- Economic growth is slowing but a traditional recession is likely to be avoided. The Canadian economy is clearly slowing as past interest rate increases bite, but the US economy remains very resilient. As a result, we have shaved our expectations for Canada to 0.5% in 2024 but raised our forecast for US growth to 1.3%.

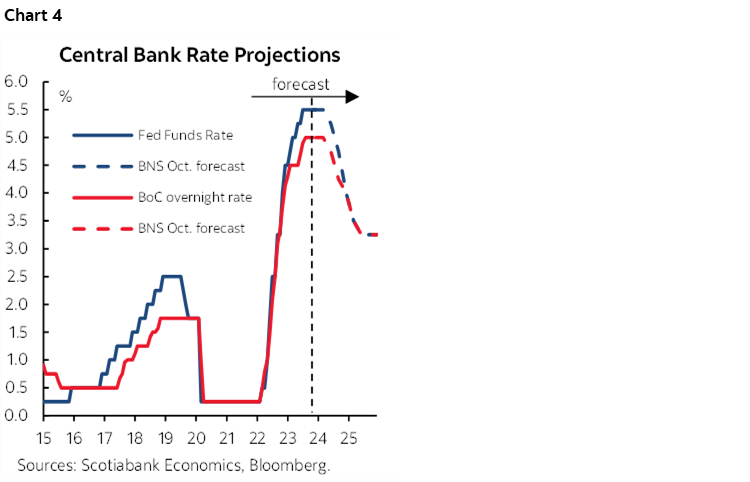

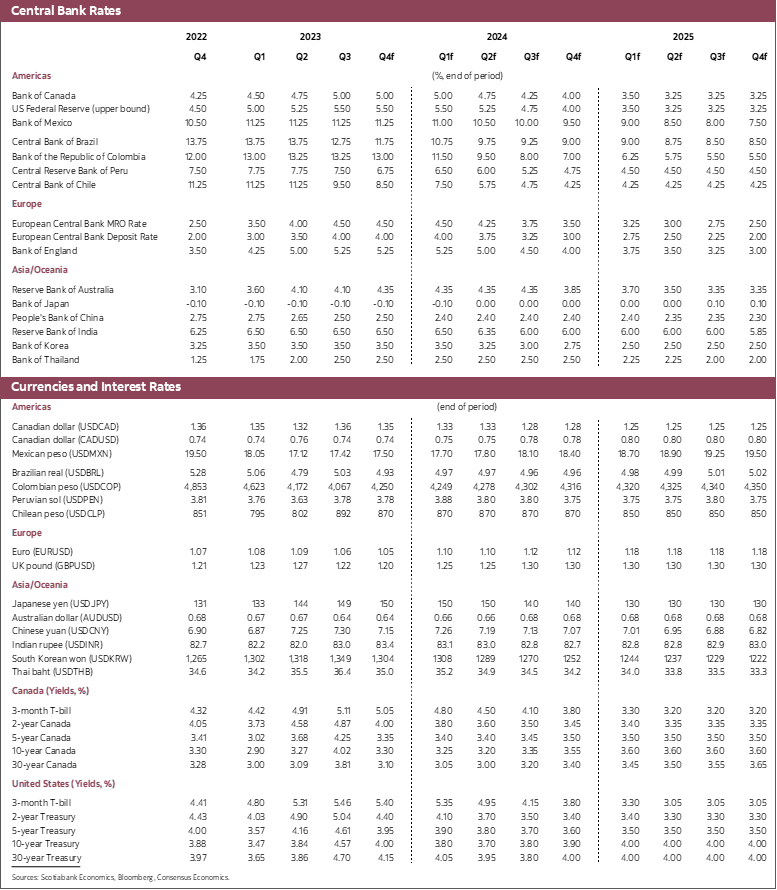

- We expect the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates by more than the Bank of Canada next year despite the former’s better economic performance. From mid-year to end 2024, we think the Bank of Canada will cut its policy rate by 100 bp and that the Federal Reserve will cut by 150 bp.

