of caution for investment in 2021. Rapid immunization of the population and the maintenance of liquidity measures are necessary to strengthen business and consumer confidence and, thus, foster a solid recovery of investment, which is expected to decline more than -10% y/y in 2020.

On the other hand, in October 2020, Chileans voted “yes” in the referendum for a new constitution, a process that will reach another milestone on April 11, 2021, when the delegates of the Constitutional Assembly will be elected. We expect that the composition of the Assembly shouldn’t be very different from the current make-up of Congress which, combined with the requirement of a two-thirds majority to approve any article, should leave little room for extreme positions to prevail. However, strong debates will occur around sensitive topics such as the guarantee of social rights, particularly health and education; the role of the state in the provision of pensions; the independence and autonomy of the central bank, which we do not see being modified; property rights, especially water rights; minority issues; and the system of government. These public discussions could add some uncertainty to the recovery process even it they don’t result in substantive changes. But 2021’s political events won’t end with the new constitution: there will be presidential and congressional elections in November 2021.

All in all, we are optimistic about the economic recovery and the evolution of the constitutional process during 2021. The Chilean economy has shown resilience following 2019’s social outbreak and the pandemic; additionally, the authorities have provided ample stimulus to support the recovery, which will be maintained as we enter 2021. Along with this, the global economy has recovered faster than expected and we don’t see its momentum waning in 2021, which should foster an appreciation of the CLP. The central bank has maintained the policy rate at its technical minimum and has communicated that it will do whatever is necessary to support the economy, which leads us to forecast the maintenance of the policy rate at 0.5% throughout 2021 and a large part of 2022. Prices should see some upward pressures at the beginning of 2021 stemming from the withdrawal of pension funds, but the economy’s negative output gaps should dampen these effects; we project that headline inflation will end December 2021 at 3.0% y/y. Taking all of this into account, we project that the economy will contract -6% y/y in 2020, with a rebound of 6% y/y in 2021.

Colombia—After the Storm, the Macro Adjustments Arrive

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabank.com.co

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabank.com.co

During 2020, Colombia began to show very positive signs in terms of economic activity. In the first two months of the year, the Colombian economy grew at an annual rate above 4%, the best growth since 2015, supported by a strong external environment backed by solid domestic demand. However, in March, COVID-19 suddenly interrupted the excellent start to the year and plunged the Colombian economy into the worst economic crisis in recent history, in line with the rest of the world. That event resulted in a significant change to policy plans for the country.

At a very early stage of the contagion (i.e, with less than 500 cases), Colombia entered into an extended lockdown on March 25, which produced a contraction of -4.3% y/y in the month’s economic activity as more than 30% of the economy was closed. Lockdown measures produced a record drop in economic activity of almost -16% y/y in Q2-2020 GDP and -9% y/y in Q3-2020. Colombia allowed a gradual resumption of activities from September, leading to the current “new-normal” scheme in which 95% of the economy is now operational.

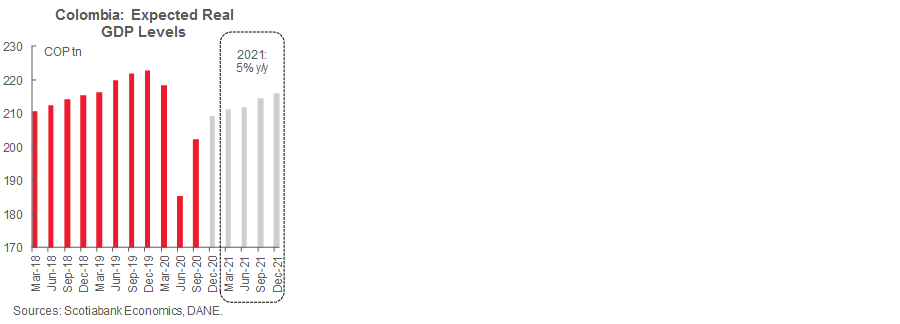

Although it seems that the recovery is gradually consolidating, the COVID-19 shock has made a permanent dent in the Colombian economy. Thus, we estimate that a good part of the -7.5% y/y decline in 2020 GDP has pushed potential output down as well, making the output gap smaller than had been initially expected. If the Colombian government allows the economy to keep working under the mild mobility restrictions in September’s new-normal scheme, we would expect economic growth of 5% y/y in 2021 (first chart). At the same time, public policy will focus on stimulus for labour-intensive sectors such as construction and retail, where physical distancing remains difficult.

