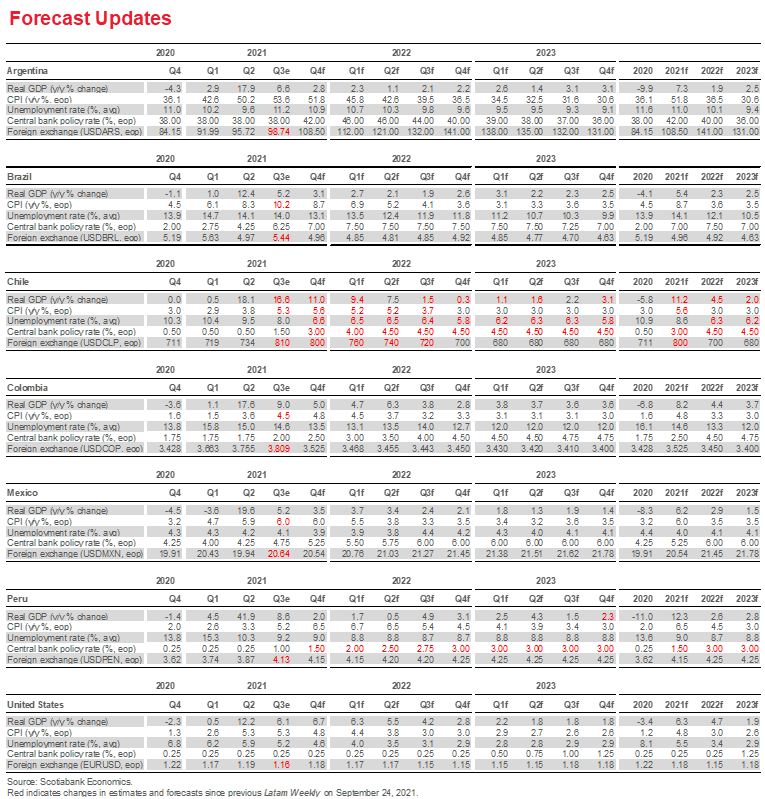

FORECAST UPDATES

- Stronger growth and higher inflation continue to prompt updates to key variables.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- The key question on the minds of international investors, central bankers and other policy makers is whether the current spike in inflation is a temporary phenomenon or could be more persistent.

- The answer to that question is hugely important, as it could trigger an unexpected shift in global financial conditions.

- For Latam countries, the stakes are especially high given their exposure to foreign—US—interest rate shocks. The effects of higher US rates are magnified by domestic vulnerabilities, which can also increase exposure to sudden stops in capital inflows.

- The strengthening of key economic institutions and adoption of sound policy frameworks by Latam countries over the past two decades should limit these effects, but risks remain.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

