FORECAST UPDATES

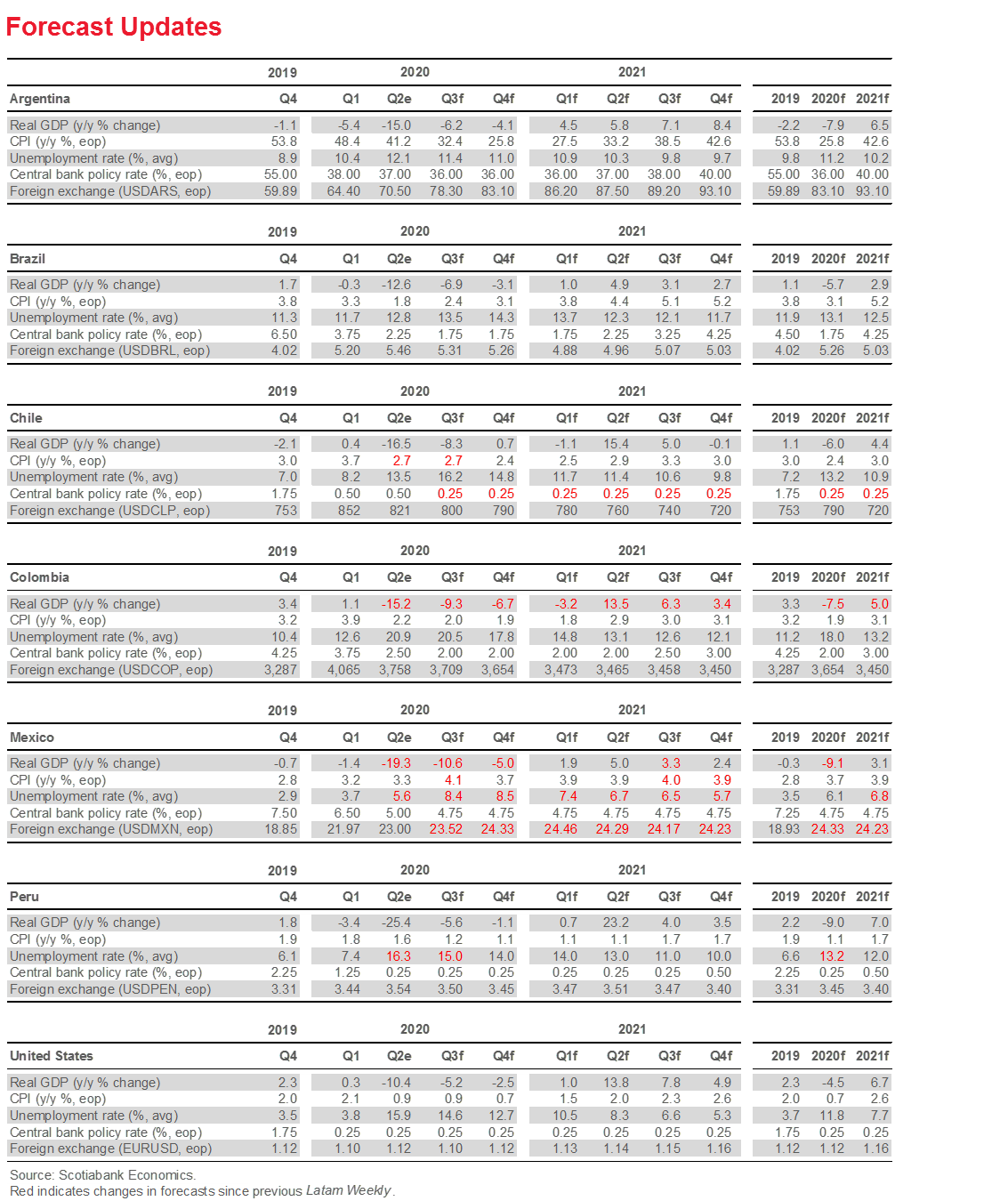

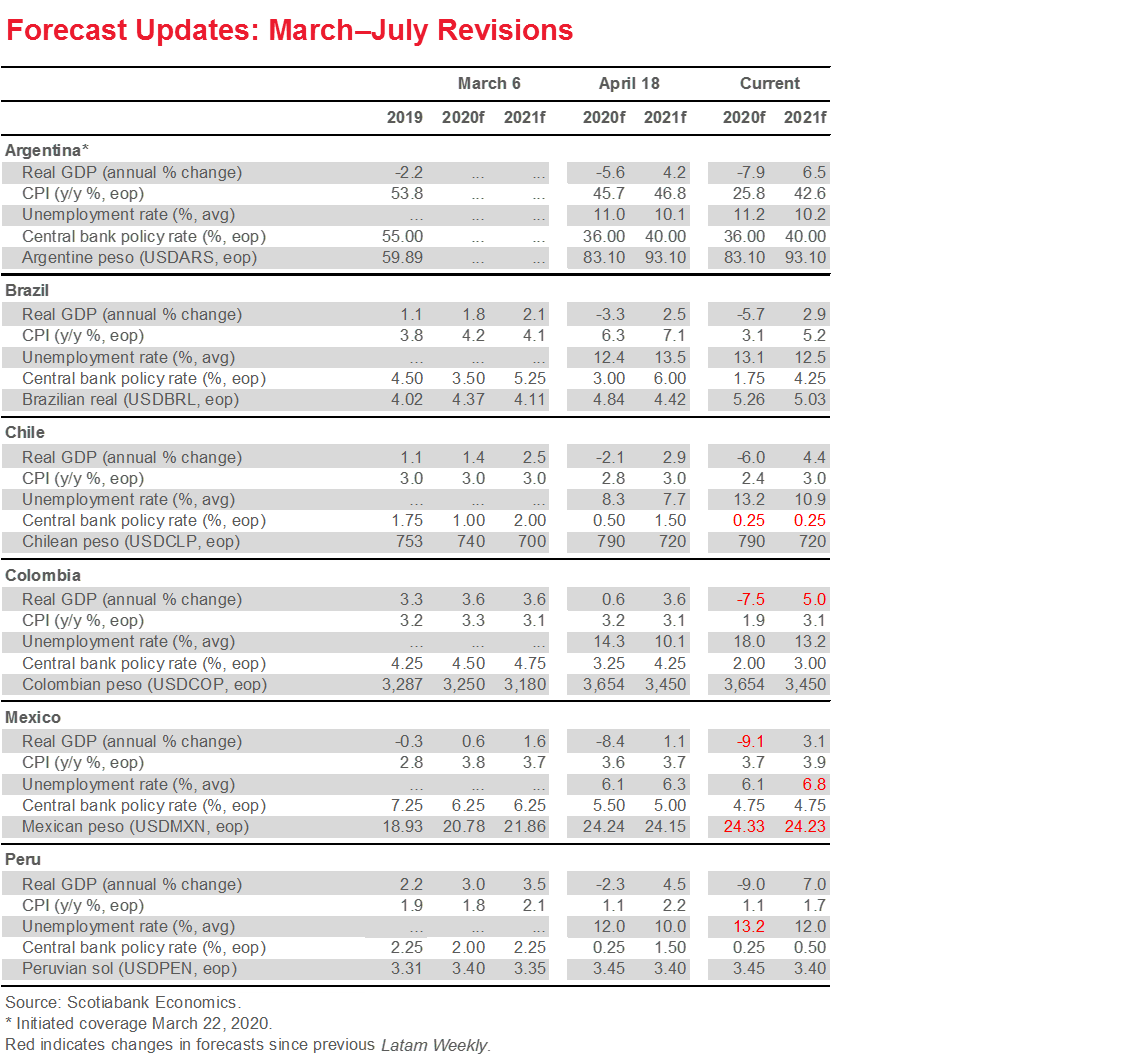

Chile’s central bank is now expected to revise downward the “technical minimum” of its key policy rate from 0.50% to 0.25% in its September Monetary Policy Report and to cut the existing rate by -25 bps to 0.25% to keep its stance fully accommodative; Colombia’s forecast downturn in 2020 has been revised from -4.9% y/y to -7.5% y/y owing to delays and reversals in the re-opening process; Mexico’s economic slide didn’t slow in May, which prompted a further cut in our 2020 growth forecast from -8.7% y/y to -9.1% y/y.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

