FORECAST UPDATES

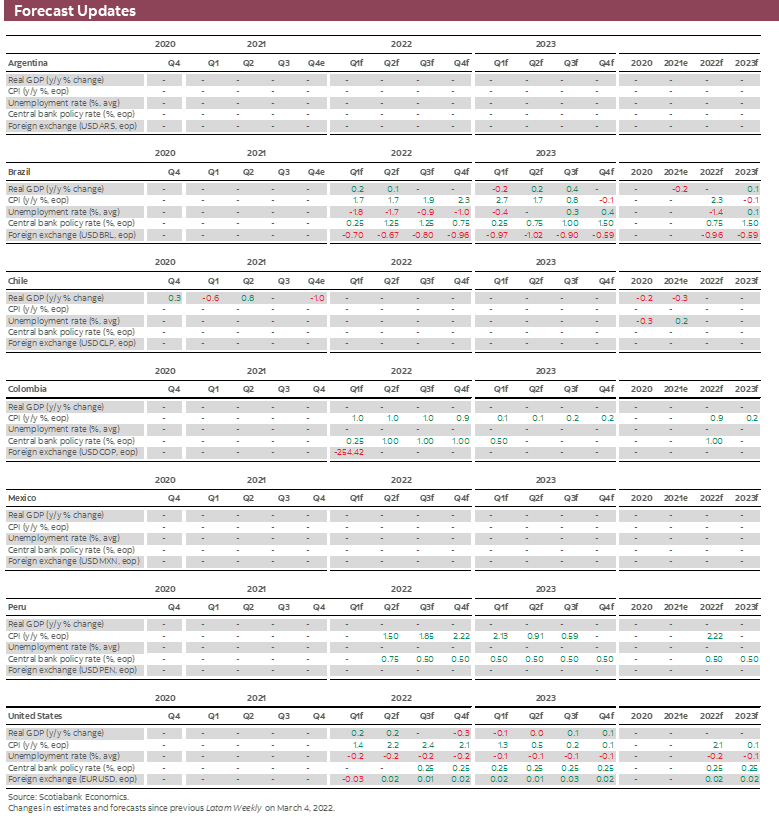

- Higher headline inflation and rising core and expected inflation have led Scotiabank economists in the Latam region to revise their forecasts. See the full set of changes in the forecast tables below. Further revisions are likely in the weeks ahead as geopolitical developments spill over to commodity prices and disrupt global supply chains.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- The short-term economic and financial impacts of the war in Ukraine are coming more clearly into focus. The most immediate impact is on commodity prices, which have spiked in the weeks following the Russian invasion.

- Higher inflation requires Latam central banks to tighten more aggressively in order to return inflation to target. But in an extraordinarily uncertain environment, the higher interest rates that response may entail increase the likelihood of policy overshooting—and recession.

- The longer-term consequences of the conflict on the global economy are more opaque. The sanctions imposed thus far on Russia are likely far more comprehensive than most observers thought possible. Their impact on global supply chains will only be assessed over time.

- Going forward, the longer that hostilities continue, the greater the risk that additional sanctions and other “carrots and sticks” are introduced. In this event, Latam countries, and world writ large, could face a whole new world.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

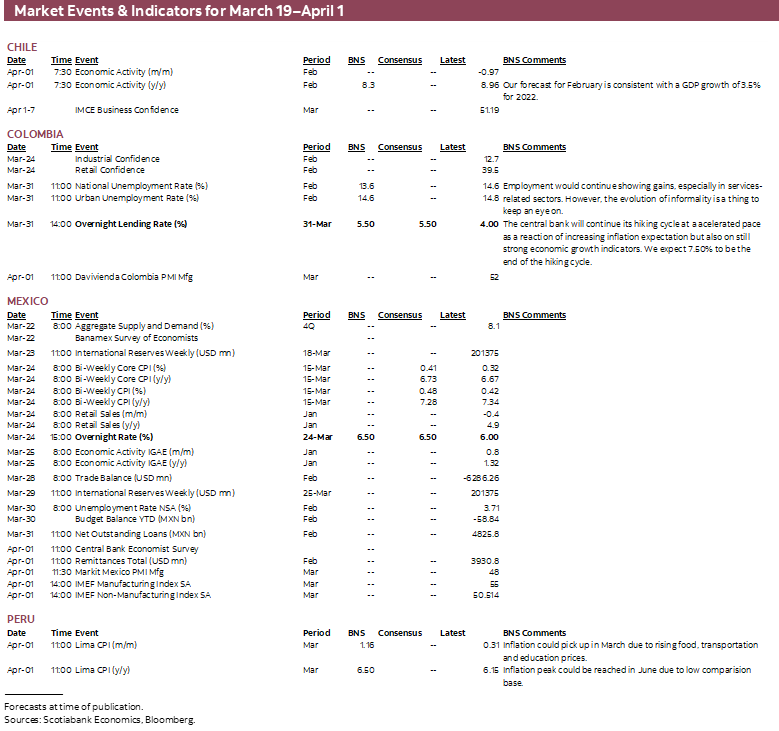

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period March 19–April 1 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: A Whole New World?

