Global auto sales are starting to normalize in August following three consecutive months of acceleration. On a month-over-month basis, global purchases contracted by -4% (sa). On a year-over-year basis, sales were down by -15% y/y before adjusting for seasonality, which may overestimate the slowdown as August contained two fewer selling days in most markets.

This pales relative to the robust 22% m/m (sa) pick-up in July sales—but not alarmingly so—suggesting rather that the immediate impacts of pent-up demand are starting to wear off. Global sales are down by -24% ytd.

Chinese auto sales posted a modest -3% m/m (sa) retreat in August. Sales appear to have more or less stabilized over the summer months following the very strong rebound between March and May that propelled sales into positive territory on a year-over-year basis. Year-to-date sales sit at -15%.

The sales rebound in Japan similarly slowed with a -3% m/m (sa) decline that translated into a -16% y/y decline for the month. Weaker activity in China and Japan was very modestly offset by improving sales in India and Indonesia, albeit from very low levels.

European auto sales pulled back in August for the first time following three months of accelerating month-over-month sales. Western European sales, for example, were down -14% m/m (sa)—or -15% y/y— driven by slowdowns of similar magnitude in its key markets such as Germany and France.

US auto purchases saw a fourth month of increased activity since April with sales expanding by 4% m/m (sa), but down by -19% y/y. A four-month rebound is exceptional relative to other major markets, but the US sales trough was much shallower than in other major markets while the strength of its rebound is weaker.

Canadian auto sales lost some steam in August with a -7% m/m (sa)decline (or -9% y/y). A more fulsome take on Canadian and US August sales is found here. With September data imminent, Labour Day weekend sales are likely to show some strength in Canadian and US sales activity, but both are expected to normalize in the months ahead.

Latin American economies posted mixed results in August auto sales but, overall, sales were relatively flat. The summer rebound appears to be waning with Mexican auto sales slowing by -1% m/m (-29% y/y), Brazil by -3% m/m (-25% y/y), Colombia by -17% m/m (-44% y/y), and Peru by -1% m/m (-41% y/y). Chilean sales defied the regional trend, surging by 41% m/m (but were still down by -42% y/y). South American regional sales are down by -37 ytd, with Mexico only slightly better at -31% ytd as these economies never really experienced a flattening of pandemic curves over the summer.

In our baseline, global auto sales are expected to stabilize around more normal ranges of monthly variability as the pop from pent-up demand has largely been exhausted. This is consistent with other economic indicators such as job growth and retail sales where numbers are starting to normalize.

That said, there are still plenty of risks on the horizon for the remainder of the year as second waves are overtaking most major markets, policy supports are starting to sunset in many countries, and pending elections in the US threaten to upend markets.

We have not revised our outlook for 2020 (-20%), but flag near term developments that we are watching carefully in this issue.