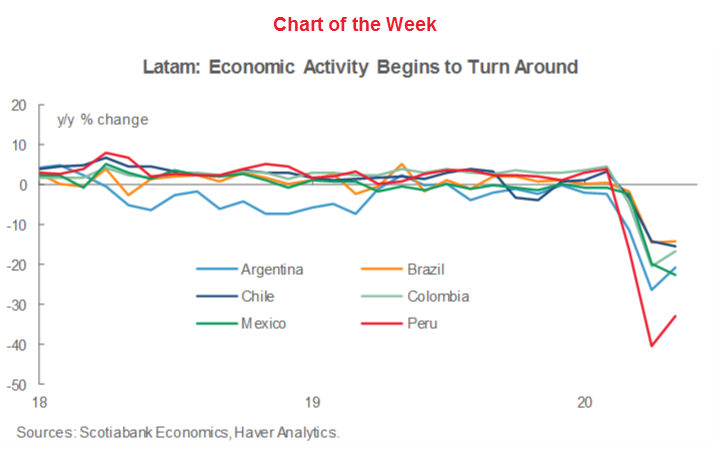

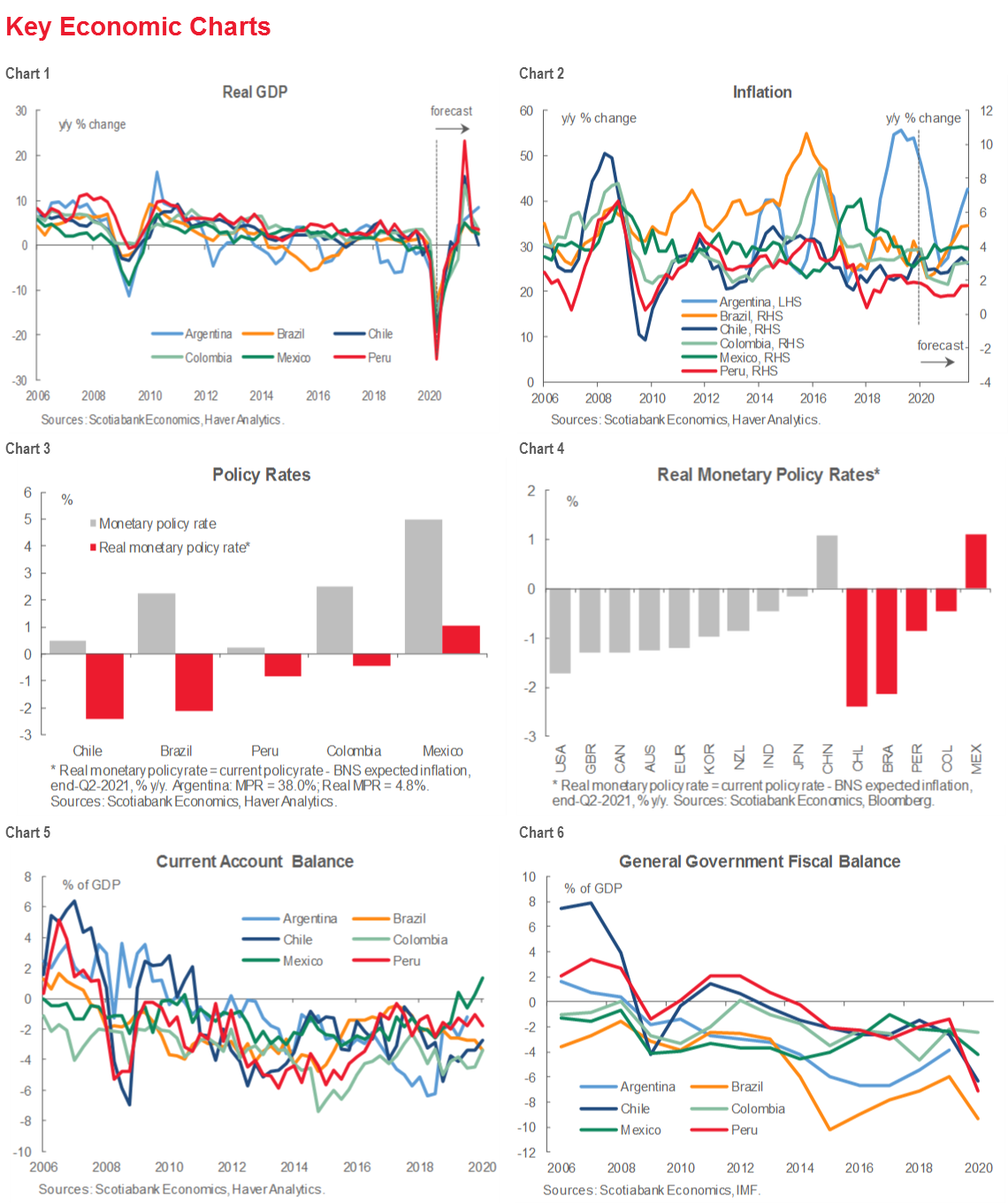

Although most of the six Latam major economies we cover saw economic activity begin to turn around in May, continued softness leads us to expect further rate cuts in the coming weeks by all of the region’s central banks except for the BCRP in Peru.

MARKETS REPORT

We look at recent measures related to pension systems across Latam and their implications for markets, with a particular focus on Mexico.

COUNTRY UPDATES

Concise analysis of recent developments and guides to the fortnight ahead in the Latam-6: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

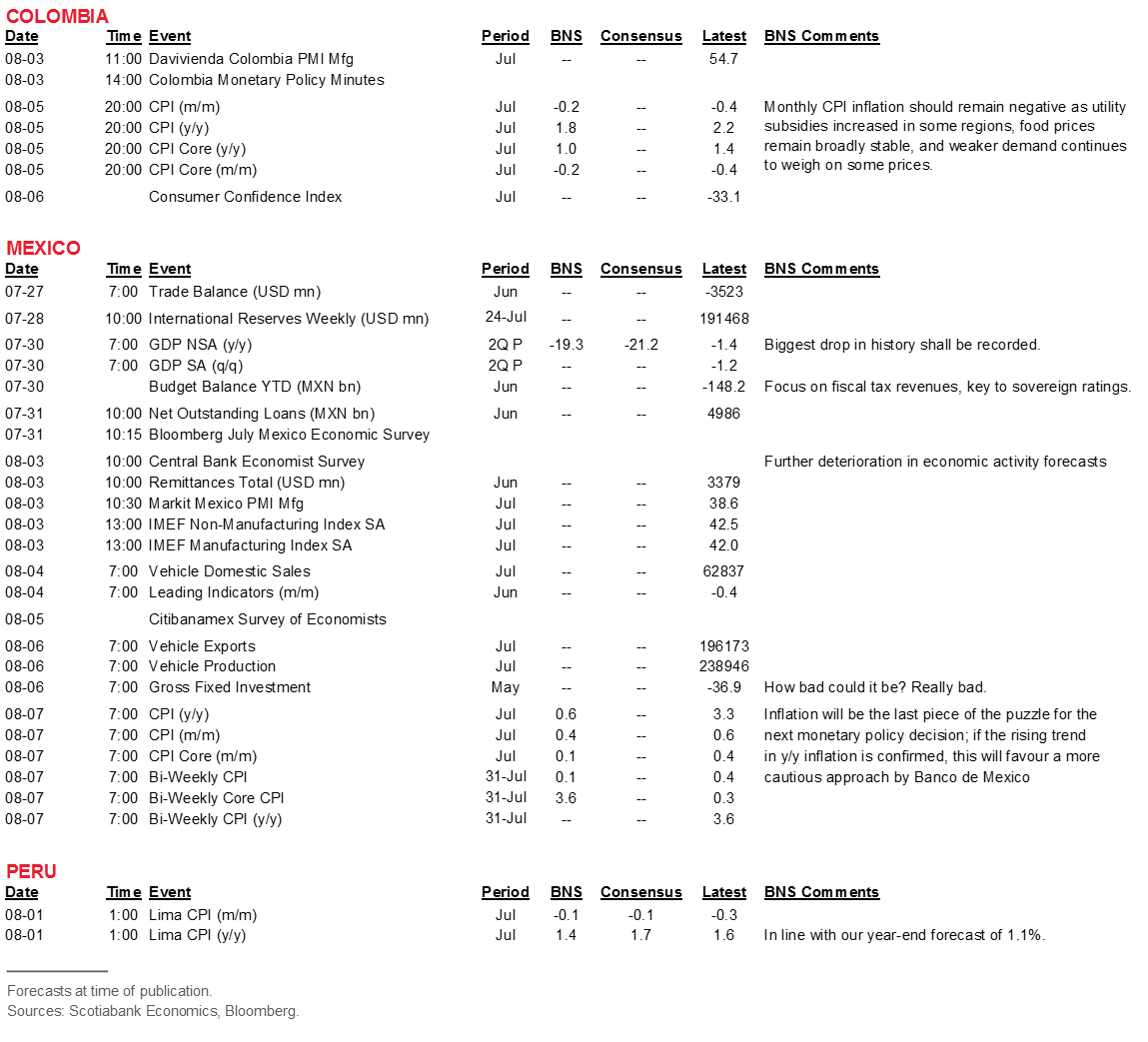

Risk calendar with selected highlights for the period July 26–August 7 across our six major Latam economies.

Economic Overview: Monetary Easing Continues

Brett House, VP & Deputy Chief Economist

416.863.7463

brett.house@scotiabank.com

While economic activity turned a corner in much of Latam in May, continued recovery will require further easing by the region’s central banks—which we expect them to deliver in the coming weeks.