- The larger cuts in the United States are prompted by a much better productivity performance, which is allowing that economy’s substantial wage gains to be less inflationary than in Canada.

From an economics perspective, the two key questions for 2024 are: how fast will rates come down and will the United States or Canada experience a recession? Uncertainty around these questions will likely cloud decisions and impact risk appetite until more clarity is available on these issues. Our view is that both economies will experience the equivalent of an economic stall in the first half of 2024 but avoid a full-blown recession. Inflation is under better control in the United States than in Canada and we think this will lead the Federal Reserve to cut rates by 150 bp starting in mid-2024. We expect the Bank of Canada will cut rates 100 bp in Canada over that same period.

The U.S. and Canadian economies have been remarkably resilient in light of the sharp tightening in monetary policy. The result of that tightening, and the focus of many doomsayers, is that rates are at 5% in Canada and 5.5% in the United States. There is no question that rates at these levels are causing a slowdown in activity. There is also no question that monetary drag will build in 2024 as the full impact of rate increases is felt, not only because of the lags in the transmission mechanism, but also because real policy rates are rising as inflation moderates. The question is whether this level of rates will trigger a recession or allow economies to land softly.

Our view continues to be that economies will land softly (chart 1). The fact that rates are where they currently are reflects an underlying resilience in economic activity that should provide a cushion against more damaging outcomes. The causes of this resilience differ across the border. In the United States, balance sheets remain reasonably strong for both firms and households, but the real source of resilience over the last year has been fiscal policy. The government cyclically adjusted primary deficit in relation to potential output for the United States rose from an estimated 3.1% in 2023, as published by the IMF in October 2022, to 6.0% in the most recent estimate. In other words, the fiscal impulse increased 3 percentage points of potential GDP in a year (chart 2). That is massive fiscal support for an economy that the central bank is trying to slow. Thankfully, that impulse will diminish in 2024, but fiscal support will likely remain substantial in the United States, with an expected cyclically adjusted primary deficit in relation to potential output of 4.7%.

Looking at dynamics beyond the fiscal impact in the United States, strength in the second half of 2023, notably on the consumer spending side, suggests more momentum going into 2024 than earlier assessed and we have revised our US forecast for 2023 and 2024 upwards accordingly. Moreover, with productivity surging in the United States, we have also raised our estimate of potential output growth—the effective non-inflationary speed limit of the economy—to 2.2% from 2.0%. The more data come in, the less likely a recession seems. This is despite evident weakness in measures of economic sentiment, which are very much at odds with recent economic data.

