FORECAST UPDATES

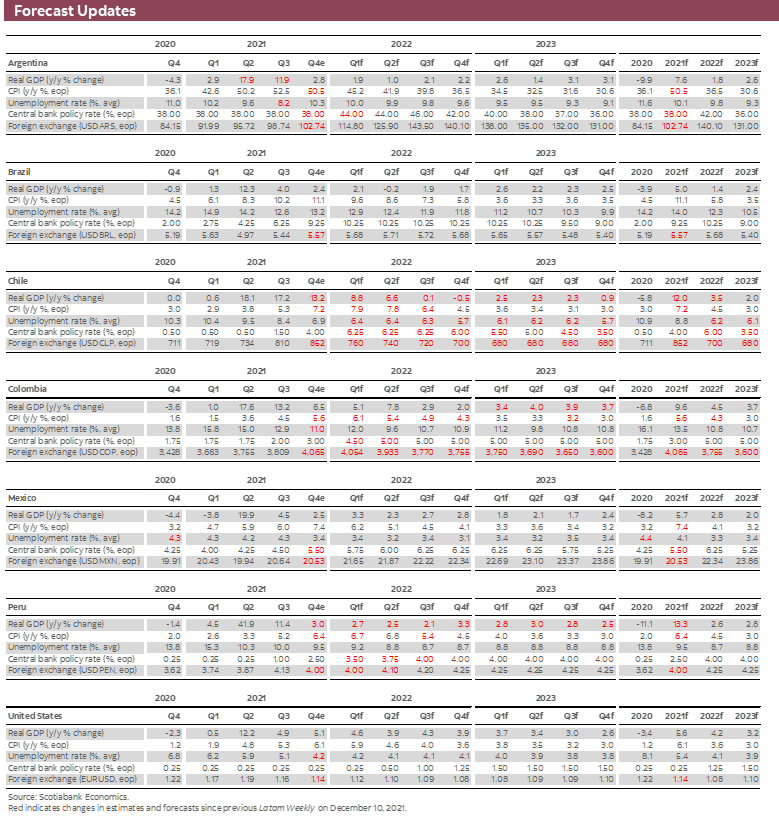

- Rising COVID-19 caseloads from the omicron variant increase the uncertainty with respect to short-term forecasts. For now, however, Scotiabank teams in the Latam region do not anticipate large revisions; recent changes reflect new data and not a change in view. See the full set of projections in the forecast table below.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- As the new year begins, rising COVID-19 caseloads from the omicron variant reanimate concerns that another wave of the pandemic could set back economic recovery.

- Prior to the latest developments, Latam economies posted strong recoveries in 2021, with most countries back to, or above, pre-pandemic output levels. Strong growth has been accompanied by high inflation, however, with supply bottlenecks and supply chain disruptions adding to price pressures.

- Preliminary indications across the region suggest that the economic effects of the latest wave of infections could be contained, notwithstanding the highly-transmissible nature of the omicron variant.

- Nevertheless, even in that felicitous scenario, an old challenge of raising long-term growth in the region remains. Addressing that challenge should be a key policy priority for policy makers.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

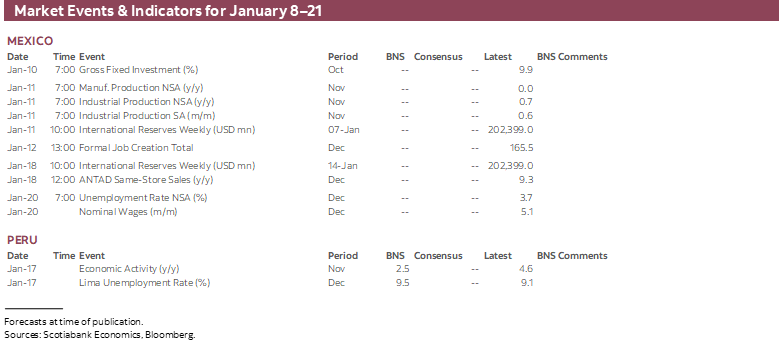

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period January 8–21 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: New Year, Old Challenges?

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- The emergence and rapid transmission of the omicron variant introduces additional uncertainty to the economic outlook.

- There are grounds for cautious optimism that the economic effects on the Latam region will be limited: while highly infectious, resulting in a sudden spike in cases, the latest variant of the COVID-19 virus appears to be less virulent. At the same time, economies in the region and around the globe may have “learned to live” with COVID, as behaviours change to sustain economic activity while adhering to public health restrictions.

- That outcome would certainly be welcomed. But even if that is the case, policy makers across the region face growing demands to address long-standing social problems the pandemic has highlighted.

- Raising long-term growth rates, building on earlier market liberalization reforms, is necessary to address this old challenge.

