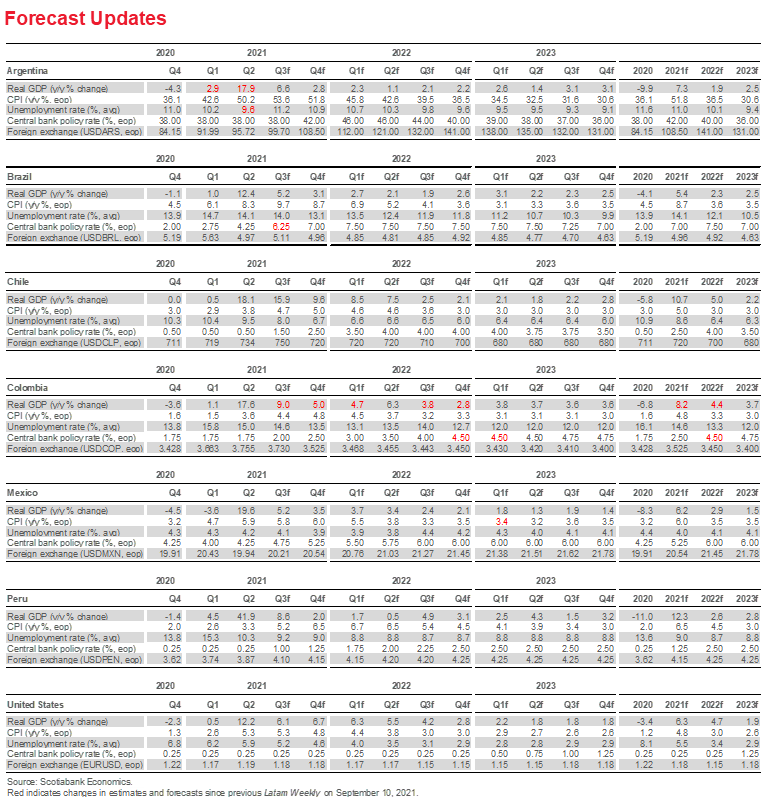

FORECAST UPDATES

- Stronger growth and higher inflation prompt forecast revisions.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

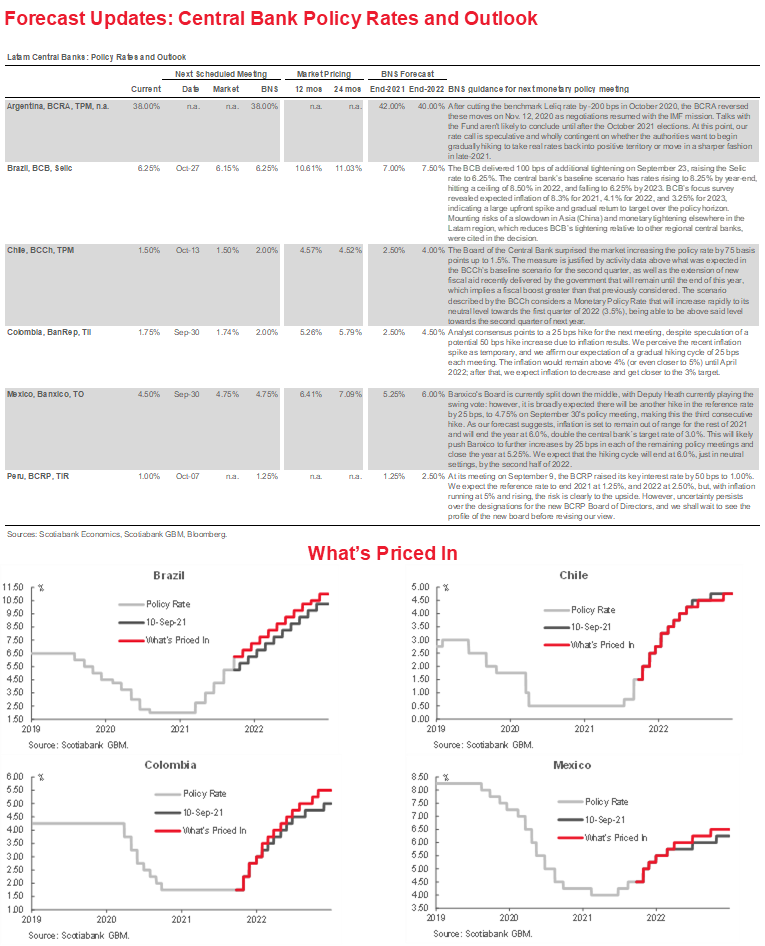

- A policy rate hike in Brazil this week is a reminder that Latam central banks are charting a “steady as she goes” course to higher rates.

- Headline inflation running above the upper bands of inflation-targeting central banks across the region focuses attention on the issue of whether temporary supply-side price shocks will spill over to expectations.

- While past episodes of above-target inflation have featured an orderly and timely return of inflation to price stability, central banks must be cognizant of possible risks that could throw them off course.

