- The federal government has been issuing unprecedented securities to finance the response to COVID-19. Gross issuance last year (FY21) tallied $593 bn—or over 50% of total outstanding market debt. Borrowing activity for FY22 is expected remain elevated at a planned $523 bn.

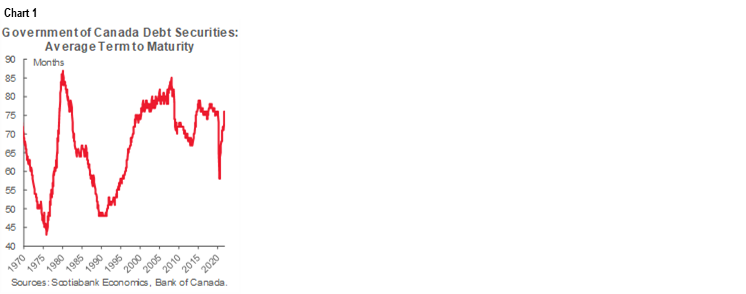

- An initial focus on the issuance of short-term securities in the interest of liquidity and expediency had sent the average maturity of debt stock plunging, but concerted efforts to lengthen issuance have since seen a recovery in duration—and a reduction in rollover risk (chart 1).

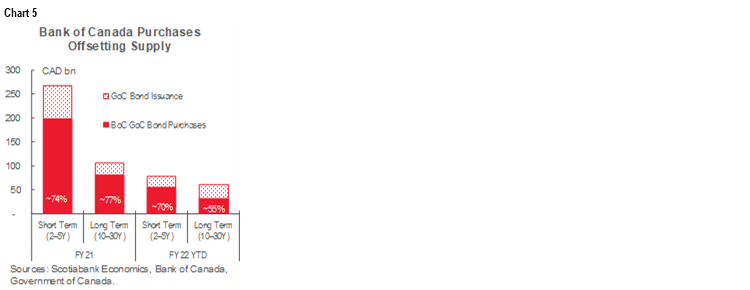

- The Bank of Canada interventions have so far lent a hand in this regard, netting out over 70% of total GoC bond issuances to-date. By the Bank’s own initial estimates, this has depressed yields by about 10 bps—and more so at the shorter end—pushing demand further out the curve.

- The government aims to continue terming out more debt as historically large volumes will mature over the next two years against still-elevated deficits. The Bank’s gradual exit introduces a degree of uncertainty around demand at the longer end but, in reality, global factors will likely continue to drive this end of the curve.

- Run-away debt levels are not necessarily the driver for action, as much as exogenous spillovers from potential US policy mis-steps and, in turn, the impact on provinces whose funding costs are inextricably linked to federal premiums (and more generally the pricing of other assets).

- Rather than asking how much demand exists, the government might ask how much it is ready to pay to hedge against an unusually wide range of potential rate paths over the near- to medium-term.

REFRESHING CANADA’S DEBT MANAGEMENT STRATEGY

The Government of Canada launched its annual debt management consultations in late September. The Bank of Canada as the fiscal agent for the federal government, has invited input from government securities distributors, institutional investors, and other interested parties on Canada’s domestic debt program for fiscal year 2023 (ending March 31, 2023).* Views would inform Canada’s annual strategy that is typically set out in a winter budget.

The objective of the debt management strategy is to raise stable, low-cost funding to meet the financial needs of the Government of Canada. It aims to balance costs and risks associated with the debt structure against evolving economic conditions. The strategy is also tasked with promoting a well-functioning market for Government of Canada securities. The Bank of Canada, as the fiscal agent, conducts debt management operations and provides strategic advice to the Finance Minister, who is ultimately responsible for the strategy.

INTEREST RATES MATTER

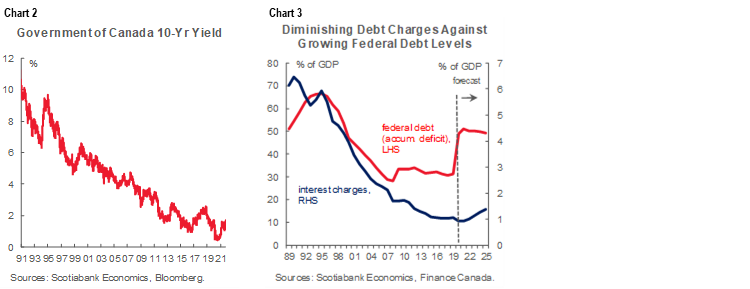

The debt strategy clearly has financial implications. The Government of Canada’s outstanding market debt stood at $1.1 tn at the end of FY21. Despite taking on almost another $400 bn in debt last year, interest charges actually declined as rates plummeted. The 10-year GoC bond yield, for example, dipped by about 100 bps at the onset of the pandemic as government responses kicked in (chart 2). Interest rates are now approaching pre-pandemic levels with still-more upward pressure ahead, but debt charges should still remain low by historical standards (chart 3).

