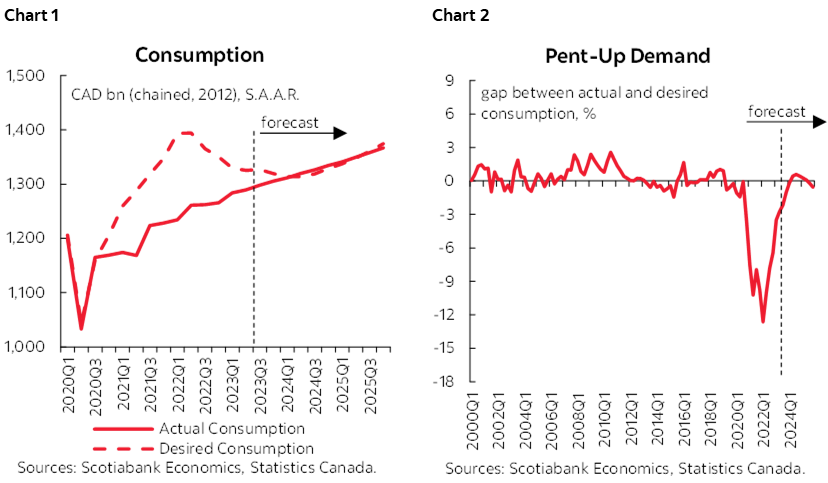

- Since 2020Q2, actual consumption has been below desired. The gap between the two—a measure of pent-up demand—explains in large part the incredible resilience of the Canadian economy to the rapid rise in interest rates.

- Low and accommodative real interest rates, record low unemployment, combined with increased net wealth through rising home equity and excess savings and high oil prices drove a substantial increase in Canadians’ desired level of consumption. As these factors began normalizing and reversing, desired consumption has subsequently declined, with most of the adjustment so far attributable to monetary tightening and restrictive real rates.

- Supply bottlenecks have on the other hand limited Canadians’ ability to increase their actual consumption to fulfill their desired level. As supply bottlenecks resolve, actual consumption increases and the gap between actual and desired consumption narrows.

- The Bank of Canada needs to eliminate this pent-up demand in order to move the economy into excess supply and alleviate inflationary pressures. We expect this to occur in 2024Q2, at which point the BoC will be able to gradually reduce its policy rate.

The Canadian economy has been incredibly resilient in the face of rapidly rising interest rates. Much of this surprising strength can be ascribed to pent-up demand—a measure of the gap between actual and desired consumption—amongst a broad range of things, including increased wealth and population growth. While all three factors are linked, this note focuses on pent-up demand as a source of economic resilience. We investigate the drivers of desired and actual consumption, how they have evolved over time and throughout the forecast horizon, and the net impact on pent-up demand. Desired consumption is our measure of households’ optimal level of consumption which we estimate based on different economic fundamentals like income, interest rates, and wealth (see appendix for full list).

During the pandemic, the gap between actual and desired consumption grew larger (charts 1 and 2). Low and accommodative interest rates, easy access to credit, strong labour market recovery and record low unemployment, combined with increased net wealth through rising home equity and excess savings and high oil prices, drove a substantial increase in Canadians’ desired level of consumption. On the other hand, supply constraints and public health rules hampered their ability to increase their actual consumption to fulfill the desired level.

Despite the BoC’s efforts to slow the economy to alleviate inflationary pressures by rapidly and aggressively hiking its policy rate, the gap between actual and desired consumption has remained negative (a more negative gap means more pent-up demand). This persistence of pent-up demand explains in large part why the economy has been incredibly resilient in the face of many headwinds including tighter monetary policy. As a result, the real policy rate must remain in restrictive territory until pent-up demand and the upward pressure it creates on the output gap and inflation is alleviated.