- Less favourable global financial conditions and the build of leverage in domestic public and private balance sheets are twin risks—the Scylla and Charybdis—through which central banks must pass in pursuit of their price stability at full employment objectives.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

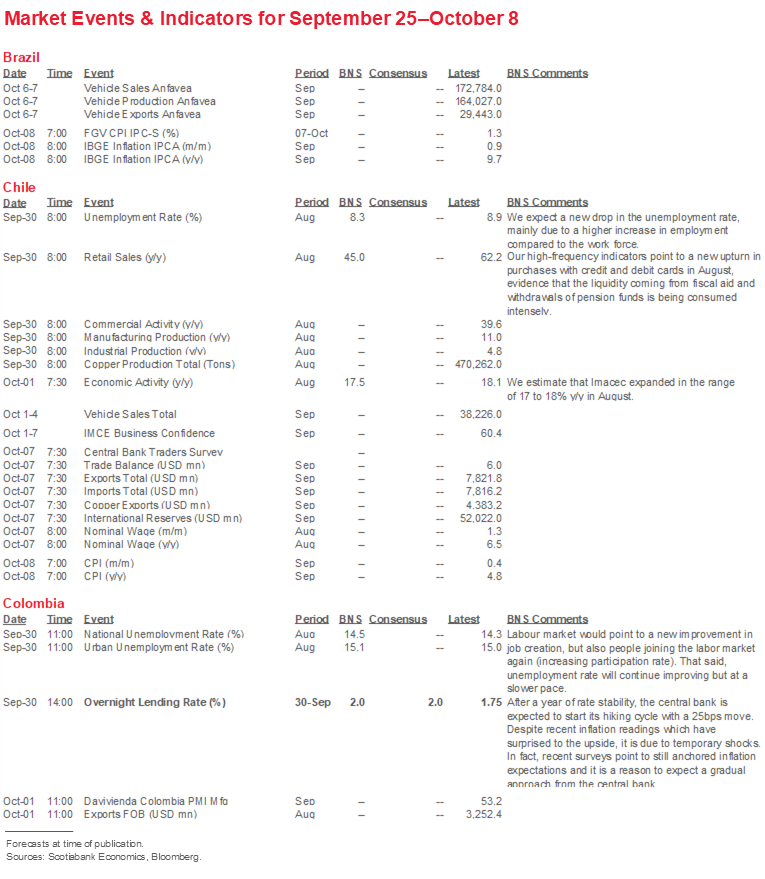

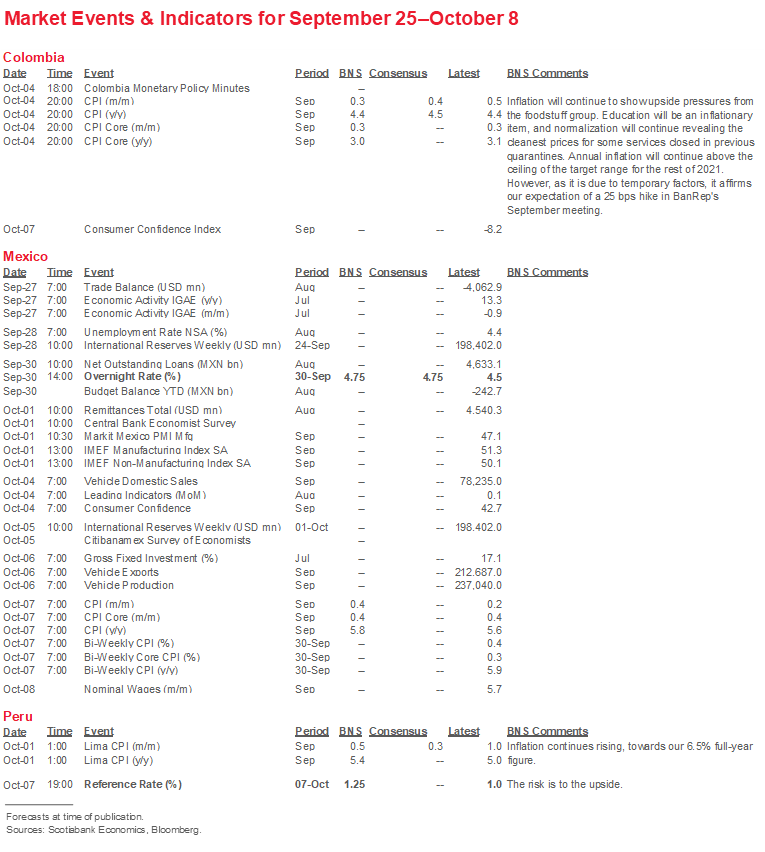

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

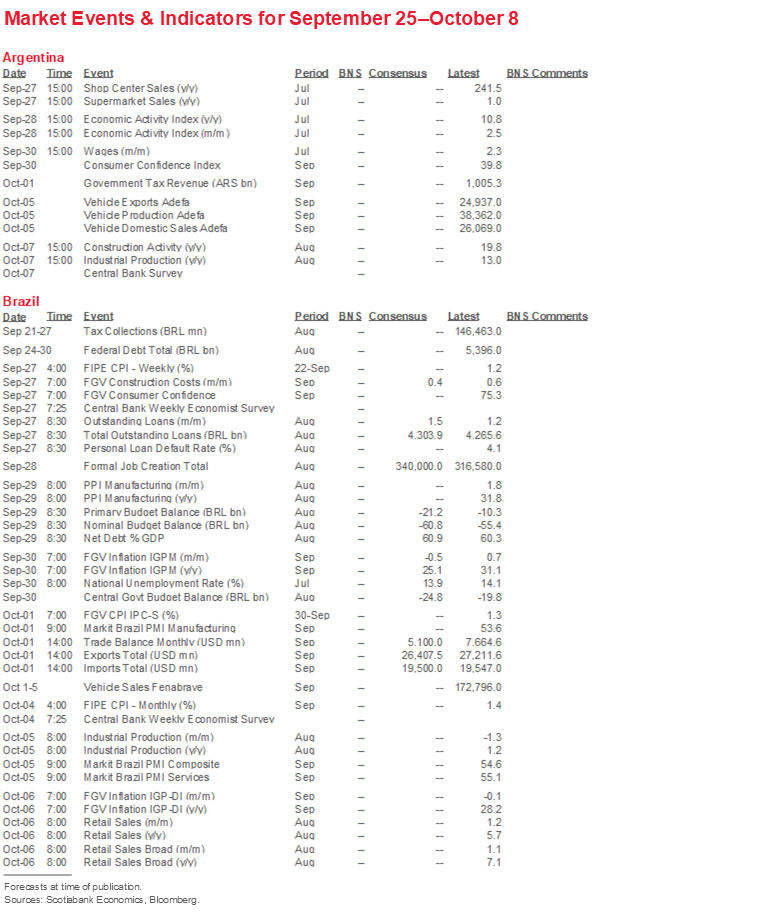

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period September 25–October 8 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: Navigating Between Scylla and Charybdis?

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Latam central banks have embarked on a tightening cycle designed to prevent temporary price shocks from becoming embedded in inflation expectations.

- Previous episodes of above-target inflation in the region suggest that these shocks do not pose insurmountable obstacles to central banks with credible inflation-targeting frameworks.

- But challenges remain. The risk of unfavourable external financial conditions, as investor risk appetite fads or global rates rise, and the possible build-up of leverage in domestic public and private balance sheets pose twin risks.

