Next Week's Risk Dashboard

- The Fed, the ECB and the separation principle

- Tracking financial market functioning

- What the FOMC might do

- Canadian CPI expected to be firm

- An assessment of BoC cut risk

- BoE: one final hike?

- SNB to follow the ECB

- Will Norges Bank deliver on hike guidance?

- Chinese banks likely to leave prime rates unchanged

- Brazil to hold for a sixth occasion

- Philippines expected to downshift rate hikes

- CBCT may pause

- Turkey’s central bank likely to hold

- A heavy week for Canadian provincial budgets

- PMIs: EZ, US, UK, Australia, Japan

- CPI: UK, Japan, Malaysia,

- Other macro

Chart of the Week

One could well argue that there is strong reason for calm conditions to return to financial markets as regulators work in concert with major players in the financial system to stabilize conditions following a highly tumultuous week. Certainly the magnitude of the efforts and the speed with which they have been applied has been impressive even if several of them introduce longer-run moral hazard problems and adverse incentives. Full deposit guarantees at strained US banks, a new Federal Reserve facility to help against deposit flight and forced liquidation of impaired securities portfolios, improved margin requirements when borrowing from the Fed’s discount window, liquidity supports to US banks and Credit Suisse, big banks helping smaller banks with funding pressures, more cautious forward guidance from the ECB, and late Friday’s news of possible merger discussions between UBS and Credit Suisse have been among the responses.

This week will test this narrative. Judging by how markets ended the week it apparently has not been enough. It is a narrative rooted in rationality in an at-times very irrational world. As a case in point, I recall dismissive remarks that were being made about how the reaction to developments into the Global Financial Crisis were overblown and the policy response was so excessive that it was sure to cause massive inflation. It did. About a decade and a half later! The conditions leading into the GFC were poorly understood and the informational barriers were very high. The forces would prove to be disinflationary and trying to read them with backward looking data was doomed to fail. Today’s circumstances are very different with a better capitalized banking system, more experiences in crisis management and sounder US household finances among the considerations. It is not, however, time to let down our guards; withdrawing the central bank security blanket and tightening liquidity was always, always feared to expose skeletons on the beach in including problems at institutions with weaker funding franchises. But the playbook around anticipating, evaluating and responding to the reverberating effects is fraught with uncertainty.

There are no models for this. It’s far too complicated a world for them to handle. This is entirely a confidence game now and regulators cannot afford to misstep. Increased caution toward the outlook has merit as recession indicators intensify. And yet the confluence of high inflation alongside potential instability is a highly challenging backdrop for the Federal Reserve’s pending policy decisions this week as the main event alongside further developments in financial markets and global banking. Markets want more from regulators and central banks and the cover chart to this week’s edition is one illustration of this point. Acting quickly and decisively out of the gates into a fresh trading week will go a long way toward determining success or failure.

FOMC—HIKE WITH GREATER CAUTION

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee will deliver fresh policy decisions on Wednesday at 2pmET. The statement will be accompanied by updated forecasts and a fresh dot plot showing committee members’ expectations for the fed funds target rate. Chair Powell will be on the hot seat for a full press conference starting at 2:30pmET. No matter what Powell and Co. deliver they will be sharply criticized in what amounts to an extremely difficult balancing act between countering inflation risk, managing financial stability and recognizing that some damage needs to be done to the economy in order to curtail inflation but without tipping things to far.

I don’t envy him. In one sense we might not be in quite the same mess had the Fed not totally misread earlier inflation risk and enabled imprudent behavioural responses. In another sense, however, multiple other players in the system are letting him and the overall economy down with behaviour that is shockingly unacceptable at best. Blaming it on the Fed is extreme. A lot of unwise actions were papered over by rates that were too low for too long and by excessive bond buying that flooded the system with cash, but bad actors have driven idiosyncratic and firm-specific risks that risk deepening macroeconomic challenges.

Markets are nervously pricing around 60% odds of a 25bps rate hike this time and then expect the FOMC to call it quits. I still like the case for hiking at a more measured 25bps pace than believed until very recently, but it may be premature to signal a hard stop. Delivering even a 25bps hike has to be accompanied by further measures to stem a brewing crisis.