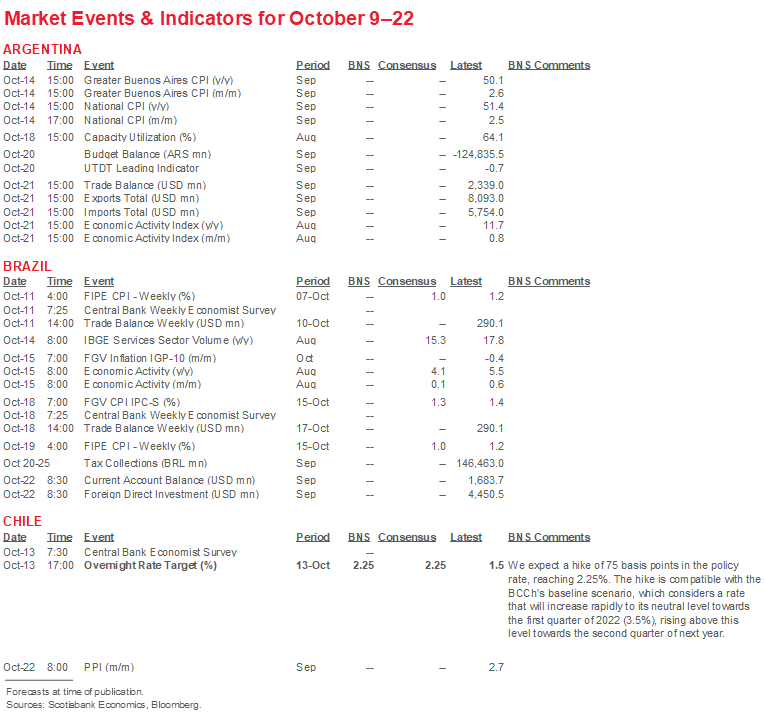

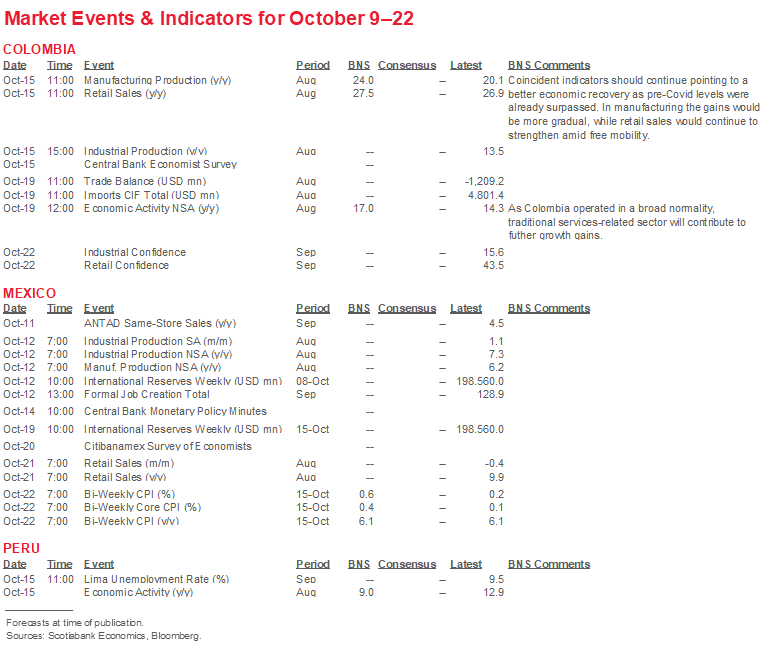

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period October 9–22 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: Temporary or Persistent?

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Latam central banks, like their counterparts around the globe, are grappling with the question of whether current price pressures are temporary or could prove more persistent.

- Getting the right answer is hugely important. Higher inflation could increase their vulnerability to unexpected interest rate shocks.

- The strengthening of key economic institutions and the adoption of sound policy frameworks across much of the region over the past two decades should increase resilience to these shocks.

- But the region’s central banks may not have the optioning of pondering the question if indecision increases vulnerabilities to the eventual rebalancing of global financial conditions.

THE COST OF INDECISION

The key issue on the minds of investors, central bankers, and policy makers in the Latam region and around the globe is whether the current spike in inflation rates represents a temporary phenomenon—one that will dissipate over time—or is likely to prove more persistent. For now, the balance of informed opinion among central bankers and the prevailing private sector consensus is that higher inflation in key advanced economies, especially the US, reflects a combination of base effects (with price pressures in 2020 temporarily suppressed by the pandemic) and transitory shocks to global supply chains. Patience, it is argued, is needed to wait out these effects and will be rewarded with a timely return of inflation to levels consistent with price stability commitments.

This benign perspective may well be proven right over time. But the longer high inflation persists, with only modest decreases as base effects play out, the less credible that view may appear. And the longer that inflation remains above long-run targets, the greater the risk that inflation expectations are ratcheted higher and become embedded in wage increases and anticipatory price increases. In such circumstances, central banks may opt to move early to preempt inflation anchors from becoming unmoored.

In effect, therefore, the current conjuncture could be summed up in a riff on Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “whether inflation is temporary or persistent—that is the question.”

The answer to this question is hugely consequential. Global markets have been fueled by a decade-long period of historically-low interest rates. This low-rate environment, which was initiated in the global financial crisis and extended by extraordinary central bank responses to the pandemic, has pushed asset prices higher and may have contributed to excessive risk-taking that will only be revealed under less favourable financial conditions. And while the risk of an unexpected tightening in the advanced economies seems modest at most, with Scotiabank Economics not calling for a Fed rate increase until Q1-2023 at the earliest, it is not too soon to begin thinking of possible consequences should the Fed move earlier.