- Like Homer‘s hero, Odysseus, who had to sail between the twin perils of Scylla and Charybdis, Latam central banks may be required to navigate treacherous waters in the months ahead.

HIGHER INFLATION AND THE TWIN RISKS TO PRICE STABILITY

Latam central banks are charting a “steady as she goes” course to higher rates as they unwind the extraordinarily accommodative monetary conditions introduced to fight the economic and financial side effects of the pandemic. Inflation is tracking higher across the region and central bankers are cognizant of the need to anchor expectations. Yet, while the direction of policy rate changes over the near term is clear, the pace at which central banks are likely to raise interest rates and the challenges they may confront in their quest for long-term price stability are less apparent. Like Homer‘s hero, Odysseus, who had to sail between the twin perils of Scylla and Charybdis, Latam central banks may be required to navigate treacherous waters in the months ahead.

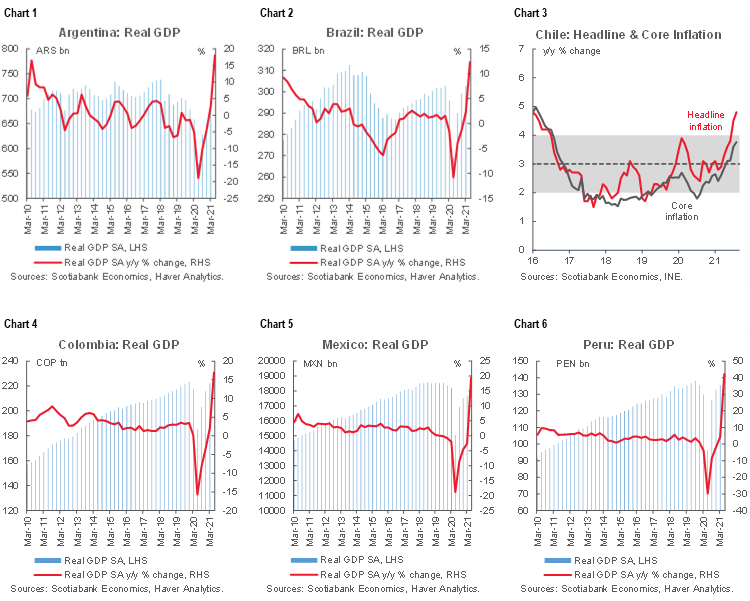

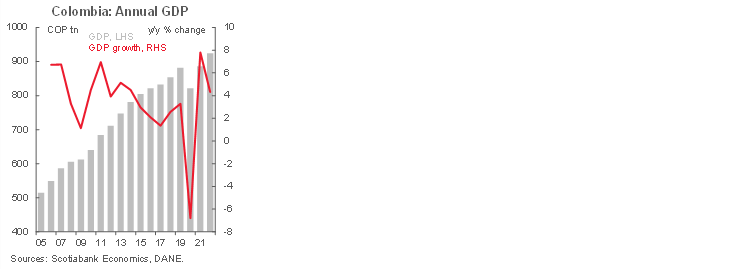

Across the Latam region economic recovery output is returning to pre-pandemic levels (charts 1–6). In Chile and Colombia, output has closed the gap.