The case for further tightening is of course all about inflation and economic resilience to date and whether the shocks to some measures of tightened financial conditions are enough of a substitute for further policy tightening. There is some uncertain rate equivalence to tightened financial conditions, but the key uncertainty is whether it amounts to enough to justify the removal of about 1¼ percentage points of policy rate tightening that had been priced until just over a week ago. In my opinion, while it’s foolhardy to dismiss the concerns, this magnitude of reaction feels overdone if regulators can act quickly. If I’m right, then a vastly different inflation problem than at the start of the pandemic and into the GFC may be worsened should the Fed allow the rates complex to price in such an easier stance.

While the ECB recently hiked by 50bps and shifted to a higher degree of data dependence on the forward bias, the Fed is probably unlikely to go as hard this week. For one thing, the Fed is already in restrictive territory. The ECB wasn't. This gives the Fed more room to maneuver at the margin and to be more careful and circumspect toward developments. For another, the Fed prefers to avoid game day surprises on the policy rate decision. If they have a problem with market pricing that is judged to be either too high or too low, then they would likely find some way of signalling that in blackout which could mean a return to last summer when they delivered a message to markets through clandestine channels via the media.

A key determining factor of whether to continue policy tightening—let alone reinforce market pricing for rate cuts in future meetings—in the face of persistent inflationary pressures is whether market functioning has become impaired to such an extent alongside systemic risk considerations as to freeze the system and pose much sharper downside risks to growth. If so, then central banks could ease up because of the disinflationary consequences.

This is a risk, but I don’t see enough evidence that it has materialized to this point across a blended array of indicators. It might if care isn’t taken so this is a tentative observation. It’s worth reviewing a number of measures in a series of charts.

1. Interbank counterparty risks are proxied by the spread between the three-month forward rate agreement and the overnight index swap rate which serves as a proxy for the risk premium banks demand to lend between each other over a comparatively risk-free rate. Chart 1 shows that this spread has sharply widened with developments over the past week. It is not yet at the wides from earlier in the pandemic, let alone the start of the pandemic. Still, it has remained wider even as supportive measures have been rolled out which serves as caution to the Fed.

2. Chart 2 shows one measure of cross-asset liquidity risk through FX, rates and equities and how it has recently ticked higher but is well below crisis points.

3. The Fed’s preferred measure of how the yield curve views recession risk has deteriorated to its worst levels since 2019 when there were already concerns about the economy even before the pandemic and toward where this measure stood during the GFC (chart 3, grey bars are recessions). It has widened by about 80bps so far this month as markets have gone from soft/no landing optimism toward hard landing fears. The superiority of this measure as a recession predictor over, say, the popular 2s10s spread measure is explained here. It’s saying that the market believes that a recession is a fait accompli. It is a guide provided by a measure that can be highly volatile.

4. Bid-ask spreads: The wider the bid-ask spread the more illiquid markets have become amid uncertainty around market conditions. Chart 4 shows that bid-ask spreads around trading in US 10-year Treasuries had widened toward levels that were close to the early stages of the pandemic, but they have quickly tightened again in the wake of policy measures and after a multi-year period of remarkable stability when buckets of liquidity were being thrown at markets. Corporate investment grade bid-ask spreads (chart 5) and high yield bid-ask spreads (chart 6) have performed similarly.

5. Various credit spreads offer a similar conclusion. Chart 7 shows a rough proxy for US corporate bond spreads over US Treasuries and how they have widened as cyclical risk have risen but are well shy of the wides recorded during the early part of the pandemic, let alone the GFC. To label this as a severe credit crunch would be extreme.

6. Broad measures of bond market liquidity have deteriorated including chart 8 that attempts to measure liquidity across rates, credit and FX markets, but this measure was much worse during past crisis points.

7. VIX—a measure of equity market volatility—is higher than it was during earlier periods but a far cry from prior peaks (chart 9).

8. Having said that, the problems at US regional banks persist as indicated by extreme relative undervaluation to larger diversified banks on the S&P500 (chart 10).

