The new leadership of Brazil’s National Congress seems supportive of Pres. Bolsonaro’s reform agenda and opposed to impeachment proceedings that could become a distraction for the national government.

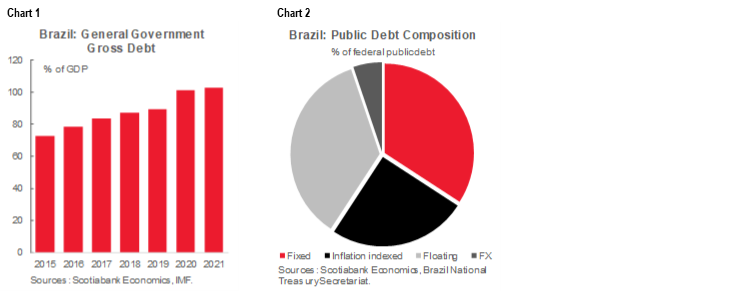

Fiscal risks are set to be among the key issues of 2021. Gross general government debt has topped 100% of GDP and policymakers are likely to be forced to strike a balance between fresh support for the economy and long-term fiscal sustainability.

Fiscal sustainability should also be a key factor in the BCB’s decision-making process as about 28% of federal public debt will need to be rolled over in 2021; additionally, only 34% of the total federal debt stock carries a truly fixed rate. An inflationary spiral necessitating rate hikes could undermine fiscal sustainability; hence, efforts by the BCB to get ahead of inflation would be key to containing fiscal risks.

Brazil’s economy should recover to its 2019 levels of activity early in 2022. At this stage, the authorities ought to focus on moving beyond stimulus-driven consumption to more broadly-based growth. A commitment to fiscal discipline and microeconomic reforms will be essential to restore confidence and boost investment.

Progress on the fiscal front, even if incomplete, alongside a large and front-loaded BCB tightening cycle, could make the BRL among the world’s top-performing emerging-market currencies in 2021.

THE POLITICS OF FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY

The February 1 election of new leadership for both houses of the National Congress was one of the first important events for Brazil in 2021. In the Lower House (i.e., the Chamber of Deputies), the Bolsonaro-backed candidate, Arthur Lira of the centre-right Progressive Party (PP) comfortably bested Baleia Rossi of the Movement for Brazilian Democracy (MDB), which also sits in the centre-right of the country’s political spectrum; Lira garnered 302 of a possible 513 votes for the Presidency of the Chamber. In the Senate, Bolsonaro-supported Rodrigo Pacheco from the Democratic Party (DEM) beat Simon Tebet (MDB) to become President of the Upper House. In Brazil’s Congress, the President of each House has the important power of defining the legislature’s agenda and what will—or won’t—be put to a vote; the role is akin to “Speaker” in other systems. As a result, securing government-friendly leadership in Congress is an important first step for progress on Pres. Bolsonaro’s reform agenda, which includes fiscal adjustment. The new Congressional leadership should also reduce the risk that impeachment bills could become a distraction for the government in 2021.

It remains unclear whether Brazil’s surging second wave of COVID-19 will prompt a new round of public support payments. The two new leaders in Congress have been trying to walk a fine line between being constructive on an additional stimulus bill and at the same time signaling that they would back fiscal consolidation efforts. A majority of legislators seem to back maintenance of the existing spending ceiling, which would be crucial for fiscal credibility. The first key battle in this fight is emerging around the expiry on Wednesday, February 10 (today), of Provisional Measure nª 1000 of 2020, which extended emergency transfers of BRL 300 to families through December 2020. If the economy continues to suffer as the pandemic worsens, we could see Congress’ new leadership rapidly engulfed in a tussle over a new economic support bill. One potential alternative could be a version of the Renda Brasil proposal (i.e., a basic-income program), which Pacheco, as well as Finance Minister Guedes, previously supported.

Given the already shaky state of public finances, if new fiscal support measures are approved they will need to be accompanied by legislation to secure some post-pandemic fiscal adjustment. Ideally, such legislation would include pre-approval of tax proposals that would be gradually implemented over the coming years, as well as pre-set spending cuts or caps. It is important that future fiscal adjustment is approved in 2021 as presidential, legislative, and state gubernatorial elections due in October 2022 will make tax hikes and/or spending cuts difficult to advance next year.

THE CENTRAL BANK HAS A ROLE TO PLAY IN FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY TOO

Politics are not the only relevant piece of Brazil’s fiscal-sustainability puzzle: monetary policy has a role to play as well. Brazil’s gross general government debt has already topped 100% of GDP (chart 1). In addition, as we have highlighted in the past, 28% of Brazil’s public debt will need to be rolled over in 2021, and an additional 15% of the public debt stock will come due in 2022. Moreover, only 34% of Brazil’s total public debt stock carries truly fixed interest rates (chart 2). Of the rest, 25% is indexed to inflation, 36% carries floating rates, and 5% is denominated in foreign currencies. With such a large share of Brazil’s public debt coming due in the near term, and an even larger share indexed to inflation or featuring floating rates, an acceleration in inflation that precipitates rate hikes by the Banco do Brasil (BCB) would put pressure on the national government’s fiscal accounts.

