THE BANK OF CANADA CAN NO LONGER AFFORD TO WEIGH GROWTH OR LABOUR MARKET OUTCOMES

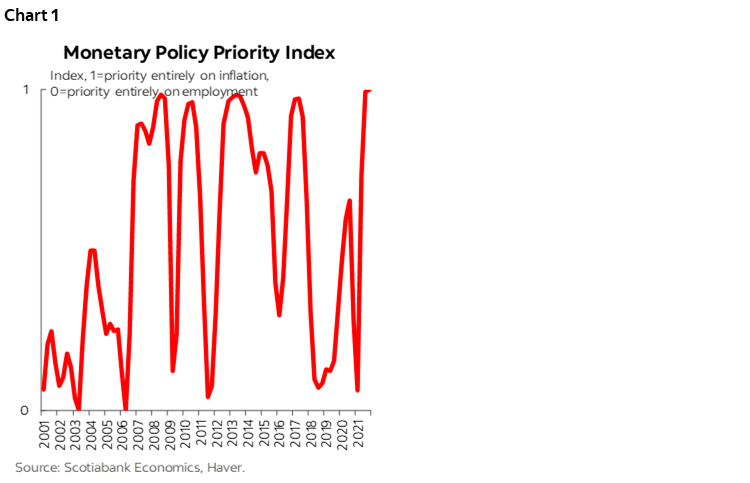

- In light of the Bank of Canada’s revised monetary policy framework that takes more explicit account of labour market developments, we estimate a time-varying monetary policy priority index that measures when and how the Bank has shifted its focus between inflation and the unemployment rate over history. We find that there have been large shifts in priority between inflation and labour market outcomes over history.

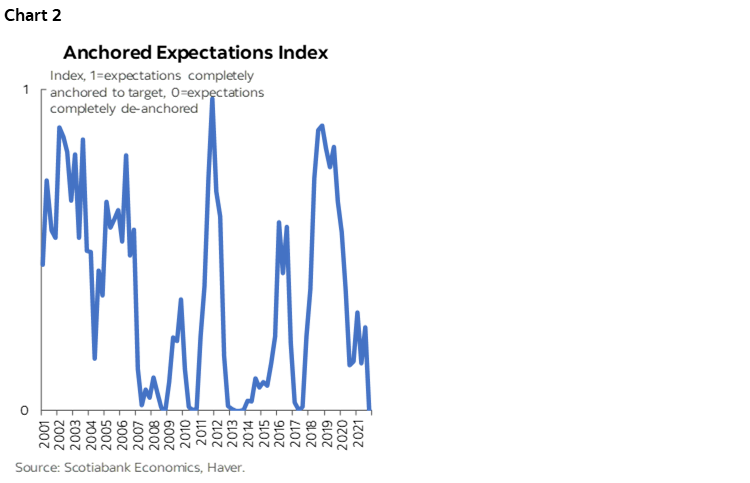

- We also estimate an anchored inflation expectations index to identify when inflation expectations become de-anchored due to persistent deviations of inflation from its target, and how this impacts the Bank’s ability to shift its priorities between inflation and labour outcomes.

- Our findings indicate that as of late 2021, the Bank’s priority should have been squarely on inflation. We also find that inflation expectations have been completely de-anchored from the 2% target since late 2021. This recent de-anchoring of expectations means that the Bank’s monetary policy will need to be more aggressive to bring inflation back to target.

Economies around the world have been experiencing persistent and rising inflation, with rapidly diminishing spare capacities and increasing supply constraints and bottlenecks. This is happening at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions are dominating the global economic outlook.

In Canada, while the labour market fully recovered all its COVID-19 losses, the recovery has been unequal, with employment in high-contact sectors still significantly below pre-pandemic levels. Despite a sharp increase of inflation, the Bank of Canada passed on raising its policy rate in its January meeting and eventually raised its policy rate in March. Throughout the pandemic, as inflationary pressures took hold and proved more persistent, many wondered whether the Bank was prioritizing labour market outcomes over keeping inflation under control. For much of last year, Governor Macklem and his colleagues made it clear that they viewed labour market slack as a factor holding inflation and policy back.