1. WILL SECOND WAVES STALL THE AUTO SALES REBOUND?

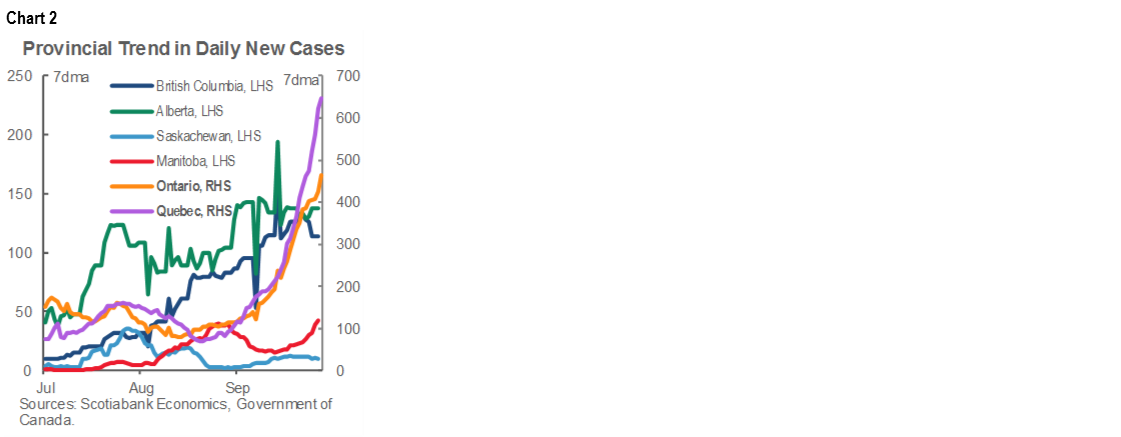

While re-openings around the world in the spring fueled early economic (and auto sales) rebounds that continued playing out over the summer months, a resurgence of COVID-19 in many countries could stall the recovery. The US curve never truly flattened and cases are expected to continue to surge this fall, while many European countries are experiencing second waves. Latin America—notably Brazil and Mexico—struggled to control the spread over the course of the summer. Curves flattened in Canada, but cases are starting to tick-up across most provinces from Quebec westward (chart 2) with Canada’s health agency raising alarm about a possible rapid escalation in cases. Ontario has already announced a “second wave” is official.

Our economic baseline (September 3rd) assumes that the virus will be circulating over the course of the fall and winter, but that measures to control outbreaks will be more targeted than the broad-based shutdowns in the spring. Consequently, we would not expect the unprecedented economic contractions witnessed around the world in the first half of the year (chart 3) that forced shutdowns across all activities, leading to extensive and broad-based job losses. However, a second wave would reinforce the unevenness of the recovery across sectors, particularly for those deemed higher-risk, while it could also slow the recovery through confidence channels with an escalation in uncertainty.

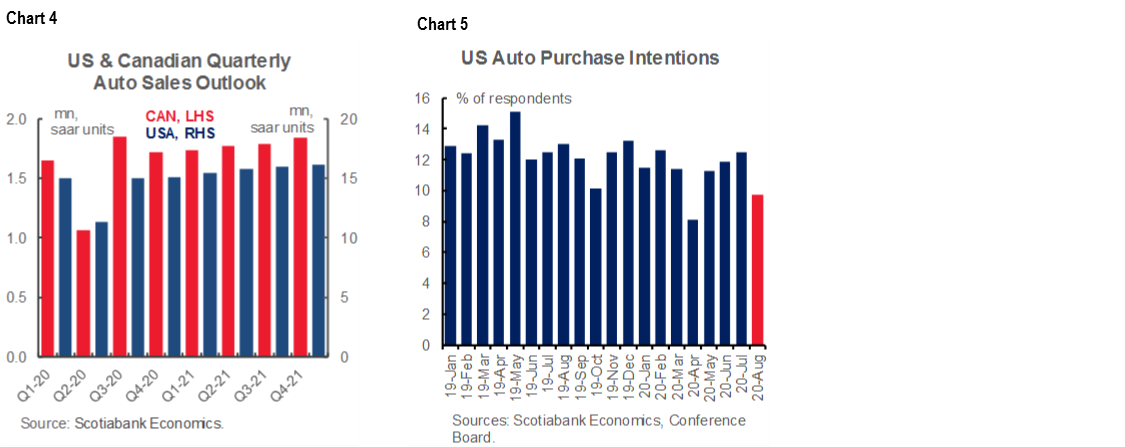

In this baseline scenario, auto sales would decelerate into the fall months mostly on the basis of pent-up demand having worked through the system over the summer months (chart 4). Heightened uncertainty from a pandemic resurgence would weigh further on what was already deemed to be a multi-year recovery as consumers hold back on a precautionary basis. Evidence from the first wave in many countries shows that households changed their behaviours and spending patterns well before governments imposed lockdown so it is possible that second waves trigger some of this restraint once again even if lockdowns are avoided. In the US, even though early August indicators including jobs were solid, while July hand-offs in retail and housing were strong, there was already a weakening of consumer sentiment with respect to future auto purchases (chart 5). Admittedly, the prospects of fading income supports could be affecting sentiment, as discussed later.

Otherwise, broad-based shutdowns would have a more serious impact on the auto sales outlook. Mandatory shutdowns of auto dealers in the spring drove monthly declines in the order of -80% y/y at the peak, whereas even in less stringent shutdowns (e.g., the US), sales declines were in the order of -50% y/y. It would not be unexpected in such a scenario of second waves where broad-based shutdowns are again implemented that global auto sales would face a second dip in sales—or essentially a “w-shaped” profile.

Some of the downside in both the base-case and worst-case scenarios could be offset by several factors. For one, the strength of the Chinese auto sales rebound, coupled with its capacity to tamp out new outbreaks (though not necessarily fully replicable in democratic countries), would likely soften the blow to global auto sales as it is already doing. Under our baseline, Chinese auto sales will contract by “only” -11% versus our forecast for the global auto sales contraction at -20% for 2020.