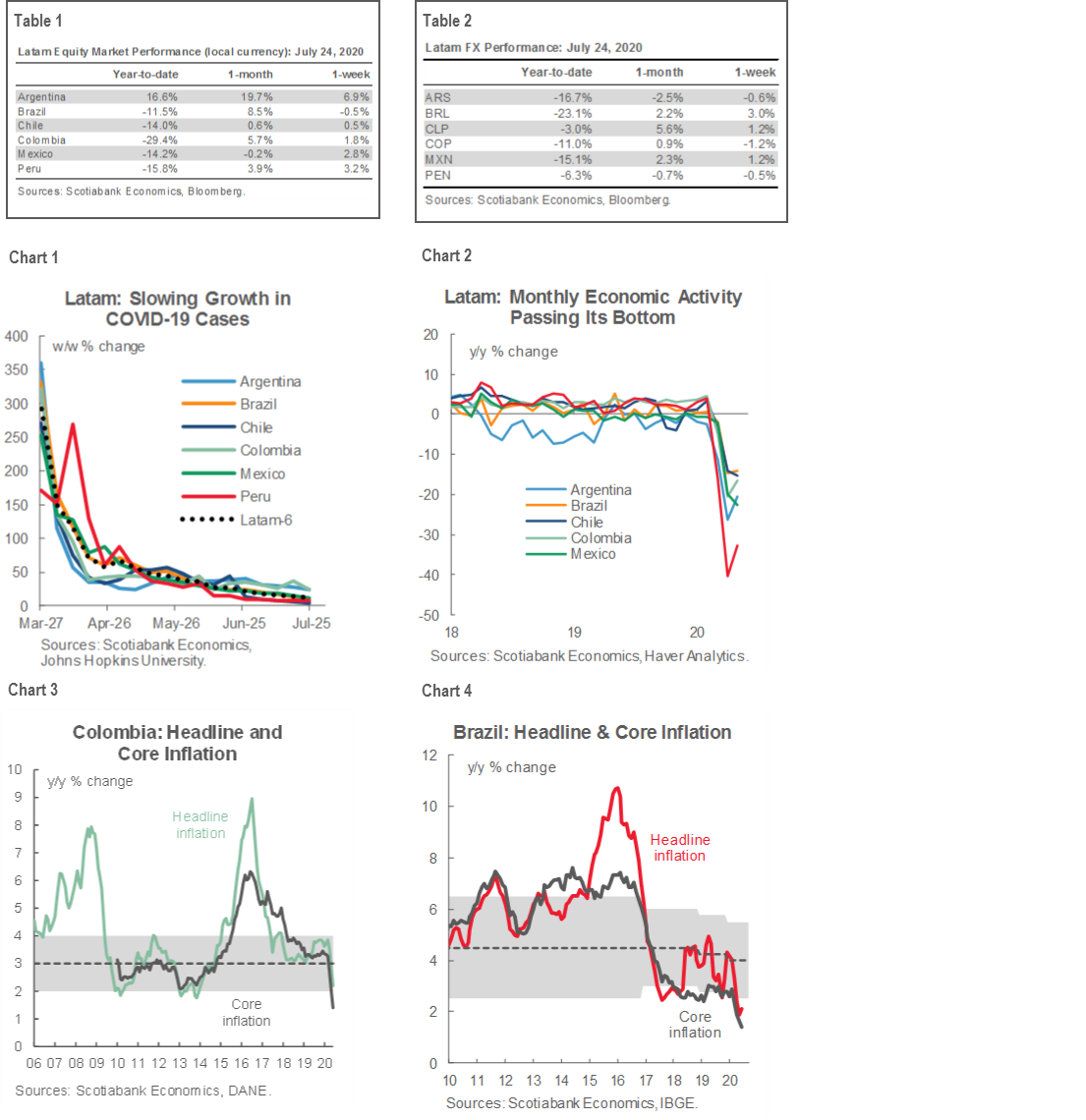

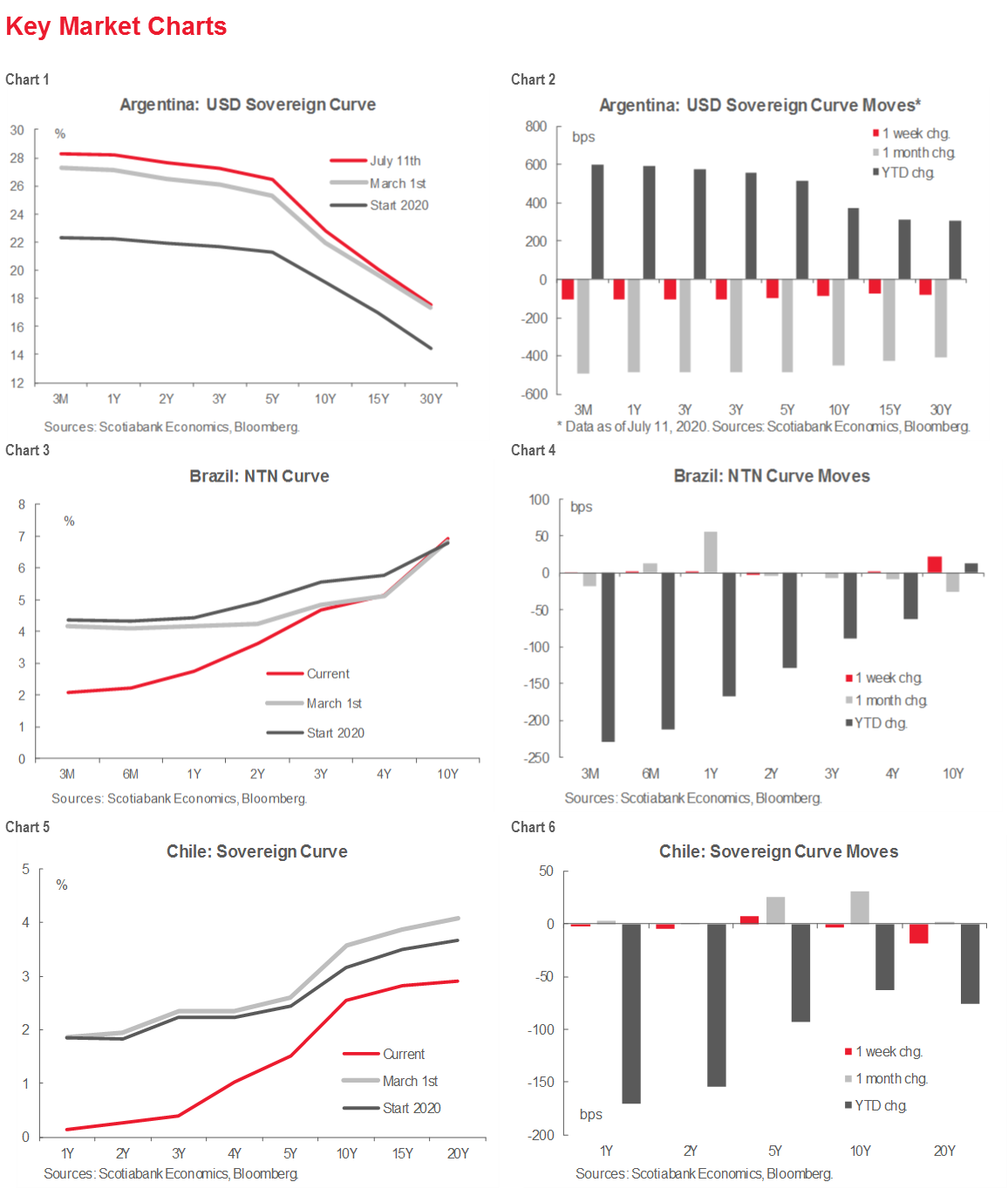

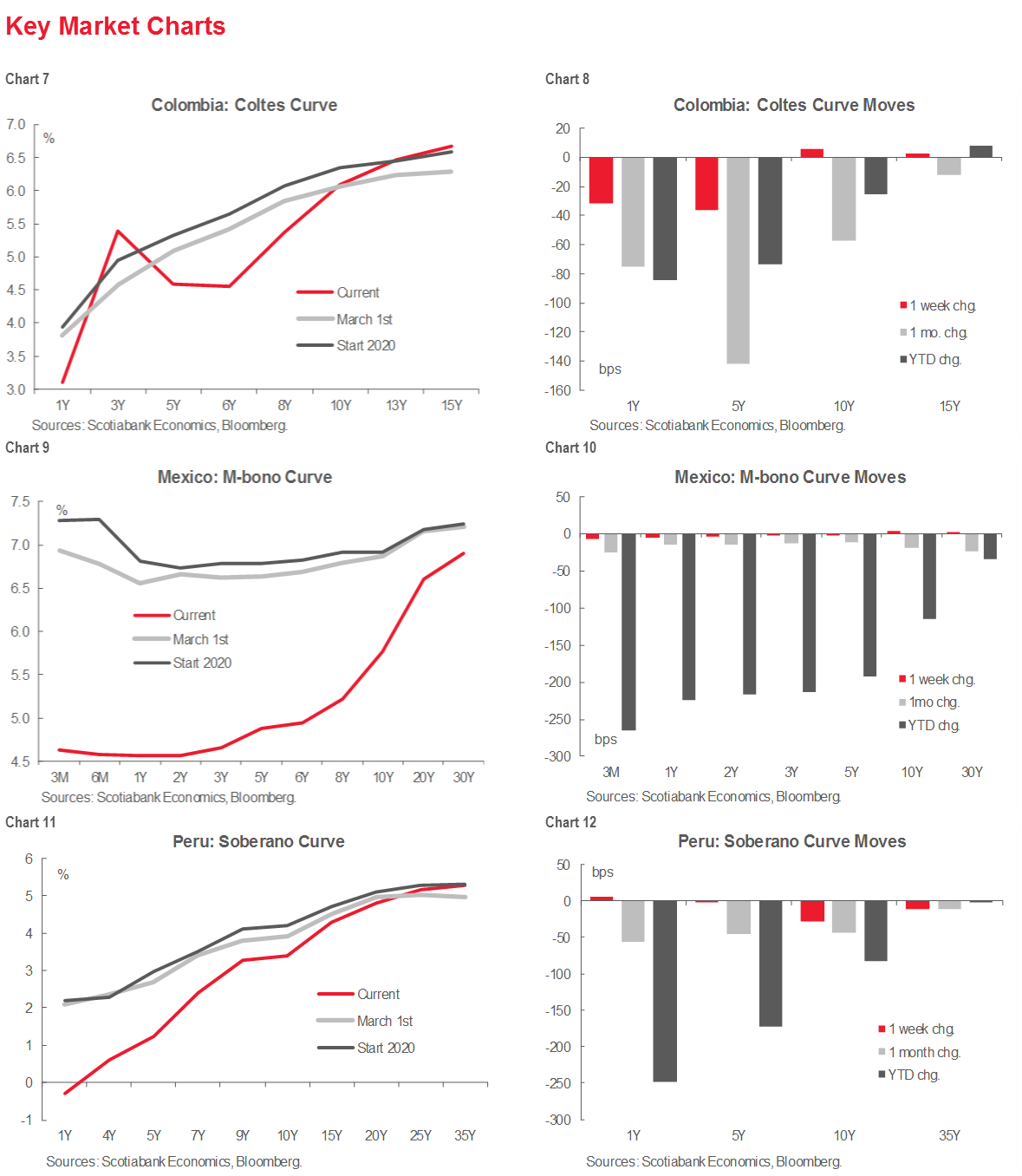

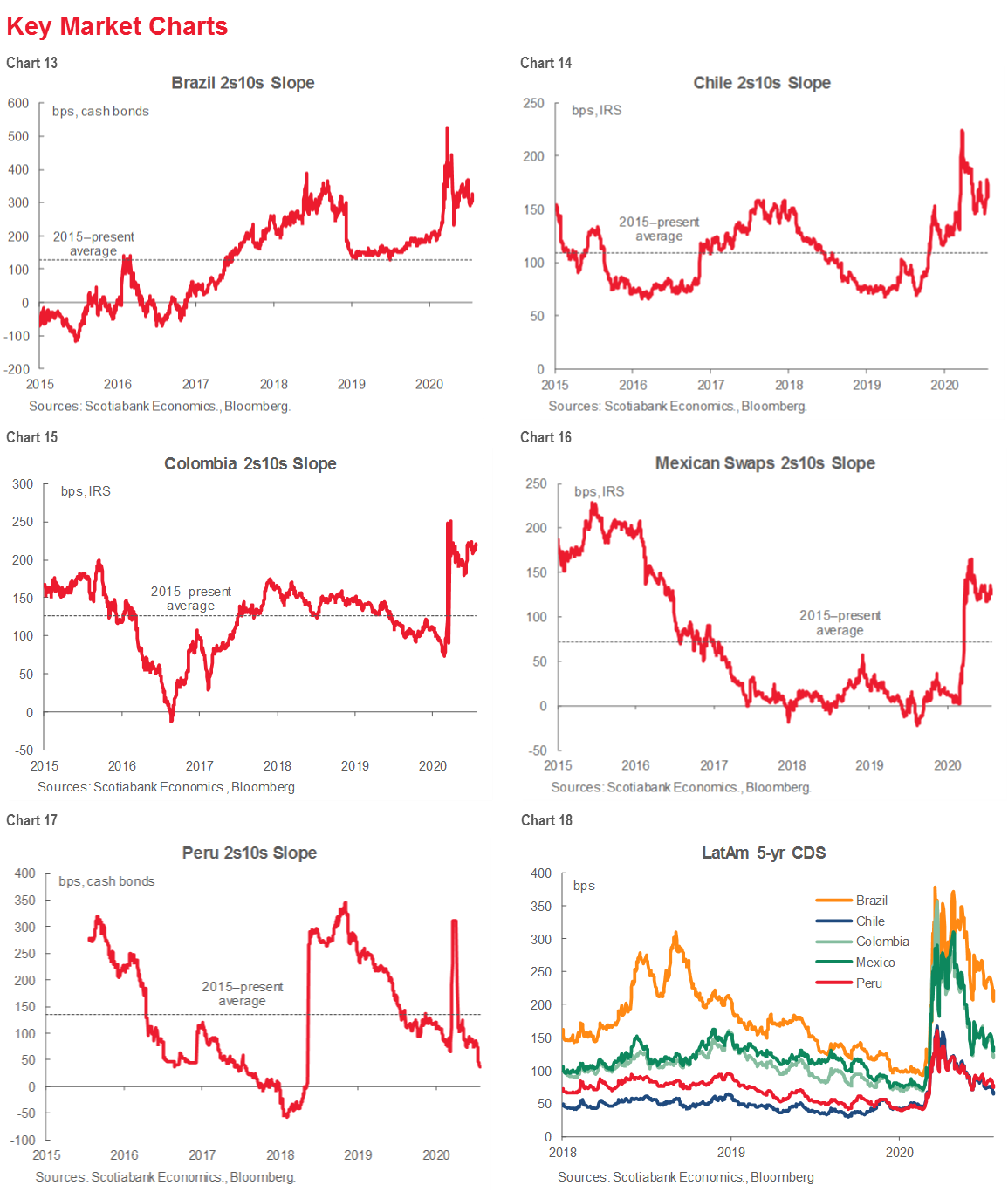

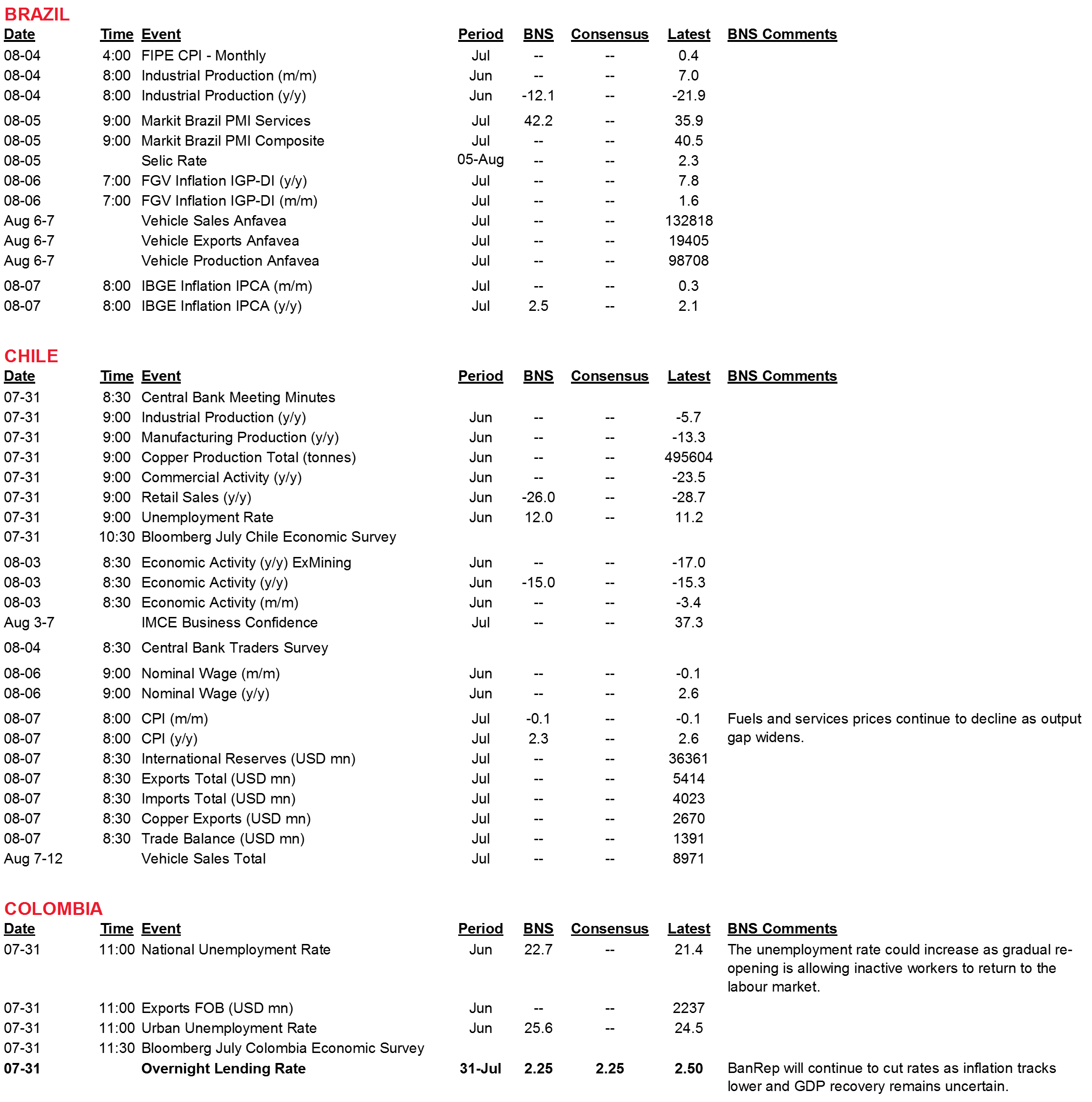

MARKET: LATAM FIRMS

Global markets ended the past week on a downbeat note with the increase in US jobless claims, the further deterioration in US-China relations, and continued bad news on the COVID-19 pandemic out of the US, but Latam risks assets saw some firming. Latam markets took their cues from both global and local developments. Equity indices were up on the week across the region, with the strongest gains in Argentina (table 1). Although major creditors united to reject the authorities’ most recent restructuring offer on the country’s USD 65 bn of external law bonds in default, the move pointed to a possible streamlining of negotiations to bridge the small remaining gap between the two sides ahead of the authorities’ current August 4 deadline on their proposal. FX markets shrugged off the advance of Chile’s so-called “10% bill” to allow early withdrawals from individual retirement accounts and the announcement of reforms to Mexico’s pension system (table 2). Sovereign yield curves were broadly stable, with some notable tightening on the shorter end of Colombia’s curve (see the Key Market Charts section).

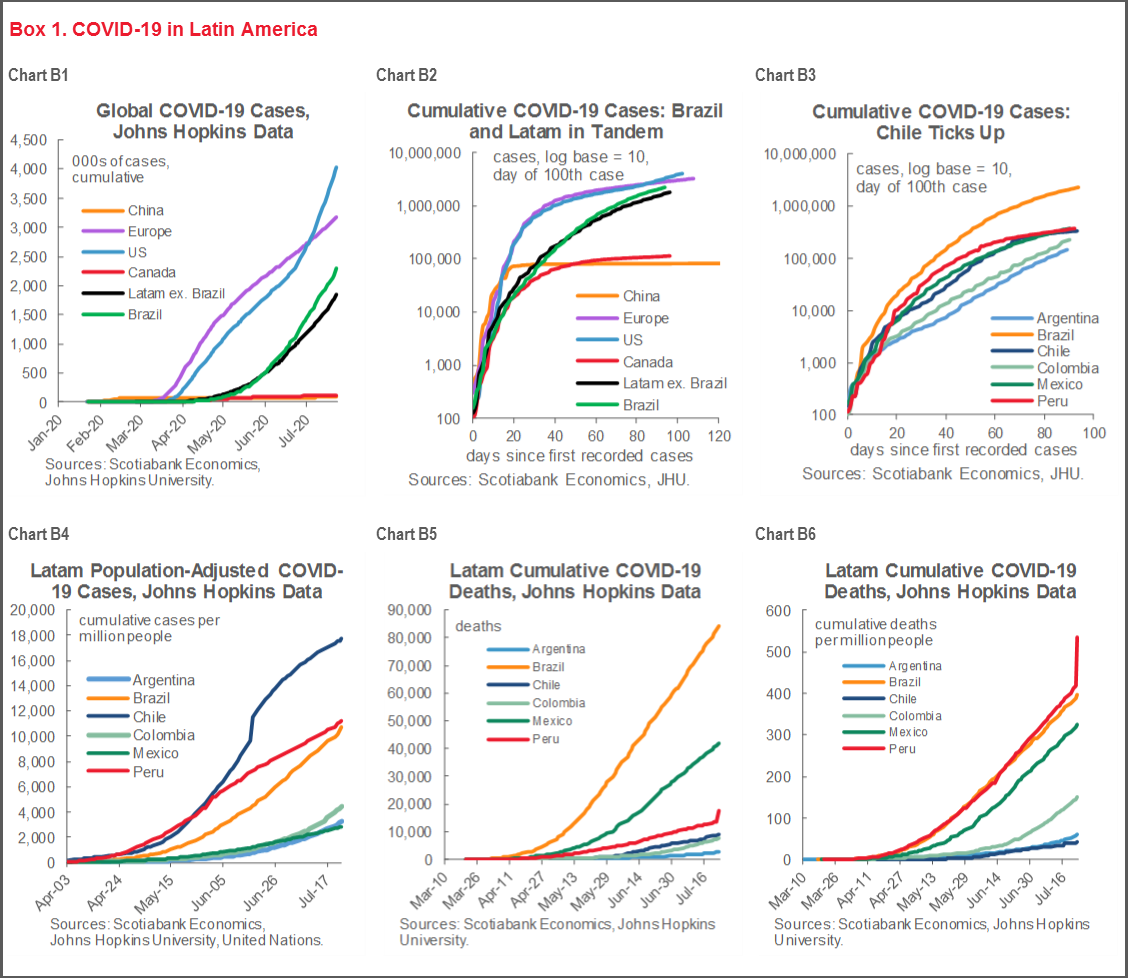

MIXED DATA AND MIXED MESSAGES

Latam hasn’t begun to cede its status as one of the global COVID-19 hot zones, but the region’s data are now sending some mixed messages on the advance of the pandemic. Across the Latam-6, growth in COVID-19 cases continues to slow on a week-on-week basis (chart 1), but our standard panel of charts (box 1) shows that Brazil’s total case numbers continue to keep it chasing the US at the dubious head of the COVID-19 global league tables. Similarly, Latam retains one of the steepest regional cumulative COVID-19 case curves in the world (charts B1 and B2). Peru and Chile’s numbers imply some progress in flattening their