MANAGING THE VIRUS’ IMPACTS WITH PRUDENT FISCAL ANCHORS

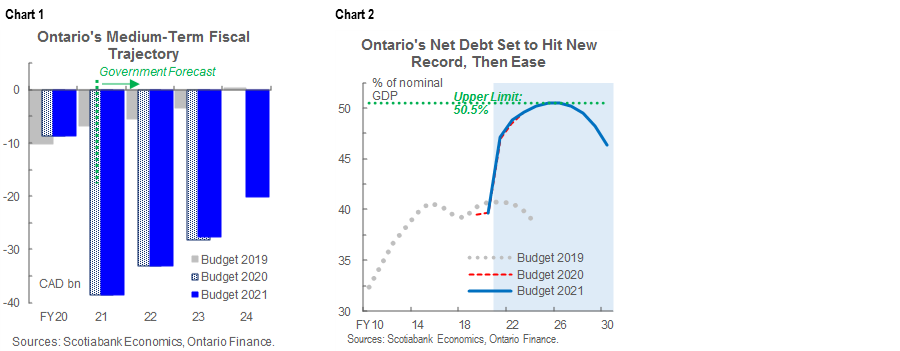

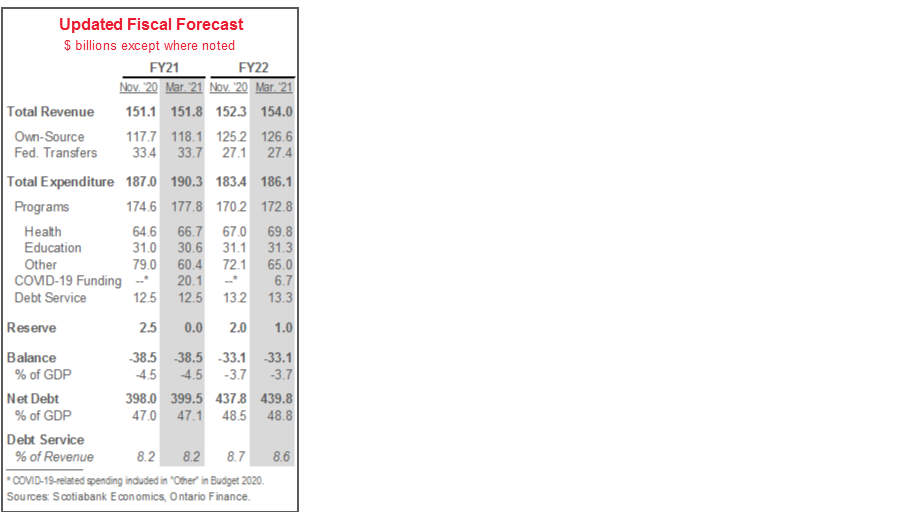

Budget balance forecasts: -$38.5 bn (-4.5% of nominal GDP) in FY21, -$33.1 bn (-3.7%) in FY22, -$27.7 bn (-2.9%) in FY23, -$20.2 bn (-2%) in FY24 (chart 1), all in line with Budget 2020 assumptions.

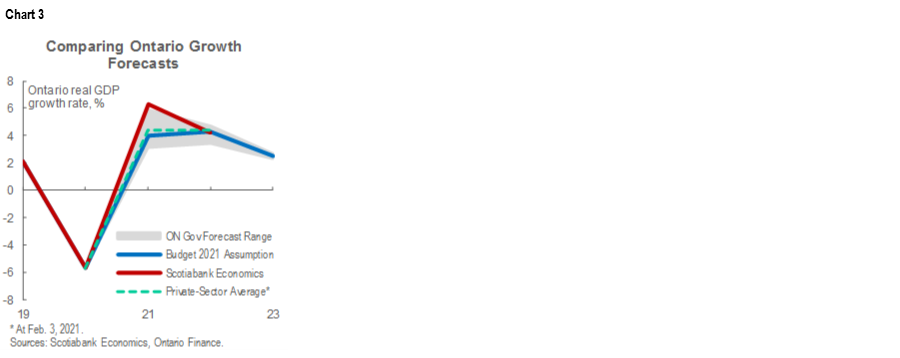

Net debt: expected to rise gradually from 47.1% in FY21 to 50.5% in FY25 and FY26, before easing in each successive year to reach 46.4% in FY30 (chart 2). The 50.5% would be the highest since at least FY87.