Second, many auto dealers ramped up their capacity to operate more flexibly in a pandemic-context. This should put them in a better position to continue to operate under second waves while offering options to health-concerned customers. For example, a recent survey by the Ontario Motor Vehicle Regulator (OMVIC) indicated that 46% and 38% of new and used car shoppers did not test drive the vehicle before making their purchases during COVID-19. This suggests consumers may be more flexible in the purchasing process, though 19% signalled they would still like to see more safety measures at dealerships. Nevertheless, in the same survey, dealers indicated that the biggest driver for future sales will be improved consumer confidence in the economic recovery so safety measures alone would not fully compensate.

2. WILL NEW ROUNDS OF FISCAL STIMULUS UNDERPIN THE RECOVERY?

Massive waves of fiscal (and monetary) support have helped prop up economies around the world and avoid an otherwise worse economic contraction. The IMF estimated global spending in the order of USD10 tn in its June round-up. In some major economies, fiscal support exceeded household income losses, part by design, part by luck. In Canada, for example, government transfers to households in the second quarter (i.e., May–June) were estimated to be in the order of $50 bn, while aggregate household income losses were around $20 bn (chart 6). Not surprisingly, Canada’s household savings rate shot up to 28% (from pre-crisis levels of around 2–3%) in that same quarter (chart 7).

This was not typical ‘precautionary savings’ behaviour. It is common in typical recessions to see households save as confidence wanes. In this crisis, this may have been one factor, but arguably has been overshadowed by generous government transfers and substantial tax and loan deferrals, coupled with an inability to consume during the lockdown. These factors likely underpinned the faster-than-anticipated rebound in retail sales across the board in many countries. Retail spending in both the US and Canada, for example, surpassed pre-pandemic levels in July (chart 8). Auto sales would have been riding this retail rebound, and we are likely to see third quarter household savings drawn down when data is available in Canada, while the more recent data from the US is already starting to show unwinding in July (chart 9).

With the early recovery decelerating around the world, those countries that provide fresh rounds of stimulus may experience softer landings. Canada has sunset its income support (the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, aka the CERB), but announced a 1-year CERB-like benefit at the end of August. It now provides an equivalent weekly amount (e.g., $500) for up to 26 weeks, while the recipient can earn up to $38.4 k in annual income before a claw-back in benefits starts. As we have argued here, this should provide continued support to the recovery, provided there are no broad-based shutdowns. There will still likely be a normalisation in retail spending as the pop from shutdowns is exhausted with data already showing this in Canada. This should support a continued recovery in Canadian auto sales with a more normal range of volatility over the next few months for end-of-year sales around 1.6 mn units. The renewed fiscal support (and possibly more to come) puts more upside on this number.

However, the fate of additional US fiscal stimulus is in a precarious position. Employment benefits (USD600/week) expired at the end of July. The Republicans have tabled a bill to reduce this to USD200, while the Democrats would keep it whole. Not surprisingly, the two differ substantially on the size of an overall package: USD500 bn versus USD2.4 tn. With elections pending, it is increasingly unlikely that this will be passed in the near term. While unemployment claims have been trending downward, this may nevertheless curb the recovery with Fed Chairman Powell roiling markets last week with a statement to that effect.

3. WILL SUPPLY CONSTRAINTS MATERIALLY IMPACT SALES?

A slower recovery in auto production continues to create supply pressures with inventories at all-time lows. North American auto production achieved positive year-over-year growth in July as automakers canceled summer downtime; however, according to Ward’s Automotive, activity dipped again in August (-6% y/y). Production still trails the rebound in demand, particularly for sought-after models, with tight inventory expected to persist through the fall. North American light vehicle sales tallied 7.6 mn units between March and August, whereas production stood at 5.2 mn. While this is not a one-for-one, it gives a sense of the trend.

Dealers are reporting challenges with tight inventory. In the aforementioned OMVIC survey, 78% of Ontario dealerships reported difficulty obtaining vehicles (new and used), while 26% ranked supply as the biggest driver to future sales (after improved consumer confidence and financing conditions). On a brighter side, only 7% of car shoppers in the survey indicated that their desired vehicle was unavailable.

There is still potential for further supply disruptions in the fall related to the pandemic, either in OEM facilities or supply chains. However, again, much has been learned in the first wave that should minimize the overall impact. Meanwhile labour negotiations in Canada are off to a smooth start with an agreement just ratified between UNIFOR and Ford. This reduces one supply risk that had been looming following last fall’s supply disruptions owing to stalled labour negotiations in the US that resulted in GM strikes.