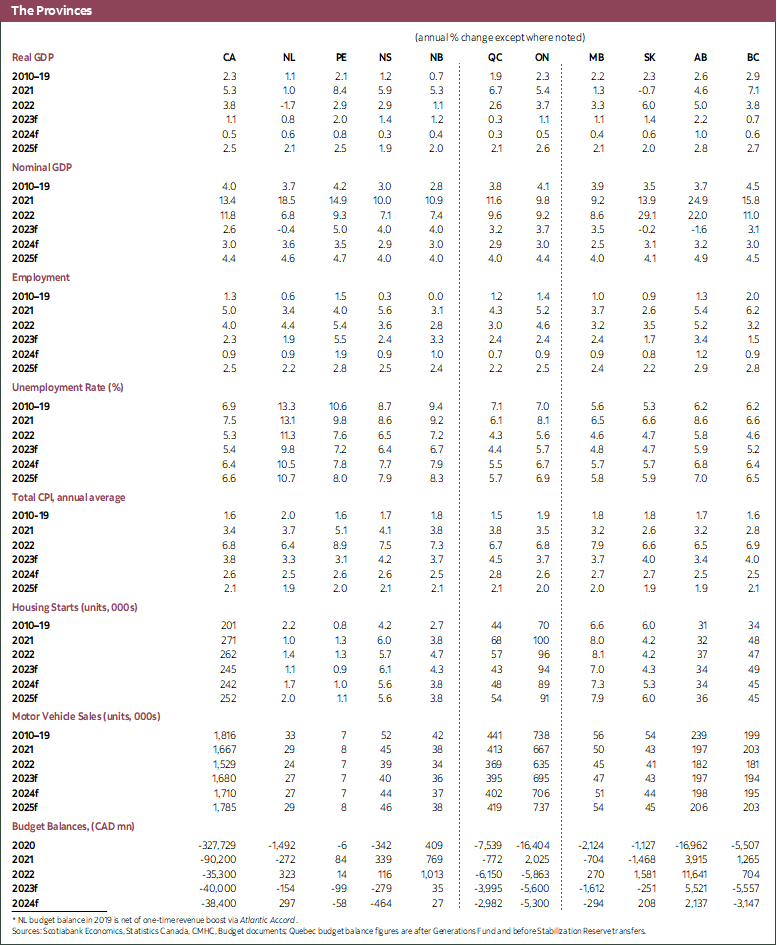

The growth slowdown appears more certain in Canada than the United States. There is clear evidence of mounting, though still modest, financial stress on households. The Bank of Canada’s 475 bp of increases so far are contributing to a modest slowdown in consumer spending, but the impact of higher rates is most evident in the housing market and spending categories associated with that. Despite that slowdown, our estimates suggest there is still a fair amount of pent-up demand from households, which points to a less aggressive curtailing of household spending than seen in earlier rate tightening cycles. That, in conjunction with still reasonably healthy household balance sheets and a record pace of population growth, suggests material downside risks to Canadian household spending are overblown. In addition, job vacancies remain somewhat elevated, leading firms to hire at a strong pace through the most recent data prints. Business spending is softening along with sentiment, leading to lower investment. Business investment should be a drag on activity in coming quarters.

There is lots of angst among some observers regarding the possibility of a hard landing or proper recession in Canada. We don’t subscribe to that perspective, in part because of the reasons previously discussed. Much of the concern from those with a more negative assessment hinges on the interaction of current mortgage rate levels with a surge of mortgage renewals expected in 2024 and 2025. As mortgages reset at rates that are multiple percentage points higher than at origination, there will unquestionably be an impact on household spending. We believe most households will have a high degree of control over the extent of the payment shock given price appreciation since mortgages were undertaken, allowing households to refinance and extend amortizations if they would like. Moreover, a third of mortgagees have accelerated payments by an average of $611 a month, according to Mortgage Professionals of Canada, giving even more flexibility to handle payment shocks. In addition, two-thirds of Scotiabank customers still have higher deposits than they did pre-pandemic. Assuming this is representative of typical Canadian households, there remains a substantial financial cushion to finance consumption expenditures. And finally, about 60% of households are either renters or have no mortgages on their properties. Again, there is no question that household spending will moderate going forward, but we find it hard to argue that the pullback in spending will be dramatic.

In Canada, two upside risks could lead to stronger-than-expected growth next year. The first upside risk is fiscal policy, where governments may undertake expansionary and/or direct support measures to firms and households during the upcoming budget season. The interaction of depressed sentiment and the challenging financial situation of many firms and households, combined with poor polling for the federal Liberals and many provincial premiers, mean this risk of additional fiscal support should not be discounted. The second upside risk concerns the housing market. That market is currently very weak given what is increasingly likely a peak in borrowing costs. The immense gap between supply and demand persists and is likely getting wider. We know that households are currently holding off purchasing decisions in anticipation of lower mortgage rates next year. As the expected decline in rates approaches, there is a chance that we see a repeat of the housing rebound seen in spring 2023 following the Bank of Canada’s rate pause. We are not forecasting this, but there does appear to be a meaningful probability that the spring housing market could rebound sharply if households act on pent-up demand for housing. If so, we could actually see an acceleration in the economy in Q1/24–Q2/24.

