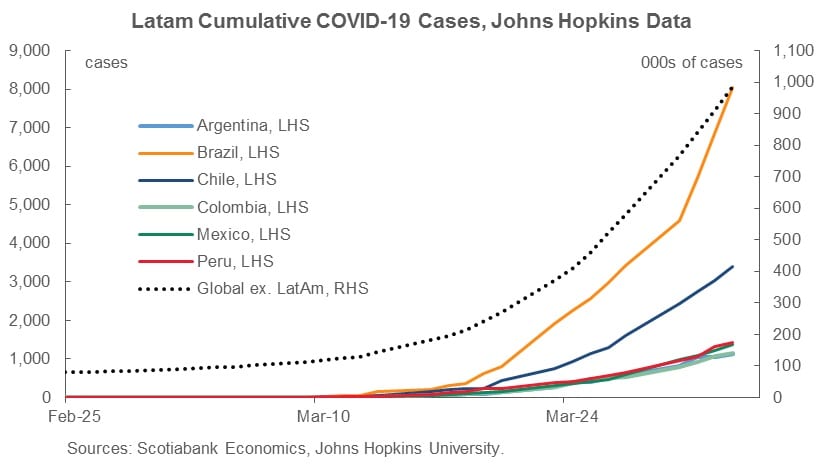

The COVID-19 outbreak continues to spread through Latin America, but the identified number of cases remains lower than in some other countries.

Like the rest of the world, the region is facing a sudden stop in economic activity due to quarantine and shutdown measures to slow the novel coronavirus’ spread, but some countries have stronger footings to weather the crisis, says Brett House, Scotiabank’s deputy chief economist.

Emerging markets are seeing a net outflow of capital larger than what was seen after the 2008 financial crisis, he adds.

Scotiabank Economics recently launched its new Latam Weekly report, a synopsis and synthesis of the fast-moving events impacting the six major economies in the region.

House spoke to Perspectives about what the pandemic means for Latin America, and the challenges of trying to forecast what’s ahead during these extraordinary circumstances.

Q: What's the most pressing issue facing Latin America right now?

A: Like everyplace else, it really is three issues connected to the COVID-19 pandemic. The first one is the advance of new incidences of the disease. The number of identified cases in Latin America is still relatively small, but we know that the number of identified cases is not necessarily an indicator of actual cases on the ground. Testing is ramping up, and we expect to start seeing some big increases in numbers simply because existing cases are being found. The region’s current low numbers mirror the early stages of the exponential growth we've seen elsewhere. The key issue is, will local policymakers, public health agencies, and national security authorities be able to forestall the exponential explosion we've seen elsewhere? Or, if new incidences take off quickly, will they be able to flatten the curve with the various quarantine and physical distancing measures they've put into place?

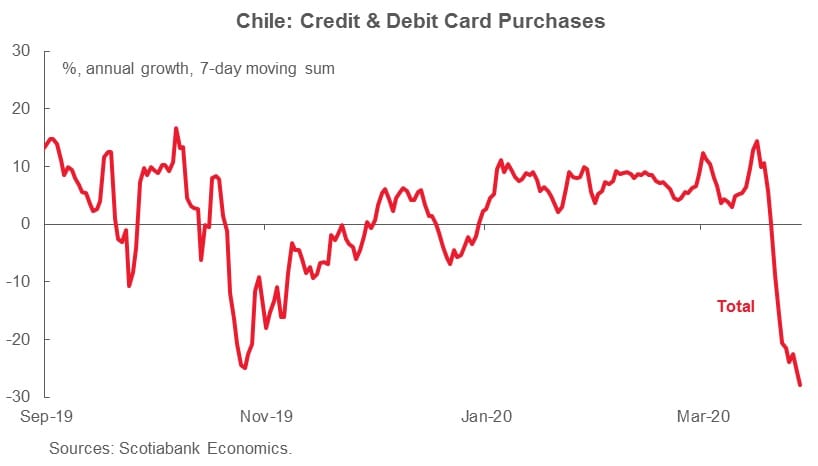

The second big issue in Latin America, like every place else, concerns the economic impact of these quarantine and lockdown measures immediately and over the medium term. The third issue is how quickly and to what extent will the monetary and fiscal policy measures that are being put into place to sustain households and businesses offset the economic damage, dampen the downturn and, we hope, ensure that these economies will be able to restart in a substantial way when these physical restrictions can be relaxed.

Q: What unique challenges does the region face in terms of this pandemic?

A: In recent weeks, emerging markets as a whole have seen a big net outflow of capital which goes far beyond what we saw after the 2008 financial crisis. This is going to create, because of the scale and speed at which this is happening, the potential for particular pressures in all emerging markets. Latin America isn’t immune to these outflows, though we’re only just beginning to get data on a country-by-country basis. Our report talks about how the region is confronting a “sudden stop,” which refers to the slowdown in economic activity owing to COVID-19 control measures, as well as the sudden cut in global demand for exports from Latin America and in capital flows into the region and other emerging markets.

Q: Any particular markets, or sectors, potentially harder hit than others?

A: As in most economies, hospitality, tourism, and any sector that relies on in-person interaction is seeing an immediate impact. Additionally, at a macro level, Colombia and Mexico are major oil producers so they, like Canada, are being hit by a double whammy of a precipitous drop in economic activity as a result of the COVID-19 lockdowns and a damaging global oil price war. If you look at Chile, copper accounts for about a quarter of its exports, so the big drop in global demand will have serious knock-on effects for its economy. Brazil is a larger and more diversified economy, but Argentina comes into the pandemic in an already-weakened state: it’s been in recession since 2018, it’s in the midst of a credit event, and it’s heading toward a sovereign debt restructuring.