Longer term, we do not expect broad-based re-shoring of auto production and supply chains as a result of the pandemic. The exception may be for strategic sectors such as medical equipment, though for the auto sector, there was already some re-shoring in production to the US set in motion as a result of the USMCA agreement last year, along with the threats of further actions towards other countries and regions around the world. With trade policy likely to pivot more positively under a new Presidency, the effects of the pandemic are more likely to fuel a re-think around inventory management and supply chain diversification for greater resiliency to future shocks rather than a broad-based retreat from globalization.

4. HAS THE PANDEMIC CREATED NEW DEMAND FOR VEHICLES?

Pent-up demand was clearly a factor behind the initial rebound in auto sales around the world as dealerships re-opened following the shutdowns. But the strength of the rebound in countries including Canada, the US, and China surprised many observers, particularly as auto sales had been anaemic in most major markets heading into the pandemic and auto sales recoveries in past recessions have been multi-year.

Consumer intention surveys are pointing to potentially new demand creation as a result of the pandemic including fears of using public transit and ridesharing services. Polling by CarGurus in the US and Canada over the summer, for example, showed over one in five purchase “intenders” indicated they had not planned to buy a vehicle prior to the pandemic. An August survey by AutoTRADER.ca reported that first-time car buyers in Canada are three times more likely to state they’re purchasing a vehicle because of the pandemic, while one in 10 respondents indicated their decision to buy was a direct result of the pandemic. An intention to purchase does not translate one-for-one into an actual purchase, but it signals interest in the right direction.

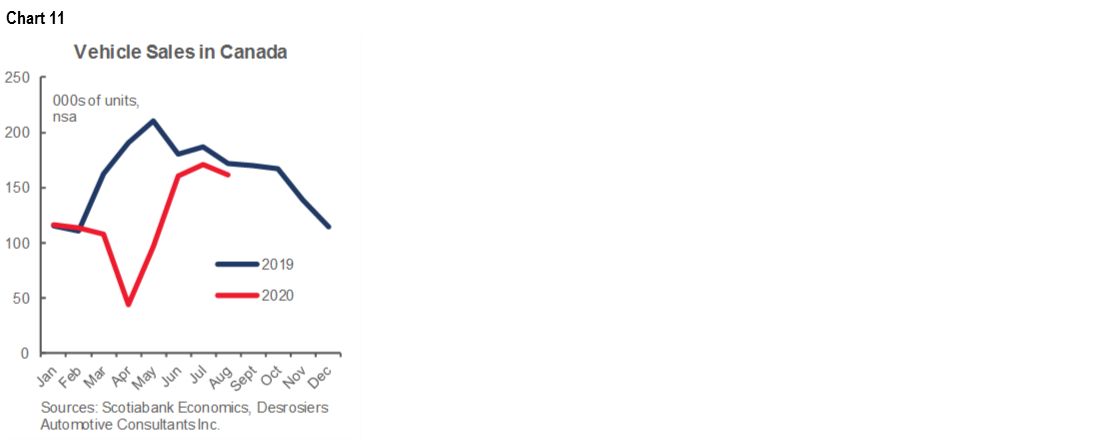

This provides some upside to the global auto sales outlook, but it would be premature to suggest a structural shift in demand at this point. Monthly sales are settling back to more ‘normal’ ranges already (chart 11) as the effects of the shutdown are now behind us. Even when fleet sales activity is netted out from total sales, retail sales activity now sits at comparable levels to a year ago. The pace itself is remarkable and has clearly been underpinned by substantial government transfers to households, as well as tax and loan deferrals, and lower costs of financing in most markets—including the US and Canada. This makes it difficult to tease out the role that pandemic-fears may have played in purchases at this stage. Furthermore, the pandemic will pass eventually and comfort levels with other modes of transit should improve with time.

Other pandemic-induced changes in behaviour could work in opposite directions over time. With air-travel substantially depressed, households are relying on vehicles for vacations or more generally opting for travel by vehicle over rail or air. A recent survey by Cooper’s Tires reported that over 2 in 5 Americans took more road trips this summer while almost half reported relying on their vehicles more in general as a result of COVID-19. On the other hand a permanent increase in work-from-home could reduce mileage but this could be accompanied by a shift towards household relocations to more affordable suburban areas where vehicle ownership is often necessary. Needless to say, the net impact is guesswork at this stage, but at a minimum, behavioural impacts are likely positive for now and will likely remain so for as long as the pandemic is around.