9. Reserves in the US banking system have fallen as the Federal Reserve has embarked upon its policy of tightening (chart 11).

Apart from financial market functioning is the added issue of whether the banking system faces a durable and large increase in systemic risk that could be sharply disinflationary if so. Here too I don’t think we have the evidence to conclude as much, but caution is warranted. Measures that have been rolled out by regulators are material and signal rapid action to smother systemic risk. US regulators’ recent actions are taken some time to work their way through and as explained here. As a side note, while guaranteeing all deposits poses longer run problems, the outcome should be to prevent the mass and sustained migration of deposits from weaker players toward stronger players that happened in the GFC (chart 12) especially given the willingness of stronger banks to inject funding into the more strained banks.

Overall, there is a solid case for the Fed to hike 25bps without the same pressure to match the ECB’s 50bps move and to continue to signal further rate hikes toward a lower terminal rate than it might have had in mind until recently. Maybe it sticks to the December dot plot’s 5 ¼% terminal rate or adds a bit but without going toward the 5.75–6% mark. The so-called separation principle that banking and financial market pressures can be ringfenced with one set of tools while the principle policy rate tool continues to counter ongoing inflationary pressures probably has considerable merit in both the US and Europe.

It’s also possible that this meeting reveals further discussion around the level of optimal reserves in the system. At US$3 trillion – and down from the peak of $4 ¼ trillion – perhaps the Fed is getting its market signals that much lower than that would be shaky ground on which to venture. If so, then perhaps the Fed needs to be open to curtailing the pace of quantitative tightening and hence slowing the pace at which bond sales back into the market are draining reserves and tightening liquidity.

OTHER CENTRAL BANKS—MISERY LOVES COMPANY

The Fed won’t be the only central bank on the hot seat this week, but it will clearly be the dominant one. Brief expectations for others are offered below.

Bank of England—They Were Already Almost Done

Markets are fifty-fifty in terms of the odds of a quarter point hike on Thursday and pricing the central bank to hold thereafter. Wednesday’s CPI inflation report for February and the same day’s Fed decisions and their effects on markets may incrementally inform the risks. Still, like the Fed, the BoE is already further into restrictive territory than the ECB was before its 50bps hike. The BoE was also preparing the way for being close to finished with its tightening campaign and recent events may push it there this week. Governor Bailey has a little more room to be careful in balancing the MPC’s assessments of risks to stability and inflation than President Lagarde may have had.

Swiss National Bank—You Broke It, You Fix it

Most economists expect the SNB to deliver another 50bps hike on Thursday and to therefore follow the ECB. The SNB’s policy rate sits at 1% going into the meeting which positions the central bank as a relative laggard in global policy tightening. Providing liquidity to Credit Suisse helped to temporarily calm markets but further developments and possible policy action ahead of the meeting will likely make it a game time decision on the policy rate. In fact, the CS challenges in the credit default swaps market has already spilled into other banks such as Deutsche Bank CDS pricing.

Norges—Things Have Changed!

In its last policy decisions on January 19th, Norges Bank bluntly stated that the deposit rate will most likely have to be raised again in March. March is here and the decision arrives on Thursday, but a lot has changed since then. For one thing, Brent crude has dropped from nearly US$86 earlier this month toward under $73 now. Global market turmoil and challenges to the global banking system also present fresh risks. Still, underlying inflation picked up to 0.7% m/m in February. Most economists think that Norges will deliver a possible final rate hike this week. Fresh forecasts including revised explicit forward rate guidance will inform this expectation. Recall that the last time explicit policy rate projections were provided they showed significant policy easing over 2024–25 (chart 13). That may be further amplified this time.

PBoC—No Change

China will announce its 1- and 5-year Loan Prime Rates into Monday. No changes are expected to the 3.65% and 4.3% rates. The PBoC recently cut its required reserve ratio by a further 25bps in order to free up more capital for lending purposes in light of downside risks to the outlook. Amid Fed uncertainty, however, the risks to yuan stability likely continue to restrain PBoC flexibility after it left its 1-year Medium-Term Lending Facility Rate unchanged and with that the flexibility of banks to cut their prime rates.

