- Since March of this year, Canadian CPI inflation has accelerated sharply, launching a debate on the sources and persistence of the rise. The persistence of the current surge in inflation will be of critical importance to the Bank of Canada over the next quarters as it assesses its policy stance.

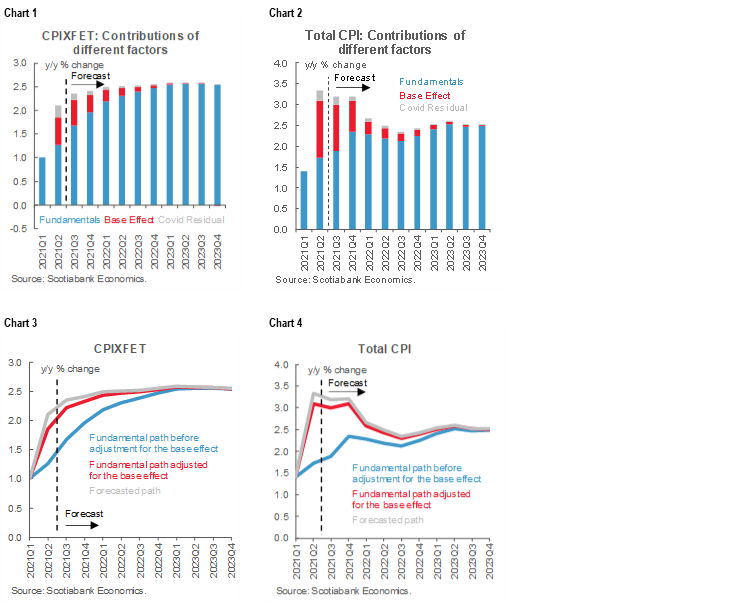

- To inform the temporary vs. persistence debate about Canadian inflation, we decompose recent and forecasted inflation into 3 components: fundamental inflation as determined in a Phillips curve context, which is very persistent; a base effect capturing the year-ago weakness in inflation, which is temporary by nature; and the inflation related to supply chain dislocations due to COVID-19.

- Our analysis shows that fundamental inflation is on a gradual and persistent rising path throughout the 2021–2023 period. Fundamental inflation will reach the inflation target at the end of 2021 and will settle around 2.5% in 2022/2023 because of the emergence of an excess demand.

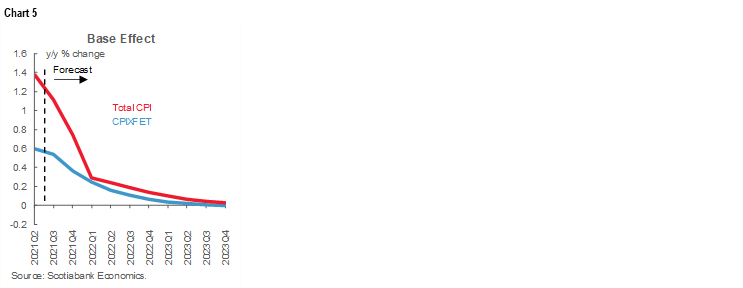

- Temporary base effects, reflecting abnormally low inflation a year ago, explains 71% of the recent acceleration in total inflation and 54% of the change in core inflation. Most of the impact of the base effect is expected to gradually dissipate by the beginning of 2022.

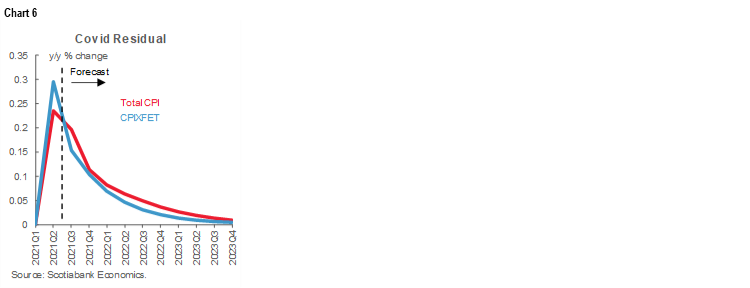

- The remaining inflationary pressure is assumed to be related to supply chain dislocations due to COVID-19. According to our results this factor explains a rise of 0.25 percentage points of inflation, which represents 13% and 23% of the recent acceleration of total and core inflation, respectively. The persistence of this effect is highly uncertain.

To compute the contributions of various factors, we use our inflation forecasting framework, and calculate the impact of the base effects separately. We attribute what cannot be explained by our inflation forecasting framework and base effects to supply chain constraints and other factors.

1. OUR INFLATION FORECASTING FRAMEWORK

We use an Augmented Phillips Curve to forecast core inflation (CPI excluding food, energy and taxes, CPIXFET). This Augmented Phillips Curve includes:

- Forward-looking inflation expectations,

- lag of inflation (i.e. nominal rigidities),

- demand-pull variables like the output gap,

- cost-push variables like the unit labour cost, and

- relative prices (e.g. the real price of oil).