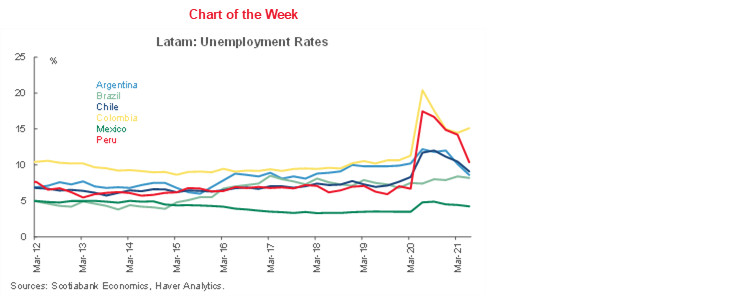

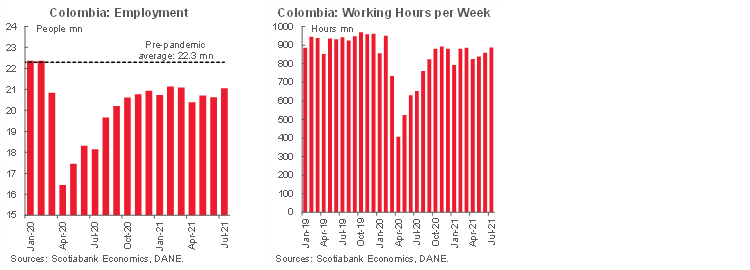

Less progress has been made in terms of labour market recovery. Despite sharp drops in a few countries, and more gradual declines in others, unemployment rates remain above March 2020 levels in most countries of the region (chart 7). The divergence in employment and output responses leads Scotiabank’s team in Bogota to examine the Okun relationship between the two (see the discussion below). Such considerations could militate for patience and slower pace in central banks’ monetary tightening cycles.

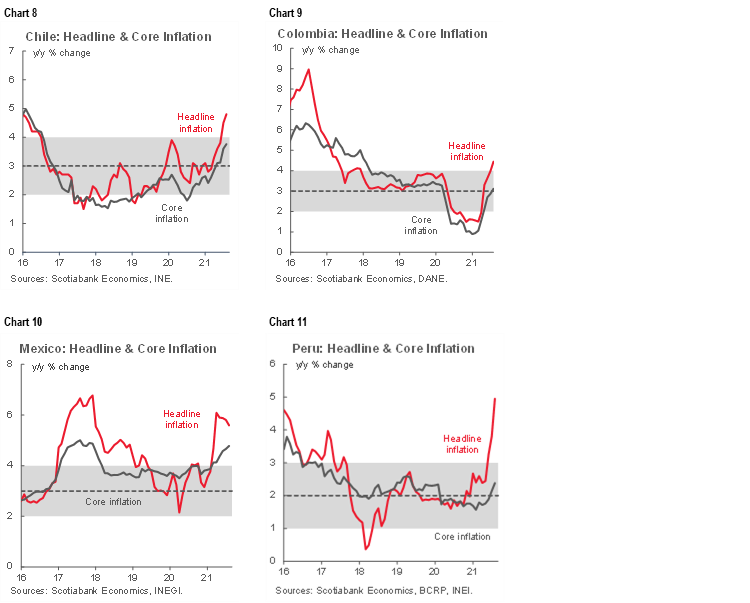

The need for tighter monetary conditions stems from inflation rates that have spiked higher, with headline inflation now above the upper bound of inflation-targeting central banks in the Pacific Alliance countries, significantly so in the case of Mexico and Peru (charts 8–11). Individual country experience varies, however, and the potential threat to expectational anchors differs across the region. In Colombia, for example, core inflation remains at the mid-point of BanRep’s target, while both headline and core inflation in Mexico have been running consistently above Banxico’s upper band. Our team in Mexico City highlight below how domestic price developments in Mexico are influenced by the nuanced evolution of the economy. In Chile, meanwhile, headline inflation is well above the BCCh’s upper bound, while core remains within the target range, though it is trending higher. Similarly, core inflation in Peru remains comfortably within the BCRP’s target bands as headline inflation has spiked.

Since core inflation is viewed as a more reliable indicator of underlying price pressures, it may provide a better guide to the risk that inflation expectations are becoming unmoored. Recent increases in core inflation across the region could thus be cause for concern. But such concerns should be weighed against previous experience.

Pacific Alliance countries have experienced temporary bouts of above-target inflation in the past. In Chile, Colombia and Peru, large currency depreciations, fueled by steep declines in global commodity prices and fears of slower growth in China, led to one such episode in 2016. Mexico experienced similar price pressures in 2017, led by higher food and energy costs exacerbated by a weaker peso and an end to government controls on gasoline and other fuels. In all cases, clear central bank communications, which supported credible inflation-target frameworks, and the calibrated tightening of monetary conditions, gradually restored inflation rates to their respective targets.

These episodes suggest that current inflation developments are not necessarily a harbinger of sustained higher inflation. However, they do underscore the importance of central banks acting in a manner consistent with their long-term price stability commitments; waiting too long or moving at too slow a pace in the face of evidence that the anchor on inflation expectations is shifting could raise the eventual costs of bringing inflation back to target. And because inflation expectations evolve over time in response to new information, possibly through a process analogous to Bayesian updating, the longer and higher that headline inflation runs above the target level without eliciting a response, the greater the risk to expectations. This effect may account for the aggressive tightening by Brazil’s BCB over the past several months, including yesterday’s 100 bp increase in the Selic rate to 6.25%.

At the same time, it would be imprudent to blithely assume that there are no hidden shoals in the “steady as goes” course to higher rates. Several risks lie in the path to long-term price stability.

