The Province of Ontario has provided its first multi-year economic and fiscal outlook since the pandemic struck. It adopts a scenario approach to reflect the wide range of uncertainties over the planning horizon.

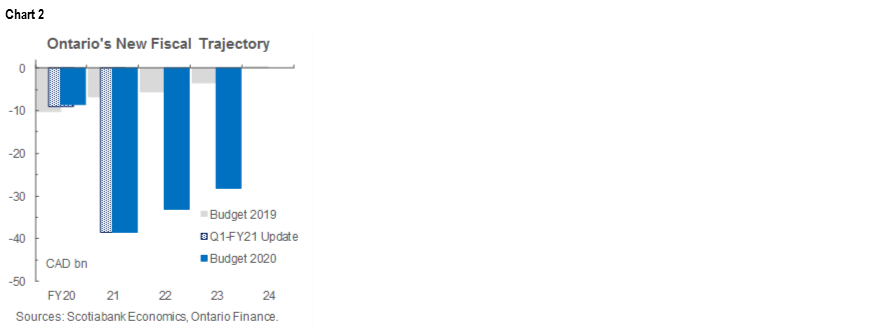

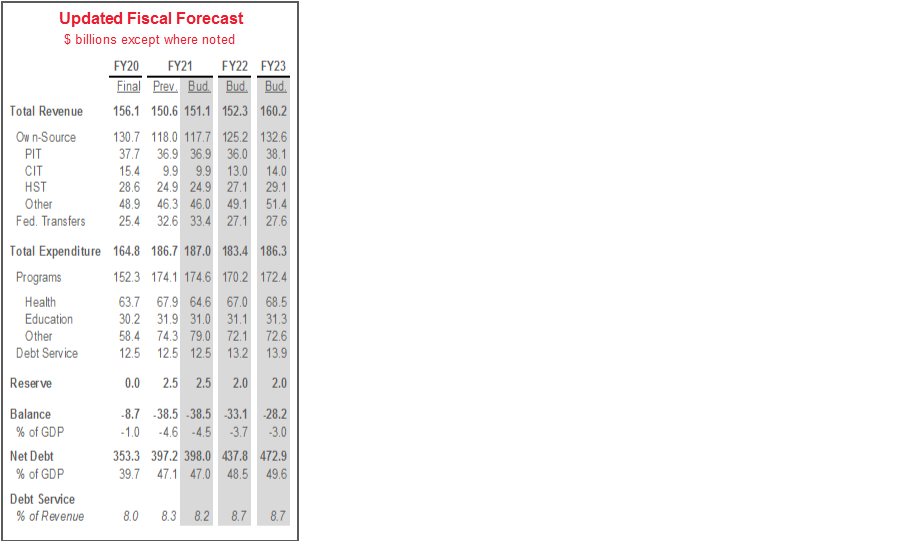

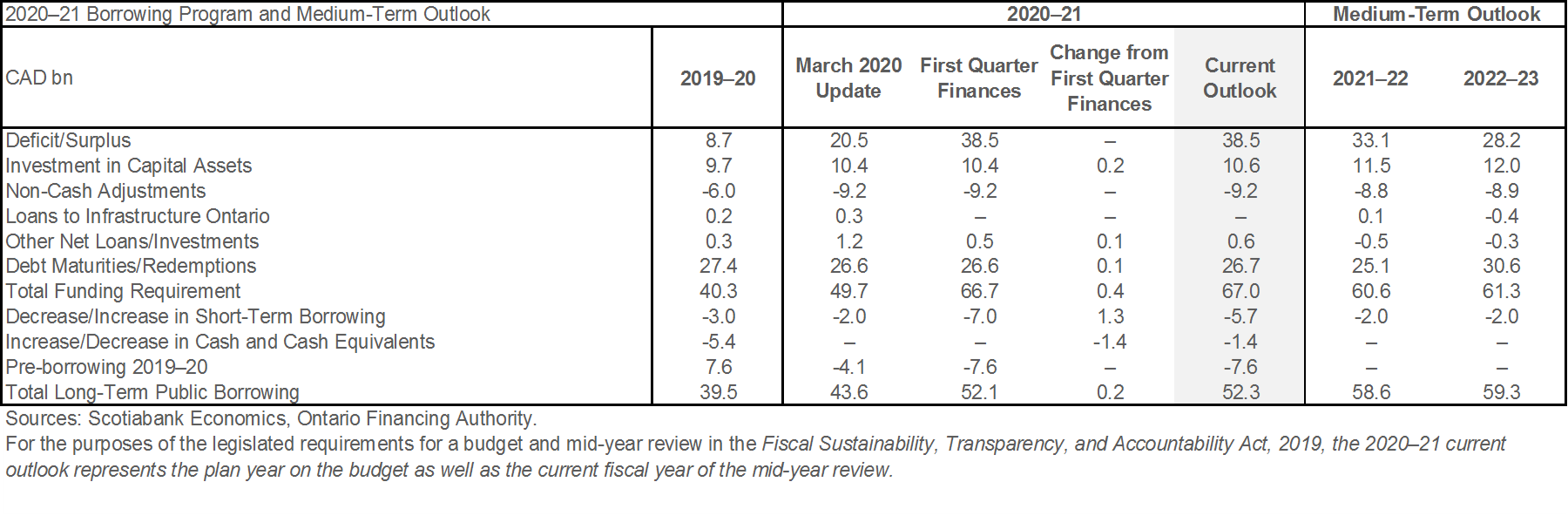

Not surprisingly, COVID-19 is expected to take a significant toll on the provincial economy and its finances. The province anticipates a deficit of $38.5 bn in FY21, with red ink declining thereafter, amount to $33.1 bn and $28.2 bn in FY22 and FY23, respectively.

The fiscal path is largely calibrated to economic conditions as the province only expects to close its pre-pandemic output gap in 2022, with slack persisting well-into 2023. This suggests targeted policy supports are appropriate over this horizon.

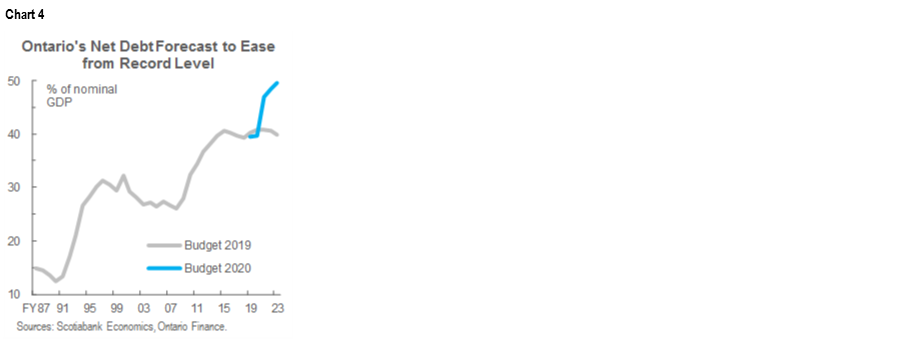

This will bring net debt to a record 47.1% of GDP in FY21 and it will continue to increase modestly over the horizon to almost 50% of GDP by FY23.

Nevertheless, debt remains sustainable and borrowing activity is expected to continue to be well-subscribed, but as the recovery takes hold, there will be increasing pressure to bend the debt trajectory downward over time.

With ample conservatism built into the projections, this may be easier when significant uncertainties abate by the time of the next budget this winter.

OUR TAKE

The province has tabled a prudent fiscal outlook in light of many remaining uncertainties. Despite a faster than expected early rebound from the first wave, many parts of the province are now facing second waves. While lockdowns are proving more targeted, risks and uncertainties still remain over the budget horizon. Prudence is built in through conservative growth forecasts, some revenue sensitivities (notably personal income tax), and sizable contingencies and reserves. In a downside scenario, these may very well be needed, but in a more optimistic scenario, deficits could come in smaller over the horizon—and importantly increases in net debt levels could reverse naturally.