curves (chart B3), but these advances are threatened by a fresh outbreak in the south of Peru and the ongoing challenges in the greater Santiago region. Meanwhile, the curves in Argentina and Colombia remain unchanged from pervious weeks, justifying the re-imposition of anti-contagion measures in both countries. Chile’s recent surge in cases has moved its per capita numbers well above those of Peru and Brazil (chart B4), while new data in Peru have spiked its death numbers (charts B5 and B6).

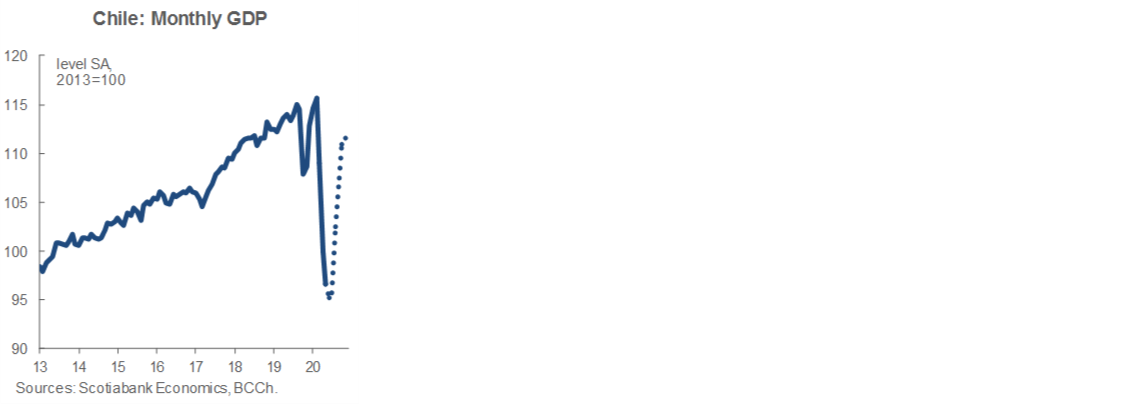

At the same time, monthly economic activity data imply that the worst of the lockdowns in April also marked the bottom for most of the region’s economies (chart 2). May GDP proxies in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru all saw some notable lifts, with Mexico’s May print the main surprise to the downside.

FORECAST REVISIONS

This edition of the Weekly sees three major adjustments to our Latam forecasts, all of which reflect the fact that economic activity has turned a corner in much of the region, but still remains soft. There are more economic corners that will need to be turned in the months ahead.

Chile. Our team in Santiago now expects Chile’s central bank (the BCCh) to revise downward the “technical minimum” of its key policy rate from 0.50% to 0.25% in its September Monetary Policy Report and to cut the existing rate by -25 bps to 0.25% to keep its stance fully accommodative.

Colombia. Colombia’s forecast downturn in 2020 has been revised from -4.9% y/y to -7.5% y/y owing to delays and reversals in the re-opening process.

Mexico. Mexico’s economic slide didn’t slow in May, which prompted our team in CDMX to impose a further reduction in our 2020 growth forecast from -8.7% y/y to -9.1% y/y.

A comprehensive review and revision of our outlook across Latam’s major economies will follow during the coming fortnight in the next edition of Scotiabank Economics’ Global Forecast Tables, along with updates to G10 and other emerging-markets forecasts.