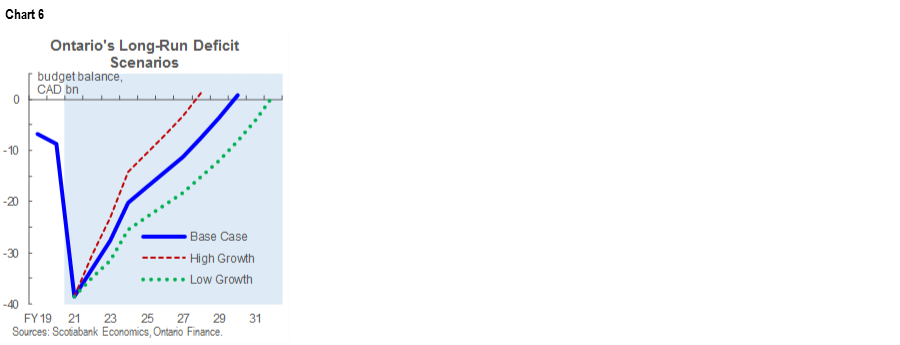

Fiscal anchors: base case forecast assumes return to balance in FY30, pledges to keep net debt-to-GDP ratio below 50.5%, reduce rate of increase in debt service-to-revenue and net debt-to-revenue ratios.

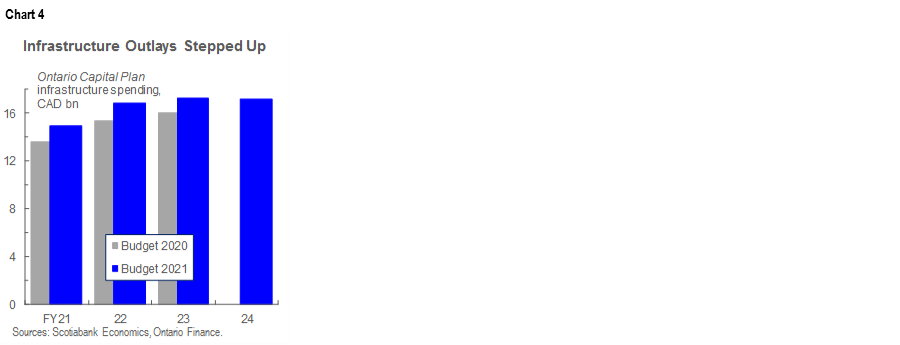

GDP growth forecast: +4% in 2021 and +4.3% in 2022, +2.5% in 2023, which puts the provincial economy on track to reach to its pre-pandemic level in calendar year 2022.

Borrowing program: total long-term public borrowing of $59 bn in FY21, $54.7 bn in FY22, $59.1 bn in FY23, and $55.2 bn in FY24.

We assess Budget to be a prudent plan that cushions against COVID-19 risks, leaves room for near-term upside, and sets Ontario on a path to long-run fiscal sustainability once the pandemic has passed.

OUR TAKE

We begin by emphasizing that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted Ontario’s finances just as it has most jurisdictions around the world. Before COVID-19 reached Canadian shores, a return to black ink in Canada’s largest province was not expected until FY24. The government now anticipates that that will take at least another four years, and continues to assume that it will hit record debt and deficit levels within the forecast window.

Yet this is a conservative fiscal plan that leaves real possibility of upside for near-term budget balances. Time-limited funding to protect people and jobs is estimated at $6.7 bn in FY22 and $2.8 bn in FY23; those amounts are booked as expenses and accompanied by typical forecast reserves of $1 bn in FY22 and $1.5 bn in each year thereafter. The plan is also built on economic growth below the average of private-sector projections (chart 3, p.2), some of which date from before the recent announcement of additional US fiscal stimulus. Sensitivities in the budget link 1 ppt in nominal GDP growth with $1.1 bn in tax revenues; based on that estimate, our latest 2021 forecast of over 9% growth in Ontario nominal GDP would mean another $3 bn in government receipts in FY22.

