HIGHLIGHTS

- Global semiconductor shortages have hit Ontario automobile manufacturers hard; in this note, we discuss the effects on the provincial economy and estimate potential impacts from further input product shortages and Ambassador Bridge disruptions.

- According to Wards Automotive Group, Canada produced only about 1.1 mn units last year, a decline of more than 260k (-19%) versus 2020, roughly 340k units below pre-shortage June 2021 plans, and the lowest total since at least 1985 (chart 1).

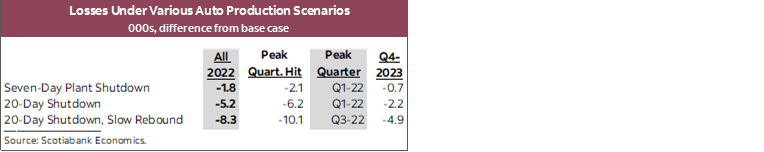

- More acute input product shortages or lingering Ambassador Bridge blockage-related effects present further downside risk to the production outlook; we estimate that these could reduce Ontario growth by 0.1 to 0.3 ppts this year1 (chart 2).

- Similarly, our model of the Ontario economy associates bridge and supply chain-related auto production disruptions with total job losses of between 2k and 8k in the province in 2022.

- Auto production is a vitally important sector in Ontario: prior to the pandemic, it represented about 16% of provincial manufacturing output, while vehicles and parts made up about one-third of exports and around 2% of GDP.

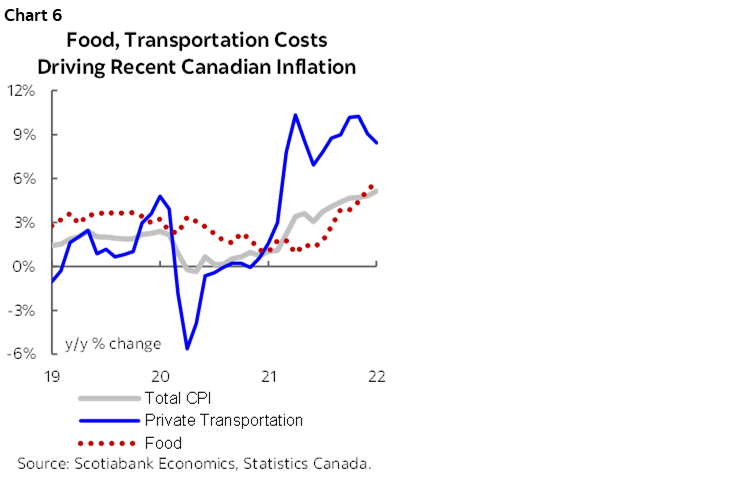

- The risk of further surges in Canadian food and car prices—already under intense pressure because of global supply chain issues—is real.

THE ENGINE OF ONTARIO’S ECONOMY

The auto industry is a key component of Ontario’s economy. In 2019, 1.9 mn light vehicles were produced in Canada—all in Ontario—by five automakers. The province also supports an extensive supply chain with over 700 parts firms and more than 500 tool, die and mold makers in support of regional auto production that saw 16.8 mn vehicles produced in North America in 2019. A frequently quoted statistic states that a vehicle part crosses the US/Canada border seven times before production is complete.

The auto sector’s contribution to the province’s economic output was estimated at about 2% of GDP before the pandemic. The sector accounts for about one-third of the province’s total exports. Direct jobs in the industry are estimated at around 100k while indirect jobs are estimated to be seven-fold. According to the Ontario government, over 30 universities and colleges provide auto-specific training and research programs, while 200+ companies are developing connected and autonomous vehicle technologies.

PRODUCTION IN LOWER GEAR

The industry has withstood turmoil and transitions in the past. Since NAFTA was signed in 1994, Canada’s share of light vehicle production dipped from 16% to just under 12% in 2019. Mexico was the net-winner with its share growing to 23% (from 6%), while the US saw its share drop to 64% (from 78%) in the same period. More recently, protracted re-negotiations of NAFTA—along with steel and aluminum tariff wars—under former US President Trump created substantial uncertainty for the industry. While the end result was largely positive (higher regional and labour value content requirements) for Ontario production, announcements of plant closures in Ontario ensued that already would have seen an output drop of about 100k vehicles in the province in 2020 prior to the pandemic.

The pandemic gutted auto production across the continent in 2020. First waves of COVID-19 saw full-stops in auto production in the spring of 2020 and supply chain disruptions continued to impact output even after plants started reopening. By our estimates, 4 mn fewer vehicles were produced in 2020 in North America relative to our pre-pandemic forecasts, while sales fell 3 mn short.