The Bank’s newly announced framework more formally asserts that it will use its flexible inflation targeting regime to actively seek and support maximum sustainable employment when conditions warrant. In this report, we propose the theory that the Bank of Canada has indeed been already following this approach in conducting monetary policy, shifting its focus between inflation and unemployment rate over time and given economic conditions. To test this theory, we estimate a time-varying monetary policy priority index, which varies depending on whether the Bank puts more or less weight on inflation or the unemployment rate gap. This index would complement the Bank’s commitment to report when and how labour market outcomes have factored into its monetary policy decisions as it can tell us where the weight is at any given point in time.

We also consider the role that inflation expectations play in providing the Bank the necessary flexibility in shifting its priority from one indicator to another. The theory here is when inflation expectations are well anchored to the Bank’s target, inflation should react less to demand shocks, giving the Bank more room to shift its focus away from inflation and onto the unemployment rate gap and probing the value of the equilibrium unemployment rate (i.e. NAIRU). Similarly, we test this theory by estimating an anchored inflation expectations index, which varies depending on whether inflation expectations are more anchored to the target or based on inflation’s recent and expected behaviour.

METHODOLOGY

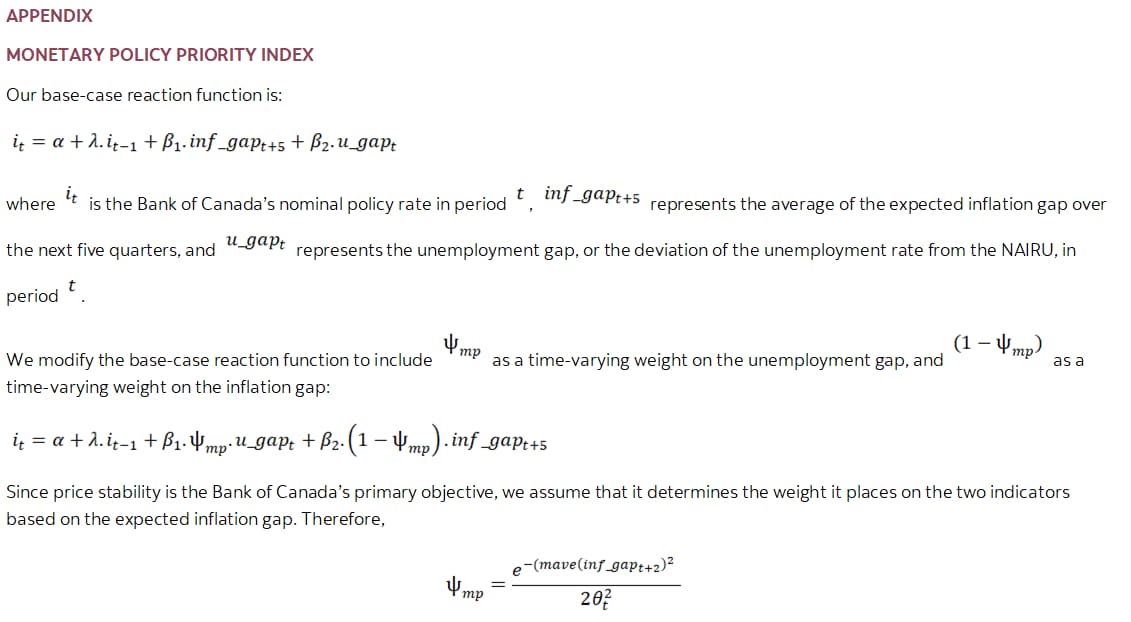

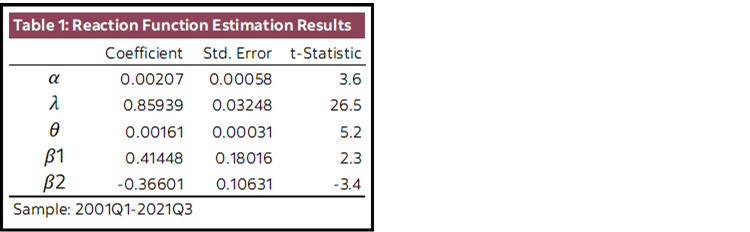

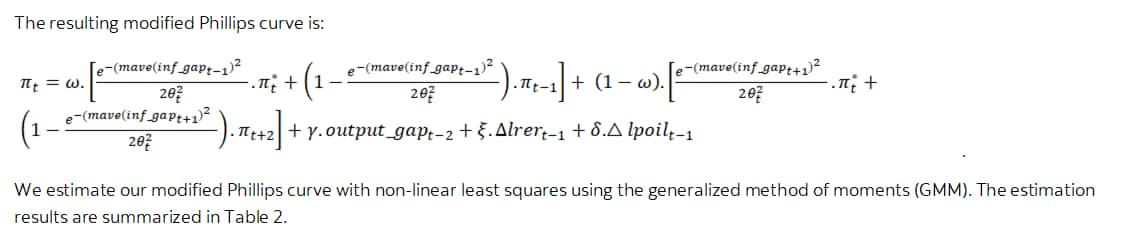

I) MONETARY POLICY PRIORITY INDEX