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- Higher commodity prices are feeding through to headline inflation and forcing Latam central banks to re-evaluate the projected path of their policy rates.

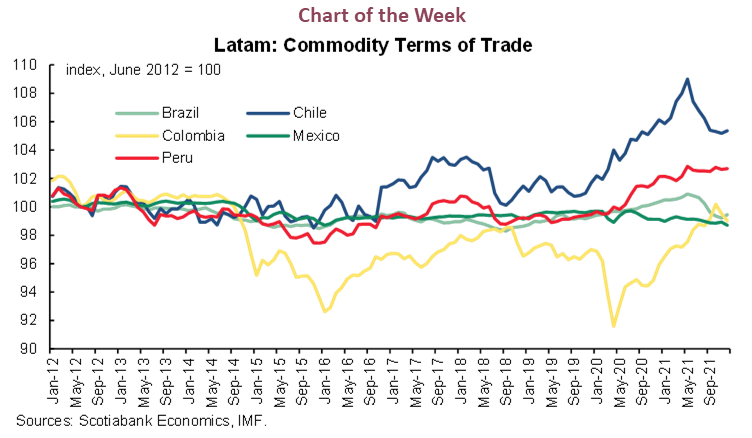

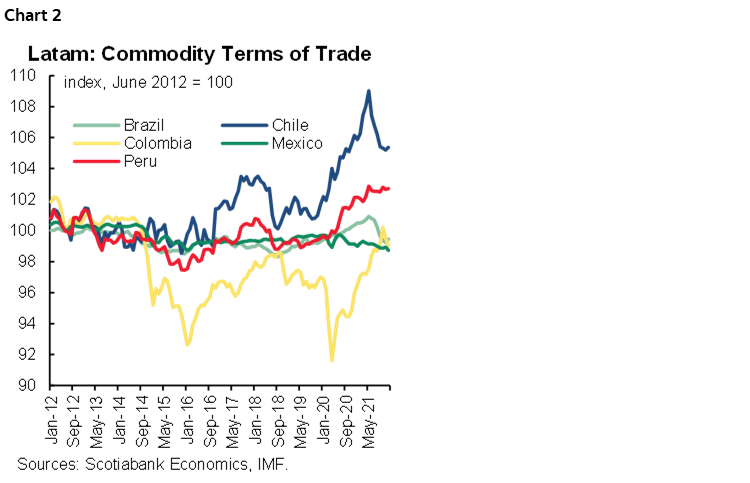

- At the same time, higher commodity prices represent a terms-of-trade shock that will affect real incomes and output. Not all countries in the region will be equally affected, as the pattern of exports and imports vary.

- Moreover, the correlation between changes in commodity price terms-of-trade and output differs across countries. In this respect, it is important to separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to these shocks.

- Arguably, however, most countries in the region have become more exposed to commodity price shocks. This could prove a challenge should Russia’s invasion of Ukraine lead to increased volatility as the process of globalization is halted or reversed. This outcome would, in effect, create a whole new world.

COMMODITY PRICES AND SANCTIONS: SEPARATING THE WHEAT FROM THE OIL

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine enters its fourth week, the devastating toll in terms of human lives and destruction mounts. At the same time, the collateral damage to the global economy continues to increase. Some of this damage is already being observed and its costs measured. Other effects are likely to play out over time, and with much greater uncertainty with respect to their eventual impacts. And while a cessation of hostilities would likely contain the former, the latter could prove much more persistent, affecting global trade and investment long after the fighting stops.

The most immediate impact of Russian aggression has been a spike in commodity prices (chart 1). World prices of commodities from oil to wheat have jumped as markets have priced-in the possible effects of sanctions on Russian oil exports and disruptions to the spring planting of cereal crops in Ukraine. Higher commodity prices, which had been trending up even before the Russian invasion, have fed through to inflation across the Latam region and around the globe. Price moves over the past several weeks will exacerbate those effects.