That is the base case scenario… the interest rate outlook is currently subject to extraordinary uncertainty. Structural factors—like globalization, digitalization, and aging demographics—suggest neutral rates are lower than in the past, which would put a ceiling on the medium-term outlook for interest rates. But pandemic factors raise risks there could be more upside risk to rate outlooks than suggested by historical patterns. A higher tolerance for overshooting inflation targets, some degree of production re-shoring, and the potential for disruptive market movements around the withdrawal of quantitative easing in the years ahead all suggest the margins of error around interest rate outlooks are wider than usual.

Higher rates would push up debt servicing costs. The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) estimates that a 100-basis point sustained interest rate shock would increase public debt charges by $4.5 bn in the first year, building to an incremental $12.8 bn by the fifth year. Sensitivities are greater now that the stock of debt is markedly higher than pre-pandemic levels. There is an (unintended) automatic stabilizer against rising rates as lower actuarial amounts for some outstanding liabilities largely negate public debt charges, however it would be a false sense of security to lean on this. Even if the impacts on borrowing needs are largely neutral, it is the trajectory of debt servicing costs that concerns rating agencies (not to mention the political cost of a higher share of tax dollars servicing debt obligations).

GOING LONG

A key tool to hedge against rising interest rates (apart from borrowing less!) is to term out more debt. Namely, a government can actively extend the maturity profile of its debt stock when interest rates are low to avoid the risk of rolling over debt in less-favourable market conditions. Over the past two decades, the Canadian federal government has taken a variety of approaches to managing this rollover risk from targeting a fixed-rate share (i.e., maturities over a year) of debt stock to focusing on short- to mid-duration bond issuances.

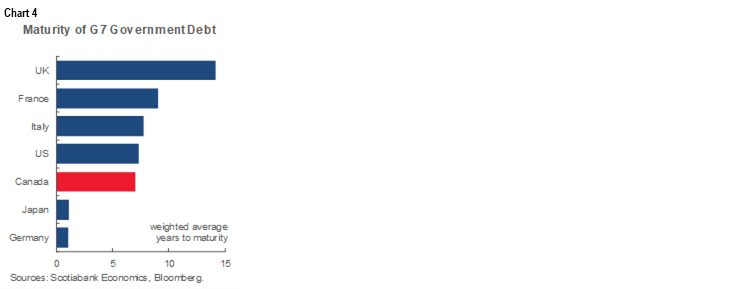

The federal government has generally been effective at delivering against plan. A series of targets between 1990 and 2005 saw the average term to maturity decisively lengthen over that period (again, chart 1). It relaxed targets just prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), while subsequent short-end emergency financing further eroded the average duration. Renewed efforts to lengthen maturities began again in 2011 with some effect. Canada’s profile relative to peers is mediocre at best, but likely more vulnerable when taking into consideration that it is a small, open economy that does not benefit from reserve-currency status (chart 4).

DOUBLING DOWN AGAIN

The pandemic saw the average maturity plunge again as emergency financing initially focused on liquidity and expediency. Treasury bills, along with short-bond sectors, carried the majority of financing needs in the first half of FY21 as the government focused primarily on getting funds out the door quickly. Consequently, the average term to maturity of the debt stock dipped briefly to a 25-year low in the summer of 2020.