We estimate a forward-looking reaction function that follows a simple Taylor-type rule, where the Bank can react to both an indicator of economic activity (in this case the unemployment rate gap), and the expected inflation gap. As in Lalonde 2006, we allow the weights on the two respective gaps to vary over time by adding a non-linear, time-varying monetary policy priority index which varies between 0 and 1. Thus, at any given time, the Bank can decide to prioritize either inflation control or probe for the minimum unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation. Since inflation control is the Bank’s primary objective, it determines how to distribute the weight based on the expected inflation gap. The further expected inflation is from target, the more weight will be placed on the inflation gap, and the higher the priority index will be.

We note here two challenges that may hamper our results. First, the complex nature of a non-linear estimation. Second, the overnight rate has been at the effective lower bound for long stretches of time during our estimation period. As such, our dependant variable did not always move in response to inflation and unemployment. This limits the variability that could be captured and explained by the model. Despite these challenges, our results are statistically significant and provide a useful tool to help understand the Bank’s priorities and how it conducts monetary policy.

The priority index depends on a key estimated coefficient, which can be interpreted as the Bank’s bias towards inflation. The smaller this coefficient is, the faster the Bank will reorient its priority from the unemployment rate gap to the inflation gap in response to deviations of inflation expectations from target. In other words, it will take a smaller deviation to shift the Bank’s focus back to the inflation gap—its ultimate objective. The model and key estimated parameters are presented in the appendix.