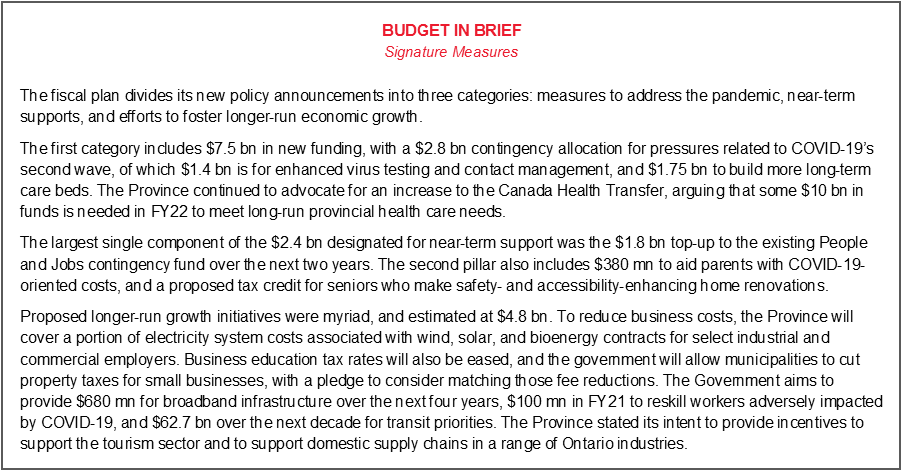

Budget allocations are also relatively contained and balanced. New allocations amount to $15 bn over three years—or about 1.6% of GDP over three years. (See Box in Annex for budget highlights.) Half of this is related to pandemic spending including under the largely temporary themes of protecting and supporting Ontarian households during the pandemic. These are for the most part temporary. Investments to slow the spread can stave off worse outcomes, while other measures such as additional transfers to families should be stimulatory in the short term. About a third of new spending ($4.8 bn) is allocated towards a longer-term recovery plan including investments in broadband, as well as skills training and job support which should support growth potential over the medium term. Tax relief measures, as well as electricity cost support, should alleviate cost pressures for businesses during the recovery, but the permanent nature of the measures adds to structural deficits without offsetting revenue measures.

The government has bought time by using the escape clause in its balanced budget legislation. However, it has committed to laying out a path to balance in its next budget expected this winter. They may very well be banking on good luck (with stronger economic and revenue outcomes) or good will (with sizable, multi-year increases in federal transfers). Otherwise, the government may need to dust off some of its expenditure restraint plans it had launched prior to COVID-19. Post-pandemic, this will be all the more challenging as many social costs are expected to remain elevated, while significant increases in new Canadians in outer years—while boosting growth—will also pressure social infrastructure.

A STEEP ECONOMIC RETRENCHMENT WITH SOME UPSIDE

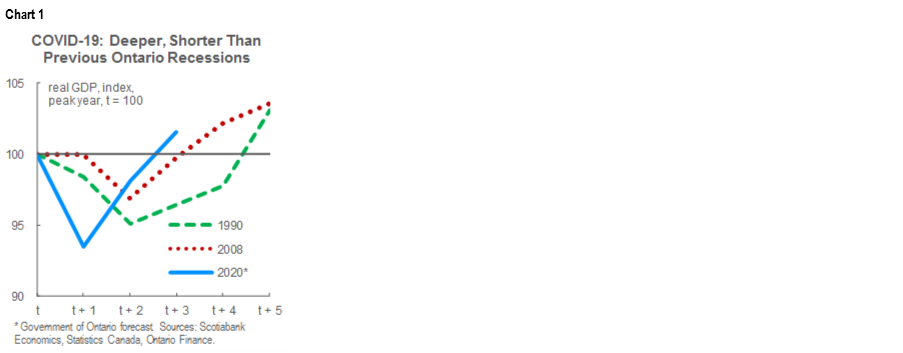

Ontario’s economic outlook was largely unchanged from the August update. COVID-19 has resulted in severe economic contractions around the globe, and Ontario continues to expect to witness a record real GDP decline in excess of 6% this calendar year. A range of economic indicators—from employment to housing purchases to merchandise exports—have recovered strongly since reopenings from first wave lockdowns began. The Province continues to base its planning assumptions on economic growth more modest than the average among private-sector forecasters through 2023. Even under that more conservative set of assumptions, however, the province would recoup its losses by 2022, representing a short recovery period relative to those in past downturns (chart 1).