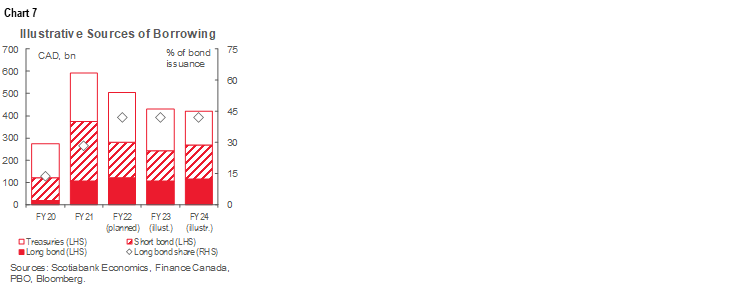

The government has nevertheless so far delivered against plan on extending the duration of its debt stock. It back-ended longer issuances (defined as 10 years or longer) last year, landing roughly on its soft issuance target set out in the FY21 debt management strategy. Long bond issuance as a share of total bond issuance surged from 14% in FY20 to 29% in FY21 (or $17 bn to $106 bn)—which effectively lengthened debt duration by over a year (to 71 months) by the end of the year. Its FY22 debt management strategy laid out a plan to further increase the long-share to 42% of total bond issuance ($120 bn). As of September, the average maturity is back to its pre-pandemic level at 76 months.

Central bank actions have given a lift to these efforts. Since the onset of the pandemic, net supply of bonds to markets has been far smaller as a result of the Bank’s Government Bond Purchase Program (GBPP), along with its primary auction purchases, absorbing about three-quarters of issuance (chart 5). As of mid-October, the Bank held $421 bn in GoC bonds on its balance sheet—a $343 bn increase over its pre-pandemic assets—whereas total issuance over this same period amounts to $511 bn. It currently holds about 42% of Government of Canada bonds (with an outstanding stock of $972 bn).

The impact has been variable across the curve. In particular, Bank purchases as a share of issuance by sector have been more pronounced in the shorter end. A recent Bank study found that the announcement of the GBPP initially lowered GoC bond yields by an average of 10 basis points, concentrated on shorter maturities, which likely would have pushed some demand to the long end in a search for yield environment, but the cumulative effects are much more uncertain.

A WINDOW TO SHIFT OUT FURTHER

Current debt management consultations tilt the hand on the government’s intent (or at least aspiration) to continue lengthening debt maturities. It seeks views on “the minimum benchmark size [for bonds] that would maintain a well-functioning market in each sector” and, more to the point, “if long-sector bond issuance was maintained at current levels, which sectors in the short end of the curve could absorb the reduction in gross issuance”. Budget 2021 had already hinted in this direction, with a passing reference that the average term to maturity is expected to increase to nearly 8 years over three years even though the debt management strategy, by practice, only provides a one-year sight line on borrowing plans.

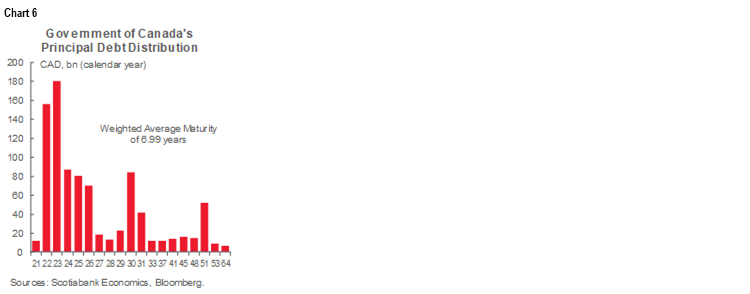

The government is appropriately aiming to capitalize on a limited window to materially move the dial further. Elevated pandemic financing needs, along with an initial predominance of short-end issuances, has translated into a mountain of debt maturing in FY23 and FY24 (chart 6). Bloomberg data places the tally at almost $340 bn over the next two years. Still-elevated deficit spending would add to government borrowing activity over this horizon. Using the PBO’s pre-election fiscal baseline and adding spending commitments from the Liberals’ election platform, total borrowing requirements in FY23 and FY24 could amount to around $445 bn and $435 bn, respectively. Framed another way, the government could reasonably be looking at annual borrowing levels that are about a third the size of the stock of debt over the next two years.

Commensurate efforts to lengthen maturities in the forthcoming debt management strategy (and the one after) would push average maturities towards the 8-year mark. A strategy that targets a similar long-sector share (e.g., 42% as in FY22) would be only modestly slower than one that targets commensurate volumes so may not be materially different from a fiscal risk perspective but would have sectoral implications. Even though the government scaled back its 30-year issuance plans last week disproportionate to projected financing requirements, it would be premature to suggest the government has cold feet in a rising interest rate environment. Given its practice of softly targeting the ‘long-sector’, this implies potentially more activity on either side of the 30-year security, but this is an assumption to monitor. Chart 7 shows a borrowing profile that holds the share of long-bonds constant, along with a more aggressive scale-back of T-bill reliance in FY24. There are obviously many moving pieces so this is illustrative only.

