China’s “dual circulation” strategy, in which internal and external parts of the economy will complement each other, will dominate Chinese economic plans for the next five years and beyond.

We assess that the government’s plan to bolster the Chinese consumer does not signify that China is turning inwards; instead, the strategy helps with China’s ambitions to reach a higher level of economic development and increase the country’s global economic power.

The inevitable emergence of China as the world’s largest economy and a major consumer market will require the rest of the world to adopt an attitude shift and an increased aptitude for multilateral engagement.

The term “dual circulation” is currently receiving increased attention in China and globally. Though a new expression, it will unlikely be a short-lived catchword, as it is set to characterize China’s economic development strategy for years to come. China’s 14th five-year plan for 2021–2025—discussed at the Fifth Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party at the end of October and to be finalized at the next National People’s Congress, mostly likely to be held in March—will largely center on the concept of dual circulation. While official details of the plan remain scant, this report will try to shed some light into the dual circulation concept and assess what it means for the Chinese economy and the rest of the world.

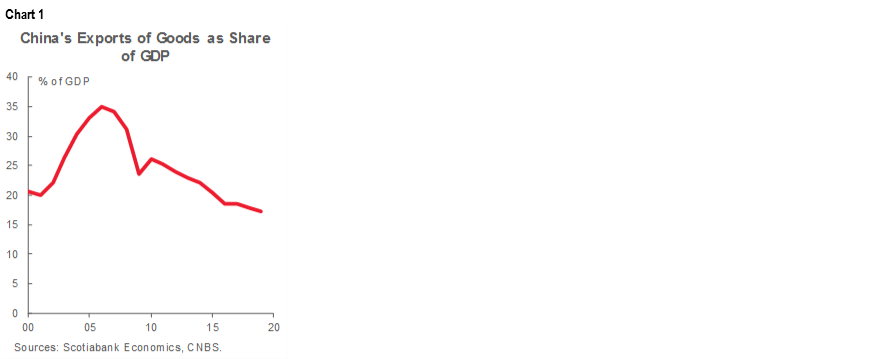

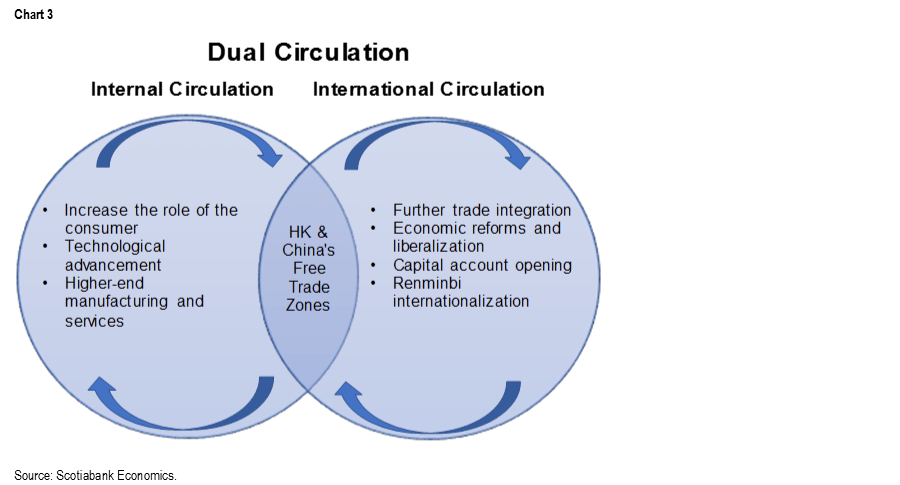

Under the dual circulation strategy, China will increasingly focus on utilizing its large internal market and domestic demand. China’s export-led growth model, which has been a key driver of the economy since the country’s accession to the WTO in 2001 (chart 1), will now officially be replaced by an approach that simultaneously pays attention to both the domestic and external sides of the economy. Indeed, the dual circulation means that the internal and international “circulations” complement each other (chart 3 on next page).

The timing of the new strategy has triggered some concerns regarding rising protectionism in China. We acknowledge that Chinese policymakers’ focus shift toward internal demand dynamics follows escalated tensions between China and the US and a wave of protectionist biases around the world as economies try to cope with the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, we do not think the strategy implies that China is turning inwards. The reality is that the Chinese economy is—and has been for several years already—in the midst of a structural transition toward a more consumer- and services-oriented economy. We consider the dual circulation strategy to be a pragmatic and important element in the country’s quest for reaching a higher level of economic development and per-capita income. In fact, we assess that increasing the role of the consumer in the Chinese economy over the next five years will be critical in order to avoid the “middle-income trap” that threatens many newly-industrialized export-oriented countries. At the same time, we acknowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many weaknesses in global supply chains, and the internal circulation part of the strategy will help improve China’s self-reliance in strategically important industries, such as technology.

