- Continued depreciation could trigger higher rates and other policy responses.

BCCH COULD BE FORCED TO CONTINUE RAISING THE BENCHMARK RATE

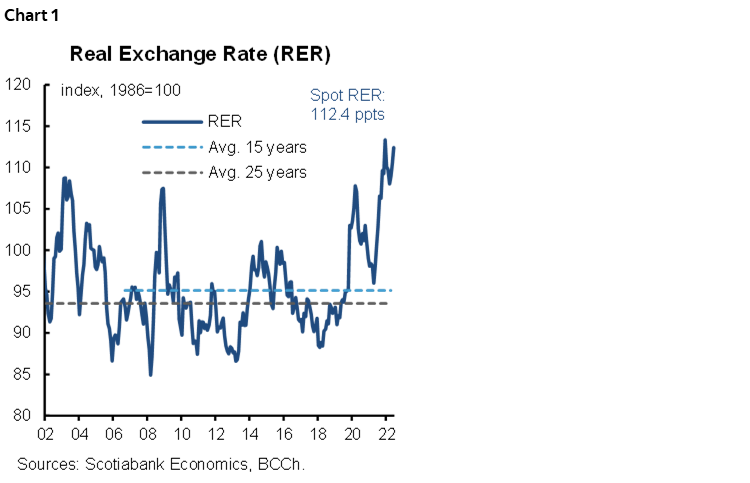

The Chilean peso (CLP) has experienced an almost secular depreciation against the US dollar since April 2022, recently exceeding CLP 880. For many, this reflects the appreciation of the US dollar in the wake of an accelerated rate of policy normalization by the Federal Reserve. In our view, however, there is an idiosyncratic component in the CLP depreciation that is evident in a real exchange rate (RER) that in June reached its second highest level since the floating exchange rate regime was implemented in 2001 (chart 1). We estimate the RER around 112.4 points in its base measure (1986=100), just 1% below the level reached in December 2021 in the middle of the second presidential round, despite the increase in external prices and recent records of high inflation.

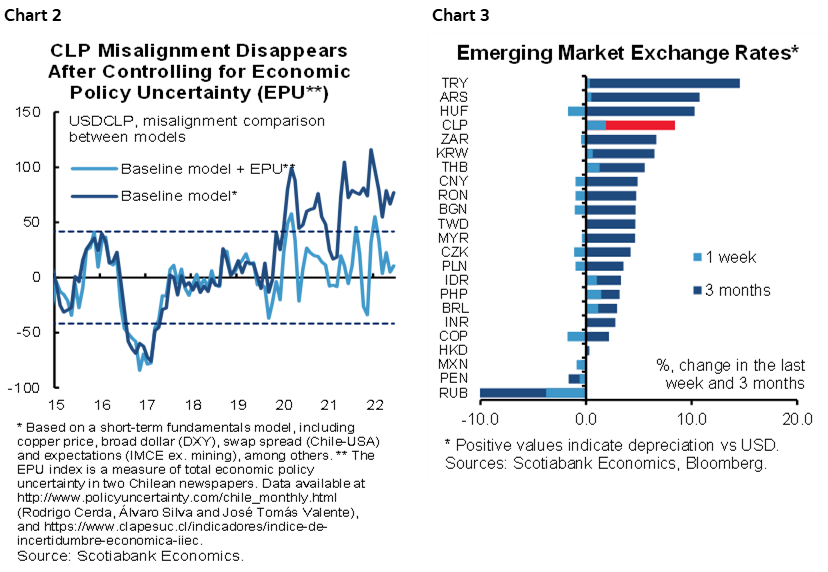

The depreciation of the CLP goes beyond external factors, and is driven by higher domestic political uncertainty and portfolio balance factors. Simple models to determine the CLP point to a misalignment since the October 2019 (social unrest) of between CLP 70–100 with respect to traditional determinants. More recently, the CLP has been subject to an increased level of misalignment, even after controlling for political uncertainty (chart 2). In fact, the misalignment becomes evident when we observe that the CLP is among the currencies with the greatest depreciation against the US dollar in recent days (chart 3).

