COVID-19 positivity rates are on the rise again across most of Latam, implying that, outside Chile, testing isn’t keeping up with contagion.

Vaccines are beginning to arrive in Latam, but even under a best-case scenario, countries in the region are unlikely to achieve herd immunity through a combination of infections and vaccinations until 2022.

MAKING SENSE OF DATA ON THE SECOND WAVE

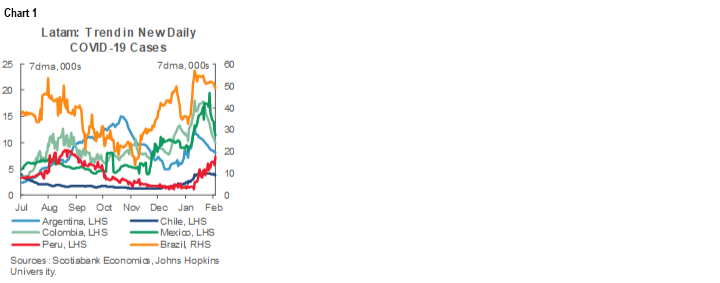

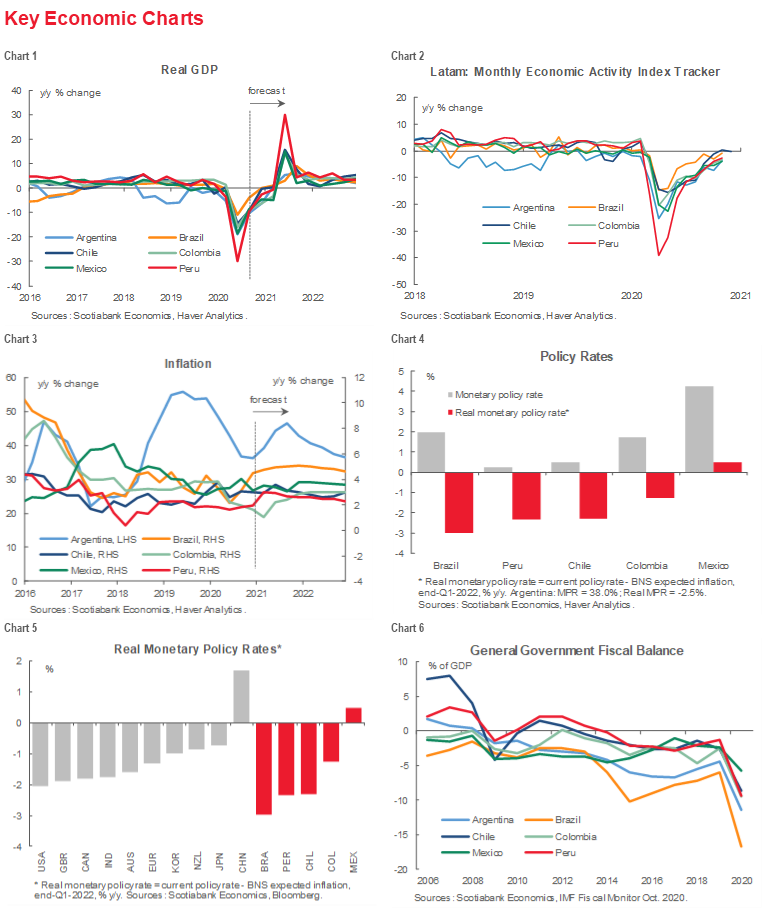

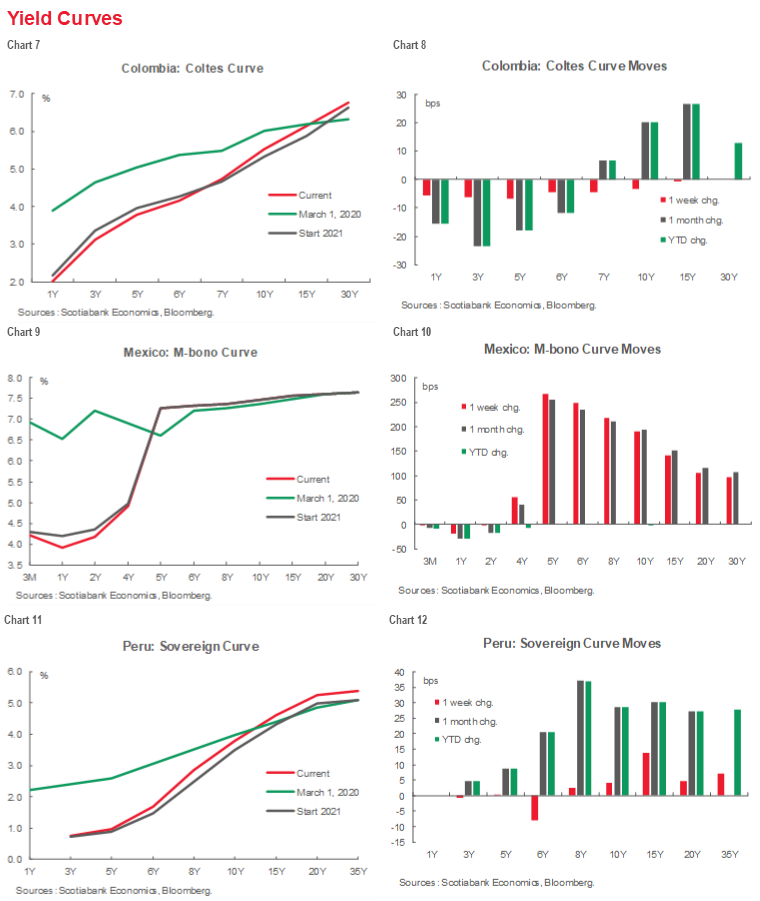

Second-wave COVID-19 new case numbers have risen significantly from a couple weeks ago in Latam’s major economies (chart 1). Following the experience of other regions, new case counts in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru are at or just below their highest levels of the entire pandemic. Argentina’s and Colombia’s new COVID-19 infection numbers, however, have fallen from their peaks in early-January following the re-imposition of a range of restrictions on activity.

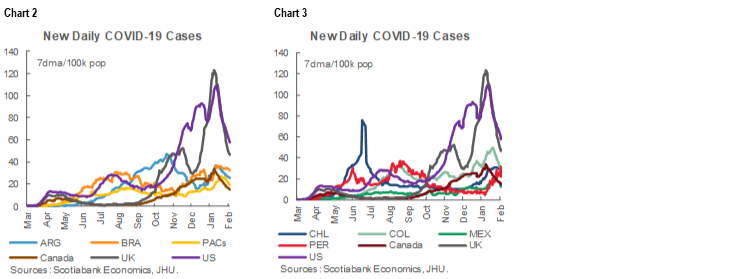