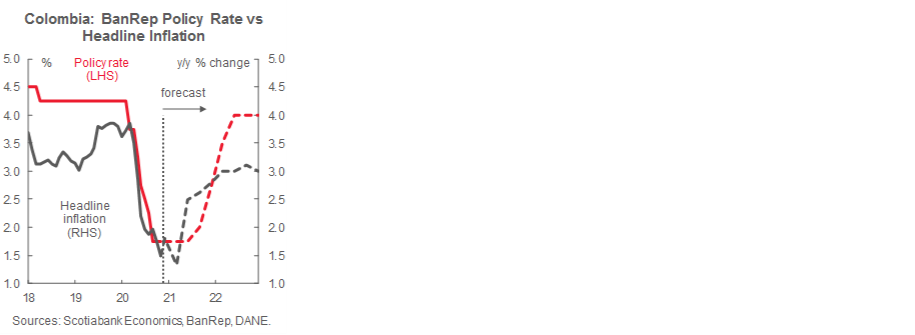

The COVID-19 shock triggered a 180-degree change in monetary and fiscal policy plans. Before the COVID-19 shock, the BanRep was expected to increase its policy rate slightly to a more neutral level of ~5%; however, once the shock kicked in, the central bank gradually eased the policy rate, cutting by -250 bps to a historically low nominal rate of 1.75%, and implementing unconventional measures to guarantee liquidity. For the first time, the BanRep grew its balance sheet by buying public and private debt to avoid issues in credit markets and to ensure that its rate cuts were transmitted to businesses and households: the BanRep bought COP 2 tn of TES and COP 10 tn in private debt.

On the fiscal side, the government suspended the fiscal rule—which had pointed to a reduction in the fiscal deficit to -2.2% of GDP in 2020—and instead implemented a strategy of countercyclical expenditures, which unavoidably and significantly increased its deficit (second chart). Total extra spending is now calculated at 4% of GDP, while tax revenues are expected to contract around -9% versus 2019 as a result of weaker economic activity and a temporary reduction in some taxes. Although this has put Colombia’s credit rating under pressure, the country has remained in the investment-grade (IG) group. Continued IG status is, however, strongly conditional on passing an ambitious tax reform that should increase fiscal income by 2 ppts of GDP. For context, Colombian tax reform packages typically collect just 0.6% of GDP. We expect fiscal discussions to start in Q1-2021 after the government’s committee of experts releases its first report on tax exemptions. It is worth noting that the Ministry of Finance has emphasized that it is considering enlarging the basket of items to which the VAT is applied.

On the external side, we expect a wider current account deficit on the back of higher imports, which usually mirror better investment dynamics, and a smaller recovery in traditional exports— mainly coal and oil—which will face challenges from international demand. However, as global trade improves, better commodity prices and risk appetite will help finance a slightly wider current account deficit of -3.8% of GDP in 2021. Therefore, we do not see upward structural pressures on the COP from the balance of payments perspective. Although we foresee a higher current account deficit, improved external sentiment and low international interest rates should increase the appetite for Colombian assets and lead to larger portfolio inflows. Additionally, better expectations in the real sector should also help FDI to recover and to finance a significant portion of the widening in the current account deficit. Thus, although we think there is room for appreciation of the peso to levels close to USDCOP 3,400 in Q1-2021, tax reform and fiscal consolidation, as well as the beginning of the presidential election campaign, could keep the peso in the USDCOP 3,400–3,550 range during the rest of 2021.

