GDP growth doubled the BoC’s expectations in Q4…

...and preliminary tracking continues to exceed BoC expectations

Spare capacity is closing fast

Inventories stabilized in Q4 after prior drawdowns…

...and are likely to be a supportive influence to this recovery

The economy continued growing during December and January, despite lockdowns and restrictions

Biden’s stimulus will make Canada great again…

…as Canada’s Spring budget risks overheating

CDN GDP, m/m Dec // q/q Q4 SAAR, %:

Actual: 0.1 / 9.6

Scotia: 0.3 / 7.6

Consensus: 0.1 / 7.3

Prior: 0.7 / 40.5

January preliminary guidance: +0.5 m/m

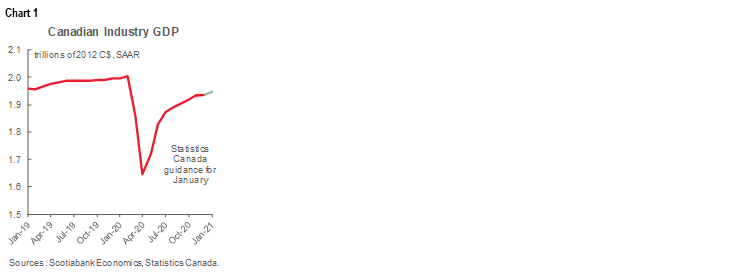

Canada’s economy is tracking GDP growth at a pace that is so far six times faster than the Bank of Canada’s annualized forecasts for 2020Q4 and 2021Q1. Including January’s guidance, the level of GDP has now recovered to over 97% of where it was back in February before the pandemic struck and dragged the economy about 18% lower over the span of just two months in March and April (chart 1). The economy remains on track to close spare capacity much sooner than the Bank of Canada has projected which is in keeping with our expectations for earlier rate hikes than the BoC’s 2023 guidance indicates. That probably points toward a coming narrative reset in the BoC’s April MPR.

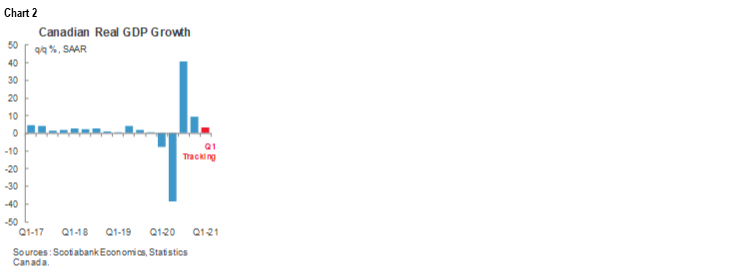

GDP growth smashed expectations and the BoC’s forecasts which is the point of comparison because of the policy implications. Growth landed at 9.6% q/q at a seasonally adjusted and annualized rate in Q4. Early tracking for Q1 points to 3.3% annualized growth (chart 2). Compare that to the BoC’s January forecast that predicted growth of 4.8% in Q4 followed by a -2.5% annualized contraction. The GDP profile that stems from 9.6% followed by 3.3% compared to the BoC’s forecasts for those same quarters has growth tracking a cumulative annualized 6.4% rate over the half year versus the BoC’s 1.1% projection. That’s a forecast beat of six times the anticipated rate of growth. Major upward forecast revisions are ahead at the BoC and will be present in the April MPR with possible statement guidance next week.