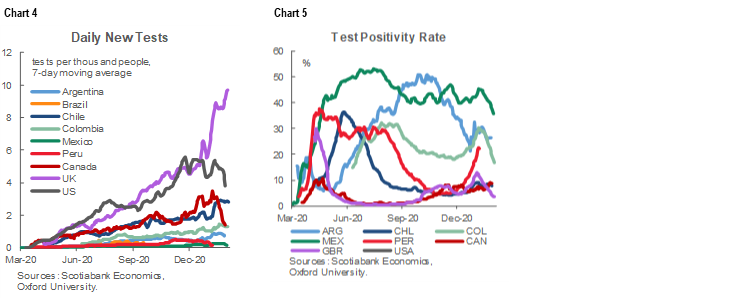

Latam’s per capita official new case numbers remain well below those in the UK and US (charts 2 and 3), but it’s likely that COVID-19 numbers in the region are being underestimated owing to insufficient testing. Chile is the only major Latam country that has ramped up testing rates in response to the COVID-19 second wave (chart 4). At over 37%, the test positivity rate in Mexico is about eight times higher than the US’s 4.7% (chart 5). Positivity rates are also high in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia, which signals second waves that are more significant than the official data are capturing. Data for Brazil, were it easily available, would almost certainly be sending similar signals. Only Chile, with an 8.2% positivity rate, well below its 40% peak in Q2-2020 and now on par with Canada’s (chart 5, again), appears to be testing at the scope and scale necessary to get an accurate picture of the extent and pace of novel coronavirus contagion in Latam.