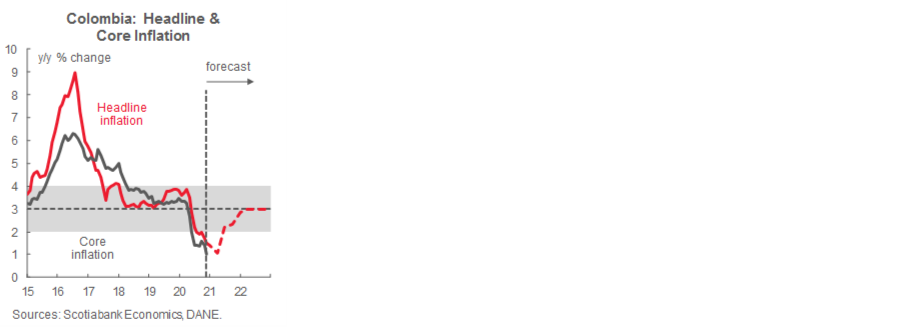

The COVID-19 shock has also had a significant impact on Colombia’s inflation. While Colombia started 2020 with inflation in the upper half of the BanRep target range, strong quarantines made headline inflation go down to record lows on the back of weaker demand and temporary factors that weighed against prices (third chart). First, the government provided a temporary subsidy to the low-income population that pushed headline inflation down by more than -100 bps during the first four months of the quarantine. Additionally, DANE had to adjust some extraordinary education-fee measurements that temporarily brought education inflation to -5.02% y/y in the YTD figure up to November. After the November print, we expect inflation to end 2020 at around 1.6% y/y. We think that these temporary effects will vanish by Q2-2021 and will bring headline inflation back to levels close to 3% by the end of next year. In the meantime, 2021 will start with even lower headline inflation due to a high statistical base effect in foodstuff prices.

All the above is in line with our expectation that the BanRep will stay on the sidelines for at least the first half of next year (fourth chart). A smaller-than-expected negative output gap; inflation expectations that are still close to 3% y/y for the 1-yr and 2-yr tenors despite downward headline surprises in the last two months; and a neutral rate that, according to the BanRep’s staff, is around 1.5% in real terms, all lead us to anticipate that the Board will try to keep its key policy rate at 1.75% for as long as it can before the expected rebound of inflation in H2-2021. At that point, the ongoing consolidation in the economic recovery would imply a gradual normalization of monetary policy to end 2021 with the BanRep’s headline rate at 2.75%.

Mexico—Lessons from 2020 and a Look at 2021

Mario Correa, Economic Research Director

52.55.5123.2683 (Mexico)

mcorrea@scotiacb.com.mx

Saying that there is an unusually high degree of uncertainty in the economic outlook was already a cliché at the end of 2019 and, after the huge surprises of 2020, it is now a standard disclaimer. At the end of 2019, a recovery of 1.0% y/y in Mexico’s GDP was expected for 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic changed the outlook dramatically, producing the deepest contraction since 1932, expected at -9.1% y/y. Unprecedented levels were reached in various indicators, along with extreme volatility in financial markets. There was also a sad and regrettable loss of more than 110k human lives, making Mexico the country with the 4th most COVID-19 deaths in the world. More than 390k firms have closed and nearly 2.9 million jobs have been lost.

At the end of 2020, the Mexican economy is recovering at differing speeds across its major sectors. On the one hand, manufacturing exports have recovered quickly thanks to the US economic rebound underway. On the other hand, domestic markets remain weak, as household consumption is still well below pre-pandemic levels and investment has been severely affected, not only by the pandemic, but also by some public-policy decisions that undermined the business environment—such as the cancellation of the Constellation Brands beer plant in Mexicali. Adjustments to monetary policy have been greater than expected, as the reference interest rate was cut by -300 bps throughout the year, while Banco de Mexico provided a package of different measures worth 750 billion pesos to support financial markets. Fiscal policy, on the other hand, provided scant relief worth only 0.7% of GDP, mainly through existing social programs—considerably less than in most countries. This decision produced a better public-debt-to-GDP ratio against Mexico’s peers, which was enough for two of the rating agencies, Fitch and Standard & Poor’s, to maintain the current debt rating and outlook. Coupled with an international financial environment flooded with liquidity and optimism generated by the vaccines against COVID-19, this helped to produce a significant appreciation of the MXN, which reached levels below 20 pesos per USD in the first half of December.

Looking ahead to 2021, a recovery in economic activity is expected among economists, but the pace, strength and sustainability of such a recovery are subject to different factors. Note that we will conduct a more in-depth revision of the macroeconomic base scenario at the beginning of January, and for now we will make only a bird’s-eye-view pass of the most relevant domestic factors that will be determinative of the performance of the main economic variables.

Starting with the economic policy, the recent appointment of Ms Galia Borja to replace Javier Guzman on the Banco de Mexico Board as Deputy Governor implies that there will be a more dovish balance on the Board and, hence, a more expansive bent to monetary policy. This will depend on the performance of inflation, but after the huge drop in year-on-year inflation during November (first chart), the space for more cuts in the monetary reference interest rate in 2021 appears to be wider—especially since ex-ante real rates remain positive (second chart). One of the factors to monitor is the next minimum wage increase for 2021, which is set to be announced in the coming weeks; although it remains subject to debate, it could become a relevant factor for inflation.