Shortages of semiconductor chips—a key input into auto production—pushed output even lower in 2021, despite the fact that economic growth and consumer demand surged in the first year of the recovery. The root causes of these shortages are complex (discussed here), but one factor was a massive undershoot in auto manufacturers’ chip order books at the onset of the pandemic against a stronger-than-anticipated rebound in auto demand, which caused delivery times to skyrocket from three to nine months. According to data from Wards Automotive Group, Canada produced only about 1.1 mn units last year. That figure: represents a decline of more than 260k (-19%) versus 2020, is a reduction of roughly 340k units from June 2021 pre-shortage plans, and is the lowest annual total since at least 1985.

Canada’s 2021 auto production plunge contrasts with reopening-assisted annual increases in Mexico and the US (chart 3). Faced with severely relatively limited numbers of a range of input products, Canadian producers have shifted their limited production capacity towards a smaller number of higher-margin vehicle types and products such as pickup trucks and SUVs. Wards has pencilled in a 30% production increase in 2022, but the projected annual level for this year is more than 380k units lower than anticipated in June 2021.

Blockades at the Ambassador Bridge that connects Windsor, ON to Detroit, MI present downside risk to this already challenging automotive sector environment, even though the route has reopened. During the past five years, about 20% of Ontario’s vehicles and parts imports are sourced from Michigan; last week, after just a few days of disruption, Honda and Toyota plants in Southern Ontario shut down in response to severely limited input product availability. Though the bridge has reopened, it will likely take time to return to the pre-disruption pace of trade and production. Moreover, there are potential business confidence and reputational impacts that could impede Canada’s efforts to establish and grow a vibrant electric vehicle industry over the long-run.

SIZING UP IMPACTS ON THE ONTARIO ECONOMY

While Ontario’s economy is still in position to experience a strong expansion over 2021–22 with easing of and adaptation to COVID-19 restrictions expected to proceed, weakness in vehicle production has prompted downward revisions to provincial growth forecasts over the last six months. The impacts of automobile output cuts first became apparent in Q2-2021, when they contributed to a nearly 20% (q/q ann.) plunge in real Ontario exports, which underpinned the province’s 5% (q/q ann.) economic contraction in that quarter. In our April 2021 forecast—the last set of projections before semiconductor issues emerged—we assumed a 2021 Ontario expansion of more than 6%—slightly stronger than the national average. In January 2022, once the impacts of dramatic production reductions and strict third pandemic wave lockdowns were clearer, we anticipated real gains of just 4.3%.

To quantify what might happen if supply chain disruptions further impede vehicle production, we use our model of the Ontario economy. It is a general equilibrium model similar to semi-structural models used at the Bank of Canada, and projects key quarterly components of real GDP like consumption, business investment, and international and interprovincial trade based on the historical economic accounts data produced by the Ontario government. Total vehicle production—sourced from Wards Automotive data—is a key driver of Ontario international export volumes.

To assess the impacts of additional potential production disruptions, we devised three auto production scenarios (chart 4, p.2). The first is based on a seven-day closure of Honda and Toyota plants—the same duration as the initial bridge disruption—with an immediate return to pre-blockade output. These companies have announced temporary blockade-related shutdowns; last year, affected plants made up about half of Canadian production. The second scenario assumes production outages last another 13 days until the end of February. The third and most dire scenario assumes February shutdowns plus a slower rebound in production levels as a result of more severe, extended semiconductor shortages. This scenario roughly aligns with the case of the most persistent supply chain challenges detailed here, and is consistent with AutoForecast Solutions’ recent increase in forecast numbers of vehicles cut from production schedules at North American factories. We also run a supplementary scenario that assumes vehicle production in line with pre-semiconductor shortage projections from Q2-2021 onwards.

On the basis of that approach and those assumptions, we estimate that the blockades could reduce Ontario growth this year by between 0.1 ppt (in the case of the mildest and shortest-lived disruption) to 0.3 ppt (in the case of longer-lasting supply chain issues). In all scenarios, there would be a stronger-than-baseline rate of expansion in 2023 because of the auto production bounce-back. However, absent capacity to increase production beyond pre-disruption rates and with other sectors of the economy likely to take time to adjust to the shock, the level of real GDP would remain below that projected before disruptions (chart 5, p.2). Our model also predicts that if auto production grew at pre-semiconductor shortage rates beginning in Q2-2021, real Ontario GDP would be over $30 bn higher than our base case forecast in Q4-2022.

Along the same lines, our model associates blockade and supply chain-related auto production disruptions with total job losses of 2k to 8k across the Ontario economy in 2022. As with GDP, the rate of job growth would climb above our baseline prediction in 2023 because of the arithmetic of the auto production bounce-back, but the level of total employment would stay below pre-blockade forecasts through 2023 (table).

In addition to growth impacts and job losses, the risk of further surges in Canadian food and car prices—already under intense pressure because of global supply chain issues (chart 6)—is real. Alongside its role in the automotive sector, the Ambassador Bridge transports a significant amount of food and agricultural products from the US Industrial Heartland to Southern Ontario each day. This adds to the broader inflationary backdrop that began with a concentrated shortage of semiconductors and has since expanded to include a dearth of a range of products as well as labour.

1 Forecasts completed January 19, 2022.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.