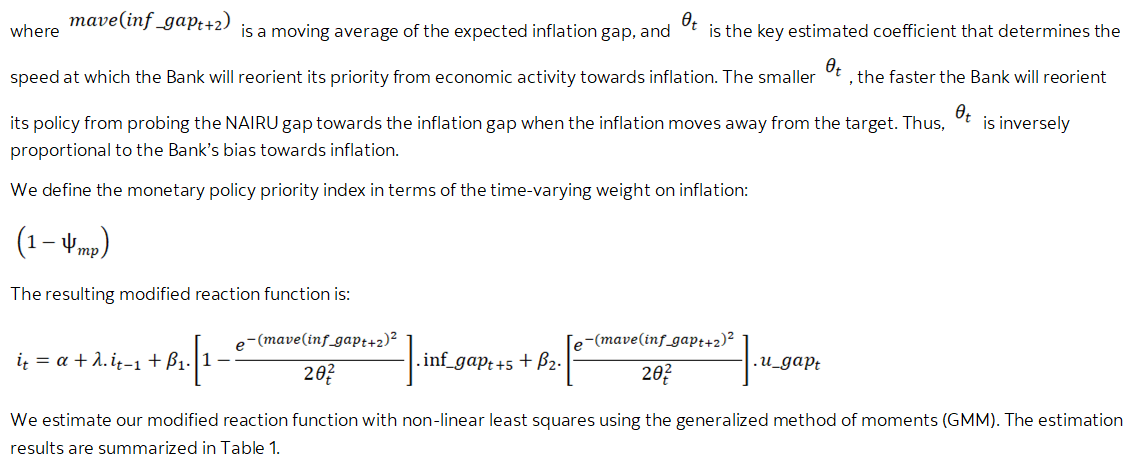

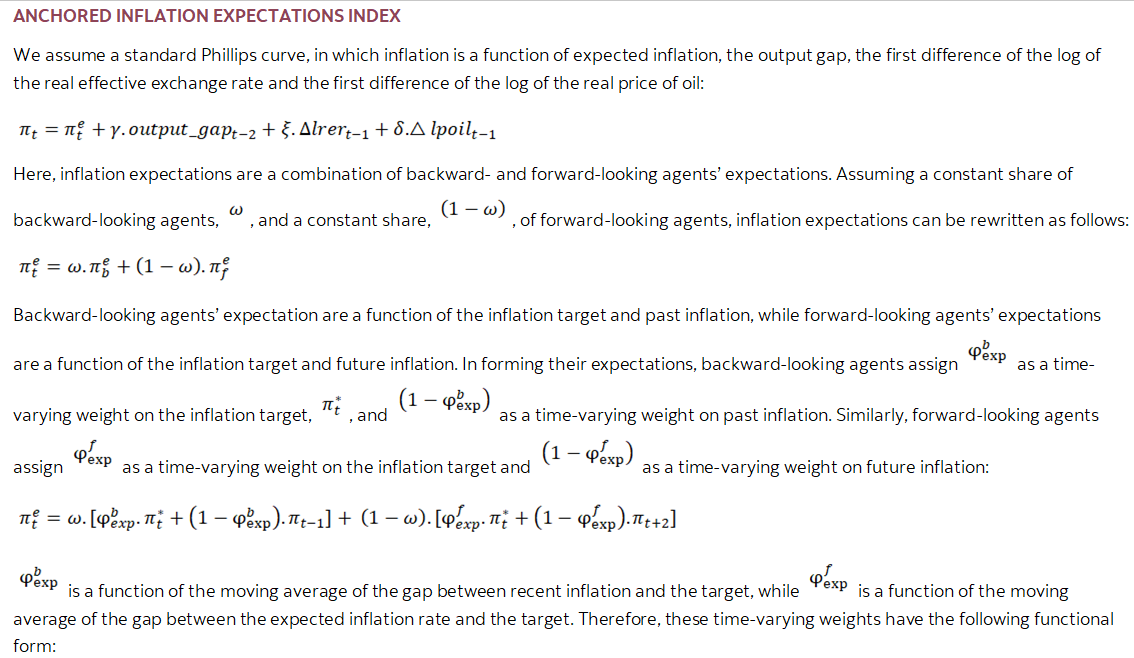

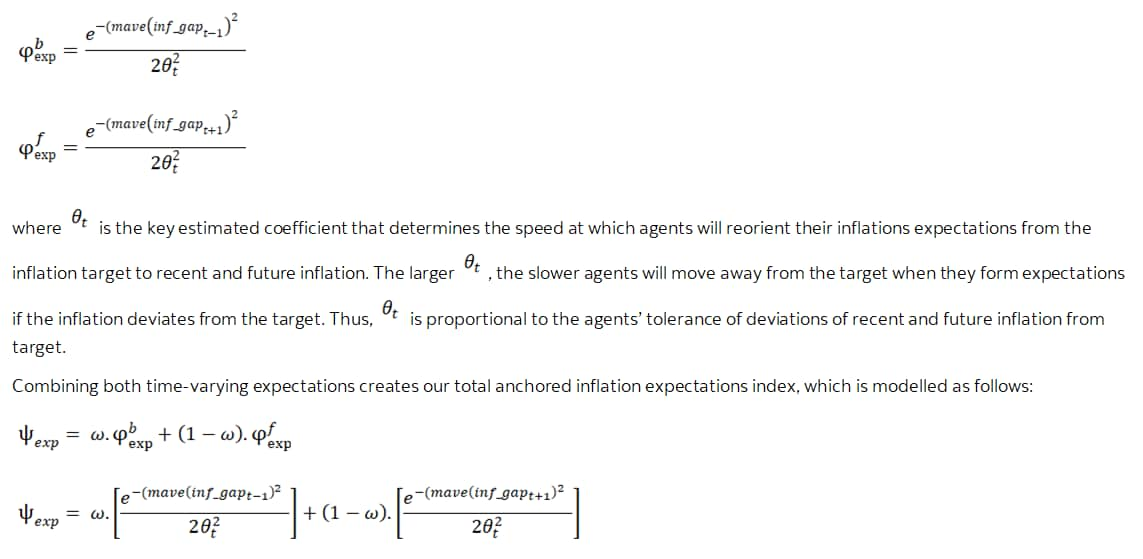

II) ANCHORED INFLATION EXPECTATIONS INDEX

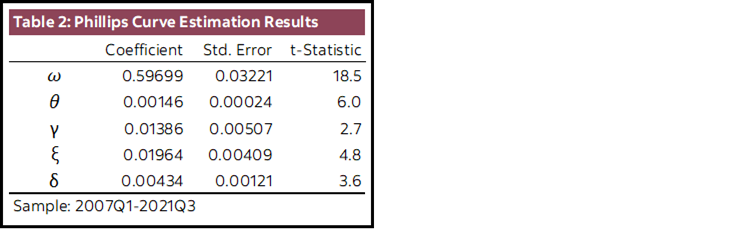

We estimate a Phillips curve in which inflation expectations are a function of the inflation target, past inflation and future inflation. As in Lalonde 2005, we allow the weight on the inflation target to vary by adding a time-varying anchored inflation expectations index which fluctuates between 0 and 1 depending on inflation’s recent and expected behaviour. The closer past and future inflation is to target, the closer the index is to 1 and the higher the probability agents assign to the Bank’s ability to meet its target in the next couple of years. In other words, the more anchored inflation expectations are to target, the higher the index, and the less sensitive inflation is to demand shocks. Note that the index says nothing about the Bank’s long-term credibility and success in bringing inflation to target. This is a time-varying weight on the inflation target in inflation expectations.

Similar to the priority index, the anchored inflation expectations index depends on a key estimated coefficient. The larger this coefficient is, the more agents will tolerate a larger deviation of inflation from the target before de-anchoring the inflation expectation from the target. We noticed that since 2007 this estimated coefficient has increased substantially which means that the Bank’s credibility increased over recent history.

III) RESULTS AND MONETARY POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Chart 1 plots the monetary policy priority index. The behaviour of the priority index indicates that the Bank has indeed been shifting its priority between inflation and unemployment rate over the past two decades, placing more weight on the unemployment rate gap during periods when the expected inflation gap was relatively small which allowed the monetary policy to focus on employment and probe for the value of the equilibrium unemployment rate.