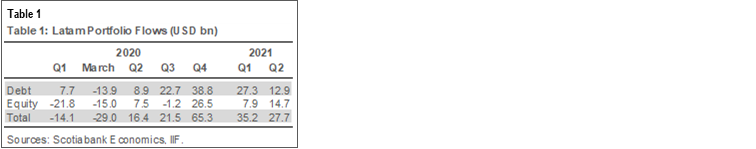

This week’s meeting of the Federal Reserve Board—which signaled the possible start of a tapering of the Fed’s bond purchases and re-focused attention on the timing of US interest rate hikes—and market tremors over financial developments in China are timely reminders that the benign external financial conditions that have prevailed could become less favourable. Unexpected increases in US interest rates or a shift in global risk appetite could trigger capital outflows. That was certainly the case with respect to the financial disruption that accompanied the onset of the global pandemic (table 1).

Latam markets experienced a sudden withdrawal of capital in March 2020 as investors sought safe havens in the face of unprecedented uncertainty. Although those outflows were quickly reversed as markets calmed and investors reassessed risks, the episode highlights the potential dangers that could lie ahead. Steep currency depreciations triggered by large outflows raise the specter of pass through effects on inflation as higher import prices on foodstuffs and key inputs feeds through into other prices. Such effects have declined over the past two decades or so as inflation-targeting regimes have gained credibility, but the 2016–17 experience shows that it remains an important consideration with respect to inflation expectations and monetary policy decisions. As the discussion by Scotiabank’s experts in Lima below highlights, such considerations may be especially relevant with respect to Peru.

The underlying state of public and private balance sheets is another consideration that central bankers will have to monitor in the weeks and months ahead. In particular, high public debt burdens reflecting extraordinary fiscal responses to the pandemic could rekindle old fears of fiscal dominance—the notion that central banks’ price stability commitments become hostage to the need to finance governments. There is no indication that is a relevant consideration across the region, except in the outlier case of Argentina; indeed, Pacific Alliance governments have introduced reforms to strengthen public finances (as in the case of Colombia) or laid out plans to bring deficits down and ensure fiscal sustainability. Nevertheless, unexpected fiscal shocks overlaid on elevated public debt burdens could cause foreign and domestic investors to reassess possible risks.

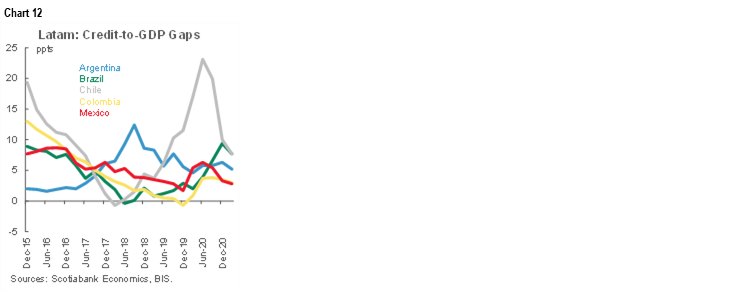

Private non-financial sector balance sheets are also a potential concern. The low interest environment that followed the global financial crisis animated a build-up of leverage in private sector balance sheets globally. One way to assess this build-up is to look at credit-to-output gaps that measure the extent to which increases in credit outpace the underlying growth in GDP. While there is no reason to believe that credit and output should grow in lock step year-in, year-out, persistent increases in credit that outpace GDP (on which debt servicing capacity rests) could be an early warning indicator of possible problems. In this respect, there is some evidence of such gaps across the Latam region over the past decade, though such effects have moderated more recently (chart 12).

For non-financial firms and households, this increase in leverage entails greater risks. This is because the higher the degree of leverage, the greater the likelihood that a subsequent deleveraging in response to an interest rate or output shock becomes highly disruptive. In effect, leverage serves as an amplifier of adverse shocks. Work done by the IMF staff suggests that higher leverage tends to be associated with more subdued economic activity over the subsequent 12 quarters in both advanced and emerging economies. For central banks navigating their way to price stability at full employment, the presence of such effects could represent an additional challenge. Here, again, there is no clear and present danger associated with leveraged private sector balance sheets. But the potential for disruptive deleveraging, should it become necessary, could represent a possible constraint on the pace of monetary tightening.

Possible external challenges emanating from shifts in investor risk appetite or disruption in Chinese financial markets that spills over to global markets and the leveraging of domestic public and private balance sheets constitute twin risks—the Scylla and Charybdis—central banks may confront. Banks with robust inflation-targeting frameworks, and that are widely viewed as credible, supported by governments with clear fiscal anchors, are better equipped to find their way through the narrows.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Government Presents 2022 Budget Bill Amid Low Number of COVID-19 Cases

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

56.2.2939.1495 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

The number of confirmed daily cases of COVID-19 has slightly increased in recent days, although it remains at its lowest level since April 2020. Similarly, the positivity rate is at the lowest level since the beginning of the pandemic, at around 1%, and COVID-19-related deaths continue to decrease. Vaccination has reached 88% of the target population, while the occupancy of ICU beds continues to decrease in all age groups. Thanks to these developments, mobility has increased, reaching—or surpassing for some activities—pre-pandemic levels. As of September 22, no commune is in lockdown, while more than 98% of the population has reached the highest degree of mobility in the “Paso a Paso” Plan.