IT’S DÉJÀ VU ALL OVER AGAIN

Welcome to 2022, or is it 2020 all over again? As the new year begins, the spread of the omicron variant of COVID-19 casts a pall over the global economy. Dramatic spikes in caseloads have triggered enhanced social distancing and, in some countries, lockdowns. The re-introduction of these measures, meanwhile, has rekindled painful memories of early 2020, when the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic. In the words of the great American social philosopher, Yogi Berra, “it's déjà vu all over again.”

Risks to the economy come from two fronts. The first risk, clearly, is a shock to economic activity from widespread lockdowns. The impact of this effect may be contained, however, as economies around the globe have “learned to live with lockdowns,” devising means to sustain activity while adhering to public health protocols. The second risk is a continuation and deepening of supply chain problems. This effect could extend the inflation shock that central banks across the region have been fighting, with greater threats to inflation anchors, requiring more aggressive tightening actions.

Hopefully, the latest twist in the ongoing pandemic saga will be short-lived and the economic costs well contained. To this point at least, there are grounds for cautious optimism. Data from South Africa suggests that the economic implications from the omicron wave that is now cresting in other countries could be limited. While far more transmissible, leading to vertiginous increases in case counts, the latest variant seems to be less virulent, resulting in fewer hospitalizations and deaths. The South African experience suggests that omicron outbreaks peak rapidly, but crash equally quickly. The same pattern seems to be playing out elsewhere.

Should those trends continue, it is possible that the implications for growth prospects will indeed be limited. In that event, the new challenge posed by omicron may have fewer consequences than the initial outbreak, and the public health policy responses to it, had on the economy.

That would be welcomed news with which to start the new year. Across the Latam region, countries staged impressive recoveries in 2021, with output returning to pre-pandemic levels in most. And looking ahead, Scotiabank economists see robust—albeit lower—growth continuing into 2022 and beyond (see forecast table above). If global growth continues unimpeded, with recovery progressing in advanced countries, generating export opportunities, a favourable external environment should support this outlook.

At the same time, there are important caveats that temper the case for optimism. Most important, the omicron outbreak in South Africa occurred during springtime in the Southern Hemisphere, which facilitates social distancing, and the South African population is relatively young, with high rates of previous COVID-19 infection. Interestingly, Latam countries share these characteristics. Most advanced countries, however, do not; hence the need for caution. Early indications from the Latam region suggest that, while cases have spiked dramatically with the spread of the omicron variant, hospitalization and deaths have not (see the discussion in the country notes section below).

But, even while Latam growth rates (as opposed to levels) are expected to return to pre-pandemic levels going forward, a critical challenge remains. This is the “old challenge” alluded to in the title of needing to raise potential growth rates in order to boost per capita incomes given the region's higher rate of population growth and address the high level of inequality that has long characterized the Latam region. Just as questions linger over the fate of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which languishes in Congress, the challenge for the Latam region is to build back better by raising long-term growth.

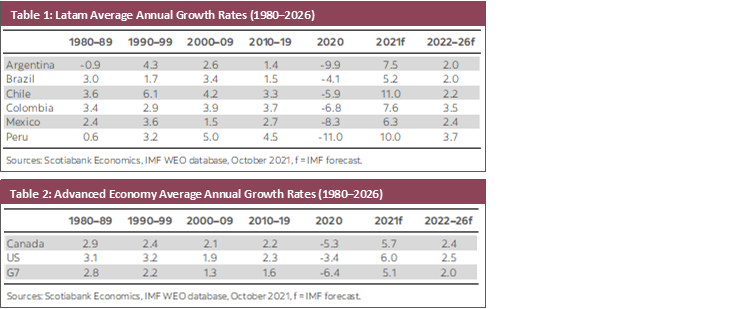

Examining growth rates over a long-term period (table 1) provides some perspective on the challenge. For most countries, the average annual growth rate in the decade preceding the COVID-19 event was below that in the 2000–09 period (Mexico is the sole exception.) To some extent, this reflects the fact that the 2010s were a decade of desultory growth worldwide, as economies recovered from the global financial crisis. More troubling, perhaps, is the fact that IMF medium-term forecasts (2022–26) excluding the collapse of output in 2020 and the rebound in 2021 are generally below growth rates in earlier decades, including the 1990–99 period, and also below projected growth rates in the advanced economies (table 2).