Noting the high degree of uncertainty to the evolution of the virus and the economic outlook at this juncture, the province outlined three scenarios. The base case underpins the current deficit projections. A higher-growth scenario over calendar years 2021–23 is associated with real GDP 2.3% higher than the base case in the final year, and an FY23 fiscal shortfall of just $21.3 bn. A lower-growth situation in which real GDP is 4.5% lower than the base case results in a deficit of more than $33 bn in FY23. In this scenario, Ontario output would not reach its pre-pandemic level during the forecast horizon. Our own forecasts at Scotiabank Economics are slightly more optimistic with respect to the 2020 downturn, envision a real GDP contraction of almost a percentage point less than the budget’s baseline scenario.

FISCAL SPENDING TO SUPPORT THE RECOVERY

Ontario expects to run a deficit in FY21 in line with earlier forecasts at $38.5 bn or 4.5% of GDP (chart 2). Total COVID-19 spending now amounts to $45 bn over three years, including an additional $15 bn allocated in this budget. Over $8 bn in the FY21 deficit forecast is held against contingencies. The outstanding balance for COVID-19 contingencies stands at $2.6 bn, a general continency at $3 bn, and a reserve at $2.5 bn. The government has committed to offsetting debt if these amounts are not required.

Government revenues will take an expected hit as a result of the economic contraction. Notably, corporate tax revenues will drop by an exceptional 35% y/y, while sales tax revenues will dip by 13% y/y. Personal income tax receipt declines are more modest—at -2% y/y—which may have some upside as employment benefits are taxable. Aggregate government transfers have exceeded lost wages with a consequent uptick in personal disposable income expected this year. This represents an upside for revenues. Overall, government taxation revenues are expected to decline by 10% in FY21, but with other non-tax revenues including federal transfers, the decline is more modest at 3%.

Pandemic spending is driving expenditures higher. Total expenditures in FY21 will jump by a sizable 13.5% y/y (chart 3); after netting out COVID-19 spending, the increase is still significant at almost 9% y/y as other social systems are pressurized. While COVID-19 spending is expected to decline in outer years, the budget builds in additional pandemic-related contingencies of $6 bn between FY22–23, while broader health care spending is also expected to remain elevated. Consequently, expenditures are expected to decline by 2% in FY22 but pick up in FY23. Expenditures at the end of the budget horizon will stand 13% above pre-pandemic levels in FY20.

Federal government transfers remain the wildcard. The province has pencilled in a $7 bn boost in additional federal transfers already announced for FY21 (mostly through the Safe Restart agreement). With the bulk of pandemic-related healthcare costs falling on provinces in the near-term and key federal policy priorities falling under provincial mandates, it is not unreasonable to expect further—albeit targeted—support to provinces. The budget repeats an earlier plea to increase the federal share of health care costs to 35%, which would amount to an additional $9 bn in transfers for Ontario alone in FY21.

MODEST CONSOLIDATION ON THE HORIZON (FOR NOW)

The province anticipates modestly declining deficits over the budget horizon. Projected deficits for FY22 and FY23 are -$33.1 bn (3.6% of GDP) and -$28.2 bn (2.9% of GDP), respectively. This relatively cautious pace of consolidation—with a contraction averaging about 0.8% of GDP per year—is slightly faster than previous recessions which saw deficits contracting by about half a percentage point each year following the crisis. With the government expecting GDP levels to only reach pre-pandemic levels in 2022, this suggests excess capacity will persist through 2023, with unemployment, for example, to still forecast to be elevated at 6.3% by 2023. The pace of consolidation is broadly calibrated to this baseline scenario, and should not risk stalling the recovery, particularly when coupled with ample federal fiscal support.

On the other hand, conservative forecasting and ample contingencies and reserves built into the outlook suggest consolidation could proceed more quickly. In its optimistic growth scenario, deficit spending would be approximately 2.2% of GDP by FY23 with a contraction of over 1% of GDP each year in that period. This would also bring it close to recent estimates by the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario which recently projected a deficit of 1.7% of GDP by FY23 (before new spending announced in this budget).