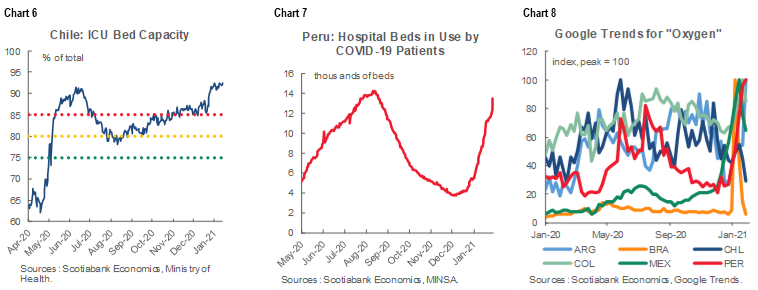

Other data points provide sound indicators of the extent of the recent resurgence in COVID-19 in Latam. Hospitalizations in Chile and Peru are back to the critical levels we last saw at the onset of the pandemic in Q2-2020 (charts 6 and 7, respectively). Google searches for “oxygen” surged during January everywhere in Latam except Chile (chart 8), which is a reliable mark of the increasing number and gravity of COVID-19 cases with health systems nearing their limits.

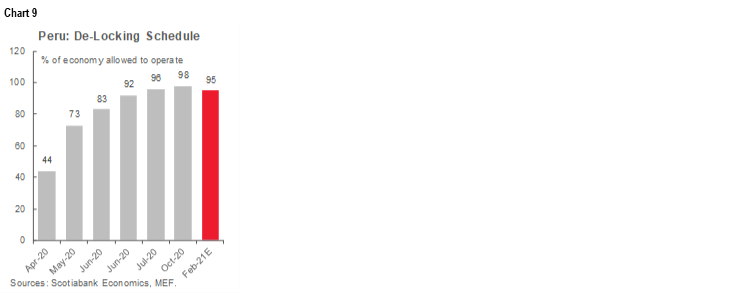

Moves to revisit some of last year’s quarantine measures in Chile don’t appear to have dented growth at end-2020 (see our February 2 Latam Daily), and new lockdowns in Peru are expected to roll back its economic re-opening only from 98% to 95% of total activity (chart 9; see also our February 1 Latam Daily). Following lessons learned during the first wave of COVID-19, new public-health measures appear to be more closely targeted than before; similarly, companies and individuals are better able to respond flexibly and effectively to additional restrictions, thereby paring the economic damage from efforts to control the pandemic.