FORTNIGHT AHEAD: MORE CENTRAL BANK EASING

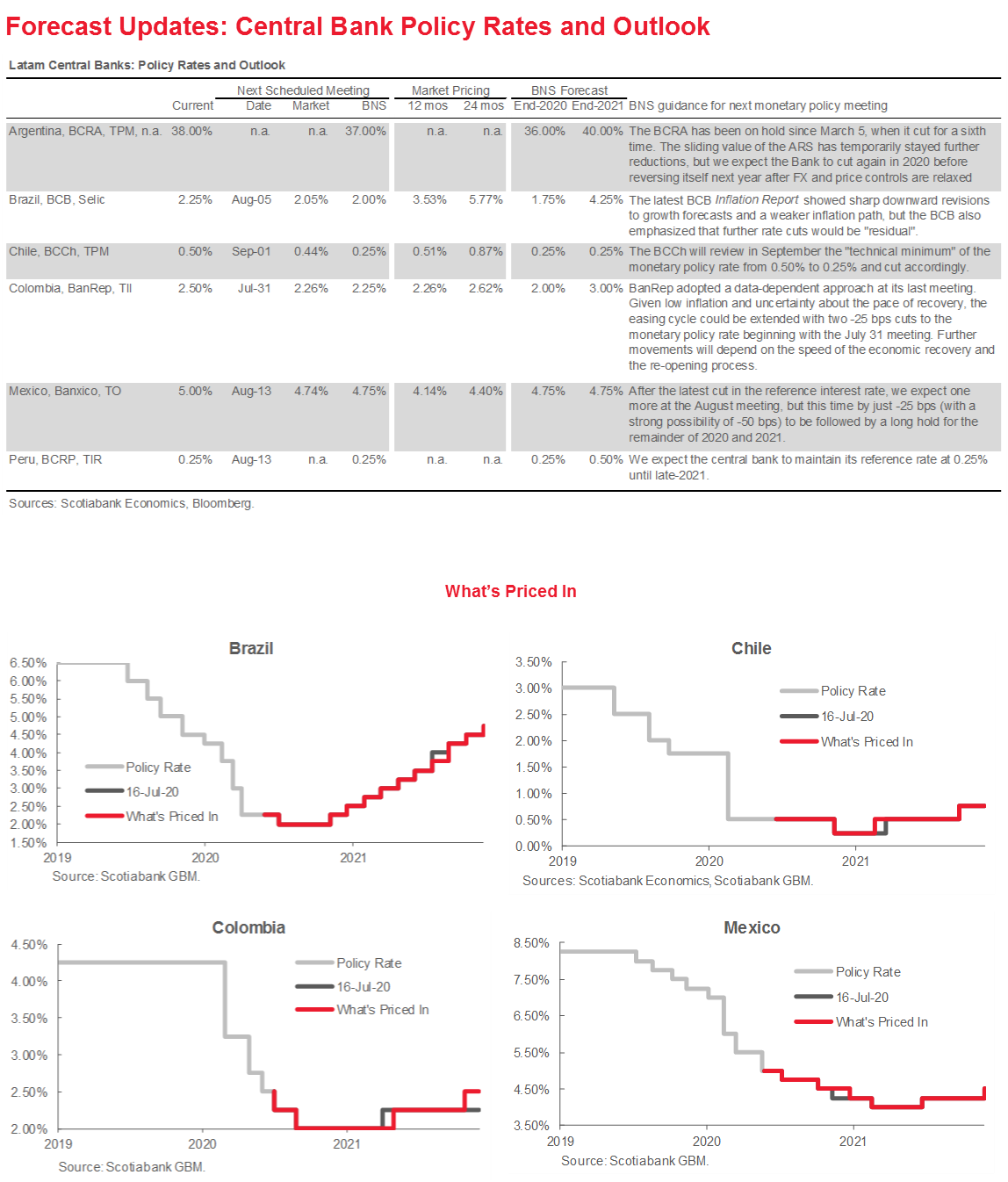

In the coming weeks, monetary policy makers are likely to echo our view that Latam’s economies have come off their pandemic bottoms, but will need more support to continue their rebound, as summarized in our Central Bank table (p. 4).

Colombia. With a pause in re-opening, a material weakening in the growth outlook, headline inflation dropping below the 3.0% target to 2.2% y/y in June, and core at 1.4% y/y (chart 3), there’s little question the BanRep will cut again on July 31. But with the need to balance domestic stimulus with stability in the country’s external accounts, gradualism is set to remain the hallmark of the BanRep’s moves with a -25 bps cut expected at each of the next two meetings.

Brazil. While the BCB has sent some mixed messages with weaker forecasts and accompanying counsel that any remaining cuts would be “residual”, headline and core inflation are well below target (chart 4) and the market has come around to pricing the -25 bps cut on August 5 that we have forecast.

Mexico. With the highest real policy rates in the region (see Key Economic Charts section), but an economic downturn in 2020 set to rival its peers with a -19% y/y contraction in Q2, Banxico has ample room to cut, and our team in CDMX signals in its country update that there is a material risk that the expectation of a -25 bps cut on August 13 could be exceeded with a -50 bps cut move.

Peru. While the BCRP isn’t likely to cut its key monetary policy rate on August 13, it retains the option to continue injecting liquidity into the economy and facilitating the government’s efforts to expand credit.

Chile. A few weeks ago, markets briefly priced another policy rate cut, from the “technical minimum” of 0.50% to 0.25%—but then reversed themselves. Our team in Santiago has taken the opposite view and expects the BCCh to revise its technical minimum downward in September and cut by -25 bps to shore up the economy.

Argentina. The BCRA hasn’t moved since March, but with Buenos Aires back under lockdown, it has a window to cut again to support domestic activity while policy controls mitigate external risks.

Markets Report: Pension Changes in Context—Mexico’s Proposal and Its Impact on Markets

Brett House, VP & Deputy Chief Economist

416.863.7463

brett.house@scotiabank.com

Tania Escobedo Jacob, Associate Director

212.225.6256 (New York)

Latam Macro Strategy

tania.escobedojacob@scotiabank.com

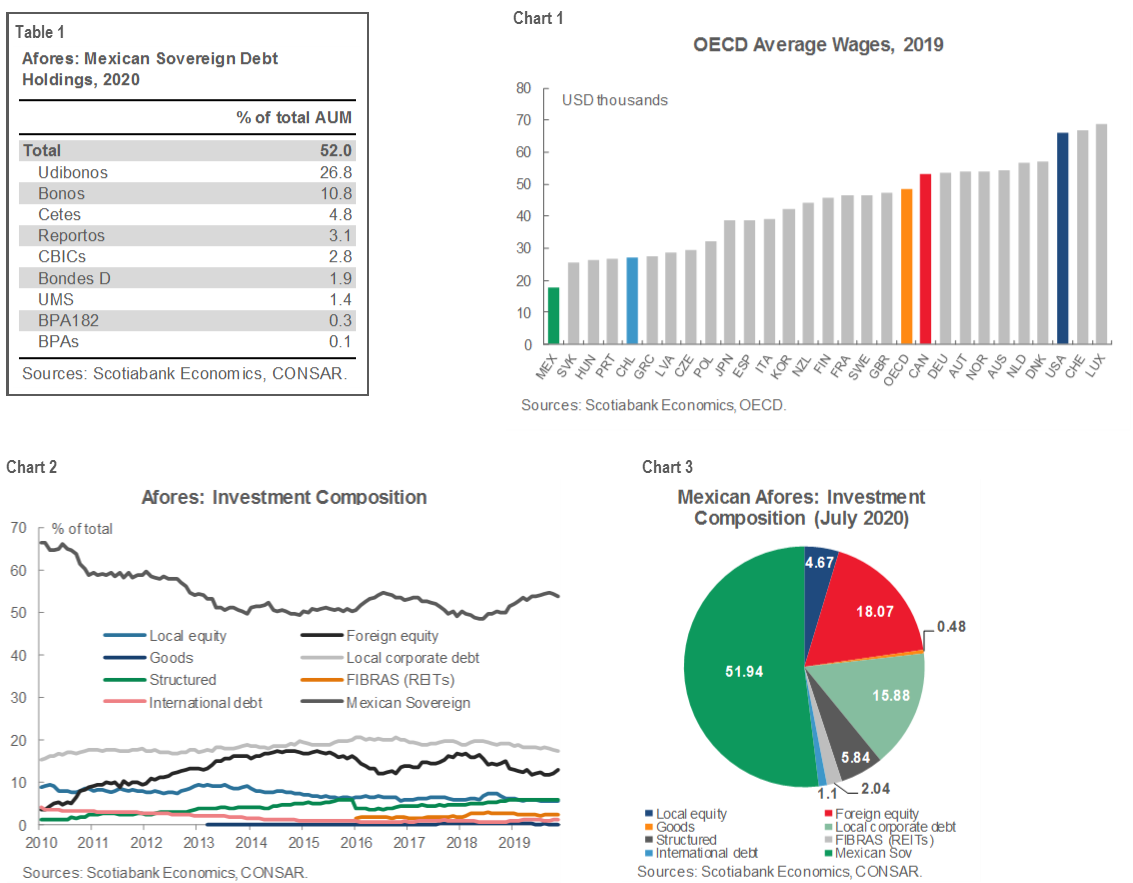

The Wednesday, July 22 announcement by President Lopez Obrador and Finance Minister Herrera of their intent to overhaul Mexico’s pension system materially lowers the probability that the country will imminently go down the same path of pension withdrawals that Chile and Peru are pursuing—or opt for other more radical possibilities such as the nationalization of private pensions.

In the short term, the removal of a source of uncertainty may be positive for Mbonos, particularly at longer maturities, and for the MXN, which has benefited from recent bursts of positive risk appetite.

In the medium to long term, Mexico’s announced reforms should lead to higher savings rates, increases in the Afores’ assets under management, and potentially, a structural increase in demand for Mexico’s local bonds, but at the possible cost of slower formal job creation and growth.

Short-term risks lie in possible changes to the Afores’ investment guidelines.

MEXICO JOINS LATAM’S PENSION REFORM CLUB, BUT ON ITS OWN TERMS

Pension changes have moved to the leading edge of policy initiatives in Latin America to shore up incomes amid measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Mexico’s July 22 announcement of a suite of proposed reforms to its pension system, initially reviewed in our July 23 Latam Daily, follows pension-related measures in Peru and Chile over the last few months. However, the modifications under consideration in Mexico—and their likely implications—are distinct from those in progress farther south in the Pacific Alliance and they materially reduce the likelihood that Mexico will follow Peru and Chile in allowing early withdrawals from its pension system.

This report dissects the possible changes to Mexico’s pension system and their implications for Mexico’s asset markets.

CONTEXT: PERU AND CHILE PRIORITIZE CURRENT INCOMES

Amongst the Latam-6, Peru took the first step this year on measures that affect pensions. Peru’s Congress voted at the end of April to allow withdrawals by individuals of up to 25% of their funds in the private pension system (i.e., the AFPs), up to a maximum of PEN 12,900 (about USD 3,600). Initial projections pegged potential withdrawals at around USD 4 bn of the total US 43 bn (equivalent to 20% of GDP) under management by the AFPs. So far about 3.9 mn applications have been submitted, which implies withdrawals could total about USD 5 bn.

At the time of the initiative’s passage, our team in Lima expected the impact on the PEN to be small and transitory even though some 40% of AFP funds are held offshore and asset sales are likely to be focused on liquid foreign assets. The AFP withdrawals fall at the same time as the Peruvian government seeks to finance the region’s largest (as a share of GDP) fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which we expect to cause some bear steepening in Peru’s sovereign curve, as we detailed in the “Markets Report” section of the June 27 Latam Weekly.

Chile has followed Peru’s lead on broadly similar terms. Congress has passed a bill that will allow citizens to withdraw 10% of their assets in Chile’s AFPs, with a minimum draw of around USD 1,250 and a maximum of around USD 5,400. The bill was approved by Chile’s Chamber of Deputies on July 15, passed by the Senate on July 23, moved back to the Lower House for ratification, and sent to the President for signature. It is set to be published in the Official Gazette this week. Current projections anticipate eventual withdrawals of up to USD 20 bn of the total US 200 bn managed by Chile’s AFPs. We also took stock of the market impact of Chile’s changes in our July 11 Latam Weekly.