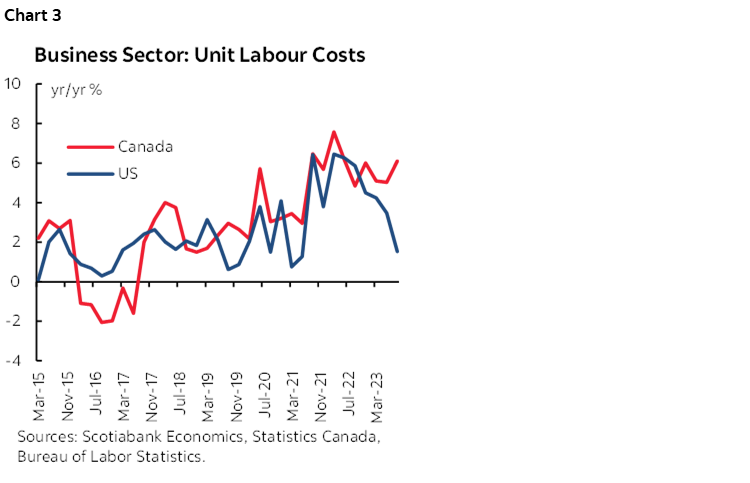

The key challenge in the outlook remains the future direction of interest rates. Any additional upward move in rates in either country will pose challenges for firms and households. In this respect, inflation outcomes will be critical to economic outcomes. In the United States and Canada, inflation has softened markedly in recent months. We believe there is more reason for inflation optimism in the United States than in Canada. The labour market remains significantly tighter in Canada than the United States, generating stronger wage gains north of the border. Combined with declining productivity in Canada and set against solid productivity growth in the United States, wage growth in Canada is substantially more inflationary than it is in the United States. This is very clearly seen in unit labour costs (chart 3). Recent wage prints in Canada are in the 5% area, whereas productivity growth is negative.

For these reasons, we expect the Federal Reserve will cut policy rates more aggressively than the Bank of Canada in 2024 (chart 4). We expect both to begin cutting around mid-year, though there is a risk that it could occur a bit earlier in the United States. At present, we forecast cuts of 150 bp in the United States and 100 bp in Canada. Naturally, the risks around the pace and timing of cuts centres on the evolution of the economic and inflation outlook. We are more concerned about upside risks to inflation in Canada relative to the United States given the problematic pace of wage gains in Canada. The Bank of Canada will have a lower threshold for further deviations away from the 2% target than the Federal Reserve. As a result, we remain of the view that over the next few meetings, the risks are greater that the Bank of Canada will tighten interest rates further rather than cut more rapidly. Further solidifying this view has been the sharp reduction in longer-term borrowing costs on both sides of the border, which is generating a substantial easing in monetary conditions at a time when neither central bank must think is appropriate.

The possibility of higher policy rates in the short run, as remote as that may seem to some, poses the greatest risk of recession in our view. Policy rates in Canada, in particular, are near the breaking point for firms and households. Additional increases resulting from stronger-than-expected inflation would extend the pain and could lead to much more weakness. There is hope, at the moment, among firms and households that rates have peaked and they will be cut. Dashing those hopes with higher policy rates could have nonlinear impacts on firm and household spending.

Political risks will loom large next year. Those in the United States are likely to be the most impactful. The U.S. presidential election could impart significant volatility on markets and the outlook. A second Trump presidency risks being highly disruptive to the United States and its trading partners. While the former president has not articulated much of a vision yet, he seems to support the idea of imposing unilateral tariffs on all imports into the United States, regardless of the county of origin. Several steps are required for this to happen: Trump would have to win the Republican nomination, which seems assured, then win the U.S. presidential election, which is more of a toss-up, and then implement this policy, which is far from assured. So, while this is a reasonably remote risk at present, it would be a high-impact development, with fundamental implications for the global trading system and the firms operating within it. And for a country like Canada that is particularly exposed to the United States, broad-based tariffs on exports to the United States would be highly disruptive.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.