In preparation for the budget bill, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) released the results of its consultancy of economists on long-term GDP and copper price forecasts on Monday, September 13. According to the MoF, estimated long-term GDP growth increased from 1.6% to 2.6% for 2022, while the estimated long-term copper price increased from USD 2.88 per pound to USD 3.31 per pound for the next 10 years. Both measures are key variables underlying the fiscal budget.

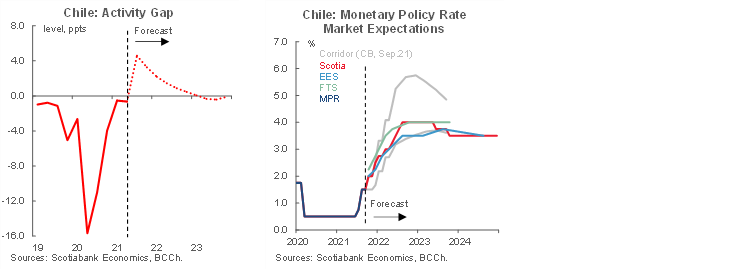

On Wednesday, September 15, the central bank (BCCh) released the Minutes of its last Monetary Policy Meeting in which the Board decided to increase the Monetary Policy Rate 75 basis points (bps). According to the Minutes, a critical argument behind the decision was that the current degree of monetary stimulus was not commensurate with an economy that grew at double-digit rates and that had already closed the activity gap (first chart). Given this argument, the BCCh will probably consider rate hikes of between 50–75 bps in October and December. In this regard, the BCCh’s baseline scenario reveals a Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) that will increase rapidly to its neutral level towards the first quarter of 2022 (3.5%), rising above this level towards the second quarter of next year (second chart).

Our high-frequency indicators show a high level of purchases with credit and debit cards up to the second week of September, evidence that the liquidity coming from fiscal aid and withdrawals of pension funds is fueling consumption. Restaurants, tourism and travel services continue to benefit from high liquidity, showing further increases due to greater mobility and reopening of the economy.

In the fortnight ahead, on September 30, the INE will release the unemployment rate for the moving quarter that ended in August, as well as the indicators by economic sectors for August. On October 1, the BCCh will publish the monthly GDP growth for August. Also, it is expected that the government will present its 2022 Fiscal Budget to Congress, no later than September 30. Finally, on October 8, the INE will publish the CPI index for September.

Colombia—Between Positive Surprises and Challenges Ahead

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

A year and a half has passed since the COVID-19 outbreak shook Colombia. Quarantines introduced to control the virus hit the economy hard. And, at the beginning of the pandemic, the possibility of returning to pre-pandemic production levels seemed far off. However, despite the strong impact of the COVID-19 shock, the economy showed resilience and some traditional activities strengthened during the pandemic. Meanwhile, new activities led growth. In this respect, news about the economic recovery consistently surprised us and market consensus since the economy keeps improving, despite the third COVID-19 wave and in a context of significant social discontent.

According to the most recent DANE release, economic activity in July reached pre-pandemic levels (first chart). It is noteworthy that the services-related sector had the strongest performance, even with some activities still operating under capacity. The strong pace of economic activity leads us to revise up our GDP forecast. We now expect an expansion of 8.2% in 2021 and 4.4% in 2022 (chart 1).

However, Okun’s Law doesn't seem to be working very well; in fact, despite the strong recovery in the economy, employment remains 5.5% below pre-pandemic levels (second chart). How employment is measured may explain the gap between the recoveries in output and employment. If we measure employment by the average of hours worked per week, the lag versus pre-pandemic is lower than the gap if we measure the employment in terms of persons (third chart). Either way, employment policies remain a key item on the political agenda as the youth population demanded in the previous strike for increasing job opportunities.

On the external sector side, there are two effects at work: widening trade deficits, which are to be expected in an economic recovery; and higher international prices on raw material imports. Accordingly, as we revised our GDP growth forecast, we also revised the current account deficit forecast for 2021 from 4.0% to 5.2% of GDP. On the financing side, Colombia will remain dependent on government debt issues, with FDI contributing more in the second half of the year.

In the short-term, inflation will likely track close to 5%, although we think that the current price shock is temporary. However, as we explained in the previous Latam Weekly, prices dynamics are sufficiently concerning to motivate a hawkish bias in the central bank’s hiking cycle. That said, we expect a 25 bp rate hike in each possible meeting in 2021 and 2022, as reflected in our revised forecast of the monetary policy rate for Dec-2022 of 4.50%, up from 4.0%. At that point, we expect the Colombian economy to consolidate better growth numbers with inflation hovering around the 3%.

Challenges remain, however. Although the economy is recovering faster than expected, the coming months may see increased uncertainty from the electoral cycle. Presidential campaigns will soon begin their most intense phase ahead of the May 29, 2022 vote. Before that, legislative elections take place on March 13, 2022. And while the traditional parties have not yet revealed their potential strategies, we expect alliances to become clearer. For now, recent surveys suggest that voters are undecided, the menu of presidential candidates is crowded, and the key months are still to come.

Mexico—Mexican Regional and Sectoral Dynamics, and Monetary Policy

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

There are arguments for caution on rate hikes, but we think the balance of risks favours being prudent on controlling inflation—recent data continue to support the unwinding of monetary stimulus through further interest rate increases.