Banco Central do Brasil—A Sixth Hold

The BCB will likely leave its Selic rate on hold at 13.75% again on Wednesday. That would be a sixth consecutive hold. The real has been slightly weakening since early February and before recent turmoil while inflation remains high amid uncertainty toward how the Federal Reserve may act on the same day.

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas—Downshifting

The central bank of the Philippines is expected to deliver another 25bps hike on Thursday after the Fed. Consensus is unanimous. That would be a slower pace of increase than previously. Inflation is running at 8.6% y/y but the overnight borrowing rate has been increased by 400bps over the past year and the peso has been appreciating since November which may give the central bank reason to be more cautious on forward guidance and in light of global market turmoil.

CBCT—Pause?

Taiwan’s central bank was expected to consider holding its policy rate unchanged at 1.75% even before recent turmoil across global markets and banking. Thursday’s decision may face an even stronger case for doing so. Inflation is much better behaved than in other parts of the world after February CPI decelerated to 2.4% y/y with core at 2.6%.

Turkey—Holding Steady

The one-week repo rate is expected to remain unchanged at 8.5% on Thursday. Prior easing in response to a devastating earthquake was accompanied by guidance that it was enough.

CANADIAN CPI—AND WOULD THE BoC CUT?

Canada updates CPI for the month of February on Tuesday and hence one day before the fireworks begin with a round of global central bank decisions.

I’ve estimated a gain of 0.8% m/m in seasonally unadjusted terms as per sampling convention. That translates into a seasonally adjusted rise of 0.5% m/m. Traditional core CPI is guesstimated to have risen by 0.3% m/m in SA terms.

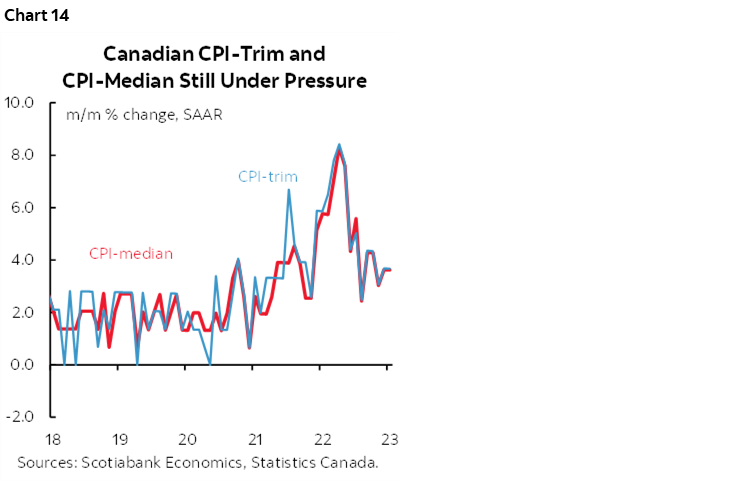

Among the drivers is the fact that February is normally a significant up-month for seasonal pricing pressures in Canada. Gas prices were a minimal influence last month. Food price inflation may moderate after a large gain in January while significant gains in core services inflation and select goods categories such as new seasonal clothing lines could lift the rate of inflation. What happens to the BoC’s preferred measures of core inflation will be key given their stickiness at rates well above the 2% headline target (chart 14).

The BoC will then deliver its ‘summary of deliberations’ from the March 8th decision to leave the overnight rate unchanged at 4.5% while walking a fine line between guiding a conditional policy hold. Unfortunately, new information that arrived literally starting the very next day has probably made much of whatever they have to say in the follow-up communications of relatively little value. A tighter interval between the policy decisions and the publication of the deliberations would be helpful and hence more in the direction of the same-day publication of minutes by the Bank of England and further away from the FOMC’s three-week interval.

Regardless, the issue at hand is whether the Bank of Canada may cut which is what markets are pricing will occur fairly soon. OIS pricing is assigning about a one-in-four chance of a BoC cut in April and almost higher odds of a rate cut in June.

If the BoC is leaning this way, then the April MPR would perhaps lay some of the foundation for this thinking. The distance between now and the April 12th decisions and then the further distance between then and the June meeting counsel extreme caution.

