SUMMARY

- Our updated economic forecasts assume that the Russia-Ukraine war will: create stagflationary conditions for commodity importers, exacerbate existing inflationary pressures, and prompt faster monetary policy tightening in North America.

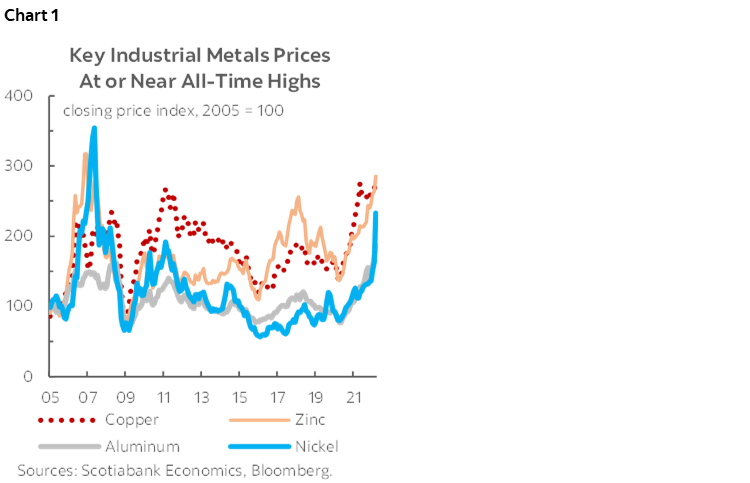

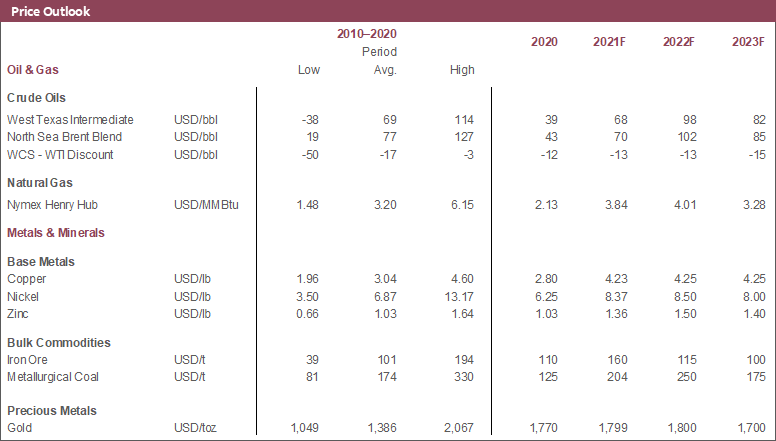

- Prices for all the industrial metals we cover have skyrocketed in response to Russian supply fears, but nickel’s rise has been the sharpest (chart 1); we expect them all to continue to track Russia-Ukraine conflict developments and sentiment.

- Crude values continue to whipsaw; our base case projections assume that the geopolitical risk premium will keep oil prices very well supported this year.

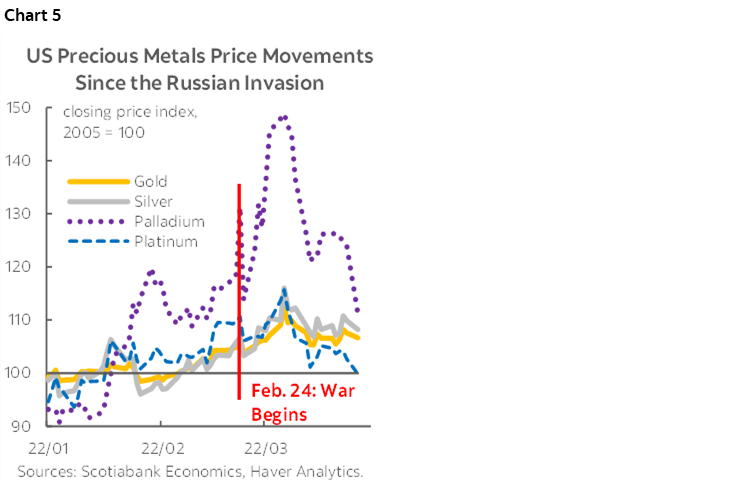

- We expect precious metals to benefit from global uncertainty and inflationary pressures on an ongoing basis, though they lost steam at the end of March amid apparently constructive peace talks and expectations of a more hawkish Fed.

WAR IMPACTS: LOCALIZED WEAKNESS, UNCERTAINTY, EVEN MORE INFLATION

We have now incorporated impacts of Russia’s attack on Ukraine into our economic forecasts; at this early stage, we assume differing impacts on different economies. We expect those geographically closest to the conflict and most reliant on Russian and Ukrainian commodity imports—notably those in Europe—to experience stagflationary drags. Meanwhile, rising values of external shipments will likely bolster terms of trade for net commodity exporters like Canada. For all countries, volatility and uncertainty created by the conflict will likely weigh on investor sentiment and delay capital outlays.