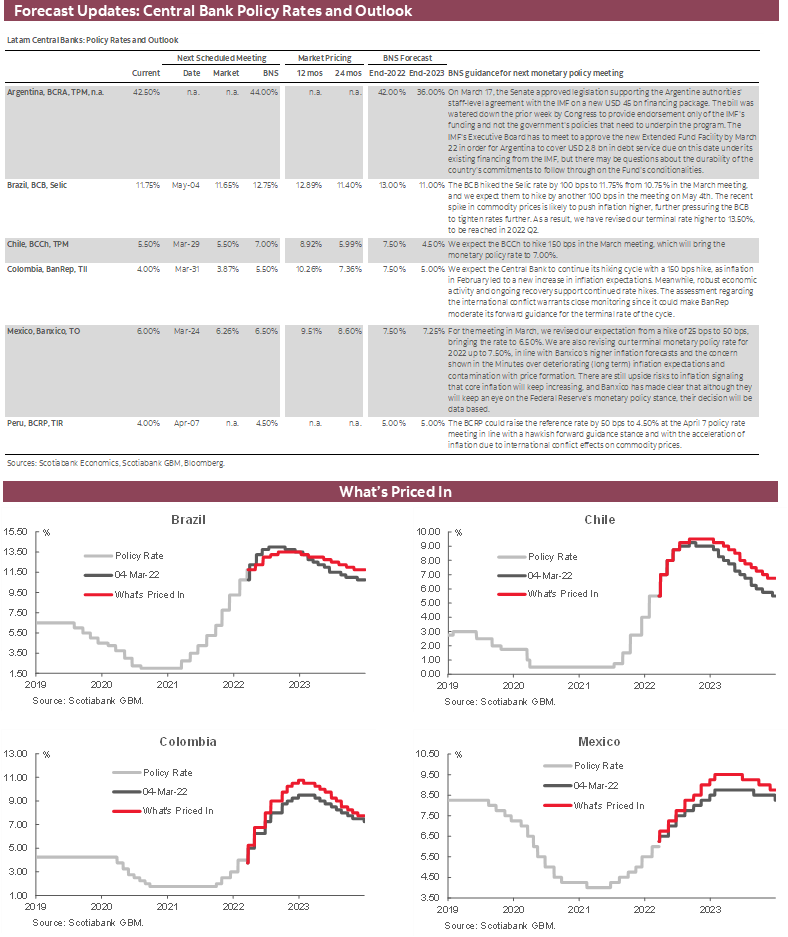

The timing of this commodity price shock could not have been less propitious. Latam central banks, which had proactively embarked on a tightening cycle, raising key policy rates to anchor inflation expectations, now face a far more challenging task of threading the needle between the higher interest rates needed to return inflation to target and the risk of policy overshooting—tightening too aggressively, putting the economy into recession. Prior to the most recent price shocks, prospects were good that central banks would succeed in this task. As their forecasts suggest (see forecast table above), Scotiabank economists around the region continue to think that central banks will successfully preserve price stability, with inflation peaking over the near term before gradually falling to target ranges over the medium term, without engendering a policy-induced recession. But the risk of a miscalculation has undoubtedly increased.

In this environment of heightened uncertainty, the calibration of monetary policy has become even more critical. In Brazil, where the economy seems precariously perched on the edge of stagflation, the BCB hiked its key Selic rate by 100 bps, on March 16, in response to higher inflation that threatens to bleed over into expectations; Scotiabank’s experts now call for the benchmark rate to peak at 13.5% in the second quarter of 2022, up from 12.25%. The BCB is a single-mandate inflation-targeting central bank that focuses exclusively on inflation control. However, that isn’t the case with respect to central banks in the region that have dual mandates (inflation and growth), even if that is defined in terms of “efficiency” of inflation control (i.e., minimizing the output losses needed to ensure price stability). And in calibrating their monetary policy responses, other central banks incorporate inflation and output (output gap) objectives. Nevertheless, as Scotiabank’s team in Bogota discusses below (see Country Updates), assessing the appropriate stance of monetary policy using a reaction function approach likewise leads to the conclusion that the profile of policy rates must be ramped up. To achieve its objectives, BanRep will have to move more aggressively, with two 150 bps hikes in March and April, followed by a further 50 bps in June, to bring the policy rate to 7.50%. In response to the commodity price shock, Scotiabank economists in Lima have also raised their forecast for Peru’s policy rate, which is now expected to peak at 5.0%, up from 4.5%.

Higher commodity prices also have terms-of-trade effects that will impact economic performance going forward. But those commodity price shocks will vary across the Latam region. As the old adage goes, it is important to separate the wheat from the chaff in discerning the impact of commodity prices. While commodity prices were largely quiescent in the wake of the global financial crisis, with minimal variation across Latam counties, large divergences in the region’s terms of trade to emerge in 2015 (chart 2). Colombia’s commodity term of trade deteriorated, for example, probably owing to the decline in oil prices. Chile and Peru subsequently experienced positive terms-of-trade shocks as global metal prices strengthened prior to the pandemic.

Most Latam countries have benefited from higher commodity prices as global activity has recovered over the past 18 months. Mexico is an exception, however, in that its commodity price terms of trade has been relatively stable. As Scotiabank’s team in Mexico City point out in the Country Updates below, this is likely explained by the fact that Mexico is no longer a net exporter of oil. Moreover, they highlight the fiscal tradeoff that is involved in insulating consumers from rising oil prices if the oil price shock lasts sufficiently long. In a sense, the government may have to choose between medium-term fiscal sustainability and allowing higher energy prices to feed through to inflation, which would require a more aggressive response by Banxico. That response would increase the likelihood of a recession.