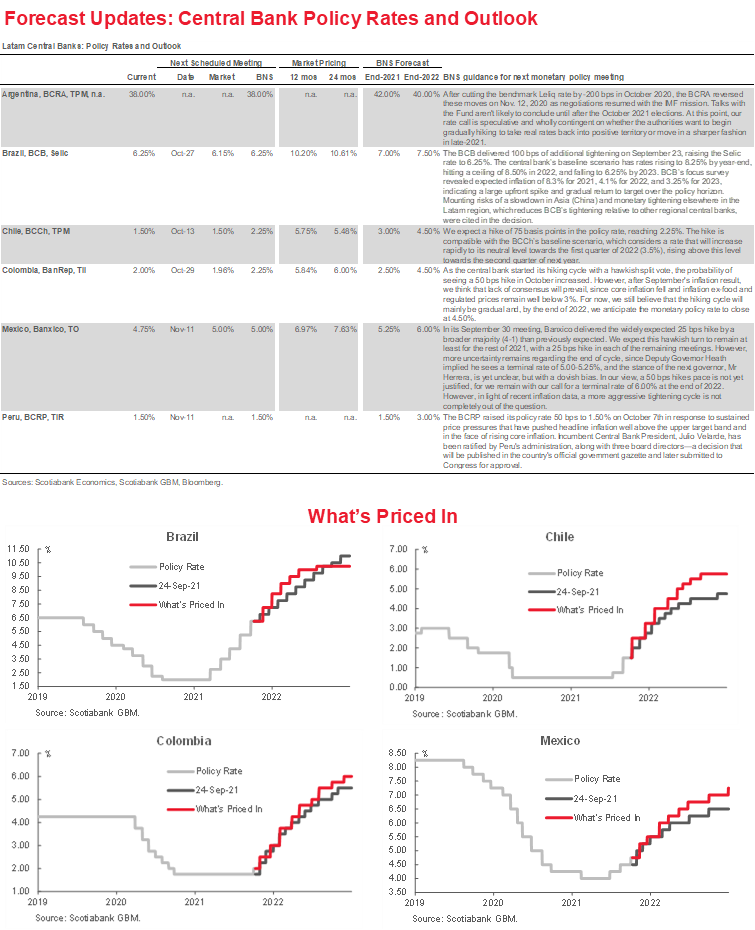

Latam countries are already grappling with the temporary versus persistent question. They have led other central bankers in terms of embarking on tightening cycles. All have raised policy rates, Brazil and Mexico most aggressively, though experiences with respect to recent price pressures vary across the region.

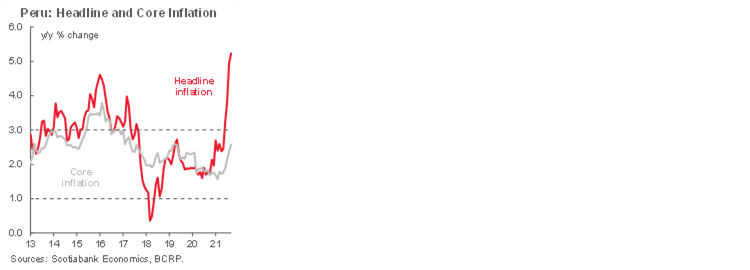

While all Latam countries have seen headline inflation above inflation-targeting upper bounds, individual country experiences and potential risks to inflation anchors differ across the region. In Colombia, for example, core inflation remains well within BanRep’s target bands. (Our team in Bogota provide a detailed analysis of inflation developments here.) In contrast, both headline and core inflation have been persistently above Banxico’s upper band, which Scotiabank’s economists in Mexico City attribute to the “nuanced evolution” of the economy over the past year or so. In Chile, headline inflation is well above BCCh’s upper band, while core remains within the target range, though it is trending higher. As noted below, Scotiabank’s economists in Santiago see nascent signs of persistence in recent price pressures. And as our team in Peru note below, the latest reading on CPI inflation shows that headline inflation exceeds the upper target range by a wide margin, while core inflation remains within the target band—yet it too is trending threateningly higher.

Getting the right answer to the temporary versus persistent question is critical in terms of the timing and pace of tightening needed to quell domestic inflation and preserve price stability commitments. But, as alluded to above, there is an international dimension as well: The Fed plays an outsized role in determining the global financial conditions that impinge on other countries and the Latam region in particular.

Two elements of this international dimension are of especial interest in the Latam context. The first is the impact of Fed tightening on growth in other countries. A key consideration here is the underlying trigger for the Fed’s policy tightening—whether it reflects strong US growth and the risk of overheating, on the one hand, or concerns that inflation expectations could become unmoored leading to slippage of the nominal anchor, on the other hand. In the first case, the spillover effects of higher US interest rates are offset by higher US growth that pulls in the exports of other countries. That positive effect is absent in the case of Fed tightening triggered by rising inflation expectations.

A comprehensive analysis of the spillover effects of Fed policy shifts by two Fed economists* focuses on three types of linkages—exchange rates, direct trade ties, and various vulnerabilities that could impinge on growth through different financial channels. Their results are consistent with a wide body of research on the insulating properties of flexible exchange rates, which facilitate monetary policies in pursuit of domestic stabilization objectives. This is good news for Latam countries that have adopted inflation-targeting monetary policy frameworks and flexible exchange rates.

Interestingly, however, they find that trade intensity with the US matters much less for emerging markets than is the case with respect to advanced economies. Mexico provides an important caveat to this general result, however, given the high degree of integration it shares with its North American trading partners. Not surprisingly, higher US interest rates that produce a slowing of US growth have a larger negative effect on Mexican output, though less so than might be expected given the extensive trade ties between the two countries. At the same time, while a positive demand shock in the US that triggers Fed tightening has positive spillover effects on emerging markets, these are quickly offset by the negative spillovers of higher US interest rates, and GDP falls below baseline after about one year.

These results may be explained by the fact that the financial channels through which shifts in Fed policy are transmitted are likely far more significant for emerging markets in general and Latam countries specifically. In this respect, the Fed study cited above shows that in countries more vulnerable to financial fragilities GDP falls by much more in response to a US monetary policy tightening as compared to less vulnerable countries. Such effects could arise, for example, as a result of a deterioration in balance sheets that disrupt the orderly flow of credit in an economy.