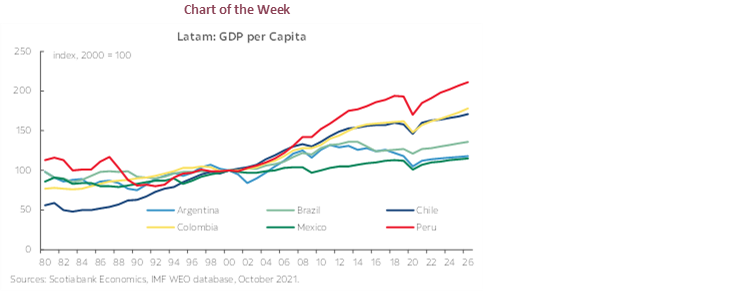

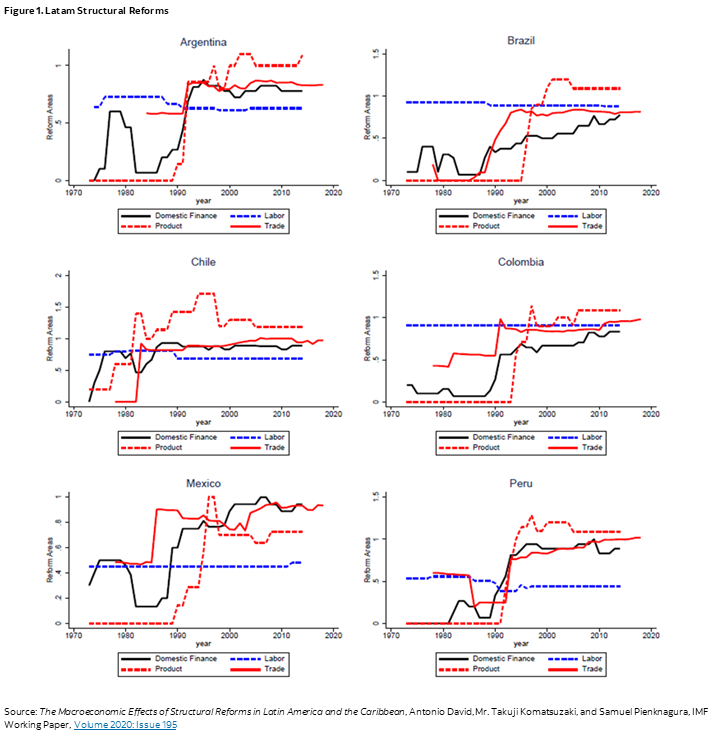

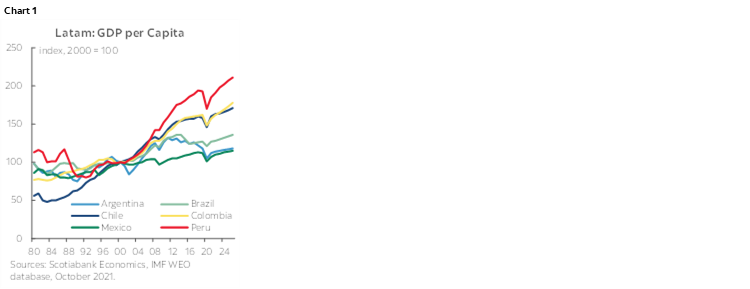

For most Latam countries, the 1990s was an important era of growth. It featured an unprecedented wave of structural reforms (Figure 1, see below) that liberalized economies and fostered robust expansion. While some of that growth can be attributed to the recovery from the “lost decade” of the 1980s, there is little debate that structural reforms facilitated the reallocation of resources from low-productivity activities to high-productivity activities and enhanced growth prospects in the region. That progress is evident in the data on GDP per capita (chart 1), which picked up after 2000. (Chile, which implemented reforms earlier, led other Latam countries in this respect.) Not all countries have reaped the same benefits from reforms, however, with most Pacific Alliance countries outperforming other regional partners.

By the end of the 1990s and the early 2000s, financial crises in the region and around the globe interrupted that progress and led to procyclical policy responses in the region.

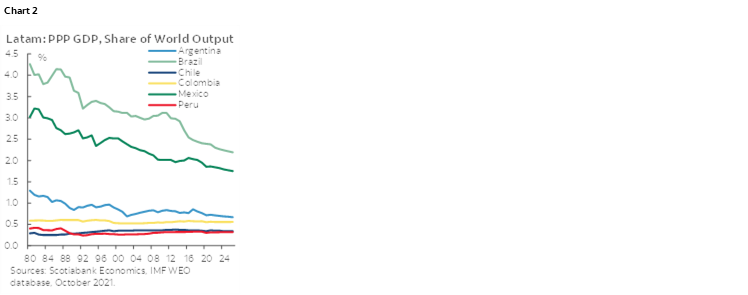

The region was less exposed to the financial dysfunction propagated by the financial excesses in advanced economies, which erupted in the subprime crisis in 2007, while strengthened policy frameworks allowed counter-cyclical policy responses that partially offset the effects of the crisis. Nevertheless, the sharp contraction in advanced economies led to the loss of external demand and worsened the region’s terms of trade, taking a toll on Latam growth. That said, external factors do not account for the fact that the region hasn’t increased its share of global GDP measured in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms (chart 2).