5. WILL THE PANDEMIC BE A BOOM OR BUST FOR ELECTRIC VEHICLE SALES?

The answer is mostly ‘it depends’ in the near term. Electric vehicle sales in China and Europe stand to benefit from pandemic-related incentives along with supportive policy and regulatory environments prior to the pandemic. In China, EVs were exempt from the 10% sales tax early in the pandemic (though clarity for Tesla eligibility was only confirmed in late August). It also delayed the sunsetting of EV production subsidies for Chinese OEMs until 2022. Germany has doubled its EV purchase incentive, while stricter emissions regulations that pre-date the pandemic are also pushing manufacturers to deliver more affordable models. McKinsey estimates that EV market share will actually increase as a result of the pandemic in these markets with China growing from 5% of new sales (2019) to 13% in 2022, while Europe is expected to grow from 3% to 14% in the same period, both modestly higher than pre-pandemic growth forecasts.

On the other hand, the US EV market is expected to face headwinds from the pandemic. Lower gas prices, along with a less stringent regulatory environment will favour internal combustion engines in the near term. McKinsey’s baseline forecasts put US EV’s on a modestly slower growth trajectory (from 2% to 6% between 2019 and 2022). Unlike European production trends, US manufacturers have been delaying EV production through the pandemic to ramp-up ICE vehicle production.

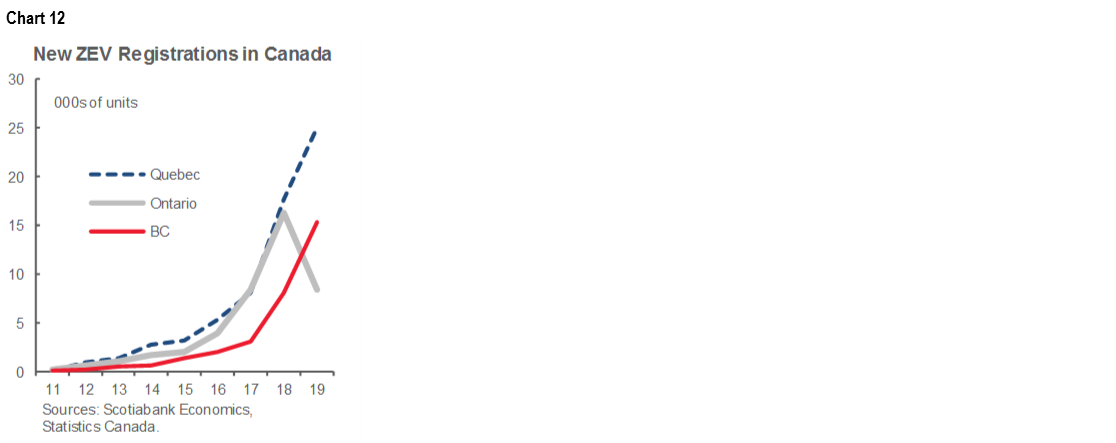

The global EV outlook has suddenly become interesting for Canada. The Canadian EV market is relatively small. At 3% of total sales in 2019 (or 50 k units for Zero Emission Vehicles, chart 12), this is a decimal point in the global outlook with the McKinsey forecasts putting the three major markets (i.e., China, Europe, and US) at almost 7.3 mn vehicles. While data is limited, preliminary estimates suggest mid-year EV sales in Canada may be modestly north of 3%—essentially holding their ground despite higher sticker prices as wealthier households have been less impacted by the pandemic.

Ford Motor Company’s recent announcement that it plans to build five EV models in Canada (with $500 mn in support from the federal and Ontario governments) should re-invigorate Canadian interest in domestic and global EV markets. The federal government has set ambitious targets (10% of all new sales by 2025, 30% by 2030, and 100% by 2040). With initial funding allocations for purchase incentives almost exhausted, the recent Speech from the Throne promises more, while it would be surprising not to see the Ontario government reinstate its incentives that were cancelled last year now that the province has skin in the game.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including, Scotiabanc Inc.; Citadel Hill Advisors L.L.C.; The Bank of Nova Scotia Trust Company of New York; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Limited; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa S.A. de C.V., Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorised by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., and Scotia Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.