On the fiscal policy side, it is expected that the government will continue with the same strategy of supporting its favoured programs while cutting spending in other areas of the budget. It is unlikely that the factors that helped to avoid a more drastic contraction in tax collection in 2020, such as the heavy pressures on high-tax payers, will produce additional material revenues in 2021. Coupled with depleted “rainy-day” funds, this will leave public revenues on a weak footing. It seems likely that tax revenues will present sub-par results in 2021. If Pemex continues to require financial support from the federal government, then pressures on public finances will rise, leading to an increased likelihood of a downgrade from the rating agencies. We previously thought that this would occur by the end of 2020 or the beginning of 2021, but now it seems that it will come by the second half of 2021. It should be noted that Moody’s has yet to give its assessment of Mexico’s debt; additionally, the other agencies have stated that they are expecting the implementation of fiscal reforms for 2022, which should be discussed and approved in the second half of 2021, depending on the results of the mid-term elections.

Of course, these elections will become the key focal point in the 2021 political environment. Up until now, the new administration has dominated Congress with Morena and its allies holding a majority. It is likely, however, that this majority could be weakened or even lost in 2021, making it more difficult for the government to make large changes in Mexico’s legal framework.

Prospective interactions with the new Biden Administration in the United States represent another key piece of the 2021 puzzle. On the one hand, trade frictions between the US and China represent opportunities to strengthen North American supply chains under the USMCA. There is optimism in many of Mexico’s regions that produce manufactured goods to export to the US. On the other hand, there are a few issues that could produce some frictions with the new US government, such as the labour elements of the USMCA and, in particular, Mexico’s strategy for its energy sector. One of President-elect Biden’s clearest and top priorities is his green energy policy, which is heading in the opposite direction of President Lopez Obrador’s approach to the energy sector.

Finally, we all want to turn the page on the COVID-19 pandemic and the new vaccines promise to provide an end to this sad story. It should be noted, however, that we still need to endure a tough time ahead, as the cold weather in the northern hemisphere coupled with the December holidays may boost contagion and increase pressure on health services. Severe and large-scale lockdowns are not discounted in the current economic forecasts and, if these lockdowns are required, there could be a second negative impact on 2021’s economic activity, with several associated risks.

Now that the December season is starting, let us hope that the year 2021 will be as unprecedented as the year 2020 was, but on the positive side of things.

Peru—2021 Will Be Different…Again

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

An election year is always challenging in Peru. Next year will be all the more so given the uncertainty regarding COVID-19 and its aftermath, as well as political turbulence which is likely to continue until a new government is in place in August 2021. There will be two key moments for Peru in 2021. One will be in April, when the COVID-19 vaccines will have arrived, and the presidential and congressional elections will take place (a second presidential round is likely in May). The second moment will be the change in government itself. The next government should stand on more solid ground: it will be the first elected Presidency since 2018, Congress will have a different profile, with fewer inharmonious voices, and we should see the reappearance of a solid governing party, though it may not have a majority.

Another change due in 2021 is designation of a new seven-member Board of Directors at the BCRP, the central bank. It is not certain whether its current President, Julio Velarde, will continue at the helm or retire after 15 years. Although the BCRP is a strong institution, the designation of the new board members will be crucial if Velarde were to retire.

The road until the change in government could be rocky. Following the designation of Francisco Sagasti as interim president, political uncertainty has not dissipated, as we had hoped, and new fronts of social conflict have emerged. An additional risk is that Congress may accelerate its production of questionable laws until August. The next regime will have to deal with this legacy.

We are not changing our forecasts for 2021. Most of our forecast for 2020 are playing out fairly well, which gives us comfort regarding our forecasts for 2021, despite heightened political and social uncertainty. Our forecast for 2020 real GDP (-11.5% y/y) may fall a bit short, as it requires a -3.3% y/y decline in Q4 2020, but the margin of error is not that great (first chart). We are maintaining our forecast of an 8.7% y/y rebound in GDP in 2021, below consensus, which Latinfocus puts at 9.1% y/y. With so much uncertainty, it seems wise to be cautious.