In this respect, while some slowing of growth would be expected over time as part of the process of convergence, as capital/labour ratios in the region converge on those of advanced economies, that isn’t what seems to be transpiring. But here, too, there are clear differences across the region: most Pacific Alliance countries have maintained their share of global GDP in PPP terms; Argentina, Brazil and Mexico have seen their share of world output decline.

The conclusion seems to be that while earlier market liberalization reforms had important growth-enhancing effects, particularly in Chile, Colombia, and Peru, those benefits are not assured or necessarily self-sustaining. Identifying the “next generation” of reforms needed to further development is thus the overarching challenge of the new year.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Omicron Advances in Chile, One Month after the First Case of the New Variant

Jorge Selaive, Head Economist, Chile

+56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

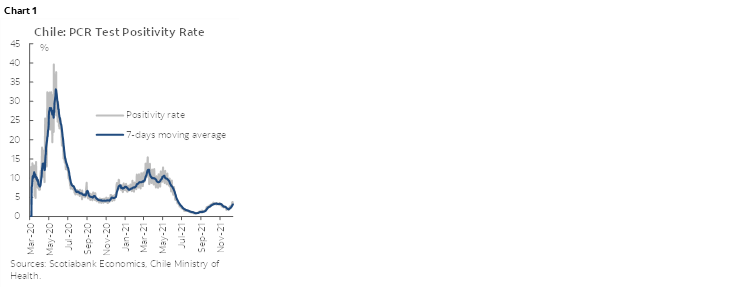

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has continued to rise in recent days but at a slower pace. The positivity rate reached 3.1% in the last week (chart 1), and the vaccination campaign reached 92.1% of the eligible population. The occupancy of ICU beds and the COVID-19-related death rates increased but remain at low levels. Meanwhile, the rollout of booster (third) doses keeps moving forward, reaching 10.7 million people. In recent days, the government announced the availability of a new booster dose (fourth) beginning in January. In the last few days, the Chilean Ministry of Health reported 690 COVID-19 cases in total, with no increase in ICU occupancy resulting from the new omicron variant. It should be noted that omicron has been present in Chile since December 4, 2021.

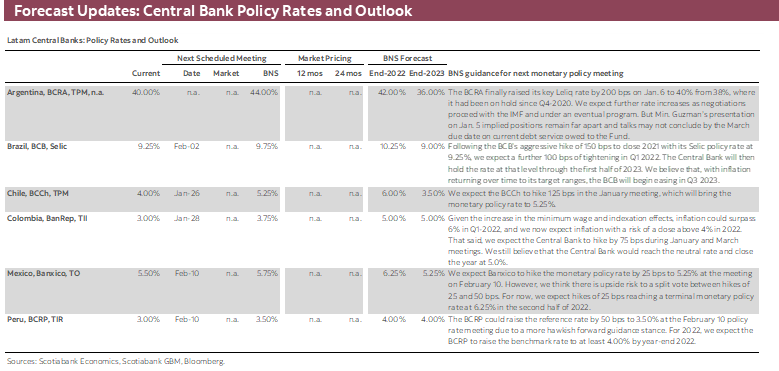

Regarding the economic indicators, on Tuesday December 14, the central bank (BCCh) increased the Monetary Policy Rate by 125 basis points (bps) to 4%, in line with our expectations. In our view, the decision to increase the rate by 125 bps signaled an intention to place the rate above its nominal neutral level as soon as possible. We expect a path towards normalization with a 125 bps increase at the January meeting to reach a rate of 5.25%.

On Wednesday December 15, the BCCh released its quarterly Monetary Policy Report, which included updated forecasts for key macroeconomic indicators. In this Report, the central bank anticipates a GDP expansion of 11.8% for 2021 (range between 11.5% and 12%), in view of the strong performance of economic activity in recent months. For 2022, the BCCh slightly increased its projection to 2.0% (range between 1.5% and 2.5%), which includes a contraction in both total investment and consumption. The BCCh’s baseline scenario includes a technical recession in 2022, a view that we share in Scotiabank.

Early in 2022, on Monday, January 3, the BCCh released November’s economic activity index (IMACEC), which expanded 14.3% y/y, above both our and market expectations. In seasonally adjusted figures, the IMACEC increased 0.3% m/m, mainly explained by increases in services (1.8% m/m), with decreases in output in the rest of the industries. Fiscal expenditure increased 57% y/y in November in real terms, driven by direct transfers (Universal Emergency Family Income) and public consumption, giving support to economic activity. With those figures, we forecast an expansion of around 12% in the GDP for 2021.

As well, on Friday, December 31, statistical agency INE released the unemployment rate for the quarter that ended in November, which fell to 7.5%. The labour market continued to show signs of improvement, creating 102k new jobs compared to the last quarter. Overall, the employment gap compared to its pre-COVID-19 level fell to 505k.