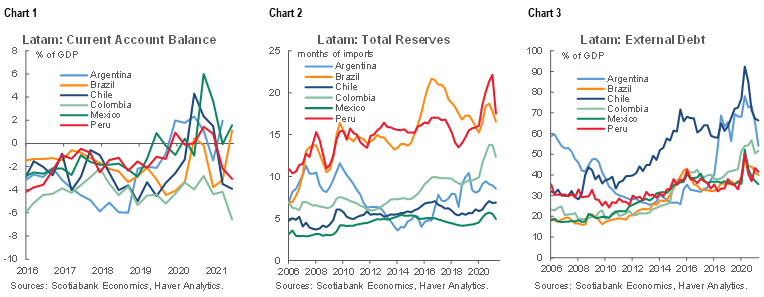

What makes a country more or less vulnerable to these financial channels? Four factors stand out: the current account (chart 1), the level of foreign exchange reserves (chart 2), inflation, and external debt (chart 3). The Fed study finds that all four—inflation especially so—enhance the response of GDP to a US shock in emerging market economies. In this respect, given the steep increase in inflation across the region, Latam central banks may have less scope for exercising patience in assessing the temporary or persistent question if doing so increases vulnerabilities and leads to larger output losses when the Fed and other advanced economy central banks eventually raise rates.

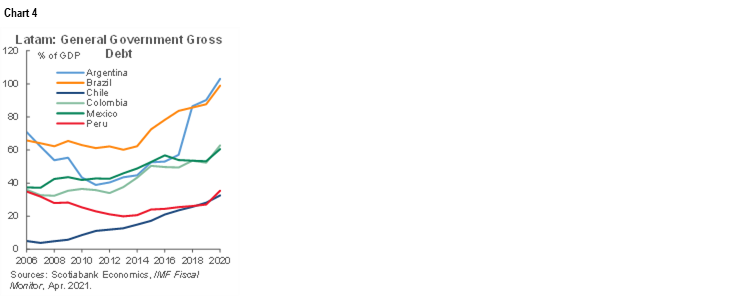

In addition to these four factors, the level of public debt as a share of GDP (chart 4) is likewise an important source of vulnerability. This is because higher public sector deficits (dis-savings) have a direct impact on current account balances through the savings-investment identity, as pointed out below in the Colombia country update. Moreover, whereas private investment is more likely to be financed through foreign direct investment (FDI), which is forward looking and less volatile than portfolio inflows, government expenditures are more likely to be financed by an increase in debt. In this respect, countries with a larger share of FDI inflows are less likely to experience post-surge reversals that end in economic crises. An increase in foreign participation in domestic debt markets, meanwhile, can increase exposure to shifts in investor risk appetite and the risk of “sudden stops” in capital inflows.

The possibility of these abrupt drops in capital inflows is the second international dimension to the temporary versus persistent question. Unexpected interest rate hikes by the Fed are likely to animate a rebalancing of international portfolios with pronounced and immediate effects on capital flows. At the same time, the domestic vulnerabilities discussed above can interact with global factors and increase the likelihood of a sudden stop. Large fiscal and current account deficits, for example, and a high level of liability dollarization increase vulnerability, while ample reserve buffers reduce exposure to sudden stops. Sudden stops are thus more likely to be prevented when there is low dollarization, low inflation, flexible exchange rates, and strong institutions that provide continuity of policy frameworks.

For Latam central banks pondering the temporary or persistent question, this is an encouraging message. After all, important progress has been made across the region in terms of strengthening key economic institutions and implementing sound policy frameworks. But the region’s central banks do not have the option of pondering the question, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet did, if indecision increases vulnerabilities to the eventual rebalancing of global financial conditions.

* Matteo Iacoviello and Gaston Navarro (2018). Foreign Effects of Higher US Interest Rates. International Finance Discussion Papers 1227.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Hectic Political Scenario Ahead of Presidential Election

Jorge Selaive, Chief Economist, Chile

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

56.2.2939.1495 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has slightly increased in recent days, although it remains at its lowest level since the beginning of the pandemic. The positivity rate is likewise at its lowest level, at around 1%, and COVID-19-related deaths continue to decrease. The vaccination campaign has reached 89% of the target population, while the occupancy of ICU beds decline across all age groups. Meanwhile, the rollout of booster doses is making good progress. Thanks to these developments, mobility has increased, returning to pre-pandemic levels in activities related to the workplace. As of October 4, no commune is in lockdown, while more than 95% of the population has reached the highest degree of mobility in the “Paso a Paso” Plan. From October 1, the curfew and the quarantine phase no longer apply anywhere in the country.

On Thursday, September 23, the government presented the 2022 Fiscal Budget bill to Congress. The budget includes expenditures of USD 82 bn, an increase of 3.7% y/y in real terms over 2021 levels net of pandemic-related extraordinary expenditures. Compared with 2021’s extraordinary expenses related to COVID-19, this level of spending represents a decrease of 22.5%. Regarding the macroeconomic outlook, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) increased its GDP growth forecast for 2021 from 7.5% to 9.5% and reduced its forecast for 2022 from 2.9% to 2.5%.

According to the Public Finance Report, the Budget Bill also authorized a maximum for bond issuances of USD 21 bn in 2022, of which USD 20 bn is expected to be issued. All in all, the public debt will increase from 34.9% of GDP in 2021 to 37.5% in 2022.