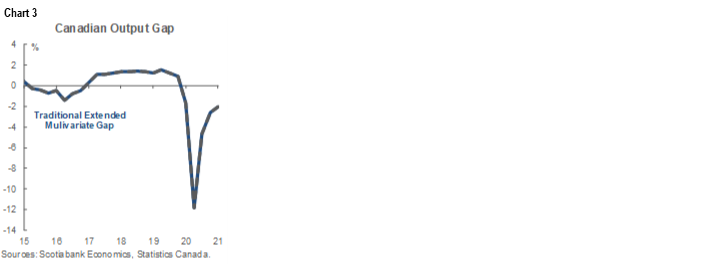

What it means is that the traditional measure of the output gap is probably around –2% now in Q1 (chart 3). That’s ten percentage points of less slack than was the case back in Q2 of last year as the economy shut down. I’ve used the mid-point of the BoC’s estimates for potential growth and married them to the pattern to date in actual GDP growth and preliminary Q1 tracking. If vaccines combine with imported benefits of massive US fiscal stimulus and further fiscal stimulus in Ottawa’s Spring budget then we could very easily shut spare capacity this year—maybe even by summertime—and begin edging into excess aggregate demand. For a central bank so wedded to its output gap framework and how it connects to inflation forecasts, it is going to be increasingly difficult for it to credibly say that we’ll have spare capacity for another three years yet and to do so with a straight face. They should be altering the narrative as the stimulus put in place almost a year-ago was set for a very different world than the one we’ve transitioned toward.

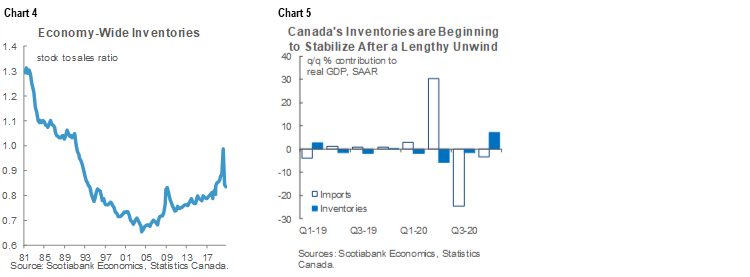

Inventories contributed seven of the 9.6 percentage points of GDP growth in Q4. That is not a bad thing and be careful with some of the numbers you may have seen. In fact, it’s a very constructive development to the outlook and it requires some context. Inventories were massively depleted through the first three quarters of this year and then posted a very small rise of just C$1.7 billion in Q4. Because they were up by just C$1.7 billion in Q4 but the prior quarter was down by C$36.8 billion, the GDP math drove inventories to contribute a large share of the GDP gain even though they barely changed in the final quarter.

I would expect a lot more of a focus upon a desired inventory build as the recovery proceeds. Witness yesterday’s US ISM-manufacturing report including the sector anecdotes. The aggregate economy-wide inventory-to-sales ratio has declined from the peak in the second quarter of last year when sales tanked (chart 4). As growth continues to accelerate in our forecasts, either restocking will need to occur or the inventory-to-sales ratio is going to get back to extremely lean levels. This is to be expected as supply chains recover from the pandemic’s hit and the earlier hits from Trump’s trade wars. Chart 5 shows that inventory depletion had become the norm in Canada for several quarters until the Q4 contribution to growth that provided an exaggerated sense of the modest dollar swing.

Inventories cannot be divorced from imports in an open economy like Canada’s. Imports were up in Q4 by enough to shave 3.3 points off of annualized GDP growth. As inventories stabilize, they will tend to coincide with less of a draw down in imports and a shift toward outright higher imports. Therefore as supply chains recover, it’s important to take the inventory contribution net of the import subtraction for an overall net contribution of 3.9 percentage points to GDP growth out of the overall 9.6 percentage point GDP growth rate.

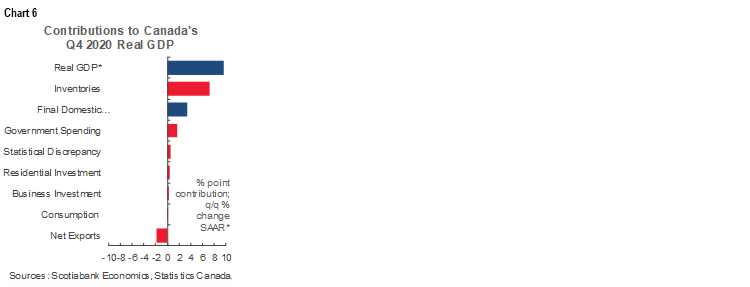

Chart 6 shows the weighted contributions to GDP growth by category. Consumer spending was a drag of about 0.26 percentage points off of GDP growth which isn’t really new information given tracking and the effects of lockdowns and restrictions. Government spending added 0.29 points. Housing contributed 1.6 ppts to GDP growth while business investment added 0.3 points entirely through higher equipment spending as investment in nonresidential structures fell. Export growth added 1.5 ppts and the decline in imports acted as less of a leakage on GDP so it added 3.3 ppts to GDP growth.