Peru is another country to watch. Like Chile, it has benefited from higher metal prices, but more recent increases in oil and cereals prices expose it to large import price shocks (see discussion below). Inflationary pressures from imports of key products—oil, wheat, edible oils, corn, and fertilizer—will erode real incomes (chart 3). In this respect, while the direct exposure to the conflict is limited, with Russia and Ukraine accounting for only about two percent of Peru’s total trade, between 20% and 25% of total imports are fuel and other commodities and there is no way to avoid the effects of higher prices. As Scotiabank’s team in Lima put it, smaller trade balances may be a harbinger of things to come. In this regard, Peru underscores the importance of “separating the wheat from the oil”.

Exposure to terms-of-trade shocks emanating from higher commodity prices is one thing, the effects of those shocks on incomes and output are another matter entirely. Here, too, there are important differences across the Latam region. The simplest possible way to access these effects is to look at the correlation between changes in the country-specific commodity price terms-of-trade and changes in GDP (table 1).

These correlations must be interpreted with caution; as the well-known caveat goes, “correlation does not imply causation”. That is, higher growth could put upward pressure on commodity prices rather than vice versa. But while such effects are theoretically possible, given that commodity prices are set in global markets in which the influence of any one country, apart say from the US or China, is small relative to the rest of the world, they are unlikely. In any event, the IMF team that constructed the country-specific commodity price indices tested for such effects and found little evidence that domestic developments drive fluctuations in a country’s commodity terms-of-trade index.

Not only are there large differences across countries, but there are also significant changes in correlations over time. These changes are evident in a comparison of two time periods, 1981–2000 and 2001–2021. Significantly, for most countries, the correlation increased over time, with the sign switching from negative to positive in the case of Colombia and Peru. (Brazil is an anomaly here in that terms-of-trade shocks are negatively correlated with GDP.) Such changes may be explained by a range of factors related to structural changes and economic development—the degree to which production is diversified across different industries, openness to external trade, etc. Whatever the underlying factors driving them, these changes suggest that Latam countries are likely more exposed to terms-of-trade shocks today than they were 20 years ago.

This conclusion could have important implications going forward. Viewed over a 40-year span, commodity price shocks have become both far more numerous and larger (chart 4). In this long-term perspective, the relative stability of the “Great Moderation”, encompassing the 1990s and early 2000s, stands out. That stability began to break down, however, as commodity prices spiked just prior to the global financial crisis in 2008. Arguably, this increase in volatility reflected the speculative excesses that fueled the housing boom spilling over into other markets, including commodities. Whatever the cause, a similar pattern has emerged more recently. And with Latam economies potentially more sensitive to commodity terms-of-trade shocks (positive and negative), policymakers face a more challenging environment.

In this context, it is reasonable to ask what the future has in store for the global economy. The direct impact on global supply chains of the sanctions on Russia already in force will only become clear over time. Unfortunately, the one certainty is more uncertainty. This is because the longer that hostilities continue and sanctions remain, the greater the risk to the global economy from disruptions to supply chains and volatile commodity prices. Moreover, the greater the likelihood that additional sanctions would be introduced. And countries that may wish to continue trading with Russia—for profit or for geopolitical and ideological reasons—could well be subjected to secondary sanctions, further disrupting global production.

At the same time, pressure could be brought to bear if sanctions fail to elicit the desired behaviour with leverage gained through a range of “carrots and sticks”, including tariffs, financing from international financial institutions (the IMF and development banks), as well as access to swap lines with the Fed and other central banks. The deployment of these instruments would halt the process of globalization that has transformed the global economy over the past four decades. For Latam countries, as for all, their use would constitute a whole new world.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Constitution Continues to Advance, One Month after the Closing of the Discussion

Jorge Selaive, Head Economist, Chile

+56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

COVID-19 SITUATION CONTINUES TO IMPROVE

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has slowed in recent days. The test positivity rate fell to 15%. At the same time, occupancy rates of ICU beds and COVID-19-related death rates are increasing at a slower pace. Meanwhile, the vaccination campaign has reached 94% of the eligible population. The rollout of booster (third) doses continues—reaching 13.2 million people—and the new booster dose (fourth) is in progress—with 1.8 million people covered.

