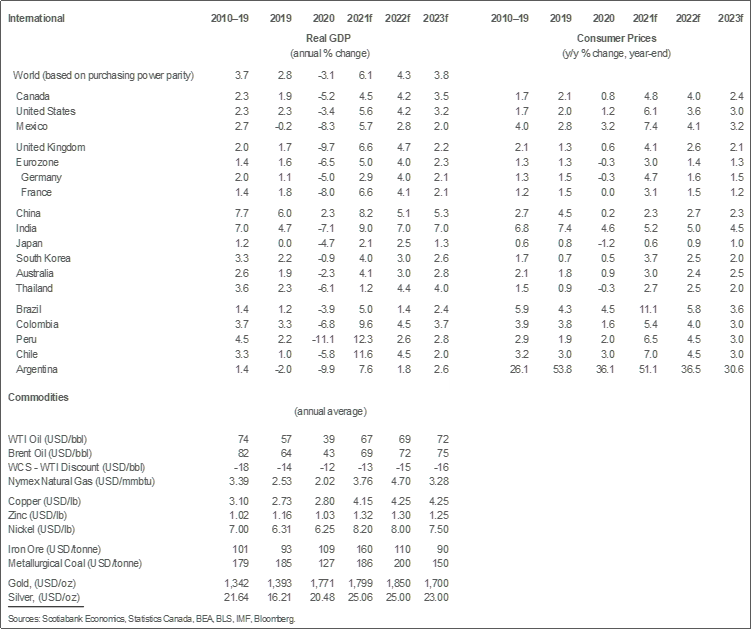

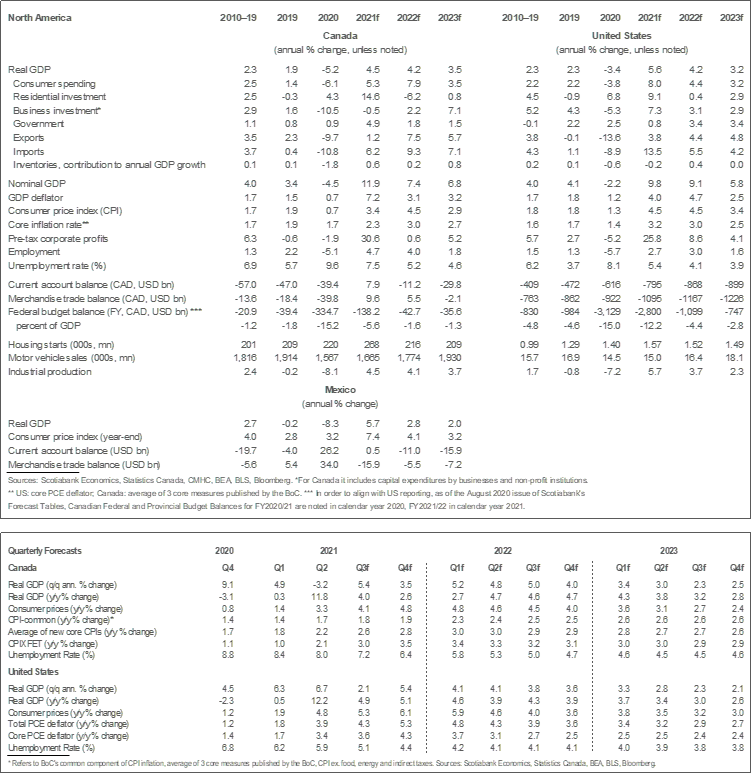

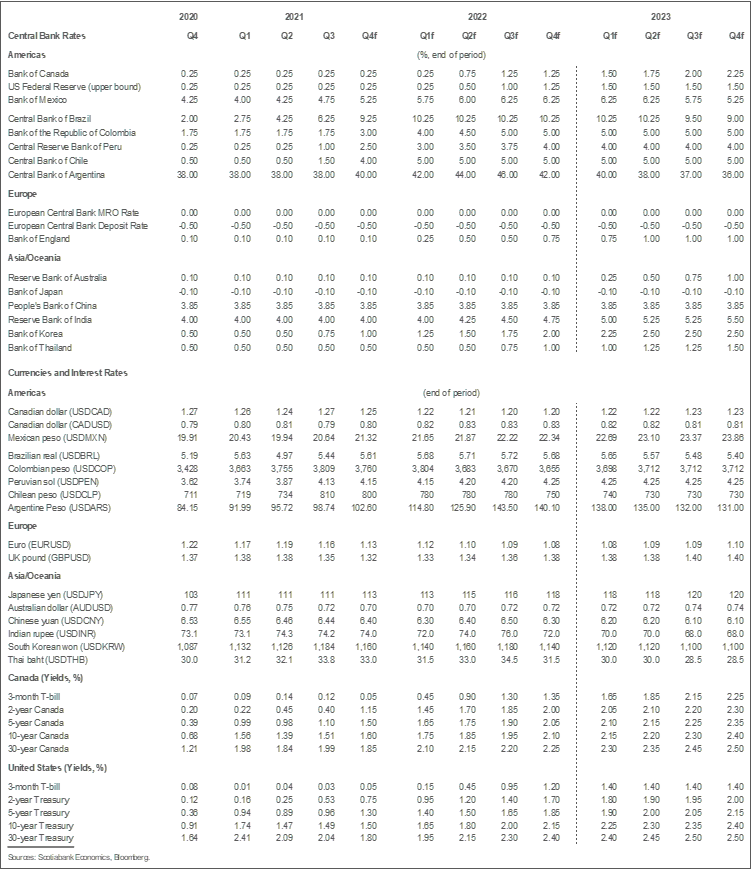

- Incoming data confirm a robust Canadian economy. With wages rising and upside surprises to inflation, we now believe the Bank of Canada (BoC) will raise rates in April, followed by three consecutive 25 bps moves in following meetings. A pause is likely late in 2022 to assess the impacts of the first set of moves. We remain of the view that 100 bps of tightening is forthcoming in 2022, followed by another 100 bps in 2023. The real policy rate would remain negative through the end of 2023.

- While emergence of the omicron variant increases uncertainty in the short-run, upside risks to the rate forecast dominate. We’ll be re-assessing our rate forecast once we have more clarity on the likely impacts of omicron.

- The review of the BoC’s inflation-control mandate clouds the rate and inflation outlook. Given the time it is taking to come to a decision on the 5-year review, we fear the Government and BoC are contemplating important changes to the mandate. If that were to occur, greater uncertainty would be introduced in the central bank’s reaction function with potential impacts on inflation expectations.

- The Federal Reserve is now clearly signalling concerns about inflation and appears to be paving the way for higher policy rates in the United States. We have brought forward our expected rate increases from late-2022 to mid-2022, with 100 bps of tightening expected in the year.

Major revisions to our United States and Canadian policy rate profiles are in order. In Canada, incoming data point to a very strong expansion in the final quarter of 2021 which, along with increasing evidence of an acceleration in wages, suggests the Bank of Canada will need to tighten in April instead of our earlier call of a first move in July. We are sticking with four rate increases in total for the year but will reassess that early next year as more information regarding omicron is available. In the US, Federal Reserve communications have shifted markedly in recent weeks to suggest more concern about the inflation outlook while also signalling a more aggressive tapering. As a result, we now expect the Fed to raise interest rates by 25 bps in June followed by another 75 bps of tightening by year-end, with a risk of an earlier launch to the hiking cycle. An explanation of these calls and the risks surrounding them follows.

The Governor of the Bank of Canada has made it clear for some time that the BoC would only raise rates when the output gap was closed, with his own prediction of that occurring in 2022-Q2 or Q3. Our earlier hesitancy to predict a move in April was largely conditioned on the view that Governor Macklem would have precious little hard evidence on economic activity in the second quarter by their April decision date. By April, only January GDP will be known but March employment data will be available, as will a series of less important indicators for the months of January and February. To move in April will require very strong conviction that the output gap will indeed by closed in Q2.