Banxico’s Board is currently split down the middle. On one end, Governor Diaz de Leon and Deputy Espinoza are entrenched in the hawkish camp that is delivering rate hikes to keep inflation in check. On the opposite end, Deputies Esquivel and Borja are in the dovish camp, arguing that the inflationary shock the country is facing is supply-side driven, and not of the kind that monetary policy can efficiently deal with. Hovering somewhere in between we have Deputy Heath, currently playing the role of swing voter. Which camp is correct?

We have argued in the past that raising the policy rate to 6.0% by the end of 2022, as both markets and economists anticipate, would only move monetary conditions to neutral. In fact, Banxico’s own estimate of neutral real rates and consensus estimates of long-run inflation suggest 6% is a neutral setting. At the same time, Banxico’s latest Quarterly Inflation Report suggests that by the end of 2022 the output gap will be within 50 bps of being closed in its central-scenario (page 101 here), and inflation will be 20 bps above the midpoint of its target—essentially, that the economy will be operating at levels that justify “neutral settings”.

In this context, there are two considerations that, in our view, support erring on the hawkish side. The first consideration is “plain vanilla”—the traditional monetary policy transmission lag of 12-18 months, which means that with the economy operating in its sweet spot by the end of 2022, neutral monetary policy would arrive a year too late. We acknowledge, however, that this argument is weakened in a world in which most developed markets are likely to keep conditions lax, giving the emerging economies somewhat of a pass on this front, through relative monetary conditions that removes potential inflationary pressures coming from currency depreciation.

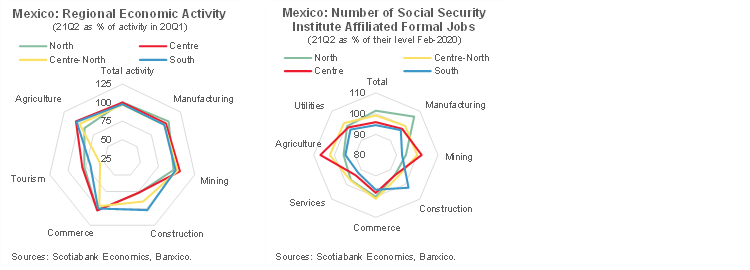

The second consideration, which in our view may be more important, comes from the nuanced evolution of the domestic economy. It is true that not all sectors in an economy return to potential or full capacity at the same pace, leading to possible supply shortages of key inputs. But price pressures in a complex and integrated supply chain—or within a more economically complex region—can generate more distortions and confusion with respect to overall output and prices than a marginal sector or region. It is worth noting, therefore, that strategic sectors such as manufacturing and more economically complex regions of the country—such as the North and the Bajio—are much further along in their recovery process than sectors with less complex supply chains and regions, such as tourism and the South (first and second charts). This observation weakens the dovish camp argument that supply-side shocks are driving the increase in inflation. Moreover, outside the South of the country, formal employment in most sectors is now above pre-pandemic levels. With this in mind, we think price pressures are not only the result of input shortages and commodity price reflation but are also fueled by underlying growth.

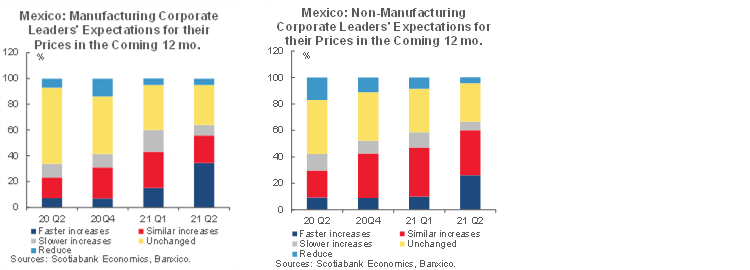

In this context, we think it highly relevant that in a survey published last week by Banxico in its Report on Regional Economies a majority of company executives in both the manufacturing (third 3) and non-manufacturing (fourth chart) sector expected to increase their prices over the next 12 months at the current or faster pace (55.7% and 60.1%, respectively). In our view, this reflects contamination of prices, as well as an increase in pricing power for firms that have been dealing with a contracting economy for the past two years. In industries with tight supply chains, in which firms have faced two years of flat or negative growth, demand is picking up fast, and firms are experiencing faster producer price increases (PPI inflation in Mexico started rapidly accelerating in the summer of 2020); it is not a surprise that companies plan to increase prices.

Peru—Two Months into the Castillo Regime: Cohesion on Economic Management, but Elsewhere Confusion Abounds

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Mario Guerrero, Deputy Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6000 Ext. 16557 (Peru)

mario.guerrero@scotiabank.com.pe

It’s been nearly two months now since the new Castillo regime came to power in late July. Over this time, we’ve been able to sketch a better picture of the government. And yet, it’s still only a sketch. The government has provided more clarity and cohesion on its economic agenda. The budget proposal for 2022, the guidelines established in the Multi-year Macroeconomic Framework (Marco Macroeconómico Multianual), the signals given by Finance Minister Pedro Francke, and even the recent interventions by President Castillo in his visit this week to the U.N. and World Bank, are all within the bounds of reasonable policy, and proper fiscal deficit and debt management. The leftist bent of government policy resides mainly in two issues that are not really that radical in the context of Peruvian politics: a greater emphasis on social programs, and the likelihood of an increase in taxation, at least for mining. If anything, during his trip abroad, Castillo has added a new pro-business element to the administration’s economic posturing, seeking to attract foreign private investment to Peru.