INFLATION GETS A BREAK IN FEBRUARY DUE TO SPECIFIC DECREASES IN SOME SERVICES

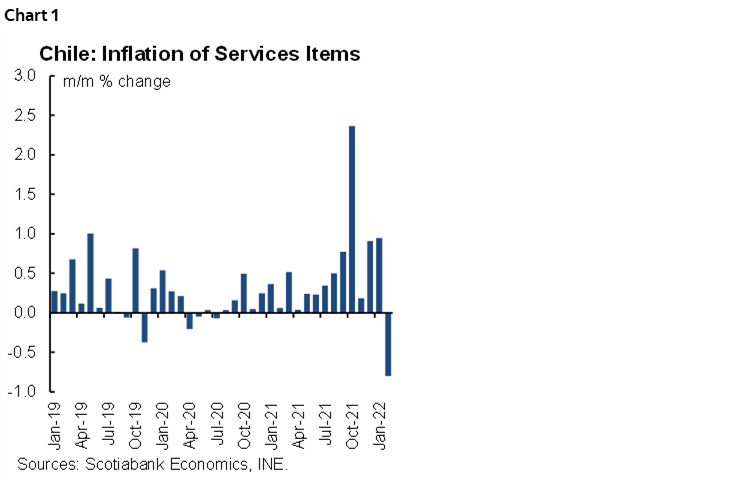

On Tuesday, March 8, the statistical agency INE released the CPI for February, which increased 0.3% m/m (7.8% y/y). Higher food and fuel prices, somewhat offset by declines in goods and services prices resulting from the downward correction of tourist packages and air transport services, explain this result. The drop in services prices was explained in part by the reversal of the unusual price rises observed last October (chart 1). Looking forward, inflation pressures will continue in the short term, but are expected to decrease in the second half of 2022.

Significant price pressures remain, however, with food prices registering a record increase of 1.8% m/m in February. Another item fueling February’s inflation was gasoline, which rose 1.9% m/m and accounted for +0.06 ppts of the total m/m increase. Core inflation remains high, at 0.7% m/m, with a high percentage of products contributing to inflation. Excluding foodstuffs and energy (SAE), inflation was 0.3% m/m (6.6% y/y) in February.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS: DISCUSSIONS BEGIN ON CENTRAL BANK OBJECTIVES

The work of the various thematic commissions established to draft the new constitution moves forward, with voting (both in principle and on an article-by-article basis) continuing. Note, the Justice Systems Commission, which considers—in the second block of norms presented to the plenary—articles about the definition and the objectives of the central bank. At the same time, the Political System Commission is close to presenting its first report to the floor of the Assembly.

In the last two weeks, the Assembly approved 13 articles (of 16 approved in principle) from the Fundamental Rights Commission, as well as seven articles (of a total of nine previously approved) from the Constitutional Principles Commission. These articles will be incorporated in the draft of the new constitution. The Assembly also approved one article (of a total of six approved in principle) from the report by the Environment Commission, which likewise passes to the draft of the new constitution. The Knowledge and Culture Systems Commission presented its second report to the plenary with modifications to the rejected articles, of which seven new norms were approved by the floor of the convention and will move to the draft of the new constitution (table 1).

Each proposal needs a two-thirds majority in the Assembly (103 votes) to be approved. If an initiative is rejected, it goes back to the original commission to be discussed, modified, and put to a vote on the floor of the Assembly in a second round. This process will extend to April 28, at which point the Assembly will have the final draft of a new constitution. After that, a Commission of Harmonization will ensure the consistency and coherence of the approved norms.

FEW DAYS FOR A NEW POLICY MEETING IN THE CENTRAL BANK

In the fortnight ahead, the monetary policy committee of the central bank will meet March 29, at which we expect a further hike in the benchmark rate. On March 30, the CB will release the quarterly Monetary Policy Report updating the macroeconomic scenario. We expect an upward adjustment in its inflation forecast for December 2022 and a new path for the Monetary Policy Rate, consistent with the new scenario. In addition, also on March 30, the statistical agency (INE) will publish the unemployment rate for the three-month period ending in February, followed on March 31 by INE’s release of manufacturing production and retail sales data for February.

Colombia—Persistent Inflation Requires Aggressive Response

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9166 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Economist

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9400 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