In the political arena, on Tuesday September 28, the Lower House passed the bill for the fourth 10% pension fund withdrawal. The bill, which is not supported by the administration, will now go to the Senate where it is likely to face greater opposition. At this stage, its outlook is uncertain. According to the MoF, if approved, the measure would inject as much as USD 20 bn into the economy, putting pressure on inflation by stimulating consumption and eventually overheating the economy.

The National Prosecutor, Jorge Abbott, decided to initiate a criminal investigation ex officio for the alleged crimes of bribery and tax evasion in the sale of Minera Dominga, which would involve President Sebastián Piñera. The decision was based on the recommendations of the report issued by the Anticorruption Unit of the National Prosecutor's Office (UNAC), which analyzed information revealed by the international journalistic investigation Pandora Papers on the purchase agreement of Minera Dominga, carried out in a tax haven, at the end of 2010. This investigation is expected to be expedited given its public relevance.

The Chilean peso experienced a significant depreciation with respect to other currencies when news of this investigation became known. We believe it unlikely that this will result in charges against the president, but as long as the investigation lasts, we expect that Chilean financial assets would maintain a relative penalty compared to other peers.

Meanwhile, on Thursday September 30, the INE published the unemployment rate for the quarter that ended in August, which fell from 8.9% to 8.5%. Compared to the last quarter, the decrease in the unemployment rate was explained by a higher increase in the level of employment (+1.3%) compared to the workforce (+0.9%). With these figures, the employment gap with respect to the pre-pandemic levels decreased to 805,000, of which 415,000 corresponds to formal employment yet to be recovered, while 390,000 corresponds to informal employment.

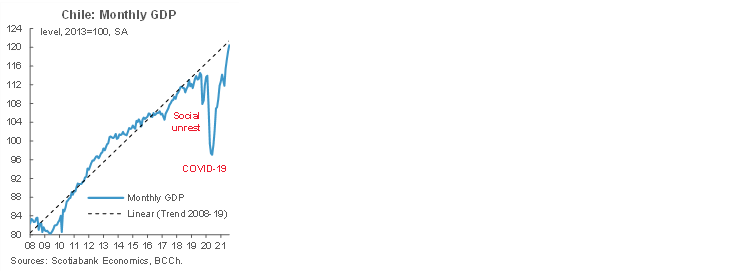

Moreover, on Friday October 1, the central bank released the Imacec indicator for economic activity in August, which expanded 19.1% y/y, below market expectations but close to our forecast of 18.5% y/y. According to the BCCh, the main contributions to the annual economic growth came from services and commerce, but construction and manufacturing sectors also contributed. In seasonally adjusted figures, the Imacec expanded 1.1% m/m, reaching levels similar to the trend observed before the social unrest and pandemic (first chart). For September’s Imacec release, our preliminary assessment calls for an expansion between 12% and 15% y/y.

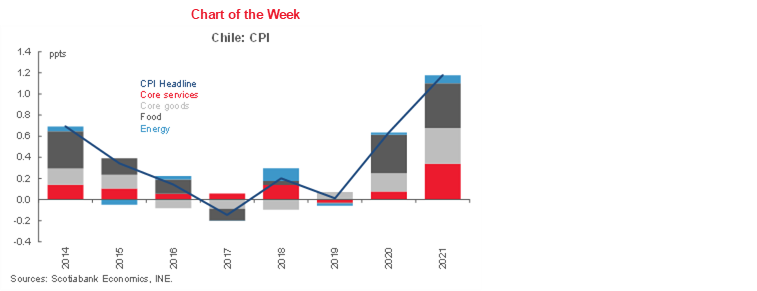

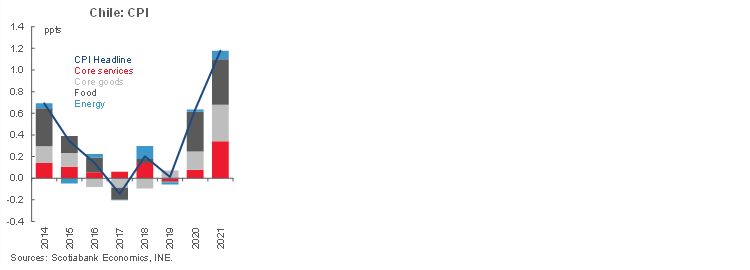

September CPI increased 1.2% m/m (second chart) (5.3% y/y), above both market and our expectations. By component, food prices increased 2.1% m/m, with an incidence of 0.4 percentage points (ppts), while the transportation component increased 2.7% m/m, with an incidence of 0.36 ppts. September's inflation is typically high, but the 2021 record was the second highest in 20 years.

The September outcome suggests a greater degrees of inflationary persistence. We consider that the increases seen at a general level within the basket, mainly in goods, could be explained by the demand shock reflecting the strong dynamism of consumption and the lower capacity of companies to compress margins, resulting from the depreciation of the Chilean peso (CLP). With this, we raised our inflation forecast for December 2021 from 5.0% to 5.6% y/y.