This context makes it easier to understand the quick flip in the BCB’s monetary-policy stance from the introduction of dovish forward guidance in August 2020 to its formal elimination at the Copom’s January 20, 2021 meeting. Even though the Copom unanimously decided to hold the Selic at 2.00%, talk of hikes managed to make its way into the meeting’s discussions: “some members questioned whether it would still be appropriate to maintain an extraordinarily high degree of stimulus.”

We think that concerns about fiscal sustainability sit at the core of the BCB’s newfound hawkishness. As the Copom highlighted at its January 20 meeting, “...an extension of fiscal policy responses to the pandemic that aggravates the fiscal path or a frustration with the continuation of the reform agenda may increase the risk premium. The relative increase in the risks of these events implies an upward asymmetry to the balance of risks, i.e., in the direction of higher-than-expected paths for inflation over the relevant horizon for monetary policy.”

Although the unwind of public support to households could help curb some of the ongoing upward pressures on headline inflation, there is uncertainty about what lies ahead for prices in Brazil on two grounds: first, it’s unclear whether indexation will keep driving inflation forward; and second, we don’t yet know whether we’ll see an additional round of fiscal support measures in the coming weeks. In the event, IPCA inflation came down sequentially from 1.35% m/m (4.52% y/y) in December to 0.25% m/m (4.56% y/y) in January, below the Bloomberg consensus of 0.31% m/m (4.62% y/y). We’ll continue to monitor inflation in February and March for a more definitive view on indexation. On the fiscal front, we see legislative discussions accelerating in the second half of February and extending into March as the new Presidents (i.e., Speakers) of the Chamber of Deputies and Senate flesh out their respective bodies’ calendars.

While we are likely to see binary outcomes ahead—little indexation or a lot, no additional fiscal support or a substantial package—our baseline expectations anticipate a combination in between these poles as a compromise forecast (see our February 8 Latam Weekly). We assume positive, but modest, indexation pressures, and a limited fiscal support package equivalent to 1% of GDP; we also anticipate some partial, but imperfect, progress on setting forward-looking spending caps and tax changes that would deliver additional fiscal revenues amounting to 1 to 2% of GDP.

Under our baseline forecasts, the BCB would start its tightening cycle during Q2-2021 and deliver a front-loaded tightening process. We expect the Selic rate to end 2021 at 4.50% and hit 6.50% by end-2022. With the benchmark nominal policy rate at 6.50%, the BCB would have brought real policy rates close to estimates of the real neutral rate over the coming two years.

ECONOMIC REBOUND AND BRL PROSPECTS

After a strong economic policy response to 2020’s COVID-19 shock, the government must now work to right the ship. The Brazilian economy could be among the first in the region to recover 2019 levels of economic activity (see our Latam Weekly from January 25), owing in part to the aggressive fiscal support the government provided last year. However, fading fiscal measures—even a new round of policy initiatives is expected to be materially smaller than 2020’s package—now need to be followed by a sustainable rebound in economic activity. Over the past decade, Brazil’s potential GDP growth dropped from the 4% y/y or higher observed during the first decade of the millennium to a figure closer to 2% y/y in recent years. Boosting potential growth would require: (1) stronger investment; (2) more effective government, as it currently spends too much with poor results; and (3) microeconomic reforms to raise productivity. To some degree, this discussion of the means by which the potential growth rate could be raised would only bear fruit beyond our two-year forecast horizon. At this point, strong private confidence could be enough to propel the higher growth rates we’ve projected in 2021 and 2022, but it wouldn’t be enough to sustain them.

In 2021, we expect the first quarter’s GDP print to be somewhat weighed down by a combination of the end of 2020’s fiscal support and new restrictions in response to COVID-19’s second wave in Brazil and around the world. However, as the year moves on, we project a robust increase in economic activity to ensue. Although we do not think Brazil will quite recover 2019 GDP levels in 2021, we do expect a full rebound from the crisis by early-2022.

We anticipate that the BCB will undertake an aggressive and front-loaded hiking cycle to limit the terminal rate that would be needed to contain inflation—and thereby cushion the ultimate impact of interest-rate increases on the government’s debt-service costs. The BCB’s moves, combined some progress on the fiscal front, could provide a lift to the BRL. We believe that the real could roll back about two-thirds of the losses it experienced during 2020, making it one of the best-performing emerging-markets currencies in 2021. But if these two positive shocks don’t materialize, the BRL could remain stuck in its current slump.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.