VACCINATIONS: PRODUCTION, PURCHASES, DELIVERIES, & ROLL-OUTS

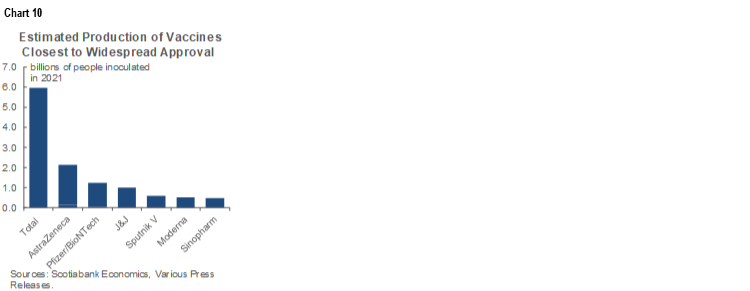

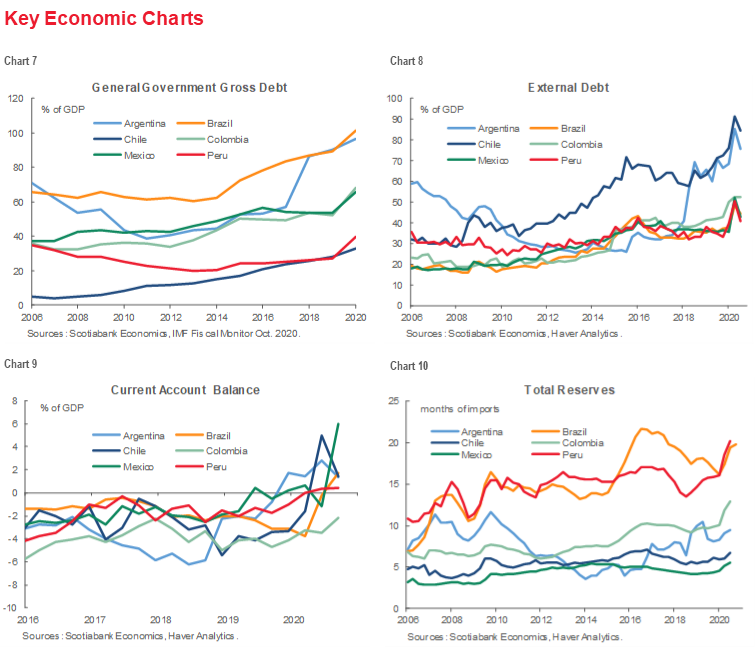

Every country is pinning hopes on vaccinations to stem COVID-19 second waves and bring the pandemic to a close before a third wave begins rising, but the prospects for vaccines in Latam need to be given some context. As we noted in the February 2 Daily Points, companies’ own projections of total vaccine production in 2021 are consistent with potential coverage of up to 78% of the world’s 7.7 bn people, adjusted for vaccines that require two doses per person (chart 10). Even with potential delays, this is still a very positive outlook considering that we didn’t have any immediate vaccine prospects prior to November’s initial trial results.

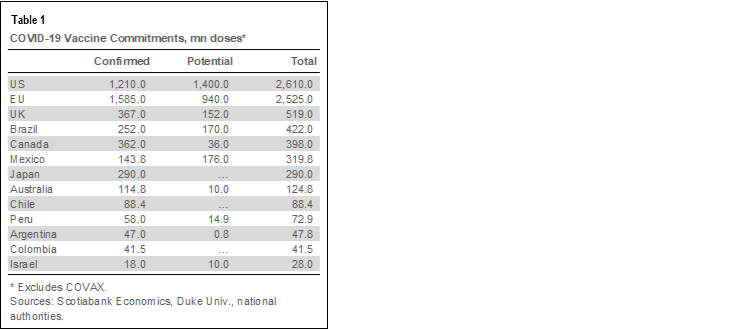

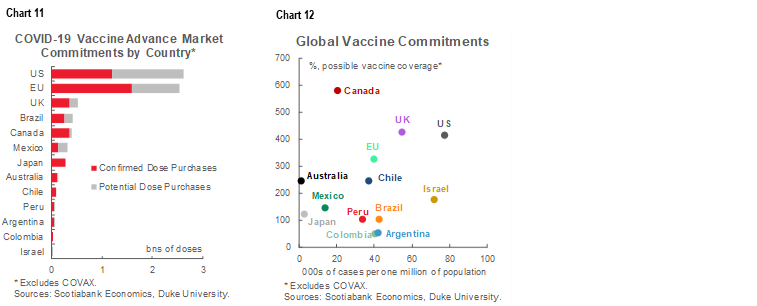

The existing and likely distribution of vaccine doses is likely to be skewed for an extended period of time. Industrialized country governments have heavily over-committed to vaccine purchases (chart 11 and table 1), which is likely to delay vaccine roll-outs in emerging and developing countries. Canada, for instance, has earmarked purchases that would cover its total population nearly six-times over (chart 12). In a somewhat surprising move, Ottawa is even tapping some doses from the international COVAX initiative, which had been intended to ensure equitable access to vaccines for middle– and low-income countries.

Latam’s governments have made proactive efforts on par with other developed and emerging markets to purchase and option vaccine for their citizens (chart 11, again). In per capita terms, Chile is leading the region with confirmed and potential coverage of nearly 250% of its population (chart 12, again). On the other end of the spectrum, Argentina and Colombia have not yet made confirmed and potential commitments that would cover all of their residents. These commitment numbers are from Duke University Global Health Innovation Centre data banks, which are may differ from locally reported updates and official figures, but have the virtue of being internationally comparable; we have updated them, were possible, for breaking credible announcements over the last 24 hours. “Confirmed doses” refers to orders that have been signed and finalized; “potential doses” denotes deals that are under negotiation and not yet final, as well as options for additional doses under existing confirmed deals.

As every country is discovering, confirmed and potential vaccine commitments are a first step, but securing delivery is the next challenge. The first quarter of 2021 will see only an initial tranche of vaccine doses arriving in the Pacific Alliance countries under numbers reported.