Note that our equation for desired consumption does not capture financial wealth, which increased during the pandemic through an accumulation of savings and deposits as governments rolled out fiscal supports with restrictions on spending due to lockdowns. This financial wealth effect might add to the level of desired consumption as some households have a large amount of liquid savings to support their spending in the face of higher rates, leading to potentially higher and more persistent pent-up demand than estimated by our model.

FACTORS BEHIND PENT-UP DEMAND

1. Interest Rates

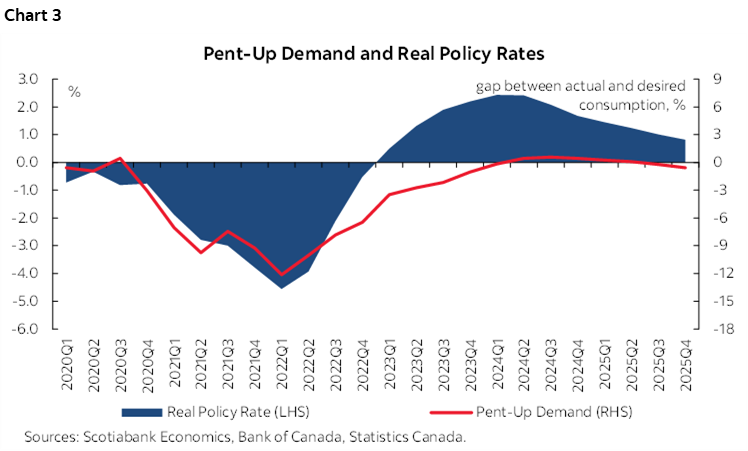

The onset of the pandemic brought with it ultra low real rates as governments and central banks across the globe reacted to support households and financial markets through lockdowns and other pandemic related measures. Such low and accommodative rates naturally increase the level of desired consumption as households have easier access to credit.

Even as the BoC began raising its policy rates at the start of 2022, hiking by a cumulative 400 bps that year alone, the real rate—the one that matters for economic growth, measured as the nominal rate minus the expected inflation rate—remained negative throughout 2022 as inflation roared. The real rate was still in accommodative territory in the first quarter of 2023, only rising above its neutral level of 0.5% in the second quarter of 2023.

Only when real rates began to increase did pent-up demand begin to ease as rising real rates reduced the level of desired consumption (chart 3). In fact, a large proportion of the elimination of pent-up demand so far can be explained by the fall of desired consumption driven by higher real rates. Given the persistence of pent-up demand, however, an episode of persistent positive real rates is needed to entirely eliminate it, considering the lag in the transmission of real rates to desired consumption. As shown in chart 3, we are forecasting real rates to begin declining right around the elimination of pent-up demand in 2024Q2.

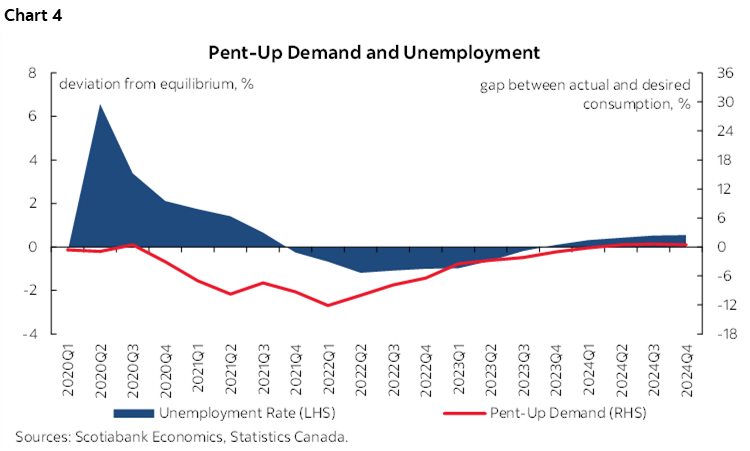

2. Strong Labour Market Recovery

The post-pandemic labour market recovery has been nothing short of incredible. Canada has added almost a million jobs (in seasonally adjusted terms) since the onset of the pandemic, with the unemployment rate reaching record lows. This strength in the labour market and low unemployment has acted as a support for the Canadian economy as households were able to hold on to their jobs and incomes in an environment of uncertainty and rising prices and rates.