It’s notable that in both Peru and Chile, these pension initiatives have been driven by the national legislatures and were opposed by Executives that have eventually acceded to the changes. Supporters warned that Chile could see a resumption of October’s protests if the President were to try to block the bill.

CONTAGION TO MEXICAN MARKETS

While Peru’s measures did not appear to have an immediate impact on Mexican markets, Mexico’s Mbono curve has widened by around 20 bps as the proposed Chilean pension modifications have moved toward passage into law. The shift in Mexico’s curve has come about amid extremely low liquidity and despite relative stability in the MXN and reasonably calm general market conditions. CDS spreads have also been stable, reflecting comparative quiet with respect to idiosyncratic country risk on the political and economic fronts.

The link between pension developments in Chile and Mexico’s markets has followed on two tracks.

First, some market participants have argued that Chile’s AFPs might liquidate a significant portion of their Mbono holdings to finance withdrawal requests. On the contrary, we think that the Chilean AFPs would prefer to sell more liquid assets such as deposits and lower yielding instruments like US Treasuries, leaving steadier its holdings of higher-yielding paper. According to publicly available data, Chilean pension funds own a maximum of USD 1.5 bn in Mexican bonds, which compares with an average daily trading volume of around USD 1.3 bn in the Mbono market. Mexican assets rank eighth versus other countries (including China) in terms of exposure for the AFPs. While there may be some selling of Mbonos, we think that this pressure will be limited.

Second, the widening in Mexico’s curve has also reflected a concern that changes to allow withdrawals from retirement accounts, like the initiatives in Peru and Chile, could be implemented in Mexico. But we believe that the proposals announced by AMLO and Min. Herrera on Wednesday make such withdrawals less likely in Mexico. In this, Mexico joins Brazil and Colombia in staking out an approach distinct from that in Peru and Chile (see box 1).

MEXICAN REFORMS FOCUSED ON GREATER SAVINGS, NOT IMMEDIATE CASH RELIEF

In general terms, the proposal presented this week to overhaul the Mexican pension system, aims to tackle the two main problems plaguing country’s retirement system:

Contributions to the system, and therefore, total retirement savings, are too low; and

The large informal sector in Mexico means that most people do not have access to the pension system and are unable to gain access later in life since at least 24 years of contributions are needed to qualify for a minimum guaranteed pension.

With these two challenges in mind, the government’s new reform proposals consist of two main sets of changes, and—in contrast with Peru and Chile’s reforms—don’t feature early withdrawals.

Increased and more focused contributions

Increased total employee and employer contributions to individual worker retirement accounts would rise from 6.5% of wage income to 15% through the following means:

Employers have agreed to increase their contributions from 5.15% to 13.875% over the course of eight years; while

Workers’ contributions will hold steady at 1.125% of their wage income. It would have been preferable to see an increase in this low rate, but the politics and practicality of such a more would be difficult when Mexican wages remain so low

(chart 1).

The government’s contribution, which is currently set at 0.225%, will be re-focused on low-income workers in the formal sector. At present, the government makes contributions to retirement accounts of employees earning up to 15x the monthly value of the Unit of Measurement (UMA) of USD 1,650. The ceiling for government contributions will be lowered to incomes equivalent to 4x the monthly value of the UMA (USD 440). For incomes between 1x and 4x the monthly UMA, the government contribution will be calculated on a progressively sliding scale, falling from 8.725% for those on incomes of 1x the monthly UMA to 1.75% for those on 4x the monthly UMA.

Easier qualification

The minimum retirement age will remain at 60 years, but the thresholds for qualification will be eased. The number of weeks of contributions required to gain access to a minimum guaranteed pension (as opposed to pension payments funded only by the assets in an individual retirement account) will be reduced from 1,250 weeks (i.e., 24 years) to 750 weeks (about 14.4 years). This should more than double the share of workers eligible for the benefit.

No early withdrawals

Just as important as what’s in the Mexican pension proposal is what isn’t. Early or immediate withdrawals from individual retirement accounts don’t feature in the Mexican government’s reform package.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INDIVIDUALS

For Mexicans, the reforms are set to raise substantially the average size of pensions and widen eligibility. Overall, the reforms should raise the average value of minimum guaranteed pensions from MXN 3,289 (USD 147) to MXN 4,345 (USD 194), which should facilitate an increase in the average income replacement ratio to around 40%. The government also hopes that the changes will widen the scope of people who have access to minimum guaranteed pensions from 34% to 82% of Mexico’s working population. According to the authorities, the reforms would also make 97% of workers eligible for at least some kind of pension, up from 56% at present.

SHORT- AND LONG-TERM MARKET IMPACT

In the short-term, we think the announcement is positive both for the long end of the Mbono curve and for the MXN. As the “10% bill” has advanced in Chile, we have perceived that some offshore accounts have hit the pause button on Mexican asset markets because of the possibility that Mexico could go down the same road of pension reform as that taken in Peru and Chile. We think the likelihood of this happening has been materially diminished by this week’s proposal from the AMLO Administration, which could prompt some flows back into Mbonos, particularly at the long end. Reduced uncertainty should also be positive for the MXN, which has been lifted by recent increases in risk appetite. Contingent on global conditions, last week’s developments could provide the push needed for USDMXN to test and perhaps break through the 22.20 level.

In the medium to long term, the moves to raise savings rates and increase contributions to Mexico’s individual retirement accounts could lead to a rise in assets under management by the Afores on top of the USD 190 bn they currently have under their care—which could underpin a gradual structural increase in demand for local bonds. According to some informal calculations from the Ministry of Finance, the reforms are intended to increase contributions by about MXN 11 bn

(USD 0.5 bn) each year over the next eight years. If future asset allocation decisions by the Afores remain close to historical patterns, about half of these resources could be directed to local sovereign debt (charts 2 and 3, table 1), which would imply, all other things being equal, lower interest rates over time.

The government has indicated that it would expect the Afores to lower their commissions and management fees to align them with “global standards”. In broad terms, this would be consistent with a reduction from the 0.92% currently charged in Mexico to around 0.7%. The authorities indicated that this is intended to provide the Afores with incentives to look actively for investments with higher yields in areas such as infrastructure or construction—which could be successful if the Afores are left to optimize their allocation processes. We will monitor developments closely for any moves to change the Afores’ investment guidelines.

NEXT STEPS: PASSAGE IN THE AUTUMN, WORSE ALTERNATIVES AVERTED

The business community has indicated its endorsement of the proposed Mexican reforms, which could help speed their passage. The President of the Mexican Chamber of Industry (CCE in Spanish), Carlos Salazar, has underscored that the government’s proposal reflects consultation and cooperation between industry, the government, labour unions, and even Congress to ensure reasonable eligibility criteria, produce adequate savings for retirees, and enable retirement incomes that exceed the poverty line. This approach may reflect an effort to repair some of the recent cracks in the relationship between industry and the government, which soured after the AMLO Administration decided not to provide some fiscal aid to larger corporations The fact that the increase in employer contributions was designed and negotiated with industry representatives is a positive; additionally, its gradual phase-in should help cushion its immediate costs and allow firms to adapt to it. Still, small- and medium-sized enterprises that operate with lower margins are likely to feel the impact of the changes more immediately and keenly, with possible negative effects on formal job creation and growth.

The bill to enact the reforms proposed this week will be discussed by lawmakers in September and it appears to have a good chance of being approved by Congress. Even opposition politicians have indicated their support for the reforms on a first glance. The bill’s progress will depend on its finer details, which have not yet been spelled out in public. The final text of the bill should be determined by October.

The biggest positive of this set of reforms is what it avoids: it now looks unlikely that Mexico will replicate the moves toward early pension withdrawals in Peru and Chile. In fact, Mexico’s reforms go in the opposite direction by increasing savings now in exchange for larger retirement payments later. We believe these reforms also take off the table more radical possibilities such as the nationalization of the Mexican Afore system and the transition into one public fund.

Box 1. LATAM’S OTHER MAJOR ECONOMIES AREN’T SET TO FOLLOW PERU AND CHILE

Brazil. As part of its package of economic and financial measures to combat COVID-19, Brazil has accelerated the 13th month of pension payments to retirees to put additional money in seniors’ pockets. Additional pension reforms have not yet been advanced.

Colombia. Colombia has already floated possible changes to its pension framework. For context, Colombia’s public pension system is structurally in deficit since contributions are insufficient to cover existing obligations. This gap is habitually funded out of current government revenue. But the pandemic-induced decline in economic activity has caused a contraction in government revenue equivalent to several percentage points of GDP, which, if left unaddressed, would leave the authorities without enough liquidity to cover pension payments coming due.

The government has moved to take on future pension liabilities from the private system in exchange for immediate cash-flow relief. As we noted in April, the government issued Decree 588 to authorize the transfer of approximately COP 5 tn (USD 1.5 bn, 0.5% GDP) from the private retirement accounts of people receiving pensions equivalent to one minimum-wage salary to the Colpensiones state-owned system. These transfers had been delayed pending a decision on their constitutionality, and on Friday, July 23, Colombia’s Constitutional Court ruled against them.

In mid-June, Finance Minister Carrasquilla was reported to have been considering a move to permit one-off withdrawals from retirement accounts for people directly affected by the current crisis, similar to the changes in Peru and Chile. In response, the belly and long end of the sovereign yield curve widened by about 48 bps and the authorities disavowed this option.

More recently, the government has been emphatic that any eventual pension reforms would focus on reducing inequality and expanding pension coverage. In any event, proposals to allow withdrawals from retirement accounts would be unlikely to receive Congressional support.

COUNTRY UPDATES

Argentina—Time to Get a Touch Sweeter

Brett House, VP & Deputy Chief Economist

416.863.7463

brett.house@scotiabank.com

Almost everything on Argentina’s calendar for the next fortnight is secondary to the ongoing negotiations on Argentina’s external debt restructuring whose current offer period ends on Tuesday, August 4. We continue to expect an arrangement will be agreed with a collection of creditors that would satisfy the authorities’ minimum participation thresholds and allow the proposed swap to go ahead—but a deal may not be reached by the current deadline. Although three major creditor groups united on Monday, July 20, to oppose the authorities’ fourth and so-called “final” set of offer terms, this was likely a positive development for an eventual deal as it could reflect a new alignment of various creditor interests and demands. Negotiations could be streamlined from this point onward and we continue to think that they will be focused on a state-contingent sweetener to close what is now a small gap between Argentina’s proposal and the bondholders’ demands. A move to revisit the authorities’ export-based value recovery mechanism idea or a GDP-linked warrant could come prior to August 4 or in the long interregnum leading up to the current September 3 swap execution date.

