GoC bond purchases were reduced to $3B/week from $4B+

Forecast upgrades were applied across the world into Canada

Spare capacity now forecast to shut in 2022H2…

…with inflation sustainably on target by then

The inferred policy bias supports ending QE this year…

…and hiking possibly earlier and faster than markets expect

Is the BoC signalling a run-hot inflation bias?

The Bank of Canada met almost all of our expectations for a hawkish taper accompanied by pulled forward guidance that spare capacity would shut in 2022 with inflation above target next year. Where they surprised was concentrated in a decision to leave the maturity composition of purchases unchanged within the tapered flow of Government of Canada bond purchases down to C$3B/week as I had thought they might have extended maturity while tapering.

Markets reacted by driving CAD appreciation of about 1½ cents to the USD as the currency vaulted to the top of the class among currency performers to the USD. Canada’s yield curve jumped by 2–4bps from 2s through 10s and flattened across 10s30s because of the concentrated effects of the taper, more hawkish implied forward rate guidance and long-end optimism that inflation risk may be contained somewhat by a BoC narrative shift.

Overall, I’m impressed. I think the BoC has done the right thing here. One can quibble that they likely should have adjusted their narrative more quickly as vaccine trials were reported and fiscal stimulus plans took off in the US and Canada alongside evidence of a more resilient economy than they feared. One should be concerned that sticking to this bias for too long resulted in an excessive commitment to stay on hold to 2023. Nevertheless, they are courageous enough to now stand apart from the pack of most global central banks with their changes and guidance today. The suite of evidence suggests that the emergency conditions have passed or are increasingly passing and so should emergency stimulus that is at risk of doing more harm than good.

It is extraordinarily unfortunate, however, that a leak by one media outlet ahead of time botched the headlines and sparked some market participants to position cover into the BoC communications only to get whipsawed when the real headlines hit. This may have involved a material financial consequence to varying parties and should merit further investigation by the BoC and others.

So what did the Bank of Canada do in the suite of communications including the statement (here), Monetary Policy Report (here), the opening statement to Governor Macklem’s press conference (here) and the Q&A session?

Taper Delivered

They tapered down to C$3 billion of Government of Canada bond purchases per week from $4B+ as expected. The reduction will be effective next week. Note that the ‘+’ part of the purchase guidance has now been struck out which implies that the theoretical adjustment is even greater than the expected $1B reduction as it goes from an average over $4B/week down to $3B.

Conditional Purchase Guidance Maintained

Forward guidance applied to the purchase program was generally left unchanged. The BoC repeated the conditional nature of future decisions by stating “Decisions regarding further adjustments to the pace of net purchases will be guided by Governing Council’s ongoing assessment of the strength and durability of the recovery.”

I would advise pencilling in a further taper at the July MPR meeting. If Governor Macklem continues to adhere to prior guidance that net purchases would end before spare capacity is eliminated then that probably counsels fully ending purchases later this year conditional upon when the output gap shuts (see next point).

Spare Capacity to Shut Next Year

The BoC now forecasts that spare capacity will close in 2022H2 instead of prior guidance this wouldn’t happen until 2023. Our forecast is that the output gap will shut later this year. Four considerations likely contribute toward explaining this difference and how BoC guidance could change again from here.

For one thing, we’re incorporating more US and Canadian fiscal stimulus—especially the former—than the BoC is so far. The BoC does not appear to be factoring in assumptions on how much of the proposed American Jobs Plan and pending American Families Plan may pass through Congress and hence how much may leak out to Canada. Fact upon passage rather than conjecture during the horse trading is likely the operating belief here. Nevertheless, a street shop doesn’t have the luxury of putting on horse blinders and assuming away 100% of the trillions that the Biden administration is talking about. Therefore, when the BoC says in its MPR that “Fiscal stimulus starts to wind down in 2022, creating a drag on growth,” treat it as a forecast assumption waiting for a positive reassessment that could close spare capacity earlier than they say.

The BoC also has to factor in the full amount of the Canadian Federal Budget’s $101B of added stimulus over three years instead of its forecast assumption—set before the Budget’s release—that it would deliver $85B.