But is there a case to be made for leaning this way at this point? A framework of understanding of the principal catalysts to possible easing may be helpful. The conclusion is to take profits on what has been priced thus far conditional upon avoidance of a full blown crisis.

1. When former Governor Poloz cut in January 2015 and then skipped and came back with another cut at the March meeting it was packaged as a response to a negative terms of trade shock. Such a shock to a commodity-producing and exporting country was marked by about a $50 correction in the Western Canada Select measure of oil prices down to $30 from late 2014 into early 2015. The fear was that this was an imported negative shock to Canadian incomes that would trickle down throughout the economy in disinflationary fashion. It’s premature to judge that this has happened again. WCS oil has fallen from US$65 in early March to about $50 now and had peaked at over $100 earlier in 2022. Today’s correction is material but still offers reasonably attractive oil prices amid uncertainty toward how OPEC+ may respond and the outlook for demand from China.

2. Evidence of impaired market functioning could also prompt a policy response. It’s not clear that the policy rate would be the prima facie way of doing so, however, versus measures to support market functioning such as funding operations. At present, financial markets continue to function reasonably well. In addition to the measures cited earlier in this publication, charts 15–18 provide Canadian evidence. Canadian corporate spreads are performing similarly to US corporate spreads (chart 15). Canada Housing Trust spreads have widened but are still reasonable (chart 16). Canadian credit card trust spreads over the BoC’s overnight rate have markedly tightened (chart 17). Provincial bond spreads have widened but remain far tighter than crisis levels (chart 18).

3. A credit crisis would also motivate easing but here too we don’t have enough durable evidence.

4. Canada’s banking system is sound by virtually every measure including measures of capital adequacy and liquidity plus deposits held at the Bank of Canada (chart 19).

5. The BoC’s policy rate is less restrictive than the Federal Reserve’s relative to what we think are neutral rate estimates for both countries. The BoC’s negative policy rate differential is already vulnerable to currency weakening should the Fed plow on with somewhat further tightening. Cutting in the absence of policy easing at the Fed along the same timeline as markets are pricing for the BoC would risk destabilizing the C$ north of 1.40 USDCAD. A sense that the BoC is embarking upon a meaningful easing cycle could cause a pile-on into the front-end.

6. Canada would be heaping rate cuts onto very tight housing supply, surging immigration stimulus. As it is, the Canadian government’s 5-year bond yield has dropped by about 75bps since month toward the low points of the period since lift-off. Canada is going into the traditional Spring housing market and rate cuts risk inflaming renewed housing imbalances.

7. Last, for now, is the consideration that after having totally misread inflation risk over 2020–21, Governor Macklem may find it more prudent to be careful not to prematurely ease monetary policy.

CANADIAN PROVINCIAL BUDGETS—CLEARING THE DECKS

Seriously? Six out of ten Canadian provinces will release budgets this week including the two biggest ones. They are clearing the decks ahead of the Federal budget on March 28th. I’ve asked Laura Gu to share her thoughts verbatim in what follows below and especially in light of the fact that Ontario and Quebec are among the biggest sub-sovereign debt issuers in the world with relatively high degrees of control over revenue and expenditure policies compared to elsewhere.

Ontario will release its budget on Thursday where we expect some limited revenue upside from this year’s handoff against increased spending in key sectors. Hence, barring new big-ticket policy announcements, the fiscal path will likely remain largely in line with previous updates. Recall that the province’s fall update projects deficits of -$12.9 bn (-1.2% of nominal GDP) in FY23, -$8.1 bn (-0.7%) in FY24, and -$0.7 bn (-0.1%) in FY25 (chart 20). The province’s Third Quarter Finances slashed FY23 deficit by half to -$6.5 bn (-0.7% of GDP)—attributable to significantly higher tax revenues (+$8.7 bn) particularly from corporate taxes—while total expense was raised slightly due to ongoing land claim negotiations. The revision should benefit the province’s bottom line for the upcoming fiscal years, while a weaker growth outlook and prudent fiscal planning could potentially erode some revenue upside. The real and nominal GDP assumptions underpinning the current outlook are both a hair below Scotiabank’s latest forecasts, but the risks are tilted to the downside as heightened uncertainty could lead the real policy rate to go higher and for potentially longer than expected.