The government is using the escape clause in its balanced budget legislation…for now. It introduced the Fiscal Sustainability, Transparency and Accountability Act only in 2019, requiring details on when and how the budget will subsequently be balanced when the government runs deficits. (Recall, the government had set out a path to fiscal balance by FY24 prior to the pandemic.) Consistent with best-practice, the legislation includes an escape clause for extraordinary circumstances and the government has rightly taken advantage of this clause. There are no details in this budget with respect to balancing the budget, but the government commits to providing a path to balance in the 2021 budget expected next winter.

DEBT LEVELS TO TICK UP MODESTLY

Larger deficits will push up Ontario’s debt over the outlook. Net debt is expected to reach 47.0% of GDP in FY21 and to continue to increase modestly to 49.6% by FY23 (chart 4). This reflects an all-time—but unavoidable—high for the province. Temporary pandemic spending and projected low interest rates should moderate the increase in debt levels, but more importantly economic growth, and associated revenue recovery, have the potential to reverse the upward trend.

Importantly, net debt as a share of GDP would stabilize under the higher growth scenario laid out by the budget. Netting out various contingencies and reserves would put it on a downward trajectory. A winter budget should provide greater clarity on whether a high degree of conservatism is needed. Absent that, they may be looking to return to expenditure restraint measures laid out prior to the pandemic once the economy has fully recovered.

Nevertheless, debt remains sustainable. Rating agencies may hold off on passing judgement until further details are laid out on how the government intends to stabilize debt levels in the winter budget. Several had upgraded Ontario’s outlook prior to the pandemic based on solid fiscal management that was translating into stabilizing debt levels. With the onset of the pandemic, agencies broadly agree across sovereign and subnational assessments that temporary spending was necessary, while shifting their scrutiny to post-pandemic debt management, including the recovery of revenue-generating activities. The budget plan should provide some confidence in this regard, as revenues are expected to recovery over the horizon, while new spending is relatively well contained but agencies will likely be looking for the path to stabilizing levels.

MARKET DEMAND ROBUST

Borrowing activity is expected to total $170 bn between FY21 and FY23. This includes a small increase of $200 mn in FY21 versus August forecasts. About two-thirds of funding activity for this year had already been completed by mid-October. About 79% of fiscal year-to-date borrowing has been in Canadian dollars, in line with the Province’s 70–80% target. Ontario remains the largest issuer of Green Bonds in Canada, having issued its eighth and largest Green Bond to date as of early October.

Ramped-up capital spending will contribute to financing requirements. The FY21–23 Capital Plan invests $45 bn in the province, with a sizable amount dedicated towards transit, highways, schools, hospitals and broadband. While these will add to gross market debt levels, they reflect an important re-investment in productivity and should leverage private investment at a critical time when the pandemic is expected to erode capital stock. (The budget also urges the federal government to step up its own share of funding for Greater Toronto Area subway investments, as well as an overall increase in federal infrastructure outlays of $10 bn per year over the next ten years for ‘shovel-ready’ projects.)

Market demand should remain strong and liquid. Ontario continues to offer yield pick-up in a global bond markets increasingly dominated by negative-yielding products. Growth enhancing investments announced today should underpin its relative attractiveness in terms of its medium-term recovery and yield implications. Its spreads relative to risk-free Government of Canada bonds also continue to remain tight. While the Bank of Canada purchase facilities provide a backstop to liquidity, this has not been needed at scales originally envisioned with interventions tapering in recent months.

Its stable outlook is supporting activity to term out more of its debt as short term liquidity needs abate. While average debt maturity is high relative to feds (10.7 years versus 6.7 years), it is still among the lowest across provinces. As governments at all levels begin looking ahead to longer term debt management strategies, locking in low interest rates is increasingly attractive. An uncertain global environment, meanwhile, supports demand in longer bonds (along with some expectation that some central banks such as the Bank of Canada will increasingly participate in this space). Ontario is well-positioned to take advantage of this in line with its stated intentions.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.