A WILD CARD

These efforts would likely put upward pressure on near-term interest costs. The 10-yr GoC bond yield is already back to pre-pandemic levels, hence it would already be more costly to refinance these at the same maturities before considering additional premiums to move further out the curve. Maturing debt from pre-pandemic days (i.e., at higher interest rates) would provide only a modest offsetting effect since volumes are much smaller.

Meanwhile, the pullback in monetary interventions may also weaken relative demand at the longer end. As the Bank of Canada approaches its “reinvestment phase” (or net zero bond purchases), greater net supply to markets would—in theory at least—would push prices down (and yields up). Presumably the Bank’s estimated 10-bps compression in the short-sector would unwind to some extent, which would also remove some of the relative attractiveness of the longer end, but given the cumulative impacts of the program are unknown, there is a high degree of uncertainty on market reactions.

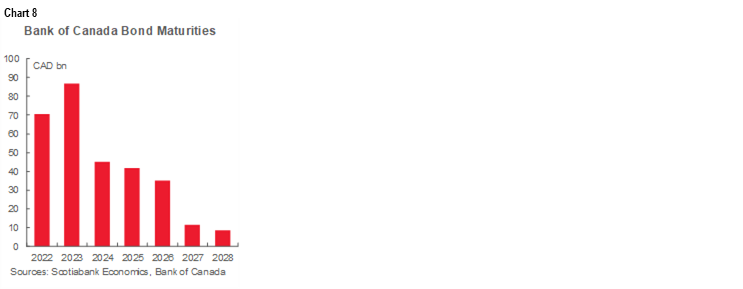

In reality, the direction and shift of Canadian bond yields at the long end will likely be driven mostly by exogenous factors. While the shorter end may be reacting to the timing of anticipated policy rate tightening, the belly is likely to be driven by distortionary central bank interventions. Even with the Bank of Canada in the reinvestment phase, it would still be netting out close to $160 bn from markets over the next two years to refinance maturing bonds on its balance sheet (chart 8). In 2023, its share would still be upward of a third of issuance. And more importantly, the US Federal Reserve has not yet reversed its accumulation of securities on its balance sheet. The effect would continue to flatten the curve as demand gets pushed out.

Needless to say, there is potential for high volatility and non-linear shifts in the rate outlook.

A CASE FOR TAKING OUT INSURANCE?

Run-away federal debt is not the biggest risk to the outlook. (That is, assuming greater spending beyond the ‘modest deficits’ laid out in the Liberal election platform is not unleashed). As noted earlier, simply capturing the sensitivity of “r” does not lead to run-away interest costs under even relatively large interest rate shocks given historically low starting points, along with actuarial offsets. Even a more sophisticated approach of measuring “r minus g” to capture the differential between interest rates and GDP growth suggests a relatively large shock (e.g., the 10-year GoC yield approaching 5%) would be required to set debt on an ‘explosive trajectory’.

Spillovers should likely be front-of-mind for the federal government. US structural deficits give it a smaller margin to maneuver before it could experience a potentially ‘explosive debt’ scenario, driving up bond yields around the world. Admittedly, this is only tail-risk, but even a modest repricing of US fiscal risk would put material pressure on the cost of financing for governments around the world. The federal government would be in a position to absorb these costs under most realistic scenarios, but provinces would be more sensitive to shocks, with considerable variability across regions. Even though provinces have done a better job collectively at extending debt maturities, their rates are inextricably linked to the federal government bond market premiums even if they are viewed by markets as distinct offerings from a demand perspective. A failure to manage term risk at the federal level could have a far bigger impact at the sub-national level—including through non-linearity—than may be fully captured in cost-risk assessments.

A key take-away for debt managers (whether within government, corporations, or even households) is to hedge against a wider range of interest rate outlooks. As for the federal government’s debt management consultations, rather than asking market participants whether sufficient demand at the longer end can continue to support efforts to term out the debt, the question might be redirected back to the government: how much of a premium should the government be willing and ready to pay to reduce term risk given its “public good” role in setting the yield curve in a highly uncertain and volatile environment?

* This note considers the issue only from a fiscal risk perspective. Scotiabank Global Banking & Markets fixed income specialists closer to institutional clients are providing thoughtful input to the federal government’s debt consultations that will capture other important market considerations.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.