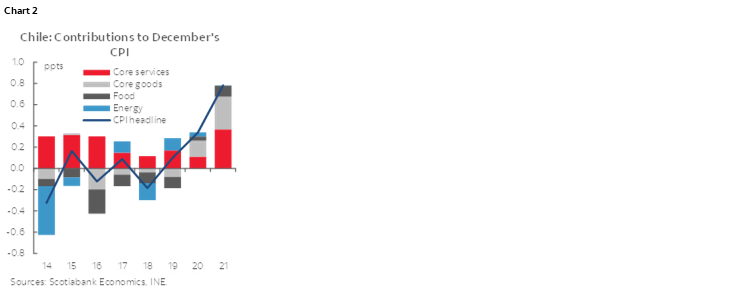

Finally, CPI increased 0.8 m/m, above both our and market expectations (Scotia: 0.54% m/m). The figures showed broad increases in the basket, explained by rises in both core goods and services, and expected increases in foods, especially meats and non-perishable foods. With this, annual inflation reached 7.2% y/y (chart 2).

In the political arena, on Sunday December 19, the leftist candidate Gabriel Boric won the presidential election against the right-wing candidate, José Antonio Kast. With a solid majority having won 55.9% of votes, Mr. Boric will become the next President of Chile, taking office in March 2022. According to the Electoral Service (Servel), there was a significant increase in turnout, especially in the lower-income districts. In this context, participation reached 55.6%—8.3 million people—a historical record since voting was made voluntary.

In addition, on Wednesday January 5, the Constitutional Assembly elected Maria Elisa Quinteros as its President and Gaspar Dominguez as Vice President. Quinteros won the vote with the support of representatives of the communist party and other left-wing social groups. The new president will replace Elisa Loncón, who ended her mandate.

In Chile, there are no macroeconomic indicators in the fortnight ahead. However, in Congress, the agenda includes the discussion of the Universal Guaranteed Pension bill, sent by the government in early December. On Monday, January 3, the Lower House floor approved the bill unanimously.

Colombia—How 2021 Ended and What to Monitor at the Beginning of 2022

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9166 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9400 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

2021 was a positive year for Colombia in terms of economic recovery, despite the negative events in May–June due to the widespread social protests. The “back to normal” mandate that began in June led the economy to a rapid recovery, surpassing pre-pandemic levels by the end of Q3-2021. Tax collection improved with the economic recovery and the MoF said that Colombia would close 2021 with a fiscal deficit of 7.6% of GDP, lower than initially expected (8.6% of GDP). However, upside pressures to inflation started to emerge in May, and inflation closed 2021 above the ceiling of the central bank’s target range (between 2% and 4%). In response to rising inflation, BanRep started its hiking cycle in September followed by an atypical and accelerated pace of 50 bps hikes in October and December in response to the speed of economic recovery and inflation pressures.

THREE TOPICS WILL LEAD THE MACRO AGENDA IN H1-2022:

1. Inflation and monetary policy

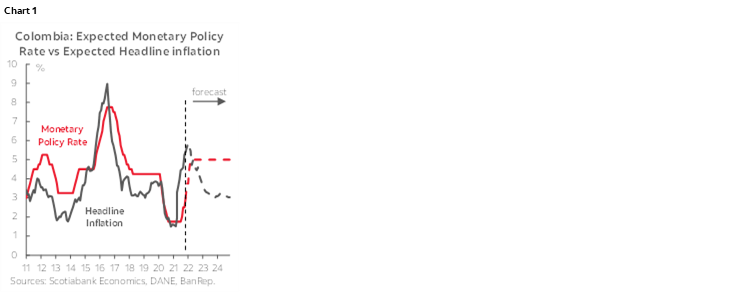

After the 2022 minimum wage increase of 10.07% (well above of the traditional rule of inflation + total productivity, which in the base case would point to a 7% increase), key prices started to be indexed and in January significant price increases were announced. As a consequence, inflation is likely to hover at or even surpass 6% in Q1-2022, and there is now a high probability that inflation will remain above 4% by December 2022. Given that, we expect the central bank to increase the policy rate by 75 bps in the January 28 meeting and again at the March 31 meeting. For now, we are not revising the terminal rate, since inflation is expected to moderate beginning in April and inflation expectations could fall to around 3%–3.5% (chart 1), such that the central bank would not exceed the neutral real rate of 1.5%. However, if a new shock arises, the scenario would change.

2. Fiscal news

At the end of 2021, Finance Minister Restrepo anticipated that fiscal results were stronger than expected, with a fiscal deficit 1% of GDP below the 8.6% of GDP estimated at the beginning of the year. In 2022, potential positive news would come with the Financial Plan, which eventually would show lower debt auctions levels. Regardless, while Colombia is not expected to recover investment grade in 2022, positive fiscal outcomes would at least assuage short-term fiscal concerns.