Eliminating deficits should remain one of the priorities, but we don’t expect the consolidation path to be as tight as the one outlined in a recent FAO report, in which it projects a budget surplus of $1.0 bn in FY24 based on much lower near-term spending. Some big-ticket policy announcements could be expected with the need to invest in critical sectors such as health and education to support the province’s growing population, but likely will be restrained given mounting headwinds on the revenue outlook. Overall, we believe increased spending pressure and prudent fiscal planning will keep the province in the mild deficit territory for the coming fiscal years, keeping the debt-to-GDP ratio largely in line with FY23’s level (projected at 38.3% in Third Quarter Finances) in the near term.

Set to drop on Tuesday, we expect Quebec’s Budget 2023 to be built on conservative forecasting assumptions and consequently deeper projected shortfalls in the near term. Recall that the mid-year update released in December ramped up near-term spending by incorporating electoral promises and new policy initiatives ($5.5 bn in FY23), offsetting most revenue upside, and the deficit is still on track to end the year at -$5.2 bn (-0.9% of nominal GDP) with two-thirds of the fiscal year wrapped (after payment into the Generations Fund). Since the bulk of fiscal stimulus is non-recurring, planned expenditure is expected to see only slight increases in the near term, narrowing the projected deficit to -$2.3 bn (-0.4% of GDP) in FY24 and -$2.7 bn (-0.4%) in FY25 (chart 21). The province’s mid-year update assumes GDP to grow at 0.7% in real terms and 2.8% in nominal terms in 2023. Budget 2023 could see some downside in the province’s own-source revenue with the government’s prudent practice of conservative forecasting. Government messaging suggests that the income tax cut of one percentage point on the first two tax brackets as a part of the campaign promises will also be incorporated, further weighing on the province’s bottom line. The $2 bn cost associated with the tax measure could come from reduced payments to the Generations Fund.

Beyond FY25, the mid-year update expects longer-term structural shortfall to persist at around $3 bn (-0.5% of GDP), and the government still aims at returning to a balanced budget by FY28 without major spending cuts or tax increases. The book value of the Generations Fund is expected to reach $37.7 bn by FY27. The province is looking to modernize its fiscal anchor in the upcoming Budget 2023 to focus on debt reduction in the next 10-15 years.

Four other provinces will also be releasing their respective 2023 Budget next week—NB on Tuesday, SK on Wednesday, NS and NL on Thursday. As we highlighted in a fiscal roundup report, all four provinces found themselves on stronger fiscal footings as of the latest updates, with NB, SK and NL on track to wrap up FY23 in sizable surpluses (chart 22). We should see revenue windfalls to unwind in FY24 and could expect some deterioration in fiscal balances despite a strong handoff from FY23, with heightened uncertainty around the outlook.

STALE GLOBAL INDICATORS

If that’s not enough for folks, then there will also be some normally hot global economic indicators to consider. The problem this time around, however, is that the soft survey data and the harder data all precedes recent developments in markets and may be totally ignored.

Purchasing managers’ indices top the list toward the end of the week after the Fed is out of the way. Australia and Japan kick it off on Thursday (eastern time) and this will be followed by the Eurozone, UK and US measures on Friday. It’s possible that the results may be treated as stale given the magnitude of recent developments. In more stable times these measures can serve the purpose of informing current quarter GDP growth.

US indicators will fade in the background to the Fed but there will be a few housing and investment gems in the line-up. Existing home sales for February (Tuesday) and new home sales for the same month (Thursday) as pending home sales and model home foot traffic have been rising. Durable goods orders might stabilize after the large 4.5% m/m drop in January that was driven by weaker airplane orders but watch core orders ex-defence and air.

Canada updates retail sales for January and provides guidance for February on Friday. Statcan had already guided that January was a solid month and I’ve pencilled in a gain of 0.7% m/m. February guidance will matter more.

CPI updates will arrive from the UK (Wednesday, see BoE section above), Japan (Thursday), Malaysia (Friday) and with Mexico’s mid-month reading due on Thursday.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.