The September CPI record will have important implications for monetary policy. We estimate that at the October 12 and 13 meeting the central bank will discuss two options: (i) increase the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) by 75 basis points (bps), up to 2.25%, until reaching the neutral MPR (3.5%) earlier than was previously foreseen; (ii) increase the MPR by 100 bps, reaching a neutral MPR at the beginning of 2022. We project that due to the deterioration in the international scenario, the central bank will choose to bring the MPR up to 2.25% in October. This hike would be compatible with the BCCh’s baseline scenario, which anticipates a rapid increase in the policy rate to its neutral level towards the first quarter of 2022 (3.5%), rising above this level towards the second quarter of next year.

In the fortnight ahead, the main event will be the next meeting of the Monetary Policy Meeting on October 13, in which we expect a hike of 75 basis points in the policy rate, reaching 2.25%. On the political side, voting in the Senate for a fourth pension funds withdrawal is scheduled for October 27.

Colombia—Twin Deficits: Temporary and Sustainable?

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

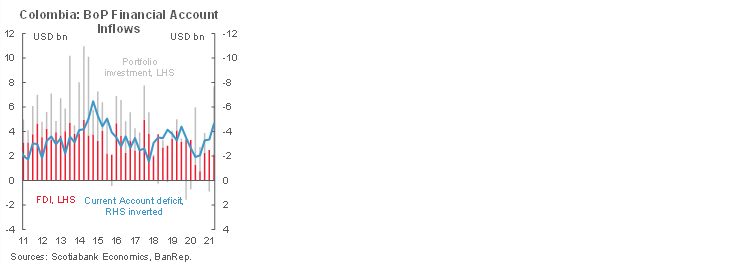

Colombia’s recent history has been characterized by higher current account deficits than the rest of the region, especially in years when domestic demand is on a recovery path or the economy is booming. In fact, on average, current account deficits in Colombia have been 4% of GDP for the last ten years, well above the levels in Brazil and the other Pacific Alliance countries (PAC) as a percentage of GDP: Brazil (2.7%); Chile (2.3%); Mexico (1.6%); and Peru (2.6%). Although it has always been a concern, the fact that the current account deficit has mainly arisen from the private sector, and especially higher imports of raw materials and capital goods, has meant that financing has been readily available. At the same time, a large share of financing coming from foreign direct investment (FDI), which is less volatile than portfolio inflows, has provided some sustainability to the external accounts. In other words, viewed from the perspective of the investment-savings approach to external balances, Colombia’s current account deficit has largely resulted from higher private investment that draws in foreign savings from abroad, which historically has brought its own and long-run financing via FDI.

In the ten years up to 2020, roughly three-quarters of the 4% of GDP average current account deficit has been financed by FDI (first chart). Moreover, in recent years foreign investors have diversified their allocation and in 2019 only 20% of FDI went to the oil and mining sector, while ten years ago this proportion was above 30% on average. Therefore, before the pandemic, higher external imbalances were linked to higher private investment that generated higher domestic demand growth and expanded debt-servicing capacity.

However, over the last two years (2020 and 2021) the source of the external imbalance has changed. The main source hasn’t been from the private sector but higher public deficits that have consumed more external resources and represent a good part of the current account deficit. Although there is no official data that break down external imbalance between private and public sectors, according to official data from the Ministry of Finance’s (MoF) 2021 medium-term fiscal framework, government expenditures in 2020 and 2021 absorbed more than increases in private sector savings. In fact, while private sector savings increased by about 3 ppts of GDP, government expenditure increased by more than 4.5 ppts of GDP. The savings gap was filled mainly by foreign savings, which translates into a higher current account deficit. In the same vein, recent current account deficits had to be financed with higher external public debt and portfolio investment.

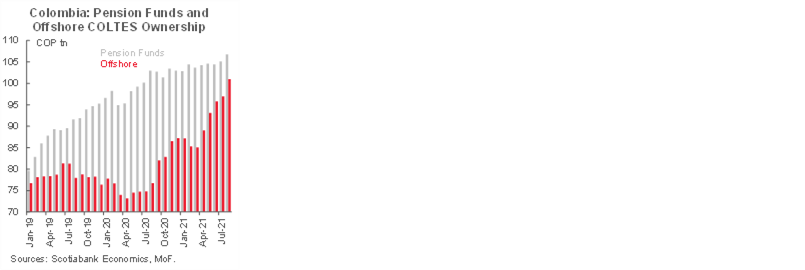

At the beginning of the pandemic, the main source of financing came from a reduction of public savings abroad (public fund for oil prices stabilization). Subsequently, however, external public debt issues, which increased over the last two years from USD 73 bn to USD 92 bn, were the main source of financing of Colombia’s public deficit. Foreign purchases of domestic public debt have also increased significantly; in fact, offshore investors now account for 26% of the total domestic debt, surpassing COP 100 tn in COLTES holdings (second chart), compared to 24% at the beginning of 2020. Foreign investors have been, at the margin, the main borrowers of the government, helping to finance the recent increase in the current account deficit.