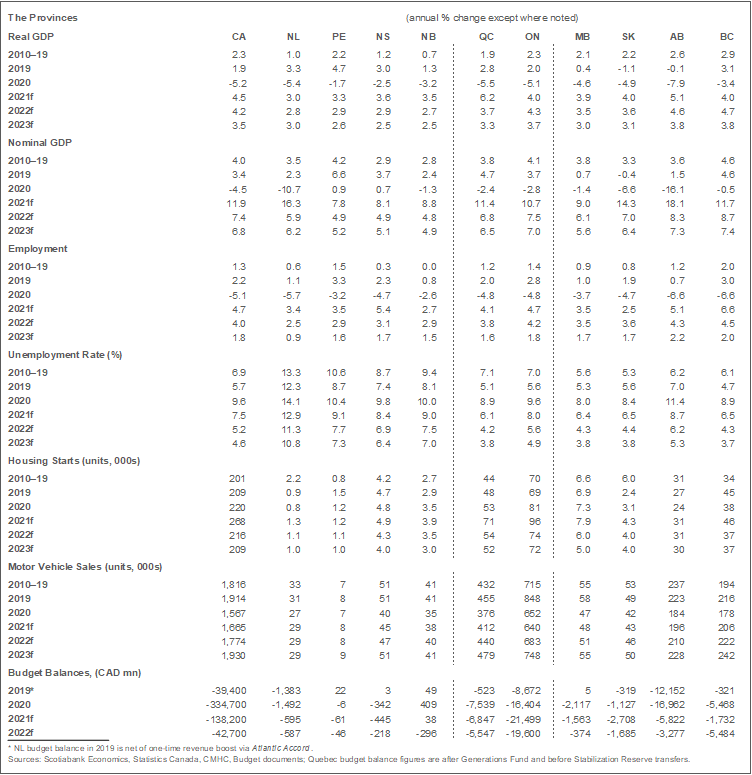

Incoming data for the final quarter of 2021 will be critical to that assessment. Statistics Canada guidance for October points to very robust GDP growth to launch the quarter, while employment and hours data suggest the October print will be followed up by very strong growth in November. On their own, these data point to growth well above 6% for the quarter. That estimate must be cut back to account for the devastating impact of the November BC floods and landslides, which crippled the interior of the province and continue to disrupt transportation to and from the Port of Vancouver. Our best estimate at this time is that this disaster reduced annualized growth by about 2% in 2021-Q4 leaving the quarter at about 3.5%. Importantly, we anticipate much of the lost economic activity to be recovered in the early months of 2022, as life begins to return to normal in BC and rebuilding begins. This should push real GDP growth to the 5% range in the first half of 2022, roughly closing the output gap along the time frame suggested by the BoC. However, our outlook includes a small negative impact from omicron this quarter and next. Of course, a stronger print for 2021-Q4 GDP than we currently predict could easily suggest an earlier closing of the output gap, and this is not out of the question as the service side of the economy appears to be rebounding sharply.

In addition to the output growth dimension, there is rising evidence that wage growth is accelerating, and it is clear that firms are planning for historically high price increases over the next twelve months. The job vacancy rate is at its highest recorded level. Business unit labour costs are rising rapidly. The impact of input prices and supplier delivery delays seems larger than we earlier assessed. The CFIB’s business barometer suggests that firms expect prices to rise 4.3% in the next year, a pace that is nearly 2.5 times more rapid than the average expectation over history. So even if growth underperforms relative to our forecast, inflationary pressures are rising. As a result, we have raised our inflation forecast for the next two years, with core inflation, defined as the average of the BoC’s three preferred inflation measures, averaging 3% in 2022 and falling slightly to 2.7% in 2023.

With incoming inflation data higher than expected, and our upward revision to future inflation, the real policy rate in Canada has been falling. The BoC is actually more stimulative now than it was a few months ago. Add to this a sizeable depreciation of the Canadian dollar, and monetary conditions are even more accommodative. This is clearly not what is needed.