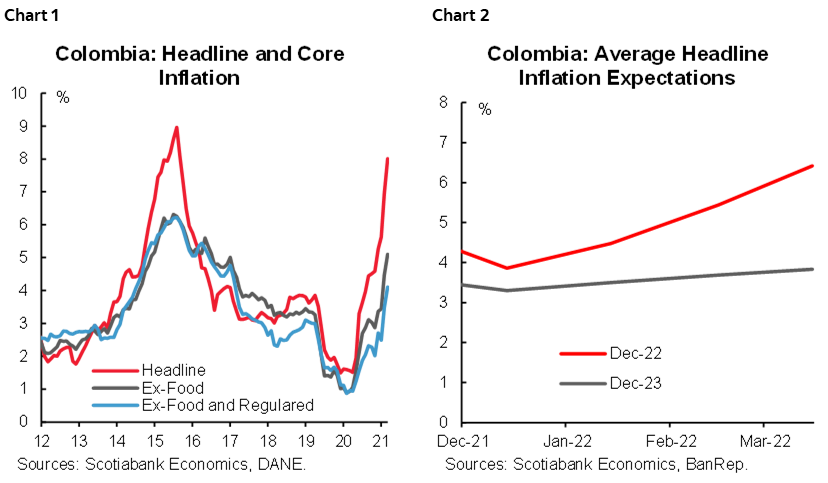

The Colombian economy has started 2022 with steam. In fact, coincident indicators for January showed an economy that continues closing the output gap, while other indicators such as energy demand and tax collection also showed continued strength in Q1-2022. However, there is evidence that companies and households are not as confident. Persistent inflation has raised production costs (higher input prices) and reduced household disposable income, especially for lower income households, since February food inflation was above 23% y/y while lodging and utilities increased 8.86% y/y, both of which are key expenditure items. In addition, headline and core inflation measures have surprised markets and analysts for three consecutive months, with December 2022 inflation expectations at 6.46%, and expectations for December 2023 now at 4%. The central bank (BanRep) probably needs to accelerate its hiking cycle, even if that means shifting to a contractionary policy stance for a short period of time. The question is by how much.

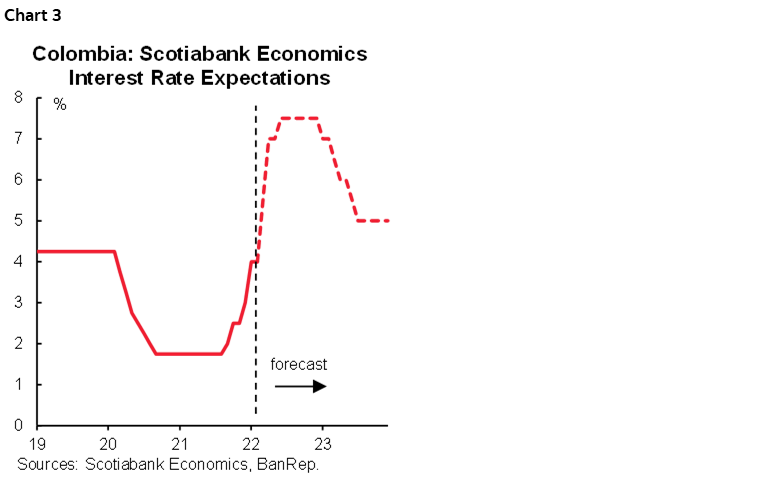

To answer this question, we use the reaction function approach outlined in our Country Update in the February 4 edition of the Latam Weekly. We incorporate recent changes in spot and inflation expectations to calculate the new terminal rate and the path that we think BanRep will follow to get that rate.

Before starting the analysis, it is important to recall that a conventional reaction function incorporates three main components: i) an estimate of the neutral rate, normally in real terms; ii) a projected output gap; and iii) an inflation gap. In our view, the neutral rate and the output gap have not materially changed since our last projection update. The neutral interest rate continues to be 1.9% in real terms, while the output gap is expected at -1.4% in 2022 and -0.4% by 2023, with initial data for Q1-2022 supporting that perspective. Economic activity since the start of the year appears to be resilient, which helps to close the output gap at a faster pace. Therefore, if we were to only consider the long-run policy rate and output gap, we would conclude that BanRep should increase policy rate to 5.75% and maintain that rate for an extended period.

However, the third part of the reaction function, the inflation gap, has changed significantly. Colombia has had two significant upward surprises (January and February) of 44 bps on average, while core inflation (ex-food measure) has increased from 3.44% y/y in December to 5.1% y/y in February. In other words, with this 1.66 ppts increase core inflation is now already above the ceiling of BanRep’s target range (chart 1). Moreover, recent headline and core inflation numbers are becoming embedded in inflation expectations for December 2022 and December 2023, which have increased significantly (chart 2). Currently, analysts think that annual inflation will be 6.46% by December 2022, while expectations for December 2023 remain at the top of the ceiling of BanRep’s target range of 4%.

From the perspective of an orthodox inflation-targeting central bank’s reaction function, recent increases in headline, core, and expected inflation means that BanRep must act faster and perhaps more aggressively. In fact, our model points to two 150 bps hikes in the March and April meetings, followed by a 50 bps hike in June to bring the policy rate to 7.5%. Having said that, the model also indicates that, in a scenario in which inflation peaks at 8.32% by March 2022 and starts to slowly converge to the target, returning to the target range (2–4%) by March of next year, BanRep should start to slowly cut the policy rate starting in January 2023 to achieve a neutral rate of 5.0% by the end next year (chart 3). This profile would keep the real (inflation-adjusted) policy rate close to neutral so as limit the damage to domestic demand.

Mexico—Global Oil Price Shock: Inflation and Fiscal Dynamics Trade-Offs

Eduardo Suárez, VP, Latin America Economics

+52.55.9179.5174 (Mexico)

esuarezm@scotiabank.com.mx

Recent developments beg the question: What is the impact of the oil price shock on the Mexican economy? Not surprisingly, the answer is quite complex and requires us to make several assumptions about the length and intensity of the conflict in Ukraine and the commodity price shock, as well as the Mexican government’s response.