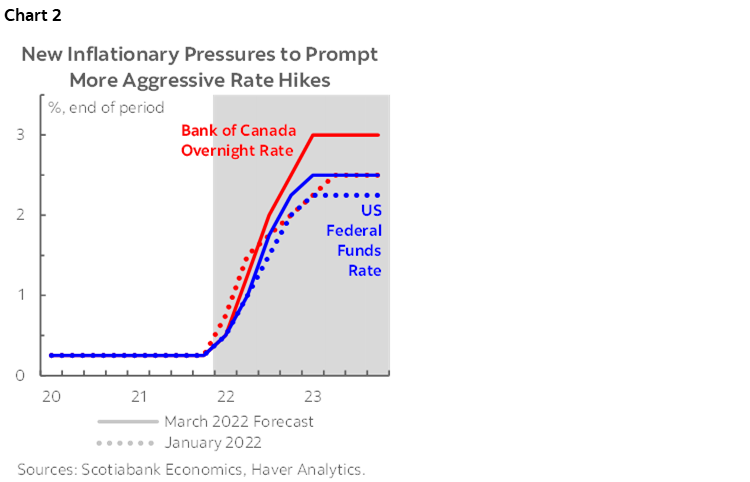

Effects on inflation are perhaps more significant. The war is already hindering access to key commodities, adding to multi-decade-high price pressures already experienced as a result of ensnarled global supply chains. Consequently, we have revised inflation forecasts higher in nearly all countries within our coverage universe, and now assume annual CPI increases of 5.9% and 7.7% in 2022 in Canada and the US, respectively—both the highest since the energy crisis of the early 1980s that followed the Iran-Iraq War. While monetary policy orthodoxy argues for looking through supply shocks, on the basis of the strength of price gains to date and potential downside risks associated with higher inflation, we have penciled in more rate hikes from the Bank of Canada and Federal Reserve (chart 2).

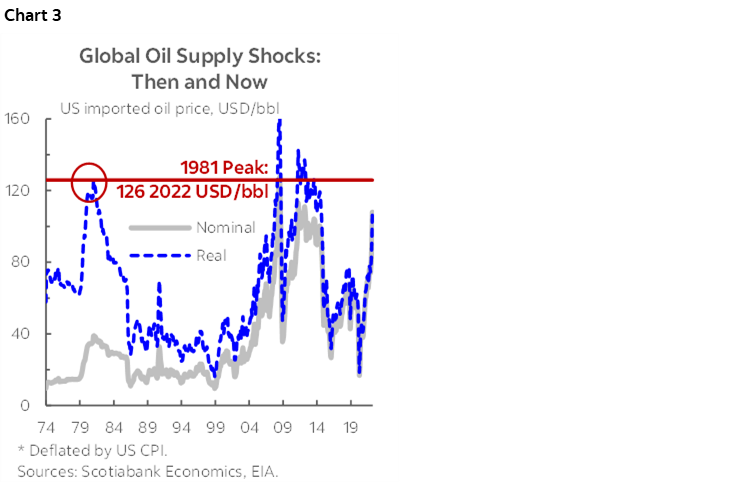

Acknowledging that downside risks are real, we do not forecast a US recession at this time. Recent yield curve movements do not prove that an economic downturn is imminent. There is pent-up pandemic demand across the global economy that could help offset the inflation and rate hike hit to consumer spending. Other indicators like deeply negative real policy rates and 10-year bond yields and very low inventory-sales and household debt service ratios suggest resilience. Finally, adjusting for inflation, recent oil price spikes are not as large as those in the early 1980s or late 2000s (chart 3, p.2). Thus, while supply constraints could worsen and global crude benchmarks have briefly tested peak inflation-adjusted historical levels, greater US oil independence may insulate the world’s largest economy from the same stagflationary drag seen in the 1980s.

INDUSTRIAL METALS CONTINUE TO SURGE, LED BY NICKEL

Though prices for all the industrial metals we cover have skyrocketed in response to Russian supply fears, nickel’s rise has been the most striking; we expect them all to continue to track Russia-Ukraine conflict developments and sentiment. Nickel’s surge is an understandable result given that Russia accounted for an outsized share of about 10% of global production over the last two years. In the near-term, we expect more volatility following the trading stoppages and record intraday pricing that occurred this past month given sensitivity to the ongoing war and reports of large short positions. However, ramped-up nickel pig iron production from Indonesia—key to our January forecast of more moderate nickel price gains—may eventually provide some relief.