The question is whether the external imbalance is as sustainable as in the past, when private investment increased the current account deficit but at the same time created its own financing through FDI. The answer in our opinion is a big NO. Private imbalances that boost potential output and, in theory, produce higher productivity and exports in the future would bring down the current account deficit. In contrast, external imbalances fueled by the public sector increase perceived country risk and can trigger risk-off response if this source of imbalance becomes permanent. The reason for this response is that the imbalances fueled by public sector deficits financed by debt do not necessarily raise potential output. In fact, in many cases, higher public deficits are associated with an unsustainable debt path, higher interest rates or the possibility of a sudden stop to capital inflows. Therefore, if higher external deficits from public sector imbalances continue to create higher FX exposure, external vulnerability and potential risks to the Colombian economy could increase even as economic activity picks up.

Fortunately, recent data, such as BanRep’s weekly external indicators and indications of Capex recovery in the oil and mining sectors, allow us to be optimistic about Q4-2021 and next year’s current account deficit financing. We think a recovery of FDI is on its way and we will go back to the Colombian tradition of a current account deficit higher than peers, but also higher FDI.

Mexico—Power Sector Proposal Presents Controversial Reversal of the Sector’s Opening to Private Investment

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

On October 1, the government presented a bill that seeks to reverse important components of energy sector reforms undertaken in the previous administration. The bill is primarily focused on the power sector, but also includes amendments that affect the broader energy sector. The proposal is highly controversial, as it contains some elements of nationalization of private investment in the power sector, as well as in lithium reserves. Key elements of the bill include:

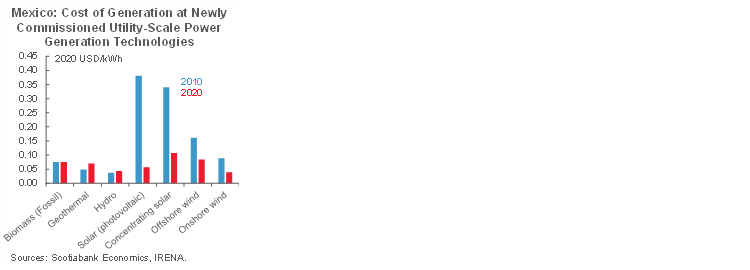

- Capping private players’ access to the power sector at 46% by setting a minimum public sector share of 54%. This measure could affect the country’s power cost structure, as Mexican public sector power generation costs are currently more than twice those of the private sector. Moreover, because the vast majority of renewable energy generation in Mexico is private, the measure could reverse the decline of renewable energy cost relative to fossil fuels (see chart).

- The bill eliminates autonomous commissions such as the CRE (Energy Regulatory Commission) and the CNH (the National Hydrocarbons Commission) and establishes CFE—the public sector power utilityؙ—as the sole regulator of the sector, making it operator, regulator, distributor, and referee of the system. This measure affects the broader energy sector, and tilts the table against private investors, and in favour of CFE, likely further reducing incentives for private investment.

- The bill de facto eliminates the wholesale electricity market system, and also eliminates the generation permits granted to private players under the previous administration. When a similar proposal was introduced earlier some observers argued that it violated international treaties, risking litigation. FDI into the sector since 2014 (when the power market was reformed) coming from the EU, US and Canada has exceeded USD 11 bn, suggesting potential backlash coming from major international partners is material.

- Clean Energy Certificates (CELs), which had served as the biggest incentive for private investment in the sector, would be eliminated. With the elimination of the CELs, the goal of 35% of the country’s power being generated from renewable sources by 2024 seems unlikely to be achieved given limited public sector resources.

- The CENACE, the autonomous power sector operator, would be eliminated, and its functions incorporated into the CFE. This would mean the CFE becomes the entity that buys power generated from the private sector, and at the same time sets the purchase price.

- The bill also establishes that mining and developing the country’s lithium resources would be an exclusive activity for the state, and bars concessions to the private sector. There are significant lithium resources in the country, with the USGS estimating around 1.7 mn tons are available, representing about 2.5% of global resources. Part of these resources have been acquired by foreign and private players, suggesting nationalization is forthcoming.

Will the bill pass? Being a Constitutional reform, the bill needs a 2/3 majority support in both the Senate and the Lower House. In addition, the reform also needs to be ratified by one more than half of State legislatures. The government’s legislative coalition falls short of the necessary votes in both the upper and lower houses, which means it would need support from the opposition.