- Chile. About 4 mn doses have arrived in the country with another roughly 6 mn doses due by the end of Q1 according to indications from the authorities. These

10 mn doses are equivalent to about 11% of total confirmed and potential doses ordered. The country’s mass vaccination program got underway on Wednesday, February 3. Oxford University data indicate that about 292k doses had been administered as of Thursday, February 4. - Colombia. The government’s vaccination program website indicates combined and potential vaccine commitments for 61.5 mn doses, around 50% more than the

41.5 mn doses total indicated in the Duke University data owing to the exclusion of 20 mn COVAX doses from the Duke numbers. To our knowledge, no doses have yet arrived in the country even though the government’s mass vaccination program is scheduled to begin on February 20. - Mexico. About 15% of its confirmed vaccine orders are set for delivery during Q1-2021, but when one includes the options that take Mexico’s potential coverage of its population to 148% (chart 12, again), only about 7% of its total confirmed and potential doses are scheduled to arrive by end-March. According to Oxford University data, about 695k doses had been administered as of Thursday, February 4; at the time of publication, we could not confirm how many more doses have been delivered to Mexico.

- Peru. About 1 mn doses had arrived in Peru by end-January, or about 2% of confirmed and potential doses. The government aims to have 15 mn people fully vaccinated by mid-2021, which would require a major acceleration in deliveries for this goal to be achieved. Pres. Sagasti announced on Thursday, February 4, new purchases commitments that move some doses from “potential” to “confirmed” status in the data outlined in charts 11 and 12, as well as table 1. As we noted in our February 5 Latam Daily, over 1.1 mn vaccine doses are set to hit Peru in February and at least 400k in March, with an accumulated total of 6.5 mn landing in the country by July. This outlook still puts the country on track to fall short of half of its mid-2021 vaccination goal.

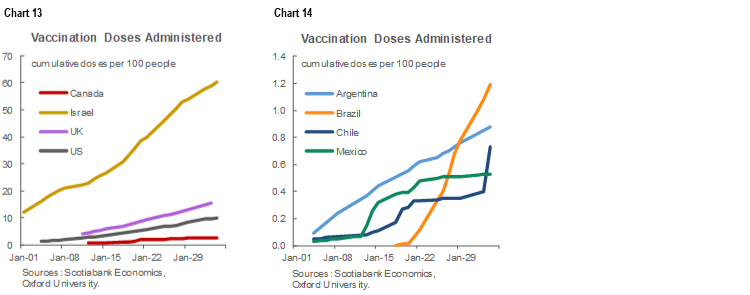

Emerging production delays and possible export controls at manufacturing sites will almost certainly push these dates and numbers back further into 2021 and 2022. As it is, vaccination administration in Latam substantially lags per capita progress in major industrialized countries (charts 13 and 14, respectively).

HERD IMMUNITY: NO MAGIC NUMBER

It’s highly unlikely that any major country in Latam will achieve “herd” or population immunity through a combination of contagion and vaccinations before 2022. As the WHO notes, the share of population that needs to be immune in order to achieve herd immunity varies with each disease—and can change over time for the same disease depending on circumstances such as degrees of social interaction and the extent of existing infection. For instance, the threshold for measles herd immunity is 95% and for polio it is 80%; we don’t yet know the herd-immunity threshold for COVID-19, but most models imply numbers around the 60–70% mark.

Estimates of herd-immunity thresholds are calculated using the basic reproduction number, R0, the number of cases, on average, spread by one infected individual in a population that has no pre-existing immunities. The calculation of the herd-immunity threshold, 1-1/R0, implies that the higher the R0 the greater the share of the population that needs to be immune to reach herd immunity. As a pandemic proceeds and more people get infected and gain immunity, R0 tends to fall and take the herd immunity threshold down with it.

Leading epidemiologists warn that herd immunity has never been achieved successfully by simply allowing contagion to run its course. Accelerated progress on vaccination delivery remains critically important to Latam’s economic outlook even in countries such as Mexico and Peru where up to 50% of the population may have already achieved immunity through infection.

Additionally, it’s important to keep in mind that the achievement of herd immunity likely won’t mark the end of the pandemic, a move to total re-opening of economic activity, and a full resumption of “normal” life free of restrictions. It’s not yet clear whether existing vaccines prevent re-infection and transmission of the novel coronavirus—what epidemiologists call “sterilizing immunity”—even if they are effective in stopping the development of either mild or serious COVID-19. Until we have better evidence on this question, we have to expect that the COVID-19 pandemic will remain a live issue, not just in Latam, but globally, well into 2022

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | carlos.munoz@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.