It’s in the government’s non-economic issues agenda where signals have been more mixed, affecting business confidence and generating further uncertainty. For example, the government party, Perú Libre, has begun to undertake serious endeavours to obtain signatures in favor of a referendum on a Constitutional Assembly and reform. There are also conflicting views among key figures of the administration, including the Head of the Cabinet, Guido Bellido, regarding the government’s position on recognizing Venezuela. This dispute has already been aired through social media and the public spat could escalate further, possibly affecting the make up of the Cabinet upon Castillo’s return to Lima from the US. Whether or not it has an impact on the Cabinet, the incident generates additional uncertainty as to how the administration and the ruling party make decisions on key issues.

At the same time, the President of the Board of the BCRP, Julio Velarde, has yet to be ratified, and the delay is raising questions regarding whether other options are being weighed.

Meanwhile, short-term economic concerns are evolving. While recent figures continue to point to healthy growth and improving fiscal and external macro accounts, concern is shifting to inflation, FX volatility, capital outflows and the outlook for private investment.

The third quarter started out with robust GDP growth of 12.9% y/y in July. This represented 0.4% growth versus pre-lockdown July 2019 levels, and 0.2% in month-on-month terms. It is also in line with our full-year 12.3% forecast. The BCRP raised its forecast, in its quarterly inflation report, from 10.7% GDP growth for 2021 to 11.9%, drawing nearer to our own.

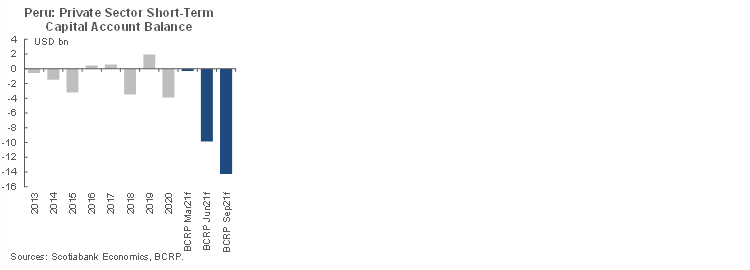

Overall, there is still little evidence that political turbulence is having much of an impact on growth. The same cannot be said for some of the financial indicators. The most dramatic is the outflow of short-term capital (first chart). The BCRP now expects a huge USD 14.3 bn of short-term capital outflow in 2021. This is up from its previous forecast of USD 9.9 bn, and from the forecast at the beginning of the year, which was barely USD 300 mn. The BCRP may fall short yet again, as the outflow in the first half of the year was USD 13 bn. The figure is over triple the previous record outflow.

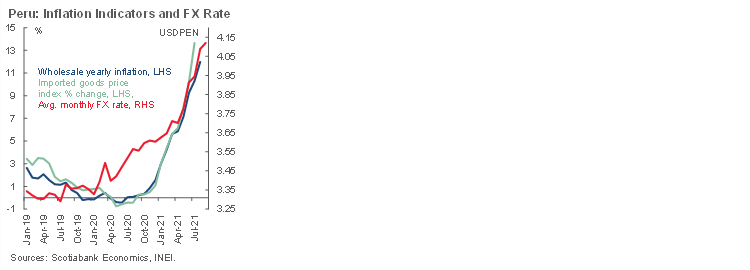

The PEN has also continued weakening, reaching a new all-time high at 4.12 during the week (second chart). The pace of the depreciation has slowed a bit, but domestic corporate demand for USD continues to put pressure on the currency. Meanwhile, offshore movements and pension funds have become much more neutral.

Inflation is becoming an increasing concern. With yearly inflation to August rising to 5.0%, the BCRP needed to increase its forecast for 2021, which it did, from 3.0% to 4.9%, well above its target range (second chart again). The BCRP expects inflation to fall back to 2.6% in 2022, arguing the following: 1. Inflation is temporary; 2. The offshore components that are driving inflation are stabilizing; and 3. Inflation expectations (currently at 3.07%), while rising, are not overly worrisome. The BCRP underlines that core inflation is at 3.0% yearly to August, and has, therefore, not breached the target ceiling.

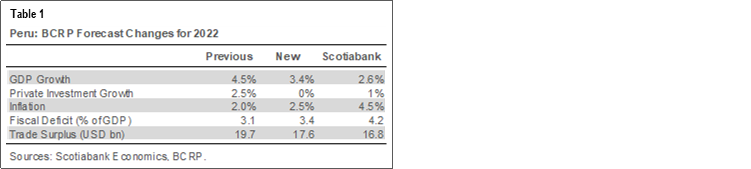

All this suggests that the BCRP is uncomfortable with the idea of adopting an aggressive reduction in monetary stimulus going forward. However, in practice, the BCRP has been taking its policy decisions based on the data as it has become available, raising the reference rate, not so much in anticipation of rising inflation going forward, but in reaction to recent past inflation data as it has emerged. Given that we expect inflation to rise at a greater pace than the BCRP (4.5% in 2022, versus 2.6% for the BCRP), we believe the BCRP will continue raising its reference rate, to at least 2.5% in 2022, if not more (table 1).

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.