3. Congressional and presidential elections

January marks the start of a busy election cycle; the first milestone will be the Congressional election on March 13. We expect a Congress still dominated by market-friendly parties. However, in parallel with the Congressional vote, the main coalitions—Pacto Histórico, joined by Gustavo Petro, Equipo por Colombia (considered the centre-right coalition) and Centro-Esperanza (considered the centre-left coalition)—will make the “Consultas” to decide who is going to be the official candidate ahead of the presidential elections.

Monitoring the potential composition of Congress and the machinations behind shifting political coalitions will be critical in H1-2022. The presidential election will be held on May 19 and a potential runoff one month later (June 19). We think that strong institutions in Colombia will prevail as there are three powers in Colombia: Presidency, Congress and Courts, which in any case control key political decisions in the country.

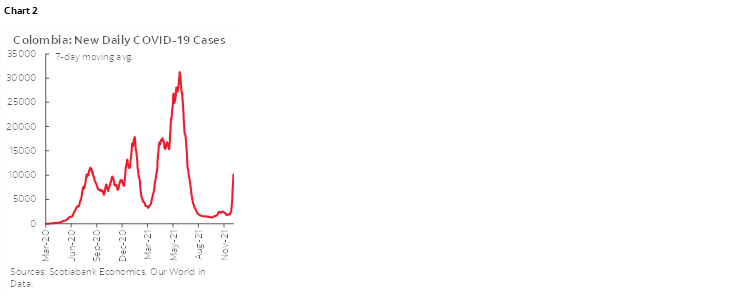

What is happening with Omicron?

After the strong third wave in mid-2021, infections started to increase late in December. Daily COVID-19 cases stayed below two thousand; however, infections increased after omicron was identified, and new daily cases now number around 12 thousand (chart 2). The government projects that by February Colombia could face new case levels similar to those of the third wave (between 30 and 40 thousand daily cases). For now, mortality rates remain subdued and, at roughly 50 persons per day, are at levels registered in the calmest months of the pandemic. Some companies are opting again for remote work arrangements, while schools are expected to fully return to classes by the end of January. Some traditional festivals were cancelled or partially restricted, which would impact business in small cities.

However, as more than 55% of the population is fully vaccinated and the booster doses rollout advances, we don’t expect material restrictions in the forthcoming weeks.

Mexico—Outlook for 2022

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

+52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

Inflation in Mexico gave us a positive surprise at the end of 2021, closing the year at 7.36%, below the consensus expectation of 7.45%. However, it still printed over two times higher than Banxico’s target. Although price pressures will remain over the course of 2022, the rate of inflation looks set to fall due to statistical effects, particularly into the second half of the year. However, there are several price-related issues that will continue to impact the economy. The first is that over the past two years consumer spending patterns have experienced material shifts away from services, towards goods. These changes are likely to reverse (although we don’t know what the post-pandemic consumer basket will look like, as some behaviour shifts may be permanent). In any event, the reality is that the rate of inflation actually borne by consumers over the past two years in Mexico has been higher than INEGI’s CPI basket shows, as services have dampened the CPI inflation, at a time when consumption of services has been over-represented in consumer spending index weightings. In some ways, CPI metrics are underestimating the adverse impact of multiple ongoing price shocks on consumers and their balance sheets.

A second issue is that the multi-speed recovery has been vastly stronger in the sub-sectors where consumers are increasing spending. This implies that part of the price pressures likely come from demand-side shocks. Output in those sectors has recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and demand has done so as well, meaning sectoral level output gaps have closed. In addition, consistent with the Fed’s ditching references to “temporary” price shocks, after 1.5–2 years of above-target inflation, and even worse pressures on PPIs, it may be a good idea to remember that, as John Maynard Keynes wrote, “in the long run, we are all dead”.

The fact remains that core inflation in Mexico is almost twice Banxico’s 3% +/-1 target (it closed 2021 at 5.94%), and some components such as services, which had not seen PPI side pressures, started experiencing them a few months back.

In this complex inflation environment, Banxico is going through a leadership change, while keeping its remaining four Board members in place. How will the leadership change affect policy? We’re not quite sure how new Governor Rodriguez Ceja will lean in her monetary policy views, with her presentation in the Senate being among the few instances in which she has provided a glimpse into her views. There is some speculation that, as she gets up to speed, she could lean on Deputy Governor Esquivel, who in the past has been a mentor to her. If this is true, she could share the view defended by Esquivel (and on January 6 shared by Deputy Finance Minister Yorio) that monetary policy is ineffective against the type of inflation shock facing the Mexican economy. If that is the case, Banxico is set to have one more dovish leaning vote (Esquivel supported a 25 bps hike, as opposed to the delivered 50 bps in the last policy meeting of 2021, and before that defended pauses). Based on the latest minutes, we think the odds of the rest of the Board keeping the tightening pace at 50 bps in the coming meeting (February 10) are close to even, which is not far from the average analyst estimate of 36 bps in the latest Banamex survey, from January 5. Similarly, the TIIE curve is pricing in 75 bps of tightening over the coming two meetings. At the end of last year, we tweaked our terminal rate estimates, and now look for Banxico to end its hiking cycle slightly on the tight side, as opposed to the neutral settings we previously anticipated. A more front-loaded cycle could help keep the terminal rate lower by anchoring expectations.