The level of desired consumption subsequently increased as more jobs were added to the economy and the unemployment rate moved towards and eventually fell below its equilibrium level—often referred to as the NAIRU, the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment—adding to pent-up demand and of course, inflationary pressures (chart 4). As the gap between the unemployment rate and its equilibrium level began narrowing again, so did the gap between actual and desired consumption.

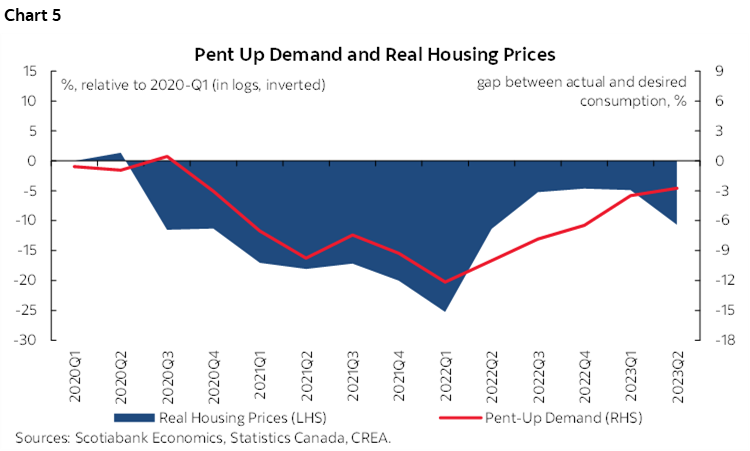

3. Home Prices and Wealth Effect

It is no secret that since the start of the pandemic and up to 2022Q1, home prices in Canada soared, not only in nominal terms but also in real terms (i.e., when adjusted for inflation). With much of Canadian households’ wealth attached to housing, this increase in home prices translated to an increase in net wealth which directly impacted households’ level of desired consumption and in turn pent-up demand, bringing both up (chart 5—note that home prices relative to 2020Q1 are inverted. A negative number means home prices are higher than in 2020Q1). Real housing prices only started to decline relative to the start of the pandemic when the BoC began its hiking cycle in 2022Q1, bringing desired consumption and pent-up demand down with it.

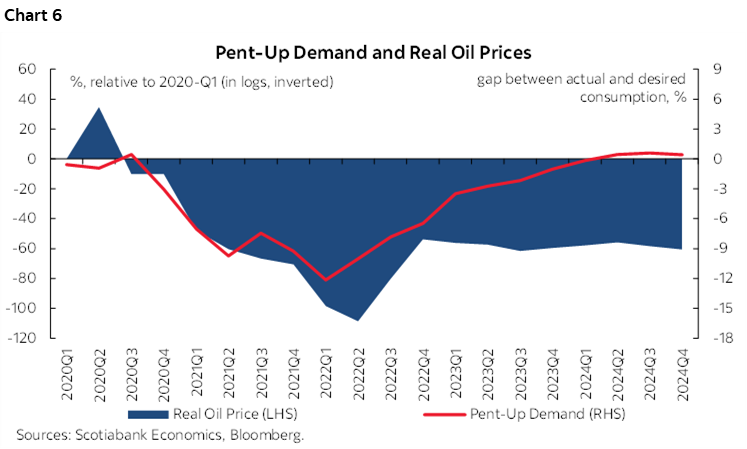

4. Oil Prices and Wealth Effect

A big driver of inflation following the onset of the pandemic had been the surge in oil prices, brought about by supply shortages and significantly exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war that began in February of 2022. This affected the Canadian economy differently than others given its status as one of the world’s largest oil producers and net exporters.