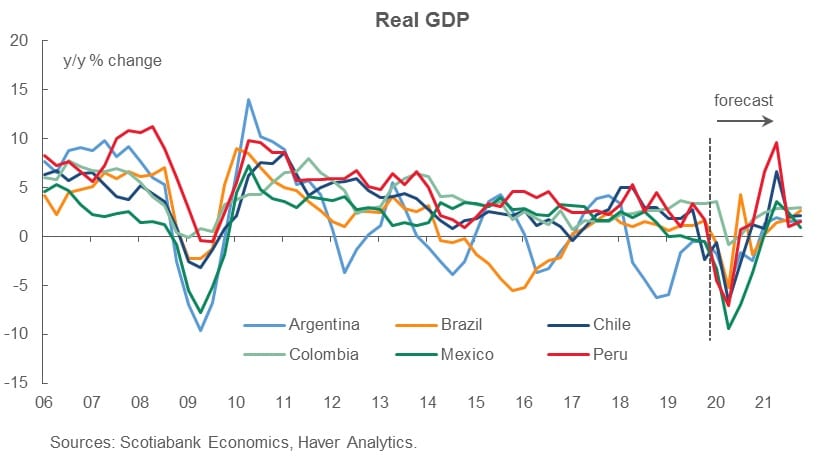

The region’s economies entered this crisis from very different starting points. Those with particularly strong prior fundamentals in place — Peru, Colombia, and Chile — have more flexibility to deal with the crisis in a nimble way.

Q: What is the expectation for economic activity in Latin America at this stage?

A: Our forecasts have been updated three times in the course of March — much more frequently than our normal monthly pace — to account for rapidly changing events. We anticipate that in Latam and in most of the rest of the world, Q2 will see the sharpest quarterly contractions in economic activity that we’ve ever recorded. All of Latam’s major economies are expected to move into some degree of recession this year. This outlook is pretty similar to the consensus of most economic forecasters — all see a big drop-off in economic activity in Q2, but some projected contractions are shallower, some deeper than others. These differences hinge on forecasters’ assumptions about the degree and duration of quarantine measures, and the extent and speed of policy responses to cushion the economic impact.

Compared with consensus views, we are assuming relatively long shutdowns that could last well through the second quarter of 2020 and possibly into the third. Both globally and in Latam, we don’t expect growth to begin turning around until Q3. Growth should strengthen into 2021 and post some strong year-on-year numbers given how weak 2020 is going to be. Substantial slack will remain in most economies into 2021, which implies muted price pressures and little need to move quickly to reverse interest-rate cuts.

Q: Broadly, how have the region’s policymakers responded to the crisis? Do you expect more action to come?

A: Everywhere, policymakers are acting expeditiously to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, and Latam is no exception. Substantial public health and security measures have been put into place, enhanced, and extended. Across Latin America, central banks are loosening monetary policy to support economic activity. Governments are implementing fiscal measures on scales similar to those we're seeing in Europe and North America. For example, Argentina brought forward a fiscal package worth about 3% of GDP and Chile's plan is worth about 4% of its annual income. Peru’s government has gone even further with the recent announcement of a suite of actions worth 12% of its GDP.

Q: How has it been for you and other economists and analysts to comprehend the impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak on the economy? To try to understand and analyze a global event that is incredibly fast-moving and unprecedented?

A: It’s always our job is to assess the information we have and use it to look over the horizon and anticipate what’s coming for the economies we cover. What’s exceptional right now is that the data we have in our hands are changing massively and quickly, and in ways that are difficult to model since we don’t have any prior experience with crises like the current moment. As a result, we approach our work with a lot of humility.

The pandemic and ensuing quarantines together form a classic case of what economists call an “exogenous shock” — a big, unanticipated shift from sources outside the economic system. Some have compared COVID-19 to a meteorite or a massive natural disaster hitting the Earth, but this comparison isn’t quite right. A natural disaster would destroy a lot of our economies’ productive potential. That hasn’t happened — yet. The major parts of our economies still work and are ready to function when the pandemic passes. Medical metaphors make more sense here. Our economies are being put into the equivalent of induced comas — and our policy responses are intended to sustain them on life support so that they’ll be ready to go back to something approaching “normal” when we bring them out of suspended animation.

Q: What can we expect economically once the pandemic is behind us?

A: There's a lot of debate among forecasters over which one of three letters in the alphabet will best describe how the economy develops following the pandemic. There’s some optimism that we’ll see a so-called “V-shaped” recovery — a sharp downturn followed by an equally quick rebound. Given the degree to which our economies are being shut down and the time it is taking to get all of our fiscal support measures in place, this strikes us as increasingly unlikely. The path for many economies is likely to be a bit more “U-shaped” — with the contraction in most countries followed by more gradual recoveries as business activities resume in phases.

The longer it takes to lift quarantines, the more likely we are to see “L-shaped” economic paths, where the recovery from the pandemic is quite gradual and drawn out. The longer it takes to soften shutdown and distancing measures, the greater the risk that we lose some productive capacity on a semi-permanent basis. We know that the longer people remain out of work, the more their skills get compromised. The longer businesses are closed, the greater their risk of bankruptcy. The shape of the recovery has real implications for people’s lives.