Third, the BoC raised its estimates of how fast the supply side of the economy will grow as actual GDP growth takes off. They did so through a modest upward adjustment to potential GDP growth but the range they are using is still miles wide. You can check out the numbers in table 2 of the MPR, or take my word for how they think potential will land somewhere between St. John’s and Victoria throughout the forecast horizon. Time and actual data across a suite of indicators will tighten up this understanding.

For another, the BoC is likely being cautious in altering its narrative more slowly than a street shop has to and doing so in increments toward a gradual bias shift. Macklem put that this way: “We’re not going to count our chickens before they’ve hatched.” True, but every good farmer still needs to plan ahead. Given uncertainty and the fact that central bankers get paid in asymmetrically flat fashion to manage risk not opportunity, they tend to avoid abrupt changes in views and skew the risks to the downside. To go from spare capacity shutting in 2023 instead of later this year would have whipsawed markets to an even greater extent even if the BoC thought it possible. Instead, the BoC took a first step in that direction today and abandoned one of the pillars of its policy stance since the pandemic began that it would take into 2023 to close spare capacity and by corollary rates would be on hold at least until then. In its attempt at explaining away housing strength as entirely fundamentals driven, the BoC is seeking to absolve itself of any responsibility for sparking housing excess through an overly generous commitment period that was slow to adjust to new information since last Fall. The signal to borrowers is to be on greater guard now.

Positive Global Forecast Revisions

In order to arrive at earlier closure of spare capacity, the BoC upped its growth forecasts across the board.

- World growth was pulled forward and is now forecast to be 6.8% this year (5.6% prior), 4.1% next (4.6% prior) and 3.3% in 2023 (3.9% prior).

- Ditto for US growth at 7% this year (from 5%), 4.1% next year (from 3.9% and 1.3% in 2023 (from 2.0%). Again, be careful here in that the implied slowing assumes away the likely trillions in additional US fiscal stimulus that is likely to be forthcoming.

- China was also upgraded to grow by 9.5% this year (from 8.4%) and slightly lower in 2022 and 2023 (5.3% in both years).

- Other global forecasts were relatively little changed and of less relevance to Canada.

Positive Canada Forecast Revisions

Canada’s macro forecast was upgraded. The BoC now thinks Canada will grow by 6.5% this year (from 4.0% previously), brought 2022 a bit lower to 3.7% (from 4.8%) but raised 2023 to 3.2% (2.5% prior). The takeaway is that the BoC thinks actual GDP will surpass even the upper end of its ranges for potential GDP in each of 2021, 2022 and 2023. By corollary, the output gap increasingly swings into excess aggregate demand throughout their projection horizon. While it’s true that the range of potential GDP is highly uncertain (and so is actual GDP in both directions…) the BoC is betting even without factoring in additional US fiscal stimulus that the economy will have enough momentum to drive a rising push into excess demand conditions throughout 2021–23 and that’s a pretty hawkish message.

Inflation Forecasts Revised Higher

Now here’s where things get even more interesting. The BoC upped its inflation forecasts to 2.3% (1.6% prior) in 2021, 1.9% in 2022 (1.7% prior) and 2.3% in 2023 (2.1% prior). On a higher quarterly frequency basis it expects CPI inflation to surpass 2% on average starting from 2021Q4 through to the end of its projection horizon in 2023Q4.

But what does it think of core? The BoC does not formally forecast core inflation measures. It nevertheless probably has a similar view on core to that which it presents for headline inflation given the BoC’s tendency to treat core as the operational guide to its inflation targeting framework because headline and core measures have a tendency to converge upon one another over time. Box 5 on page 18 of the MPR, however, adds considerable near-term doubt at least in terms of how the BoC views current core inflation. Basically, they point to multiple measures of core inflation even beyond the trimmed mean, weighted median and common component gauges and tend to exhibit a bias toward measures that are lower than the trimmed mean and weighted median measures for reasons explained in the box. If there is a way to over-complicate the measurement of inflation in a scattered approach then the BoC is definitely up to the task! The takeaway is probably that they think true core inflation is lower than what is derived from the average of the three measures published by Statistics Canada, but the suite of them on average are probably expected to converge to target if not rising above target throughout the forecast horizon.

What is the BoC Signalling About an Inflation Overshoot?