While households had to grapple with higher gas and energy bills, higher oil prices were on net a positive to the Canadian economy as they boosted the terms of trade, creating a positive wealth effect, and supported investment and employment in oil producing provinces. This in turn increased desired consumption and pent-up demand (chart 6—note that oil prices relative to 2020Q1 are inverted. A negative number means oil prices are higher than in 2020Q1). As oil prices began normalizing, desired consumption and the gap with actual consumption narrowed.

THE ROLE OF SUPPLY CONSTRAINTS

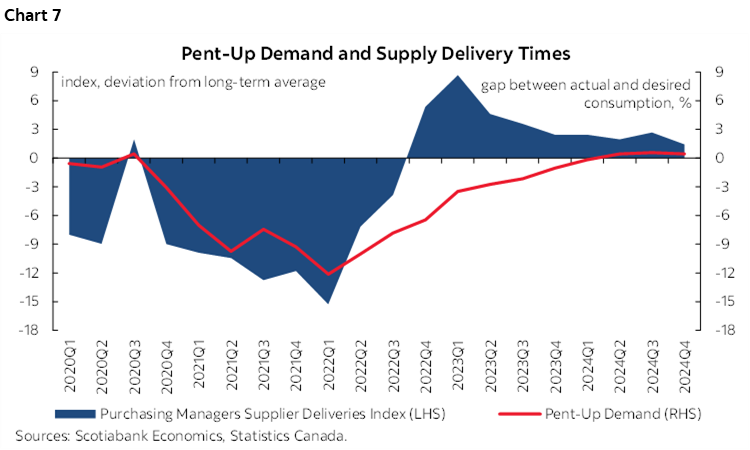

Another prominent feature of the pandemic era has been supply bottlenecks. The pandemic disrupted global supply chains and created shortages across all consumer goods resulting from lockdowns and border closures. This meant that even as Canadians desired to consume more, they were unable to do so as anything from furniture to bikes to cars was unavailable for purchase. This lowered the level of actual consumption while factors discussed above boosted desired, further widening the gap between the two and exacerbating pent-up demand (chart 7—a higher supplier deliveries index means faster delivery times while a lower index means slower delivery times and more supply bottlenecks).

As supply constraints started to improve, pent-up demand started to close as Canadians were able to consume more to fulfill their desired level of consumption.

Given the initial strength of desired consumption and the inability of actual consumption to catch up due to supply constraints, pent-up demand has persisted despite rising rates and other headwinds, explaining in large part the resilience of the economy so far that had forecasts of recessions repeatedly pushed out. Looking ahead, we expect pent-up demand to wind up by early next year, mostly driven by a lowering of desired consumption as actual consumption continues to increase to catch up, albeit, at a slower pace than seen since supply bottlenecks eased.

MONETARY POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The Bank of Canada needs to eliminate pent-up demand, which is at the root of the recent resilience of the Canadian economy, in order to create an episode of excess supply and alleviate inflationary pressures to bring inflation back to its 2% target. We forecast pent-up demand to be eliminated by the second quarter of 2024, largely driven by higher real rates and lower desired consumption as a result. Only then will the BoC be able to start gradually reducing its policy rate without undermining its efforts to tame inflation.

APPENDIX

We estimate the level of current desired consumption based on economic fundamentals like income, interest rates and wealth. We also estimate a dynamic equation to forecast actual consumption which features forward-looking behaviour, with agents attempting to optimally set their consumption to equal the desired path, in the face of adjustment costs and conditional on the expected evolution of many economic drivers.

The drivers of desired consumption (sign of the effect in parenthesis):

- Disposable income (+)

- Real policy rate (-)

- Unemployment Rate (-)

- Real oil price (+)

- Real housing prices (+)

- Potential GDP (+)

- Debt/GDP (to capture fiscal transfers) (+)

The drivers of actual consumption:

- Desired consumption (+)

- Real policy rate (-)

- Disposable income (+)

- Real exchange rate real (-)

- Real oil price (+)

- Stock market (+)

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.