Peru is emerging from COVID-19 and the lockdown with a much larger income-distribution gap. Unemployment is the key issue. In Lima, the unemployment rate jumped from 6.3% a year ago, to 16.4% currently (October), and we expect it to struggle to come down to 10% by the end of 2021. One hopeful sign as we end 2020 is that recent private and public investment data have been exceeding our expectations. However, it’s not easy to envision private and public investment growth continuing to accelerate in 2021 given that it’s an election year.

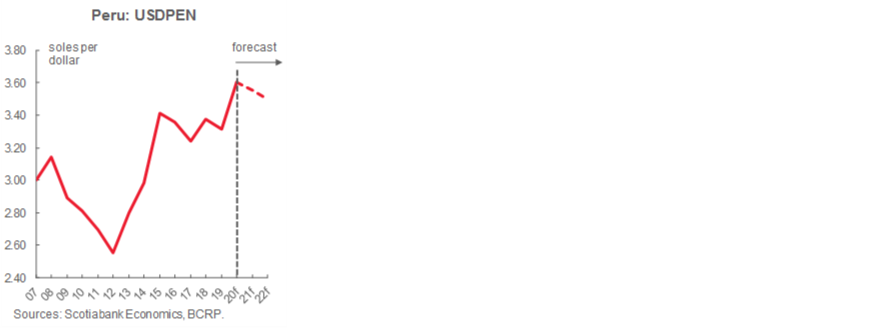

The extraordinary strength of the terms of trade with which we are poised to begin 2021 is a positive surprise, the importance of which should not be underestimated. To have copper prices hovering around USD 3.50/lb, and gold between USD 1,800 and 1,900/oz was not in anyone’s expectations at the beginning of the year. The result is that Peru’s trade balance should remain strongly in surplus in 2021, with net international reserves, already at record levels, rising even higher. Strong external accounts should support a stronger PEN as well. Our year-end 2021 forecast of 3.55 (3.60 at year-end 2020) is rather conservative in this regard, but remember that 2021 is an election year and the PEN is likely to weaken prior to the elections before strengthening later in the year (second chart).

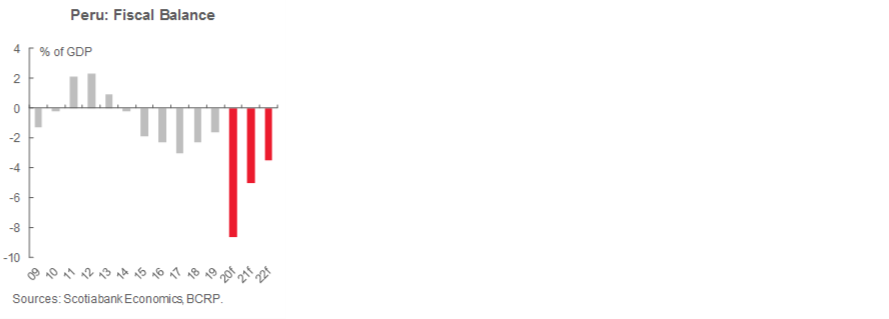

Strong metal prices will also help fiscal accounts. We maintain our forecast of an -8.7% of GDP deficit in 2020 and -5.0% in 2021 (third chart). Both are better than the official forecasts of -10% and -6.0%, respectively, as we are less optimistic about the government’s capability to meet its spending targets. However, both the government’s and our own forecasts are based on metal prices that are much more conservative than current prices, so there is upside to both.

One thing that improving terms of trade is not doing is driving investment. The past correlation between terms of trade and private investment of has broken down and will probably not be re-established until industrial overcapacity diminishes, which will take time. Thus, efforts to bolster domestic demand will depend on government spending.

Monetary policy has helped. The BCRP’s aggressive monetary expansion has prevented an interruption in payment chains and is helping both households and businesses grapple with haphazard revenue streams and liquidity needs. We expect the BCRP to keep the reference rate at 0.25% at least until the end of 2021. Price stability has been welcome, with inflation hovering consistently around the mid-point (2% y/y) of the BCRP target range. Inflation has not fallen with domestic demand, as expected, but neither are there inflationary pressures with which to contend.

Peru needs to resolve the structural issues of weak political institutions and management capabilities. The country has to stimulate growth, create jobs, and be prepared to nurse fiscal accounts back to health. At the same time, a vaccinated world should be very different in the latter half of 2021 than it is now. Peru faces its challenges bolstered by price stability, a healthy financial system, strong economic institutions, and robust external accounts.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | carlos.munoz@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabank.com.co |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.