Peru—Markets React Positively to Political Changes; BCRP Continues Monetary Adjustment

Guillermo Arbe, Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Mario Guerrero, Deputy Head of Economic Research

51.1.211.6000 Ext. 16557 (Peru)

mario.guerrero@scotiabank.com.pe

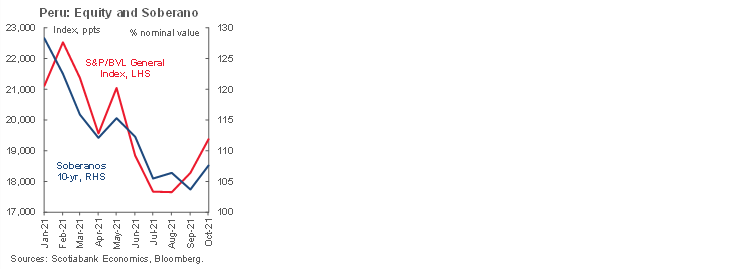

The initial market reaction to the October 6 cabinet shuffle was favourable, marked by a material appreciation across all asset classes (first chart). President Castillo chose to reformulate his cabinet after two months in office characterized by growing political uncertainty. The cabinet changes seemingly address a key leadership issue, somewhat distancing President Castillo from the Peru Libre party. The new cabinet represents an administration that should facilitate governability and foster a better relationship with Congress, with ministers aligned with the moderate left replacing individuals with more radical profiles. In terms of economic policy, President Castillo reaffirmed his commitment to current policy frameworks, retaining the Minister of Finance, Pedro Francke, and in a message to the nation reiterated his commitment to promote private investment.

Difficult political issues remain, however. For instance, new tensions could emerge as some political factions question the government’s strict adherence to the law in seeking congressional approval for the new cabinet. At the same time, the governing party, Peru Libre, continues to collect signatures in favour of a referendum on a Constitutional Assembly. And social conflicts with mining companies, which have been a recurrent issue in Peru, will be the first challenge for the new cabinet to tackle.

COVID-19 cases continue to decline in Peru, in a context in which the Minister of Health, Hernando Ceballos, was reappointed in the new cabinet. According to the authorities, 61% of the current cases correspond to the Delta variant. The government announced an agreement with Moderna for 20 million doses to be delivered in Q1-2022 even though the company has not yet achieved approval of its vaccine by local health authorities.

Meanwhile, the economy is on the path to recovery. Recent figures continue to point to healthy growth and an improvement in the external macroeconomic and fiscal accounts. That said, concerns remain with respect to inflation, exchange rate volatility, and the outlook for private investment.

Leading indicators for August point to a strong performance both in the primary sectors, with recovery of mining production (+ 5.1% y/y), as well as those linked to domestic demand, marked by an increase in domestic cement consumption (+ 15.4% y/y in August) and electricity output (+ 6.7% y/y in September). Moreover, according to figures from the Ministry of Finance, the level of public investment underway is also up (+ 51.0% y/y in August and 16.6% y/y in September). Strong tax collections (+ 50% y/y in September) also reflect the robust pace of activity. These results are in line with our forecast of GDP growth of 12.3% for the full year. The BCRP has indicated that owing to this impressive performance, the economy could return to its pre-pandemic level in Q4-2021. Overall, there is little evidence that political turbulence has had a major impact on economic growth, though a slowdown in lending, which increased 2.5% y/y in August, may reflect lower economic dynamics in the future.

That can’t be said with respect to the currency, as the PEN has been one variable that has reflected the political uncertainty, reaching a record of USDPEN 4.14 during the past week. However, President Castillo’s cabinet restructuring has led to a change in sentiment illustrated by an initial appreciation to 4.06 (moving to around USDPEN 4.09). On the one hand, demand for the Peruvian currency has been driven by the risk appetite of offshore investors while, on the other hand, local corporate and retail agents see an opportunity to buy cheap dollars.

Inflation is the main concern. At 5.2% y/y in September, inflation has already surpassed the updated BCRP forecast of 4.9% for 2021 and is well above its target range (between 1% and 3%) (second chart). Recent announcements of increases in electricity, water, gas and local fuels prices suggest that price dynamics in October could keep inflation on an upward trajectory, in line with our forecast of 6.5% y/y by the year-end. Core inflation has not yet exceeded the target ceiling but is steadily creeping upwards (+ 2.6% y/y in September), reflecting the amplification of higher costs.

Rising production costs have become more widespread, as higher prices for raw materials and energy are compounded by higher global shipping costs. Wholesale inflation, linked to production costs, continues to rise (13% y/y in September) and is at its highest rate in 27 years. These sources of price pressure have not been fully transmitted locally and are likely to persist for the remainder of this year and next.

The rise in inflation and inflation expectations have been pressuring the BCRP to raise its reference interest rate. The central bank has been explicit in stating that it will continue with its policy of gradually raising the reference interest rate. Not doing so, the BCRP argues, could lead to higher inflation expectations and a possible weakening of the price stability commitment. In practice, the BCRP has been basing its policy decisions on the data as it becomes available, raising the benchmark rate, not so much in anticipation of an increase in inflation in the future, but in reaction to recent inflation rates. This leads us to raise our reference interest rate forecast for this year from 1.25% to 1.50% and for 2022 from 2.50% to 3.00%. Despite this adjustment, monetary policy would not lose its expansionary orientation, since interest rates would remain in negative territory in real terms.

Looking ahead, markets will be closely watching developments with respect to the BCRP. The government has confirmed the tenure of Julio Velarde on the Board of the BCRP, with other individuals under consideration for board membership. In this regard, the Economic Commission approved the definition of the criteria for the election of the remaining directors, based on knowledge, a minimum experience of 10 years, and without legal impediments or conflicts of interest.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.