INTERNAL CIRCULATION

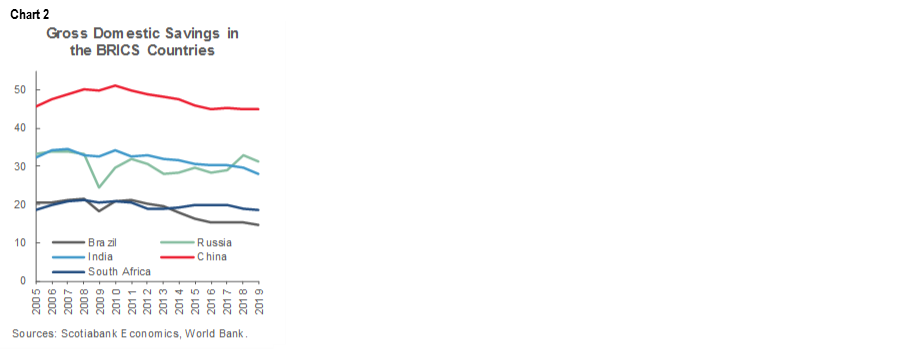

Policies that relate to internal circulation will primarily focus on raising household incomes and the role of the consumer in the economy. Higher wages can be achieved by reforms of the land and residency system that would support urbanization. Improvements to the social safety net would lower China’s relatively high savings rate (chart 2), further supporting consumer spending prospects.

In our assessment, another key element of internal circulation is technological advancement that will be critical to move the country higher in the global value chain. China aspires to be a global technology powerhouse, underpinned by domestic innovation. Moreover, given various other countries’ concerns regarding China’s security and intellectual property practises and resultant restrictions on China’s access to technology resources, the country’s focus on internal technological capabilities, such as domestic production of semiconductors, will provide it with some protection from external tensions. Related to China’s technological aspirations is another core element of internal circulation—the country’s industrial strategy. China aims to strengthen and diversify its industrial supply chains and push for higher-end manufacturing. Simultaneously, the nation aims to further develop the services sector and support services-oriented manufacturing, thereby assisting the economy’s climb to a higher level of development that is more in line with major advanced economies.

INTERNATIONAL CIRCULATION

It seems clear to us that China aims to remain relevant in the global market. In fact, the Chinese leadership has continued to promote further global and regional trade integration and deeper investment ties; we expect such efforts to remain in place in the coming years, forming a key aspect of China’s international circulation. We assess that this approach will help China to increase its global economic might, particularly against the backdrop of the US having turned inwards over recent years. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—the world’s largest free trade agreement, covering 30% of global GDP—is a prime example of how China will be able to increase its influence in regional and global affairs. The RCEP was signed by its 15 members (China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand as well as the 10 Southeast Asian nations forming the ASEAN group) on November 15 and is waiting for ratification by the member nations over the course of 2021.

The implementation of structural reforms is a fundamental part of China’s dual circulation strategy. While reforms will underpin the development of the domestic economy, they will also be imperative from the international circulation viewpoint as they assist with China’s integration into the global economy and financial markets. Indeed, Chinese policymakers have stated their continued commitment to the economy’s further liberalization. In our view, the list of needed reforms is long, yet we assess that the internationalization of the renminbi (RMB), deepening of capital markets, strengthening of financial markets’ regulatory standards, and continued gradual relaxation of the capital account will remain the government’s priorities over the next five years. Further trade and investment integration with the rest of the world along with financial market reforms will help with the internationalization of the RMB. At the same time, to strengthen the renminbi’s global role China’s capital controls need to be relaxed further. We expect Chinese policymakers’ capital account opening measures to primarily focus on portfolio inflows in the foreseeable future (as liberalizing portfolio outflows prematurely poses significant risks to domestic financial stability); therefore, we expect the Chinese renminbi to face a gradual strengthening bias vis-à-vis the US dollar over the coming years, as international investors readjust their portfolios to include a larger share of Chinese assets. Structural changes tend to be interconnected; we consider that reforms centered on the financial markets and regulatory transparency will also help with the development of China’s services industry, one of the government’s priorities.

THE ROAD AHEAD

The dual circulation strategy is intended for China’s long-term development, though we note that it will likely bring about some short-term benefits as well. Policies that fall under the strategy and simultaneously strengthen confidence and boost domestic demand—such as tax and fee cuts for the consumer and the higher-value-added manufacturing sector—will assist with China’s economic recovery. A supportive policy backdrop is important, given that prospects for external demand remain uncertain as several of China’s trading partners continue to struggle with containing COVID-19.

Based on the information currently available about the five-year plan for 2021–2025, the Chinese leadership has not specified a real GDP growth target for China. We assess that China’s output will expand by 5–6% y/y through the next five years following a forecasted COVID-19 -related rebound of over 8% y/y in 2021. While China’s economic growth is expected to decelerate gradually over the foreseeable future, the country will likely continue to outperform the US. Based on our calculations, China is set to surpass the US as the world’s largest economy by the end of the decade. As this change in economic power will be accompanied by China’s structural transition toward a consumer- and services-based economy, China is increasingly positioning itself as a market rather than a source for cheap goods. The change in China’s status will not be without its challenges, however, as large differences in ideology as well as in political and economic structures will remain in place between advanced economies and China. We are of the view that China’s continued economic development is inevitable. Against this context, we highlight that it is essential for advanced economies to engage in multilateral dialogue with China in order to reach consensus on shared rules and standards so that all participants can be better off in the new world order that awaits us.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.