As we have written in the past, the long-held stereotype that Mexico is an oil exporter no longer applies (chart 1). In fact, the recent Mexican oil trade deficit has been hovering in a USD 2–3 bn per month range. Our estimates suggest that if oil prices continue to hover around USD 100/bl, we could see that monthly oil trade deficit spike to around USD 5 bn. However, it’s also worth noting that if we look at the oil balance by sector, then the country’s public sector runs a surplus (much of it through crude oil), while the private sector runs a deficit which reflects its consumption of gasoline and petrochemicals.

The first impact of the shock for an oil importer will likely be the widening trade deficit as discussed. This already explains the year-to-date underperformance of MXN relative to regional peers, which have appreciated against the US dollar (BRL +12.0%, COP +6.7%, CLP +6.6%, PEN +6.2%) while the Mexican peso has depreciated by -0.3%. However, the more complex issue is whether the oil price spike will have a significant impact on inflation (+7.3% y/y in February), or whether public finances will absorb the hit. The direct weight of gasoline in Mexico’s CPI is 6.1%, but as the chart below shows, the Mexican government has absorbed much of the price hit by cutting gasoline taxes and applying a subsidy (chart 2).

These supports have already had a significant, though not critical, fiscal impact. Looking ahead, Valeria Moy from the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (IMCO) estimates that the cost of the gasoline subsidy the government is making would cost the fiscal accounts about MXN 330 bn if it stays in place for the rest of the year. Where does this figure come from? There are three elements to consider:

- First, Mexico levies a tax called IEPS (Impuesto Especial sobre Producción y Servicios) which for Premium gasoline would amount to MXN 4.63/liter, for Regular gasoline MXN 5.49/liter, and for diesel MXN 6.03/liter. Effective this week (March 12–18), for the first time all three taxes have received a 100% subsidy from the government.

- Second, on top of that, an additional subsidy of MXN 3.87/liter is being applied to Magna gasoline, MXN 2.75/liter to Premium gasoline, and MXN 5.24/liter to diesel.

- Third, in a single week, the cost to the public accounts from foregone income from the IEPS and the cost of the additional subsidy amounts to MXN 11 bn.

Clearly, the persistence of the oil price shock is critical. If global oil prices remain at current high levels, the government could decide to (i) reduce the oil price subsidy and allow a greater part of the shock to transfer over into oil prices, (ii) keep the status quo in place, or (iii) allow a full pass-through. Meanwhile, the government’s 2022 budget is based on three key assumptions which are unlikely to hold:

1. the budget’s yield curve is anchored on an expected average 28 day cete of 5.0%, while we kicked the year off above that and rates are still rising even as the government needs to roll over around USD 100 bn in debt during the year;

2. annual growth of 4.1%, whereas consensus is now closer to 2.0%; and

3. an annual increase in Pemex output of 4–5%.

Together, these assumptions are likely to lead to a miss of the public deficit target in the order of 0.5–1.0% of GDP. Our take is that Mexican public finances can manage an additional fiscal hit of 1.0% of GDP to keep the gasoline stimulus in place for the rest of 2022. However, as we have written in the past, if we look at long-term fiscal sustainability, a fiscal adjustment of around 1.5–2.0% of GDP will be required over coming years to stabilize long-run fiscal dynamics as analysis suggests debt levels are no longer anchored. This adjustment can take place either through a tax reform, boosting long run growth, cutting spending, or by increasing the primary surplus… or a combination of all the above. A one-year widening of the deficit would not be a serious problem, but it does make the fiscal adjustment that will eventually be necessary tougher.

Peru—Congress may Relent on Impeaching President Castillo, but Inflation is Relentless

Guillermo Arbe, Head Economist, Peru

51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

Congress has set March 28 as the date for impeachment proceedings against President Castillo. Although 76 members voted in favour of opening the proceedings, garnering the 87 votes needed for an actual impeachment is not likely. The proceedings present an odd situation, as President Castillo will need to defend himself, but, then again, he has already done so. On March 15, President Castillo addressed Congress at his own request, something that has only been done twice before in 22 years.

President Castillo’s intention appears to have been to deflate impeachment plans by offering to build bridges with Congress. He may have been successful, as the political mood in the country does seem to have shifted, at least for now. The following day, March 16, Congress decided not to “censure” —a type of impeachment—two Cabinet members, the Minister of Health and the Minister of Justice, and President Castillo’s speech the previous day may have influenced the vote. For now, Congress seems willing to give the Castillo Administration a reprieve. Going forward, the key to defusing the confrontation may be that President Castillo appoints government officials who are more acceptable and less controversial. Coincidentally, a decision taken by the Constitutional Court on March 17 to pardon ex-President Alberto Fujimori, detained since 2005, may also help distract the political milieu.