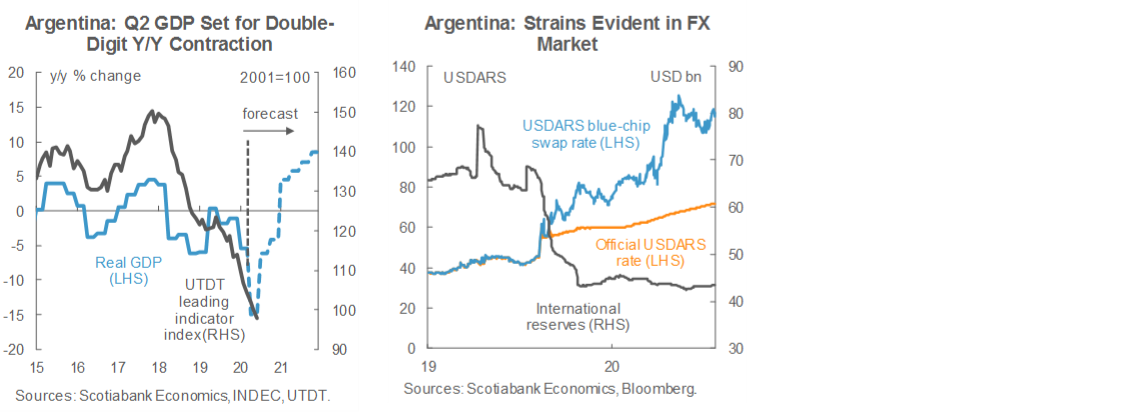

In the meantime, Argentina’s economy appears to have turned the corner from the worst of April’s lockdowns, but it remains in seriously depressed territory. Economic activity in May rose by 10% from April’s month-long quarantine, but this still leaves activity about 20% lower than a year ago and on par with levels last seen about a decade back. Leading indicators aren’t pointing to a strong enough rebound to lift the economy out of a third year of recession (first chart), even with recent progress on the country’s efforts to restructure its domestic- and foreign-law sovereign bonds. The blue-chip exchange rate rose again this past week and is just off the record levels that it reached in May (second chart).

The next two weeks will see the release of indicators that may confirm some further lift from April’s lows—or point to new softness from the extension of quarantine measures into mid-July. June trade data arrive on Tuesday, July 28, and are likely to reflect a mixed set of influences. We expect June’s trade surplus to retreat from recent highs as the further re-opening of some industrial production and the temporary relaxation of some quarantine measures likely provided a boost to import demand. Exports likely held steady in June, but may have received some support from agricultural goods that have been held back in anticipation of more substantial ARS depreciation. May wage growth, out on Thursday, July 30, is a stale indicator given that we already have June inflation.

Looking beyond trade and wages, we would focus instead on a trio of indicators with more forward-looking implications. July tax revenue, out Tuesday, August 4, should see a third straight month of gains on the back of increased economic activity across the country. June industrial production and construction activity numbers should show strong month-on-month gains from late-May’s tentative re-openings. Also on August 5, the auto sector will provide the first data points for July. Production in June reached 65% of 2019 levels and should continue to climb to about 80% of year-ago numbers in July.

Brazil—Tax Reform Proposal Still Leaves Lots of Work to Do in Stabilizing Fiscal Trajectory

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

Over the past couple of weeks, we would argue that the most meaningful development in Brazil on the macro front has been the delivery to Congress of the first part of the authorities’ tax reform. Although, as of now, we are not sure the proposed changes are ambitious enough to quite deserve being called a “reform”, they are steps in the right direction. As we wrote last week, the country doesn’t have much room to increase tax rates given that the government already absorbs about 1/3 of GDP and—at the same time—the large fiscal deficit of close to 9% of GDP expected for 2020 doesn’t leave space for tax cuts.

We tend to see the government’s focus on simplifying the tax code, as the PIS-Cofins merger does, as positive in view of the inefficiencies that the current byzantine tax system imposes on businesses. However, we would argue that important steps on spending rationalization and efficiency enhancements are likely the places where most space exists to improve the fiscal situation—although these political battles would be particularly tough and this is not the right economic environment in which to fight them. History implies that the type of fiscal changes required in Brazil are implemented in one of two ways: (1) during a “proper fiscal crisis”, such as the 16 percentage point of GDP fiscal adjustment that Mexico was forced to implement in the early 1980s or the adjustment of around half that size that Greece undertook during the 2010 GFC; or, alternatively (2) during a concerted and sustained effort—which would need to carry over into future governments.

Over the next two weeks, we will get quite a solid view of how the economy has been faring during June and July. We anticipate that the pace of formal job destruction will slow by about half in June (to -176k per month), in line with our view of overall activity for the month and consistent with the important rebounds we saw in June PMIs, especially on the manufacturing side (which surprisingly printed in expansion territory for June). For industrial production we expect a strong improvement, but anticipate that the year-on-year contraction will remain large (-12%), with activities such as construction providing drag. For July, on the manufacturing PMI front, we think the positive print we saw for June was an outlier and expect it will turn back into a small contraction for July. However, we anticipate that the Markit services PMI will post a robust bounce while still remaining in contractionary territory.

One of the variables we have been monitoring in order to re-assess our BCB call (where we still look for two “tweaks” of -25 bps) is the performance of the Brazilian yield curve. As the BCB determines how much room it has left, our sense is that the anchoring of the long end of the curve is a critical factor. The continued fall of long-end rates along with short-end rates over the past month is supportive of our view that there is still a little room to provide further stimulus. However, DIs are only pricing about 60% odds of one final -25 bps cut in either of the coming two meetings, and nothing after that.

Chile—Re-Opening Begins; Bill to Allow the Withdrawal of Pension Funds advances in Congress

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2939.1092 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Carlos Muñoz, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.6848 (Chile)

carlos.munoz@scotiabank.cl

On Sunday, July 19, the Chilean Government presented the details of its re-opening plan for the economy. The plan “Paso a Paso”, consists of five stages and aims to gradually resume activities considering the epidemiological indicators of each community and region of the country. The authorities assured that these measures are not permanent: if health indicators worsen in a specific area, it may go back to a previous stage or to a new quarantine to control the spread of the virus.

The details of each phase are described below:

1. Quarantine: This includes limited mobility to minimize virus interaction and spread. Gran Santiago is in the quarantine phase right now.

2. Transition: This phase reduces the degree of confinement while avoiding abrupt re-openings to minimize the risk of contagion. In this phase, quarantine is lifted on weekdays and maintained on weekends and holidays. Social gatherings are restricted to no more than 10 people. Curfew and physical distance measures are maintained, in addition to “sanitary belts” around some protected cities that restrict access by outsiders. People over 75 years of age have to be in mandatory quarantine. People are allowed to go out, except during curfew. Moving to a second home is prohibited.

3. Preparation: Quarantine is lifted for the general population, but maintained for high-risk groups. Social and recreational activities are allowed any day of the week with a maximum of 50 people. Prohibition of moving to a second home remains in place.

4. Initial opening: Certain activities with a lower risk of contagion are resumed: the reopening of cafes, restaurants and cinemas—with capacity restrictions—is allowed, plus a gradual plan of return to classrooms is activated. The regions of Los Ríos and Aysén, in the south of Chile, have been in this phase since Monday, July 13.

5. Advanced opening: An increase in the maximum number of people allowed at gatherings and activities is allowed, always with hygiene measures in place. Moving to a second home becomes possible and restrictions on the mobility of adults over 75 years of age are lifted.

According to the pension fund regulator, around USD 20 bn could be withdrawn from pension funds (AFPs) once the “10% bill” is approved. We expect the AFPs to sell their most liquid assets, including sovereign bonds and assets invested overseas, to meet withdrawal demands. We anticipate that the AFPs will not sell proportionately as many corporate bonds and Chilean stocks. It is important to recall, also, that there is a bill currently under discussion by Congress that would allow the central bank (BCCh) to purchase Chilean sovereign bonds in the secondary market. This initiative, which is likely to be approved, would alleviate some of the burdens that the AFPs could face in complying with withdrawal requests and would mitigate the creation of distortions in the long end of the sovereign yield curve. In addition, we expect the BCCh and the financial markets regulator to issue some guidelines in order to minimize any impact on interest rates and on financial markets in general. According to the Budgetary Office of the Treasury, pension withdrawals could have an impact of USD 6 bn on the public budget owing to lower tax revenues and higher expenditures to driven, in part, by government obligations to make up pension shortfalls.

This coming week on Friday, July 31, we will receive sectoral activity and employment data for June. We forecast that the unemployment rate will reach 12% in the moving quarter April-May-June, while we anticipate a contraction of around -26% y/y for retail sales in June. With these numbers in hand, we estimate that monthly GDP for June, which will be released on Monday, August 3, fell by around -15% y/y: a large share of the country’s territory, including Gran Santiago, spent the whole of the month under confinement. For the July CPI print, which will be released on Friday, August 7, we forecast a monthly variation of -0.1% to 0%. Fuel prices have continued to fall, in addition to those for services, which have experienced downward pressures owing to the weakening of domestic activity.

Colombia—More-Gradual-than-Expected Reopening Weighs on the Expected Pace of Economic Recovery

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@co.scotiabank.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@co.scotiabank.com

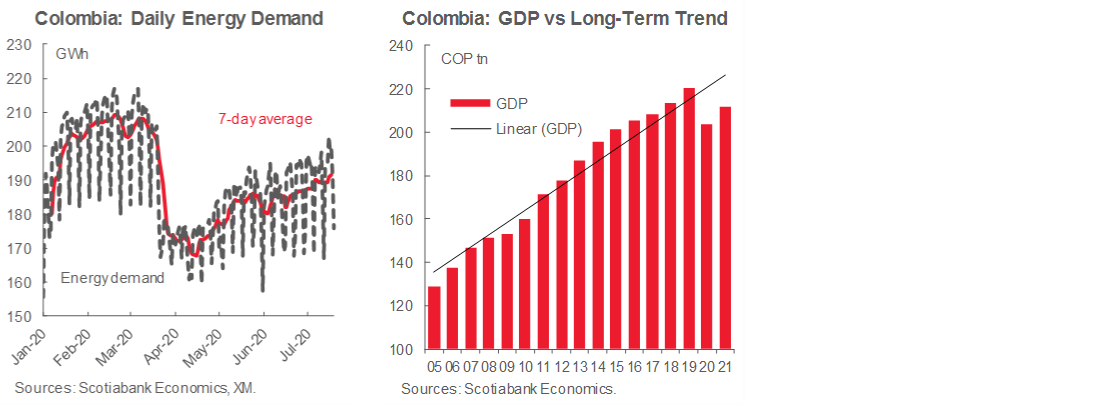

The strict lockdown in Colombia started in the last week of March and lasted 33 days. After this initial lockdown, the government decided to re-open economic activity gradually, which worked very well in its initial stages. For instance, leading indicators such as energy demand recovered almost a third of lost demand in fifteen days. Additionally, gasoline demand also improved by 30% in May. Anonymized, aggregated Scotiabank Colpatria data on credit and debit card expenditures showed a more gradual recovery path in May, but still featured encouraging signs.

In June, virus challenges looked under control. Cases per million remained below 60 and the health system was functioning well, which allowed regional governments to allow a range of activities to resume. However, in July, increasing contagion started to crowd the health system. Therefore, local governments decided to stop the re-opening process and to take additional measures, such as lockdowns by neighbourhoods in Bogota (which generates 26% of GDP) and a “4x3 system” in Medellin (Antioquia region accounts for 14% of GDP), which features four days of open activities followed by three days of total lockdown. Barranquilla (Atlantico region covers 4.4% of GDP) and Cartagena (Bolivar produces 3.6% of GDP) still remain close to strict lockdown.

Although May data showed improvements and confirmed that economic activity touched its bottom in April, new city restrictions, the delay in re-opening of additional sectors, and the adverse effects of lower internal and external demand are worsening our recovery outlook for 2020. In particular, some essential activities that initially were intended to lead economic growth are suffering negative demand pressures due to high uncertainty and lower household income, and they are overshadowing better results in sectors that started the re-opening process earlier.