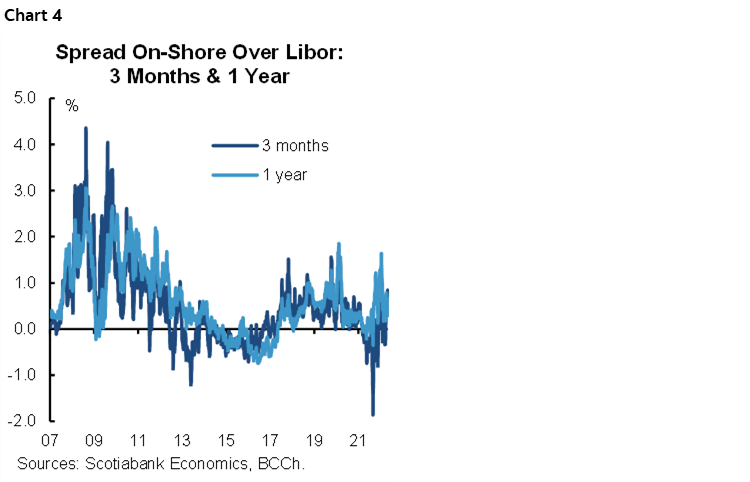

CLP depreciation has not been accompanied by short-term liquidity problems as in the past. The on-shore spread with external interest rates remains stable for all terms (chart 4), suggesting that the CLP depreciation is not responding to the absence of foreign currency or exchange rate mismatches. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that, prior to the exit referendum for the new Constitution on September 4, there may be episodes of foreign currency illiquidity that may require central bank intervention to avoid the undesired increases to the cost of sovereign financing.

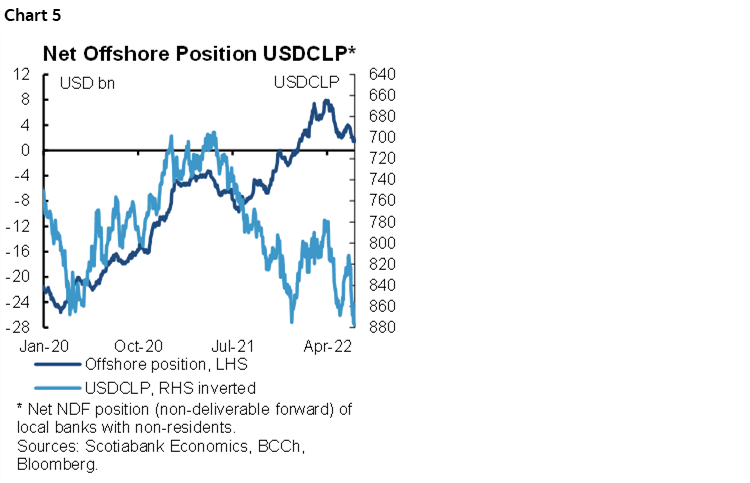

Meanwhile, pension fund administrators (AFPs) are not cushioning the unwinding of carry trades (chart 5). Short-term foreign investors have been betting in favour of the CLP since the beginning of 2020. With some temporary easing, the NDF position was in positive territory earlier this year, but since April it has started to unwind, coinciding with a more aggressive stance by the Fed regarding the evolution of inflation. This unwinding, which brings with it the purchase of USD forward, has not been contained despite the improvement in the interest rate differential. Equally worrisome has been the diminished buffering role of AFPs that have not been big sellers of USD in the face of a modest shift in contributors to conservative funds. A similar phenomenon, although somewhat more intense, occurred after the social unrest, where external and local movements towards the purchase of USD (spot and forward) exacerbated the depreciation of the CLP.