On a separate topic, it has been announced that Mexico is considering launching a “digital peso” by 2024. One potential implication of this move would be to reduce pressure on Banxico to buy USD directly on the market, which some pockets in the legislative have been pushing for. With a digital MXN, remittances would now more easily flow through this channel, helping reduce political pressure from the surplus of dollars being stuck in the balance sheets of local banks without international counterparties.

In the policy and political arena, the year kicks off with the government announcing that a new package of public-private partnerships on infrastructure will be unveiled soon, as the country struggles to jump-start investment, which has fallen about 3–4 percentage points of GDP from its average in the 2010–2018 period. Finance Minister Rogelio Ramirez de la O has hinted one of his objectives is to restore private sector confidence, to strengthen investment, and thus support what has been very anemic growth over the past three years. This program may be the first test on that front. The 2022 Mexican Government budget is built around a 4.1% growth assumption, which is materially higher than both our own estimate of 2.8% and the 2.7% consensus in the latest Banamex survey. The other topic to monitor in the first quarter of 2022 will be the evolution of Lopez Obrador’s planned referendum on his mandate revocation. The electoral authority has indicted it was not allocated sufficient resources to organize it, thus turning the issue into a friction point between the autonomous electoral institute (the INE) and the government, which should be resolved over the coming weeks.

Peru—2022 Starts Off with a More Stable Political Footing, as the Issues Turn to the Economy and COVID-19

Guillermo Arbe, Head Economist, Peru

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

The new year has begun with a surge in health issues, signs of a mildly slowing economy, and hopes for a quieter year on the political front.

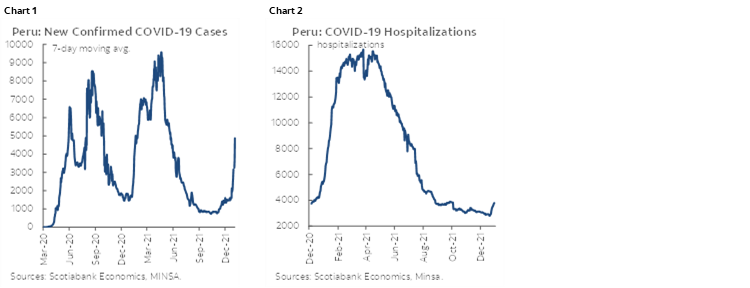

COVID-19 contagion rates are on the rise, albeit off very low levels (chart 1). Cases are still far from the peaks of the two previous waves, and hospitalizations—including ICU—while no longer falling, remain low (chart 2). Having said that, the level of alarm is clearly increasing. Minor mobility restrictions have been put into place so far, including lower capacity levels and a curfew from 11pm to 4am. Given how limited the restrictions are, it would be premature to change our forecast of 2.6% GDP growth for 2022. There is a risk that the restrictions will be increased, but would probably not be greater than the moderate mobility restrictions put into place in February 2020, which had a material, but short-term, impact on growth that was, in the end, absorbed by the following strong rebound in the economy. The greater concern is that if new mobility restrictions are required, they will be introduced in an economy that is slowing, which is a very different environment than a year ago.

The year opens with several political issues but, at the same time, the political noise is lower than before. One could argue that this is simply a reflection of the ebb and flow of political tides. However, there seems to be more to it than that. The political front may be settling down. Most major contentious issues are either settled or have been pushed to the indefinite future. The attempt to impeach President Castillo is over and off the agenda; the possibility of a Constitutional Assembly is no longer being discussed; the more controversial members of the cabinet have been removed and the current cabinet may actually be able to get some work done; and the possibility of an increase in taxes has been pushed into 2023 at earliest. Social conflicts continue to be a risk, but no roads are being blocked at the moment. The Attorney General’s office opened an investigation on President Castillo’s involvement in the questionable tender of biodiesel to the State company Petroperú, but immediately suspended the proceedings until after Castillo’s term ends (Presidents in office cannot be indicted). The next political events on the agenda are the regional and municipal elections to take place on October 2, far enough in the future not to rock the boat, but soon enough to start absorbing the attention of political parties. Given the nature of the government and the degree of polarization in the country, Peru is still prone to political event risk in 2022, and, certainly, poor State management will continue to be an issue but, at the same time, there is a greater chance that day-to-day economic activity will face more a state of political discomfort than of outright turbulence.