The index briefly shifted to inflation in the first half of 2020 when the pandemic first hit and resulting restrictions slowed demand and put downward pressure on prices and increased the expected inflation gap (in absolute terms). As economic activity and inflation expectations quickly rebounded, the priority index shifted back to unemployment before increasing concerns about inflation being persistently above target pushed the index to 1 in late 2021. According to the priority index and historical standards then, the current expected inflation gap should have had the Bank focused squarely on inflation starting in mid 2021. It has been able to wait to do so because there were other tools at its disposal such as the government bonds purchasing program, which the Bank ended in November of last year, and forward guidance.

Chart 2 plots the anchored inflation expectations index. We see a clear inverse relationship between the two indices—when inflation expectations are well anchored to target, inflation is less sensitive to demand shocks, giving the Bank more room to probe the unemployment rate gap. Inflation expectations were well anchored to target in the two years leading up to the pandemic, and during that time the priority index was also tilted towards the unemployment rate gap. But since the pandemic hit, inflation expectations have been gradually de-anchored, as agents put increasingly more weight on inflation’s behaviour rather than the 2% target. This is not surprising given inflation’s recent behaviour and the Bank’s delay in hiking its policy rate. With the anchored expectations index dropping to 0 in 2021-Q3, the Bank should have acted quickly, shifting its focus back to inflation in order to re-anchor expectations.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.