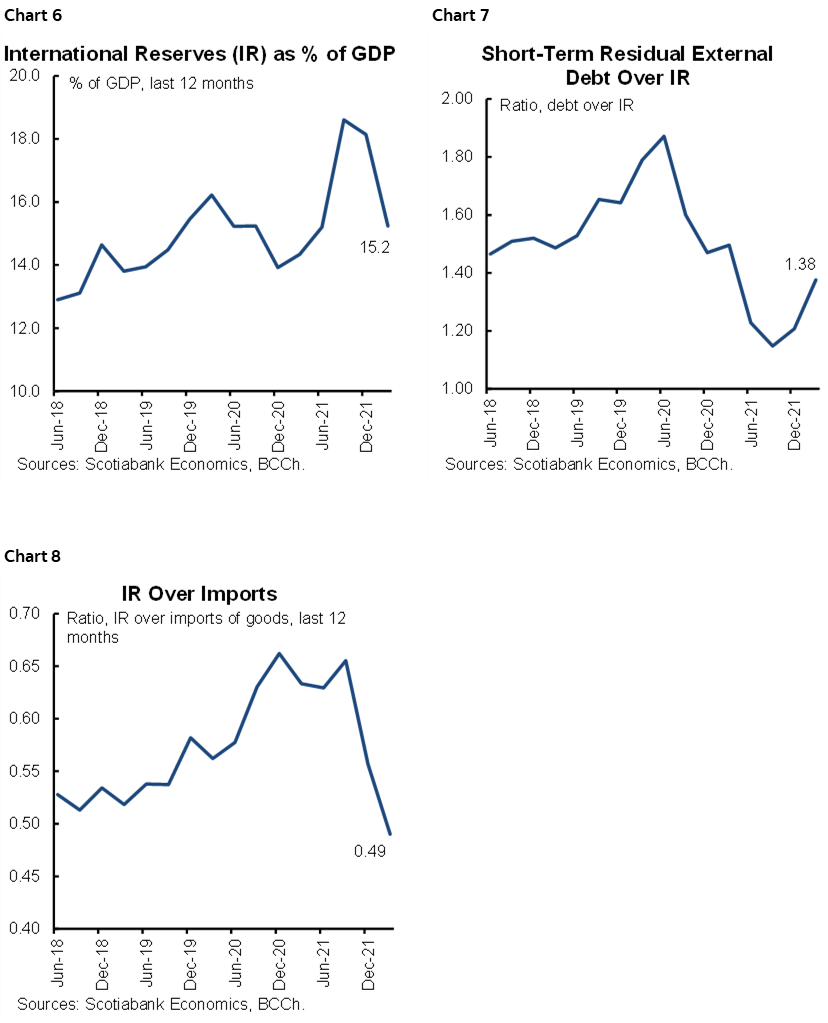

Arguments have already been made in support of foreign exchange intervention or other measures to mitigate the idiosyncratic depreciation of the CLP. However, the success of these measures is not assured. Traditional indicators to assess the adequacy of international reserves (IR) give mixed messages, albeit with a slight positive bias. In terms of IR/GDP, at a ratio of around 15%, the situation looks somewhat better than that observed before the pandemic after the IR accumulation process (not completed) carried out by the central bank (chart 6). Meanwhile, thanks to better sovereign debt maturity management (liability management) together with a lower intensity of corporate and banking external indebtedness, the situation with respect to Short-Term Residual External Debt looks favourable, with an index of 1.38, below what was observed in the recent past (chart 7). That said, international reserves look low compared to imports. In fact, given the strong rebound in consumption, which has led to a significant increase in consumer goods imports and higher imports of capital goods, the ratio is below the levels observed in the last 4 years (chart 8).

There are insufficient reserves to conduct a large-scale intervention in the event that the central bank opts for a direct sale of dollars in the spot market. A sale of USD greater than USD 10 bn would leave international reserves particularly low. Consequently, such a strategy could only lead to short-term appreciations of the peso, given the lack of credibility in the firepower. Alternatively, an intervention targeting the idiosyncratic component of the CLP depreciation, with a sale of between USD 5–10 bn accompanied by micro or macroprudential policies that discourage dollarization, could have impacts that are more favorable.

In our view, if the CLP depreciates towards 900–920 through end-June, the central bank would likely move faster than expected for the next July’s monetary policy meeting in raising rates and implement a foreign exchange intervention coordinated with the Ministry of Finance (micro/macroprudential measures). In this scenario, we do not rule out an accelerated USD liquidation process to finance the fiscal spending committed for the rest of the year.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.