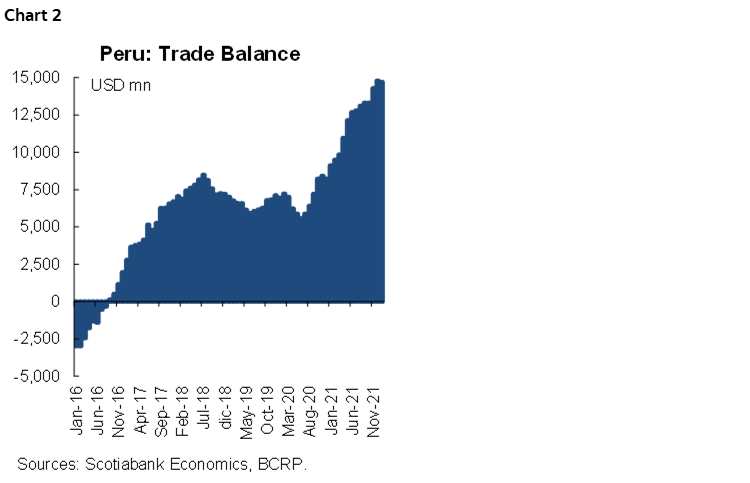

Yearly inflation rose to 6.2% in February. Inflationary pressure is likely to continue (chart 1), as Peru imports several goods whose prices are sensitive to the conflict in Ukraine, including oil, wheat, edible oils, maize, and fertilizer. Add to this, rising freight charges. These increased prices impact inflation through higher costs to Peru’s industry and agriculture. As a result, our forecast of 4.2% inflation for full year 2022 is no longer tenable, and we are raising it to 6.4%. This is a hefty increase. It also is fraught with uncertainty, as there is no telling how long the Ukraine conflict will last, and what the ultimate impact on global prices will be.

Our new forecast has inflation rising to the 7.5%–8.0% range over the next three or four months, and then declining slowly after that. The key assumption is that the impact of the conflict in Ukraine on world energy and commodity prices is fully absorbed after a few more months. If this is not the case, as it very well may not be, then we shall need to continue to revise our inflation forecast as events develop.

The BCRP raised its key interest rate by 50 bps to 4.0% on March 10. It also signaled a more aggressive monetary stance in its policy statement, indicating that it will consider “additional” modifications in monetary policy, if necessary. The BCRP highlighted its concern over the significant increase in global energy and food prices this year, and now expects inflation to converge to the target range in 2023 instead of in Q4-2022. Given its new stance, and our expectation that inflation will be higher for longer, we now expect the BCRP to raise its reference rate to 5.0% this year, from 4.0% currently. Furthermore, we expect this 100 bps increase to occur before mid-year. This is in line with our assumption that inflation will peak in the second quarter or early in the third. The BCRP is likely to hesitate before raising rates too high, in part because inflation expectations are rising only mildly, and in part because of the increasing risk that global events and, indeed, inflation itself, will begin to impact growth.

Meanwhile, the BCRP has continued to be complacent regarding the appreciation of the PEN, which has become range bound in the 3.70–3.80 area, as the period of tax payments by mining companies begins to end.

The conflict in Ukraine has been impacting Peru’s trade accounts more on the imports side than on the exports side. Only about 2% of Peru’s total trade is with Russia and the Ukraine. However, between 20% and 25% of imports are in fuel and commodity goods (soy, maize, wheat, fertilizer) that have been affected by events there. And higher freight costs have an impact across the board. Thus, the USD 1.0 bn trade surplus that Peru registered in January, which was the lowest in six months, can be taken as a harbinger of things to come. The 12-month rolling surplus stalled at USD 14.3 bn, below the December—and full year—figure of USD 14.8 bn (chart 2). January was, of course, before the Ukraine conflict began, but Russian saber rattling was already affecting markets.

Not surprisingly, imports soared 25.9% y/y, in January, outpacing exports growth of 16.2% y/y. The leading item was fuel imports, up 66%. Imports of fertilizer from Russia were up 61% y/y. In cumulative terms over the past twelve months, key imports of soy and maize were up 54% and 38%, respectively. Meanwhile, metal exports were up 52% cumulative over the past twelve months.

January GDP growth came in at 2.9% y/y, not all that bad considering political turbulence and the suboptimal business environment (chart 3). January’s GDP represented a 1.4% m/m increase over December. The progressive post-COVID-19 removal of mobility restrictions continued to support growth, as leading sectors in January included Hospitality (restaurants and hotels), rose 30.4% y/y, and transportation increased 9.2% y/y. Both together accounted for 1.2 percentage points of January’s 2.9% GDP growth. We expect growth in February–March to be mildly better than in January, at around 3% to 3.5% y/y, in line with our forecast of 2.6% GDP growth for full-year 2022 as the impact of a low base wears off, and inflation—as well as global risks—become more material.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.