Industrial metals market watchers are also training their eyes on economic conditions in China—the world’s largest consumer—which have weakened of late. Alongside fears of a real estate sector slowdown—already factored into our forecasts—China is in the midst of its largest pandemic wave by far and now under some of the strictest and broadest COVID-19 lockdowns since the start of the pandemic. This may be limiting copper price gains, though the red metal—in the midst of tight supply-demand balances before the Russian invasion—recently breached the all-time high reached in May 2021. Iron ore also continues to be held back by soft steel production numbers from the 2022 Winter Olympics period. We believe China’s monetary and fiscal policies will become more accommodative over the next few months, which will help the economy approach its recently announced 5.5% real growth target for 2022.

MUTED SUPPLY RESPONSE AS OIL PRICES CLIMB, VOLATILITY REIGNS

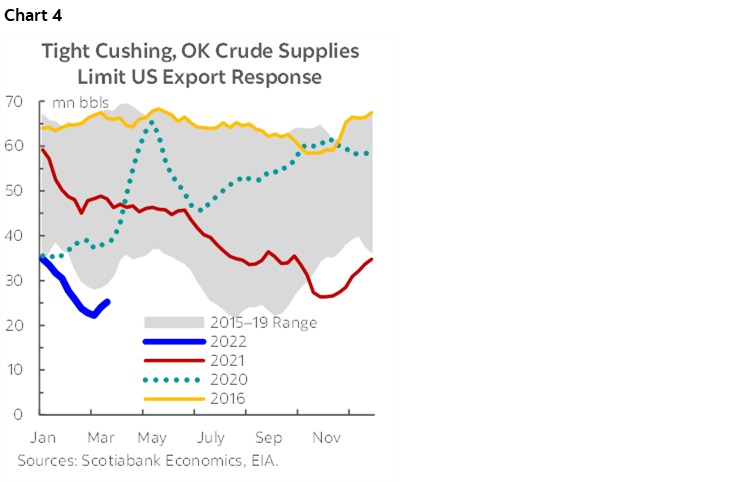

Crude values continue to whipsaw in response to Russia-Ukraine conflict news flow; our interim base case projections assume that the geopolitical risk premium will continue to keep oil prices very well supported this year. Closing values for WTI ranged from 95 to 124 USD/bbl in March 2022; for Brent, the range was 98–128 USD/bbl. Combined with signs of weaker demand from China and potentially constructive Russia-Ukraine peace talks, crude values eased towards the end of the month. To the extent that these trends continue, we could see further cooling, though sanctions on Russia are still in place. Questions also remain about the ability of OPEC members to ramp up output capacity, and key producers Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates thus far appear hesitant to boost production. Moreover, the capacity for American product to fill any voids is limited by ongoing capital discipline in the US shale patch and tight supplies at the key Cushing, Oklahoma hub (chart 4). As well, steep backwardation of the WTI forward curve incents quick turnover local sales over longer-delivery oil exports.

Supported by the same forces as the light oil benchmarks, WCS has been trading between 80 and 110 USD/bbl this month—its highest level since 2008. In recently released provincial budgets, both Saskatchewan and Alberta pencilled in solid production increases for the coming year—the latter expected to add to the record attained in 2021—and the IEA’s March forecast assumed solid gains for Canada in each of the next two years. With such strong pricing, we expect to see continued incentive to ramp up production. However, broad-based labour shortages and the need to de-bottleneck operations at crude facilities may hinder producers’ ability to do so quickly. We also suspect that the tight supply-demand environment will prompt greater numbers of crude-by-rail shipments in the coming months.

Looking longer-term, March 2022 also marked the release of the Government of Canada’s new climate change plan. The blueprint includes a pledge to cut oil and gas sector emissions by more than 40% from 2019 levels by 2030. Details of plans to cap and reduce emissions will be provided later this year following consultations with industry players and stakeholders. These were widely anticipated and should have little impact on market dynamics.

UNCERTAINTY AND INFLATION STILL BUOYING PRECIOUS METALS

Global uncertainty and inflation continue to be broadly positive for bullion—its March 2022 average near 1,950 USD/oz was the highest in any month since August 2020 (chart 5, p.2) when it reached an all-time high. However, values of the yellow metal underwent some downward pressure towards the end of this month as financial markets increasingly began to price in a more aggressive monetary tightening path from the US Federal Reserve. The Russian Central Bank also now appears less concerned about the depletion of domestic inventories, having resumed buying bullion from local banks following a two-week halt (albeit at a fixed price). Silver—influenced by many of the same factors—followed suit. Going forward, we expect values for both metals to continue to mirror these forces, with still-low rates, persistent inflation, and heightened uncertainty likely to keep the yellow metal well supported this year.

Other precious metals such as palladium and platinum have experienced similar but more exaggerated price movements since Russian aggression began. The US Geological Survey estimates that Russia accounted for an outsized 40% of combined 2020–21 global palladium production, and about 12% of world platinum output over the same period.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.