GDP growth in 2021 is likely to end up over 13%, compared to our forecast of 12.3%. But, let’s not get too excited, as there have been signs that growth has been slowing down since October. It’s too early to be sure, but the slowdown appears to go beyond the simple ending of the post-COVID-19 rebound. GDP rose 4.6% y/y in October, but the worrisome issue is that it fell by -1.0% in month-on-month terms. This monthly decline was led by two key sectors linked to domestic demand—construction and manufacturing. Early indicators for November signal weak construction growth, suggesting that October figures were not one-off.

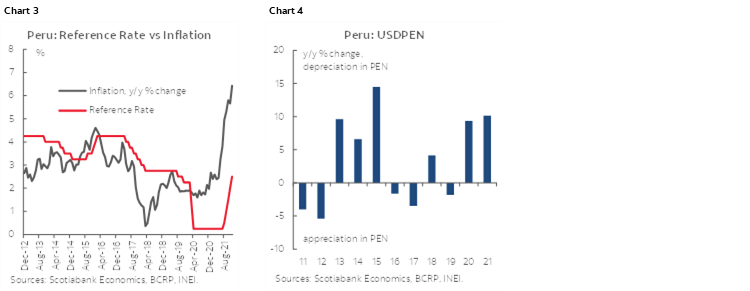

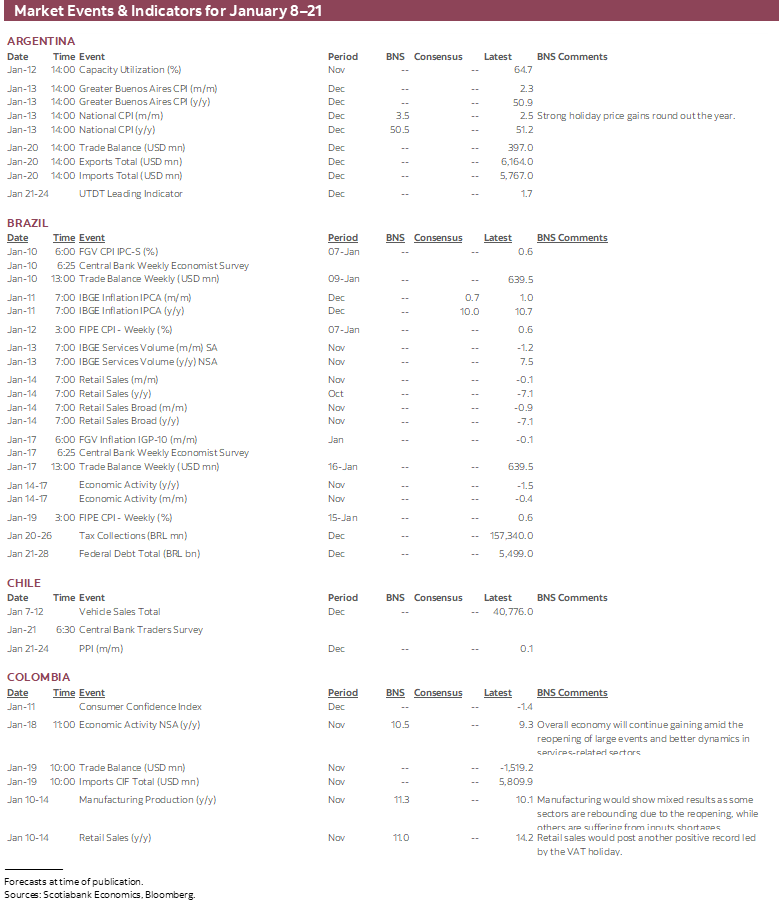

Inflation in 2021 ended at 6.43%, marginally below our forecast of 6.5% (chart 3). Although there are reasons to believe that inflation will moderate, especially early in 2022, it will take quite a bit for it to drop back into the BCRP target range of 1% to 3%. However, the appreciation of the PEN, which has already begun and may continue throughout Q1, will help stabilize prices (chart 4).

Perhaps the best news at the end of the year is the fiscal deficit. The official full-year 2021 figure has not been released yet, but Finance Minister Pedro Francke stated in a newspaper column that it would likely have ended at 2.8% of GDP. If so, this would represent an impressive improvement from 8.9% of GDP at this time last year. Given this, we are tempted to lower our forecast for 2022, currently at 3.5%, which is under revision. Note, however, that in 2021 fiscal revenue included a number of one-offs, mainly from companies paying back taxes under litigation with the tax authority, Sunat, which will not be seen nearly as much in 2022. Thus, although we may lower our 3.5% of GDP forecast, the deficit will not necessarily fall further from the 2.8% of GDP in 2021, as provided by Finance Minister Francke.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.