- Chile: Inflation will continue its trip back to target in January

- Peru: Monetary policy to remain steady as inflation fades; Petroperu grows as a fiscal concern

CHILE: INFLATION WILL CONTINUE ITS TRIP BACK TO TARGET IN JANUARY

At Scotiabank Economics, we project January inflation to be between 0.4 and 0.5% m/m, mainly explained by the positive contribution of food, although it ensures that the year-on-year variation continues to approach the target of 3%. Along these lines, our projection is that the inflation target will be reached in March of this year, a similar view to that adopted by the board of the BCCh after recognizing the downside surprise in December, both in headline and core inflatoin. This has also influenced the view that the Board has on the trajectory for the benchmark rate, which will be updated at the April IPoM and which, according to the minutes of the January meeting, will consider that the reference rate will reach its neutral level in the second half of this year. At Scotiabank, we do not rule out that this level will be reached towards the middle of the year if there are no inflationary surprises in the January and February CPI prints.

—Aníbal Alarcón

PERU: MONETARY POLICY TO REMAIN STEADY AS INFLATION FADES; PETROPERU GROWS AS A FISCAL CONCERN

The BCRP can breathe more easily now. After two years, inflation has finally returned (albeit just barely) to its target range. In January, 12-month inflation came in at 3.0%, the cusp of the BCRP target range. Monthly inflation for January was nil.

With inflation at the door of its target range, the question is whether this might tempt the BCRP to lower rates more aggressively on February 8th, say by 50bps, rather than its usual monthly pace 25bps.

Don’t bet on it. It’s tempting, it’s true, as there seems to be so much light between the current reference rate of 6.50% and inflation expectations, which currently stand at 2.8%. That’s a real rate of nearly 3.75%, which is significantly above the 2.0% which the BCRP considers the neutral rate. Add to this the statement made last week by the BCRP’s chair, Julio Velarde, that his balance of concerns is shifting from inflation to growth, and a case can be made for the BCRP to be more aggressive when it meets next week.

So, why not? The first reason, as we’ve mentioned before, is that the BCRP has yet to become more accommodating in providing liquidity to the system. This reveals that it still has concerns. To begin decreasing the reference rate more aggressively without easing liquidity constraints would generate a policy mismatch that would be hard to understand. Furthermore, the BCRP is currently in its comfort zone and there is no hurry to vary its policy. The BCRP can lower rates by 25bps per month throughout most of the year without raising eyebrows. In contrast, if the BCRP were to lower the reference rate by any amount except 25bps (say 50bps), this would create unnecessary turbulence in market expectations, and henceforth put the BCRP under pressure to continue reducing rates aggressively. We do not see the BCRP putting itself in this position.

Let’s see, we seem to be forgetting something here… oh, yes! El Niño! How could we forget what we long considered the main risk factor for 2024? Well, that’s because the risk has all but disappeared. As we approach the mid-point of the normal El Niño period, there has been no impact at all so far in 2024. Moreover, the local El Niño monitoring system, ENFEN, now reports that the El Niño is likely to be weak, tending to non-existent.

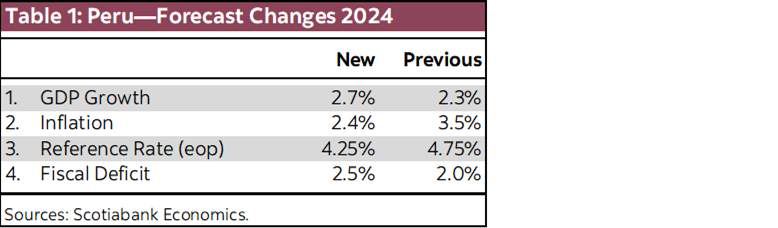

The change in outlook regarding El Niño has brought about a change in outlook for the economy in 2024. We’ve reported our new forecasts in previous Latam Dailies and Weeklies as we’ve made them, but it might be helpful if we provide a summary of the main changes here (table 1).

On a final note, the plot thickens in the saga of the Petroperu’s financial troubles. Fitch Ratings announced last week that it had downgraded Petroperu’s rating to B+ from BB+. This comes after the government of Peru denied Petroperu’s request for a USD2.5bn bail-out program to service its USD6bn debt. Instead, the government set up a committee to seek a solution. Still, the message that was sent is clear, the government will not give Petroperu a blank check, or any check at all if it can be avoided. It is this lack of clear government backing for Petroperu’s debt which led Fitch to downgrade its debt.

Petroperu’s downgrade raises the question of what it may mean for Peru’s own sovereign debt ratings. Fitch stated that changes in Peru’s sovereign debt ratings would impact Petroperu’s ratings but did not mention an inverse relationship. Our read is that that Fitch would not automatically change its sovereign debt rating for Peru based on Petroperu’s downgrade per se. But, at the same time, the developments overall imply the recognition that the very existence of Petroperú’s financial quandaries constitutes a degree of risk.

Down the line, much will depend on how events play out. It’s hard to see the government simply allowing Petroperu to fail, which would be scary on different levels. So, what it is likely to come down to is how great an ability the government has to rescue Petroperu, while avoiding having this rescue turn into an overriding and persistent burden.

—Guillermo Arbe

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.