New policy measures appear appropriately targeted. Various long-term care supports aim to bolster the health system’s response to the third wave and address capacity, staffing, and care delivery challenges identified during the pandemic. Funds for vaccine distribution and domestic production should help expedite inoculation and reopening this year. Further reductions in small business taxes may encourage new investment alongside further containment of COVID-19, and supports for tourism operators acknowledge the sector’s disproportionate pandemic hit. Tax credits for job retraining and additional payments under the Ontario Child Benefit respectively seek to mitigate the effects of post-pandemic labour market scarring and help labour market participation among parents.

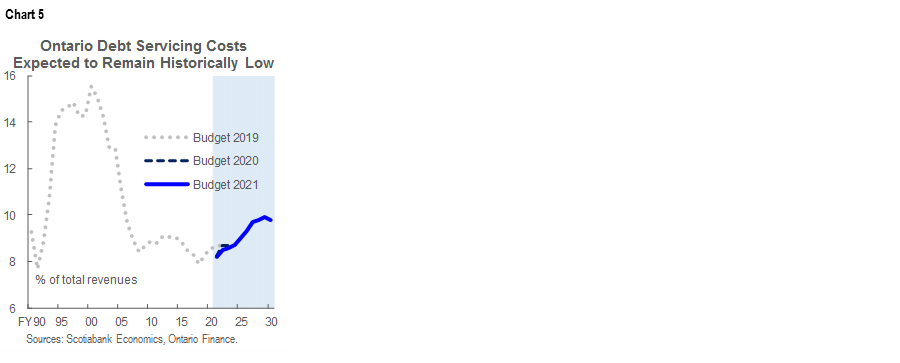

Stepped-up Infrastructure spending should also support the recovery. Total outlays scheduled under the Ontario Capital Plan were increased by $4 bn over FY21–23 versus the November 2020 Budget (chart 4, p.3). Municipal public transit remains a key plank of the Plan, and a total of $4 bn is expected to be allotted to broadband internet infrastructure during the six years beginning in FY20.

Planning anchors look appropriate. The 50.5% upper limit on the net debt-to-GDP ratio—while technically a record high—should signal longer-run discipline to creditors and also leave room to bolster the recovery and address unexpected costs should they arise. Debt servicing costs are expected to rise gradually to nearly 10% of revenue over time—a natural consequence of the shift in interest rates and inflation expectations over the last several months—which would keep them low relative to history (chart 5, p.3). The province will also monitor net debt’s share of revenue; it expects this indicator to peak in FY26 alongside the net debt-to-GDP ratio. For the latter two indicators, the province’s stated objective is to reduce the rate of increase, supported by GDP growth.

Federal transfers and spending plans continue to mirror expectations about the pandemic’s trajectory. Like last year’s budget, this plan assumes that funds earmarked by Ottawa for pandemic relief will draw down by about $7 bn in FY22. By the same token, pandemic-related contingencies—registered within the plan as expenses—will completely wind down by FY24. Excluding those amounts, the province expects program spending to rise by more than 5% this year and more than 2% next year, then slow in FY24. Over the longer-run, program spending is assumed to advance by an average of about 2% per annum.

Total long-term public borrowing is forecast to total $59 bn in FY21, $54.7 bn in FY22, $59.1 bn in FY23, and $55.2 bn in FY24. For FY22 and FY23, those figures represent reductions of $3.9 bn and $0.2 bn, respectively, versus 2020 Budget projections. The province noted that at the time of publication, some 65% of FY21 borrowing had been completed in Canadian dollars, a portion lower than the 70–80% range typically targeted because of increased global demand for Ontario debt. To achieve a 6–8% share of total debt outstanding, short-term borrowing will be increased by $6 bn in FY22 and a further $2 bn in FY23. The average term of Ontario’s debt portfolio is 10.7 years, a level the province intends to maintain. Multiple Green Bond issues are planned for this year subject to market conditions.

The decision to include long-term fiscal forecasts and scenarios adds to the transparency and credibility of the plan while also acknowledging the elevated level of uncertainty in the outlook at this time. The base case fiscal forecast is associated with a return to black ink in FY30. Under the stronger economic growth scenario, balance would occur two years earlier; weaker growth would delay surplus until FY32 (chart 6, p.3). The province similarly projects that a stronger-than-anticipated expansion would result in borrowing requirements about $3 bn lower than under the baseline in FY22, $4.4 bn lower in FY23, and $6 bn lower in FY24. For net debt, the softer growth scenario would result in a 52% share of nominal GDP in FY24; a faster expansion would mean a peak 48% share in FY23.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.