All of the above leads us to again revise down 2020 GDP growth from -4.9% to -7.5% y/y. This revision includes all three quarters that have not yet printed in 2020. May hard data anticipate Q2-2020 GDP growth of around -15% y/y instead of the -10.6% that we had previously anticipated. Additionally, according to our calculations, new lockdown measures imply a stagnation of the re-opening process, which makes us revise Q3-2020 GDP growth down to -9.3% y/y from our previous -6.8%. Finally, we measure some second-round effects of the new partial lockdowns in terms of a slower speed of re-opening that will also affect Q4-2020. Therefore, we have also revised down Q4-2020 to -6.7% y/y from -3.3%. All in all, our new 2020 GDP forecast is -7.5% y/y, 2.5 ppts lower than the previous projection. Finally, for 2021 although we raised our forecast to 5% y/y, this was mainly due to statistical base effects. In fact, a 5% recovery still involves, according to our calculations, an economic loss between -6% and -7% compared to “potential” GDP, and an extra 3 million unemployed people (12% of the pre-COVID-19 labour force) by the end of 2020.

In the next couple of weeks, June unemployment data will be released on Friday, July 31, and we expect further deterioration in the unemployment rate due to some return of the inactive population to the job market. The central bank, BanRep, will also meet on July 31. Markets have aligned with our view that expects a -25 bps rate cut to 2.25% as inflation continues to slow and the economic recovery is uncertain. On Wednesday, August 5, DANE will release the CPI data for July; we again expect a repeat of May’s negative month-on-month change since some prices have been hit by weaker demand (clothing) even though some governmental aid increased in July.

Mexico—Contagion Continued to Hit the Economy; Proposed Retirement Funds Reform

Mario Correa, Economic Research Director

52.55.5123.2683 (Mexico)

mcorrea@scotiacb.com.mx

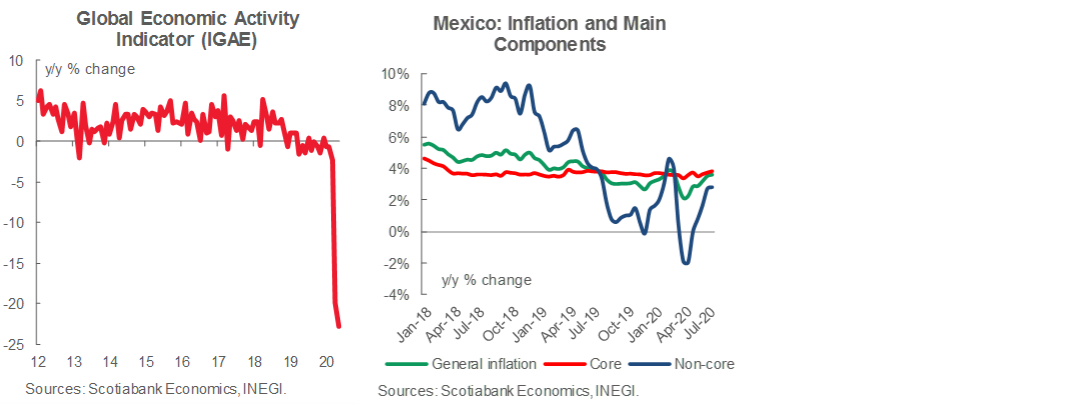

COVID-19 contagion remains stubbornly on the rise in the world and, while other countries are experiencing a second wave, Mexico hasn’t yet reached the peak of its first one. Recent economic indicators revealed the nasty wounds to the economy from pandemic containment measures. The Global Indicator of Economic Activity (IGAE) plummeted by -22.7% y/y in real terms in May, below the market forecast of -20.0%. While the primary sector managed to grow a little, at 2.5% y/y, there were record contractions in the services sector (-20.3% y/y) and industry (-30.7% y/y). Instead of showing a timid recovery in May, when a few restrictions on some economic activities eased, the level of production kept falling.

Inflation presented a new surprise in the first half of July, posting a 0.36% 2w/2w increase while the markets were expecting 0.29%; core inflation was 0.25% 2w/2w when markets anticipated 0.13%. General inflation reached 3.59% y/y, which is the highest since February 2020, and core inflation hit 3.84% y/y, the highest in the last twelve months. There is a clear dichotomy within Mexico’s price data, with services prices basically tamed while merchandise prices are quite dynamic. Even though inflationary pressures appear to be concentrated on particular sectors, overall price indices will likely remain on the rise in the coming months. This will be a key consideration for Banco de Mexico in their next monetary policy decisions, where the central question will concern whether more cuts to the reference interest rates are justified when inflation is rising. We still believe that Banxico will cut the reference interest rate by -25 bps in August, with a strong possibility of a -50 bps reduction; and then stop the easing cycle.

In other data, real commercial activity fell -23.7% y/y in May, making for two consecutive months of sharp declines. Formal jobs fell by 83.3k in June, according to the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), which sums to 983k jobs lost during Q2. Consumer confidence recovered a little bit in July, but remains at very low levels, at 32 points, signaling future weakness in consumption.

In an interesting development, the federal government presented a proposal on July 22 to reform the retirement funds system, which received backing from the business community and was well-received by the markets (see the Markets Report section for more details). This reform is aimed at improving the conditions for retirement of the working class, easing the conditions to get a pension, and significantly increasing the mandatory contributions—with business doing the heavy-lifting to make all of this happen. According to the government, the initiative would help to increase, on average, the pension of workers affiliated with the IMSS by 42%. The proposal includes three main actions:

An increase in the total pension contribution from 6.5% to 15.0% of workers’ wages, to be phased in over eight years, by increasing employers’ contributions from 5.15% to 13.875%, while holding workers’ contributions steady at 1.125%. Additionally, the government contribution, currently at 0.225%, will be concentrated on workers with monthly incomes up to 4x the monthly value of the Unit of Measurement (UMA)—around USD 440 for 2020;

A reduction in the time required to gain access to a minimum guaranteed pension from 1,250 to 750 weeks; and

An increase in the average value of the minimum guaranteed monthly pension, from MXN 3,289 (USD 147) to MXN 4,345 (USD 194), which should facilitate growth in the average replacement ratio to 40%.

The good news is that there is a concrete proposal to address the serious problem of the under-funded retirement system. The not-so-good news is that this reform will add to the already heavy social burden on firms, which could become an incentive for even greater informality and discourage formal job creation.

Finally, on the political front, after the decision to give the control of ports and customs to the Navy, the Minister of Communications and Transportation, Javier Jimenez Espriu, resigned, and the President acknowledged a difference of opinions as the cause. The new Minister will be Jorge Arganiz Díaz Leal, who formerly worked with the Mexico City Government when AMLO was the Mayor.

The coming weeks are loaded with relevant information, starring the GDP advance estimate for Q2 on Thursday, July 30. Figures for the June trade balance on Monday, July 27, will give us an early indication of the economy’s recovery as exports and imports should start showing some improvement. Results for the Banco de Mexico July survey of private economists will be released on Monday, August 3; June numbers for the budget balance (July 30), remittances (August 3), and outstanding credit (July 31) will also be important data points. Later in the coming fortnight, figures for private domestic consumption and gross fixed investment (August 6) for the month of May will be published. Finally, inflation numbers for the whole month of July will provide on August 7 the last pieces of information for Banco de Mexico to consider in its next monetary policy decision, scheduled for August 13.

Peru—July 28 Presidential Address Should Outline Government Strategy on COVID-19, the Economy, and Its Relationship with Congress

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

On July 28, President Vizcarra will deliver the annual President’s Address to the Nation. The event will be particularly crucial this year, given the health crisis, the state of the economy, and the conduct of the newly restructured Cabinet.

There has been a clear resurgence in COVID-19 contagion since July 1, when the quarantine was lifted. President Vizcarra will need to address this issue. Although the new Minister of Health, Pilar Mazzetti, has mentioned the possibility of a new quarantine, one that is nationwide in scope does not seem feasible. However, certain regions could come under an intensified lockdown. Currently, COVID-19 contagion is spreading mostly in the southern part of the country. This could potentially affect certain rather important mining operations in the region.

Expectations are also high regarding what Pres. Vizcarra may say—and the new Cabinet propose—in terms of economic recovery. The new Cabinet, given its composition, promises to be more private investment friendly. For example, the Head of the Cabinet, Pedro Cateriano, has signalled that the government would seek to promote mining investments.

Finally, Pres. Vizcarra will probably seek to define the type of relationship the government—and new Cabinet—will seek with Congress. This has been a point of contention in the past.

Although these issues are likely to be addressed to some extent by the President, the details on these fronts will likely be given on August 4 when the new Cateriano Cabinet will present its governing plan to Congress.

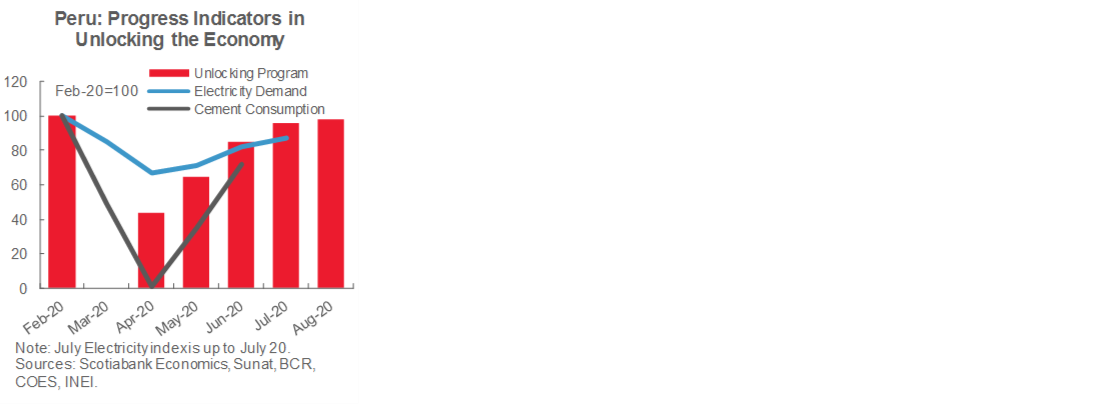

Meanwhile, recent data on the economic recovery have been moderately encouraging. Phase 3 is being completed, with 96% of the economy allowed to operate—at least to the extent that company solvency, individual market demand, and compliance with protocols, permit. The most recent sectors to open include domestic flights and commercial land travel on July 15, and on-premises restaurant service (at 40% capacity), on July 20.

Furthermore, according to sector representatives, home sales were currently running at 90% of pre-COVID-19 levels. Cement demand rose 128% m/m in June. Even though demand in June was still 26% lower than a year earlier, the increase from May to June points to a nice recovery. June marked only Phase 2 in the recovery plan, and the increase is likely to have continued in July, when Phase 3 began.

Unemployment rose to 16.3% in Q2-2020, surpassing our forecast of 15.0% for the quarter. This amounts to 2.7 million jobs lost during the lockdown. Both figures—jobs lost and the unemployment rate—are likely to be their peak numbers for 2020. We had originally considered that unemployment would peak at 16% in Q3-2020, rather than Q2. As it is, the impact of the lockdown on employment has been stronger than expected. However, on the positive side, the unlocking of the economy has been faster than originally thought, so unemployment is not likely to continue rising in Q3 and we are revising our Q3-2020 forecast down to 15.5%, from 16%.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | carlos.munoz@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | pirajaj@colptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including, Scotiabanc Inc.; Citadel Hill Advisors L.L.C.; The Bank of Nova Scotia Trust Company of New York; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Limited; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa S.A. de C.V., Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., and Scotia Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.