All this points to an earlier rise in policy rates than we had been carrying. We are moving up our first predicted rate increase in Canada to April but keeping the total rise in rates to 100 bps in 2022. We are also sticking to an additional boost of 100 bps in 2023. Our anticipation at this time is that the BoC will raise rates by 25 bps at each meeting between April and September, then pause in October and December to assess the impacts before resuming rate hikes in 2023. The rate path is unlikely to be linear. It may well be that the policy rate is adjusted in 50 bps increments in some meetings and that other meetings are skipped, but for the moment we assume a gradual hiking path.

We consider a pre-April 2022 move unlikely, but not impossible. It is clear that uncertainty about the health and economic impacts of omicron will continue until well into the new year. Though evidence at this stage appears somewhat comforting in that the virus seems less harmful than the Delta variant, its high transmissibility is likely to lead to a surge in cases during the holiday season with a potential strengthening of public health measures early next year. In any case, it is far too early to have a good read on its impacts. It could also exacerbate supply challenges and raise inflation further. Moreover, given Governor Macklem’s clarity on the link between the closure of the output gap and the launch of the tightening cycle, we think he would need more data than what would be available to him in January and March to be able to justify a rate increase then, unless he were to jettison the tight link to the output gap that he has communicated. Finally, there is a Monetary Policy Report in April, allowing them to fully lay out their views and assumptions, including possible revisions to potential output and the output gap, which would facilitate communicating their decision. History has shown that the BoC has not felt compelled to time key decisions to the publication of the Monetary Policy Report but, given all the elements in play, we think it may this time.

Though we have kept the total increase to 100 bps in 2022, there is a clear upside to this. We will reassess our rate call early in the year when there is more clarity on the implications of omicron, a better sense of year-end growth dynamics, and labour market outcomes. What seems apparent, however, is that the earlier the BoC moves in the year, the more urgency there is, and the more rates are likely to rise in 2022. For instance, it is nearly inconceivable to us that the BoC wouldn’t hike well over four times if they were to move as soon as January as some are forecasting.

In addition to the considerations above, we are increasingly concerned that the BoC’s mandate may change. With roughly three weeks left before the decision deadline, the Government, and possibly the BoC, may be considering serious changes to the BoC’s inflation-control mandate. Why else would they wait until the last minute to announce the results of the 5-year review? As much as we do not think the mandate should change—a view that is strengthened by recent inflation and labour market developments—we have to acknowledge that the odds of a change increase with each passing day. By implication, this means the odds of a change in the BoC’s reaction function are also rising. This inevitably clouds the outlook for inflation and monetary policy in Canada. Will the BoC be more tolerant of inflation overshoots? Will it formally give more weight to labour market information in its decision process? If so, could that force the BoC to, perhaps perversely, pursue a more aggressive withdrawal of stimulus given current conditions in the labour market? The potential impacts of a change seem underappreciated by analysts, perhaps because they expect no changes to the mandate.

Similar considerations are at play in the United States. Growth remains very robust, and inflation is much higher than it is in Canada, though much of that is accounted for by the inclusion of used auto prices in US inflation measures. Our models have for a few quarters now suggested that interest rates in the US should rise in early 2022. Until recently, Fed communications suggested this was completely unrealistic, so we held back our path for the Fed Funds target rate and had forecast a first hike in late 2022. We now expect the Fed to raise rates in June followed by three more rate hikes next year for a year-end target rate of 1.25%.

In relation to the dual mandate, it appears clear that inflation concerns now dominate the Fed’s thinking. Rightly so, in our view. Employment remains well below pre-pandemic levels, with Canadian job growth far exceeding that in the US. At first blush, it may appear that Canadian labour markets are significantly tighter than they are in the US. Key to this assessment is the labour force participation rate, which now exceeds pre-pandemic levels in Canada but remains well below pre-pandemic levels in the US. In principle, this should mean that millions of US workers are ready to re-engage in the labour market, but it seems clear that workers are far less willing to come back to the labour market in the US than in Canada. As a result, it may well be that the US is much closer to full-employment levels than would be implied by looking at recent labour market outcomes relative to pre-pandemic readings. If the US labour force participation rate continues its very slow grind up, it could be that both elements of the Fed’s dual mandate are signalling the same thing: interest rates need to rise.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.