Total CPI is forecasted by an equation that is based on the forecast of the core inflation and the real price of oil. More details on our inflation forecasting framework can be found in the June 24th Inflation Report: Core Inflation at the Bank of Canada: Should We Get Back to Basics? This Inflation Report confirmed that our Augmented Phillips Curve framework is very good at explain and forecasting inflation, especially since 2017.

Charts 1 and 2 decompose the forecast of core inflation (CPIXFET) and total CPI into 3 components: the fundamental level before adjustment for base effects (Blue bars), the base effects (Red bars), and a residual that we associate with the supply constraints or bottlenecks related to COVID-19 (Grey bars). Charts 3 and 4 show the forecasted path of inflation (Grey line), of inflation tied to economic fundamentals adjusted for the base effect (Red line) and of inflation linked to economic fundamentals. The next 3 sections analyze the 3 components of the inflation forecast.

2. COMPONENT #1: THE PERSISTENT FUNDAMENTAL PATH OF INFLATION

The fundamental level before adjustment for the base effect is the path for inflation that would prevail without judgment added to the Phillips curve linked to either the base effect or supply-chain disruptions. Therefore, it is the pure forecast of the Augmented Phillips Curve. It is interesting to note that even before we allow for either the base effect or the supply-chain constraints, the Phillips curve suggests a gradual and persistent rising path of core and total CPI throughout the 2021–2023 period. This trajectory is explained by:

- the rapid elimination of the current excess supply of the economy and the emergence of a persistent excess demand starting in 2022Q1, and

- the recent and forecasted rise of the price of oil.

Consequently, once the temporary base and supply chain effects fade, both core and total inflation will converge persistently to 2.5% in 2022–2023. This level is higher than the BoC’s inflation target because of the excess demand that we expect will prevail at that time. The convergence to the 2% inflation target happens beyond 2023 once the economy gradually goes back to potential.

3. COMPONENT #2: THE TEMPORARY BASE EFFECT AND THE FUNDAMENTAL PATH OF INFLATION ADJUSTED FOR THE BASE EFFECT

In 2021Q2, y/y headline CPI inflation was running significantly above the Bank of Canada’s inflation target, having accelerated from 1.4% in 2021Q1 to 3.3% in 2021Q2. This acceleration in the first half of 2021 can be explained by a number of factors, most importantly the very low inflation rate seen a year ago in the midst of the pandemic, the so-called base effect.1

The mechanics of the base effect calculations can be demonstrated by examining the dynamics of y/y headline inflation in February and March of this year:

- In March, headline CPI was 2.2% higher compared to the same month of 2020, a markedly faster inflation rate compared to the 1.1% inflation seen in February.

- Given that March 2020 saw a nsa m/m decline in the overall price level of about 0.6%, which is a full 1 percentage point below the average pre-pandemic rate of monthly inflation change seen in the month of March since 1995, the price level in March 2020 was about 1% below normal.

- Thus, in March 2021 y/y inflation accelerated by 1.1 percentage points mainly due to the base effect.

The calculation above can be used to compute the contribution of the base effect to the change in y/y headline and core inflation each month starting in March of this year. Once averaged over the quarter, the base effects are seen to contribute +1.4 percentage points to the change in total y/y CPI inflation and +0.6 percentage points to core CPI in 2021Q2 (see chart 5). Beyond 2021Q2, the base effects should help reduce headline y/y inflation as the strong price increases in the summer of 2020 boost the base of comparison. Beyond 2021Q3, base effects should help slow y/y inflation.

4. COMPONENT #3: THE TEMPORARY AND UNCERTAIN COVID-RELATED RESIDUAL

Not everything can be explained by the base effects however, as recent inflation prints are running above the level consistent with the fundamentals adjusted for the base effect. This positive “residual” of about 0.25 percentage points (see chart 6) is likely related to a factor that is not included in the Augmented Phillips Curve framework. In the midst of COVID-19 there is substantial evidence of production and transportation bottlenecks related to the pandemic. This additional inflation pressure likely shows up in the 0.25 percentage point residual component of inflation. We assume that this pandemic-related residual will propagate in the future consistently with the typical persistence of inflation shocks, which is the function of the rigidities and expectation channels included in the Augmented Phillips Curve. According to the Phillips curve, this pandemic-related residual will gradually start to fade quickly in the second half of 2021 and will disappear in 2022. There is a risk that this will persist longer if the pandemic worsens and if governments react by imposing new restrictions. Having said that, the effect on inflation would be offset by the negative effect of the shutdowns on the aggregate demand through the output gap channel of the Augmented Phillips Curve.

5. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR CANADIAN MONETARY POLICY

A large share of the recent rise of Canadian inflation is explained by temporary factors such as the base effect and the COVID-related bottlenecks in the production processes of many sectors. Underneath this strong increase of inflation, the forecasted path of economics fundamentals is expected to push inflation up. If the temporary factors affecting inflation fade as we expect, inflation will settle slightly above the inflation target because of the strong ongoing and expected economic recovery. This dynamic underlies our view that the Bank of Canada will begin raising interest rates in the second half of 2022. If, on the other hand, the impact of supply chain stresses remains, inflation will be notably higher and possibly require a significantly more aggressive monetary tightening.

1 See here for further discussion of the base effect calculation.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.