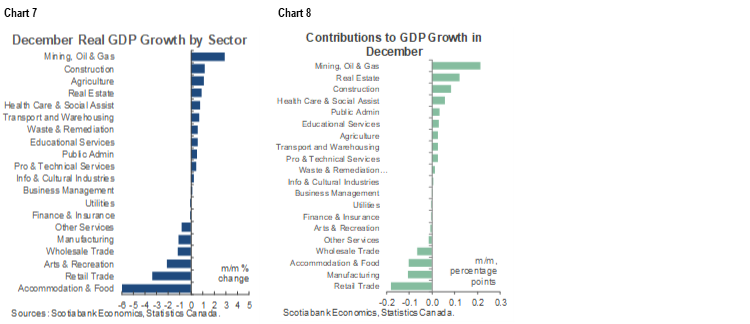

Chart 7 shows the break down of the 0.1% GDP growth by sector during December. Chart 8 does the same thing but in weighted terms to overall GDP growth that makes it clearer which sectors did the heavy lifting.

StatsCan’s preliminary guidance for January points to a 0.5% m/m gain but the flash estimate does not share details beyond general guidance that wholesale, manufacturing and construction led the way. That’s frankly amazing during tightened restrictions.

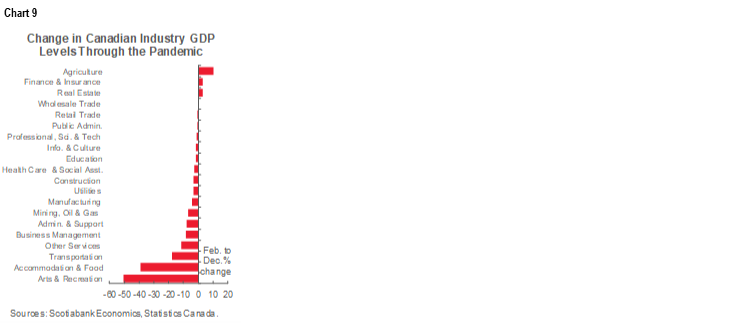

Chart 9 makes is clear that with the exception of a handful of sectors, much of the economy is clawing its way back toward February GDP levels. The few sectors that are behind the most are clearly the ones that have been hit hardest by the pandemic. They are also the ones with potentially the most to gain should behaviour start to respond favourably to vaccinations over 2021 into 2022.

Now clearly this kind of momentum has to continue in order for the Bank of Canada to get to tightening monetary policy. I think it could very well do so. The US Biden administration’s massive fiscal stimulus that adds a dozen points of nominal GDP in just two bills spread about three months apart from one another will likely partially leak out into demand for Canadian exports. If the Biden administration then adds another infrastructure bill later this year that uses the budget reconciliation method then further imported stimulus effects into Canada could be felt. Add to that C$70–$100 billion of Canadian federal stimulus in a Spring budget all on the cusp of inoculation of the US population by summer with Canada to follow and we are staring down the barrel of a very powerful set of growth drivers.

The massive stimulus that the BoC put in place almost a year ago was helpful and set in the context of a devastating shock sans vaccines and set against the prevailing narrative that fiscal policy had routinely underwhelmed in scope and sustainability. That stimulus also seriously underestimated what the vast majority who kept their jobs would do with very low interest rates, witness this morning’s home sales report out of Vancouver that was already among the world’s very priciest.

Strike out those assumptions and now the massive monetary stimulus is looking a tad out of place in a forward-looking sense. My view is that the next steps toward curtailing monetary policy stimulus should arrive as soon as next week if not in the April MPR that revisits all forecasts. Ending the Provincial Bond Purchase Program on the May timeline is a strong possibility and provinces gave a free pass to do so with front-loaded issuance. Curtailing GoC bond purchases by at least C$1B per week—if not more—is another. If the purchase program ends before the output gap shuts as Governor Macklem has been guiding, then that points toward its conclusion over the coming year. That, in turn, paves the way for getting away from an emergency policy rate setting as the emergency is rapidly passing.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.