How can that happen you say? Why would the BoC forecast three years of inflation over 2%? Doesn’t the BoC target 2% in symmetrical fashion? Macklem was asked this question in the press conference and whether an overshoot reflects a desire to make up for prior undershoots in a flexible average inflation targeting sense. Of course his answer was no, that instead the overshoot is a consequence to forward guidance that they will not act pre-emptively by hiking ahead of the achievement of the inflation target rather than around when it occurs. I don’t buy that. In fact, it’s rather Fed-like imo. Macklem’s response gets harder to accept the further out in the forecast horizon that inflation is forecast to overshoot since it implies that the BoC is either going to tolerate it or thinks it will be incapable of staying on target. So what’s going on? We can’t ignore the possibility that after years of undershooting the inflation rate (see my earlier BoC deck), the BoC is finally trying to operationalize the theoretically symmetric nature of the 2% target by indeed allowing for a prolonged modest overshoot. If so, then the BoC is following the Fed in that regard and should say so. We’ll see when the announce the results of their strategic review later this year.

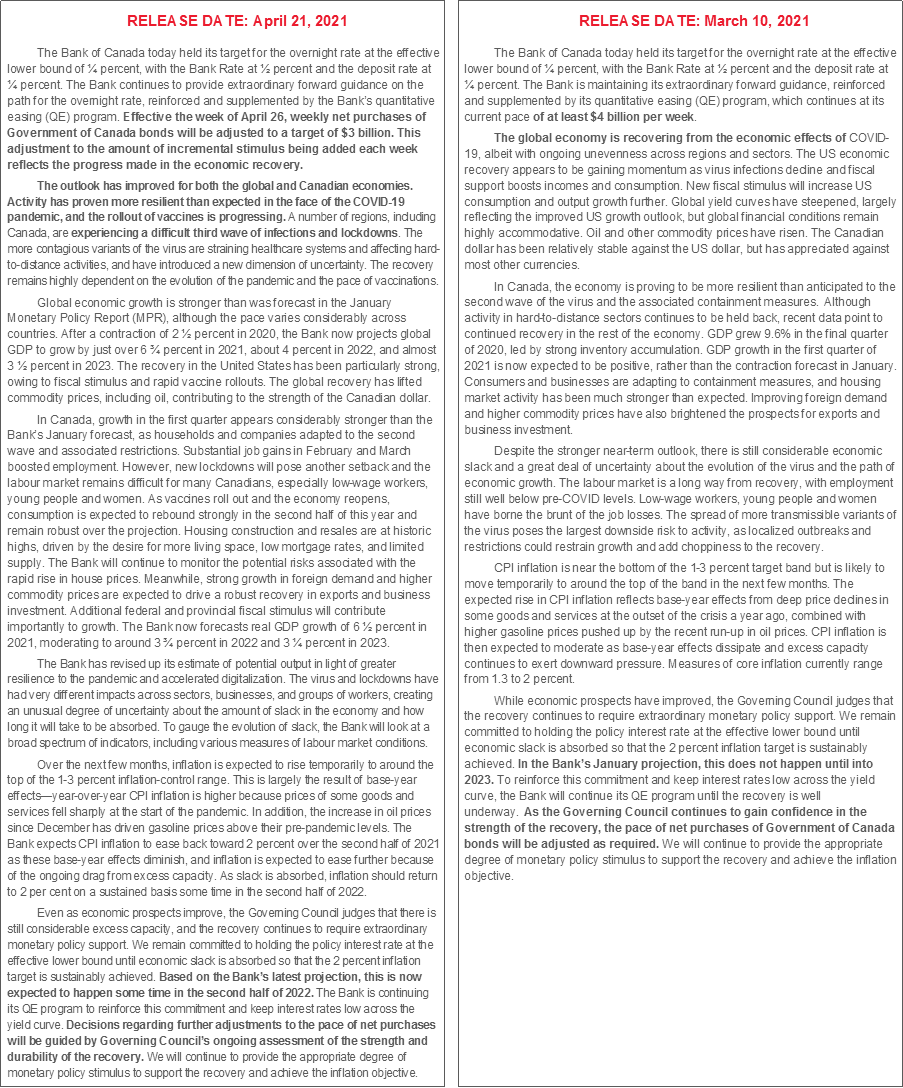

Please see the accompanying statement comparison.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.